Ancient Mariners of the Mediterranean

With 95 percent of the seafloor not yet explored, oceanographers and maritime archaeologists look to the deep waters of the Mediterranean and Aegean seas for shipwrecks that can be used to tell the story of ancient civilizations throughout the region.

Anthropology, Earth Science, Oceanography, Social Studies, Economics, World History

The study of oceanography brings many different fields of science together to investigate the ocean. Despite increased research and advances in technology , the depths of the ocean remain mostly unexplored. Archaeology is the study of human history using the material remains, or artifacts , of a culture. Artifacts help reveal a particular group’s culture, including their economies, politics, religions, technologies, and social structure. Maritime, or underwater, archaeologists study artifacts and sites submerged in lakes, rivers, and the ocean. While many land-based archaeological finds have already been studied, the ocean depths contain countless new sites and artifacts yet to be discovered.

As ancient people began to develop civilizations , or urban settlements with complex ways of life, extensive trade routes formed throughout the Mediterranean. The eastern Mediterranean and Aegean seas formed an important crossroads of trade and travel in the ancient world. By exploring shipwrecks from this region, researchers learn more about the people who lived there throughout history, as far back as 1000 B.C.E ., when Greek civilization was on the rise. Oceanographer Dr. Robert Ballard works with maritime archaeologists to explore ancient shipwrecks throughout the Mediterranean. By studying these ancient wrecks, the history and culture of the region’s ancient civilizations can be better understood.

Finding and excavating ancient shipwrecks in the deep o cean requires the use of advan ced technology , including sonar and ROVs . On ce wrecks are located using sonar , ROVs with cameras are used to observe them. One way to determine the historical time period the shipwreck came from is to identify key artifacts . In the ancient world of the Mediterranean region, one such key artifact is an amphora , a clay jar that was used to transport goods like olive oil, grain, and wine. By viewing video footage captured by the ROVs , expert archaeologists observe the shape and style of the amphorae to determine approximately where and when they were used. The shape of an amphora ’s base can vary from well-rounded or barrel-shaped to conical. Its neck can appear separate from the base or as one continuous pie ce . An amphora ’s handles can fall vertically or be more rounded. The stamps and designs, such as ribbing, used on amphorae indicate different regions and time periods in which the jars and their contents came.

Using archaeological evidence, including amphorae, scientists determined that most of the shipwrecks found in the Mediterranean region are from the C.E. , being no more than 2,000 years old. That makes shipwrecks like the one Ballard’s team discovered in the deep Aegean Sea such a remarkable find. Based on the ribbed, conical-shaped amphorae from the wreck, the ship was likely transporting goods to and from the Greek island of Samos during the Archaic period of Greece (seventh century B.C.E.), says archaeologist and ceramics expert Andrei Opait. This was two hundred years before the Classical period of Greece (fifth century B.C.E.), when Plato and Socrates were living and Greek maritime power dominated the region. If Opait’s theory is correct, the wreck would be the oldest ship ever discovered in the Aegean Sea. According to Ballard, this shipwreck is just one of thousands yet to be discovered in the depths of the Mediterranean.

- The average depth of the Mediterranean Sea is 3,000 meters (9,840 feet), with its deepest point at approximately 5,000 meters (16,400 feet).

- When broken down into its Greek root words, the term “archaeology” literally means “study of the ancient,” from arkhaios, meaning ancient, and logia, meaning study of.

- The excavation of the Cape Gelidonya shipwreck off the south coast of Turkey in the 1960s was an important event for the field of maritime archaeology for three main reasons: It was the first excavation where the supervising archaeologist, George Bass, both dove to and excavated a site; it was the first time where land-based archaeological techniques were adapted for the underwater environment; and it was the first shipwreck to be entirely excavated.

- The Nautilus Expedition uses state-of-the-art remote sensing and satellite communication technology to connect researchers across the globe. These technologies allow researchers at sea aboard the E/V Nautilus to send data and high-definition images to the Inner Space Center (mission control) in Rhode Island within 1.5 seconds.

Audio & Video

Media credits.

The audio, illustrations, photos, and videos are credited beneath the media asset, except for promotional images, which generally link to another page that contains the media credit. The Rights Holder for media is the person or group credited.

Last Updated

October 19, 2023

User Permissions

For information on user permissions, please read our Terms of Service. If you have questions about how to cite anything on our website in your project or classroom presentation, please contact your teacher. They will best know the preferred format. When you reach out to them, you will need the page title, URL, and the date you accessed the resource.

If a media asset is downloadable, a download button appears in the corner of the media viewer. If no button appears, you cannot download or save the media.

Text on this page is printable and can be used according to our Terms of Service .

Interactives

Any interactives on this page can only be played while you are visiting our website. You cannot download interactives.

Related Resources

- Advertise with us

- History Magazine

- History of England

Gaul To Britannia, The Crossing of Oceanus Britannicus

Sea travel in ancient times could be a dangerous business and crossing Oceanus Britannicus was particularly hazardous with its unpredictable weather conditions…

Laura McCormack

Sea travel in ancient times could be a dangerous business and travelling into unfamiliar territory and the uncertainty of what might be encountered, a perilous affair. The shores of Gaul were once considered as being at the end of the world and almost another world. Accounts of Emperor Claudius’ legions on the eve of his invasion of Britain in 43 A.D., tells of them at first flatly refusing to face a voyage to Britannia, this place outside the world with its dangers of being wrecked or castaway on a hostile shore. Although Julius Caesar in 55 B.C. had shown that an invasion across Oceanus Britannicus from Gaul was feasible, Claudius’ army may still have feared that anyone travelling that far could fall off the edge of the earth.

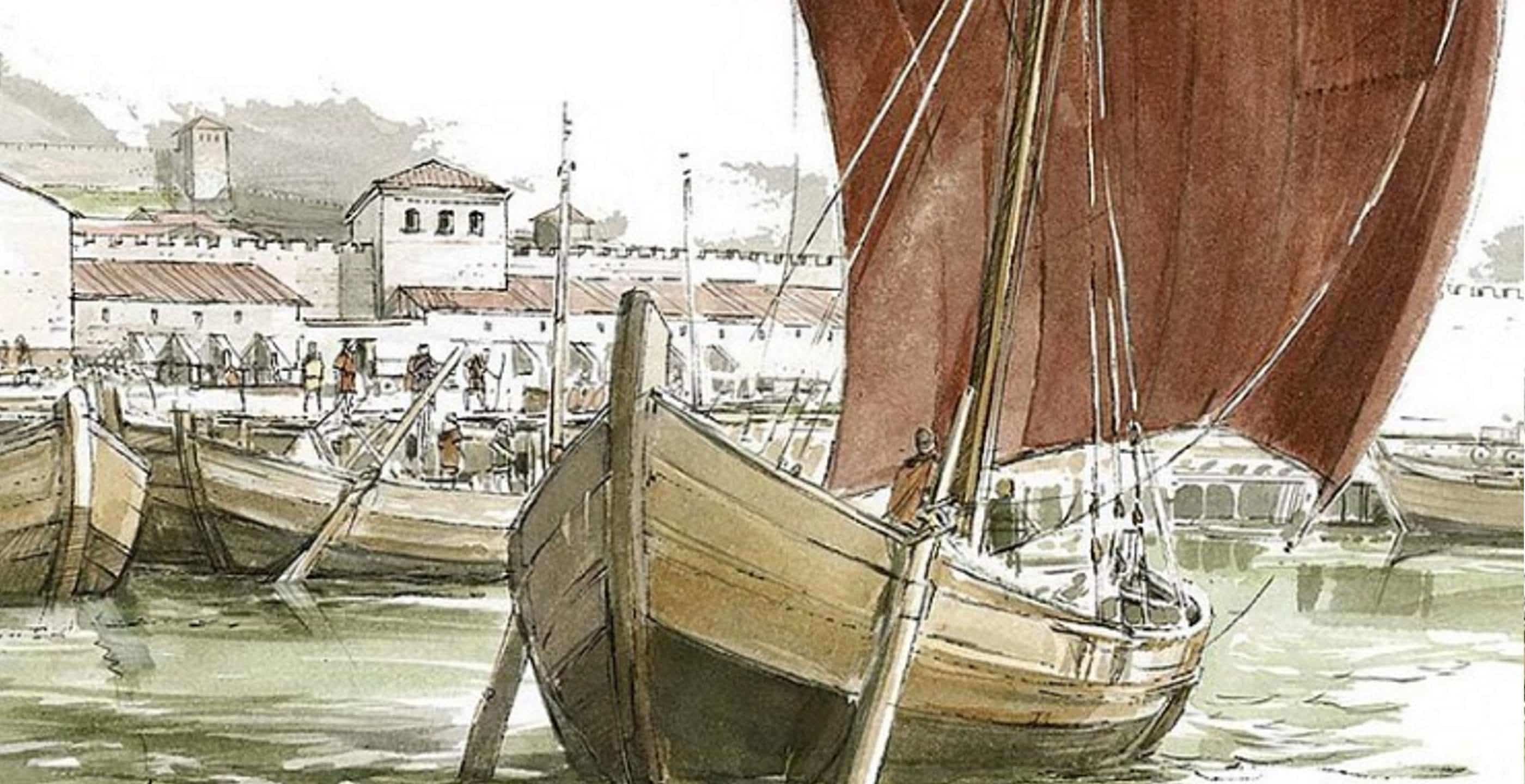

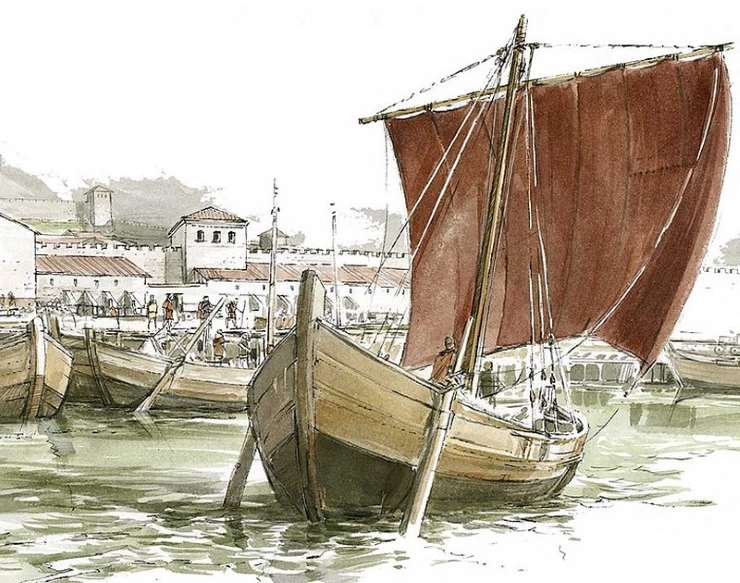

Following the conquest, Britannia became a Roman province. As a province it developed a number of ports to handle the increase in shipping, including Portus Dubris (Dover), Portus Rutupiae (Richborough), Portus Lemanis ((Lympne) and in Gaul, Gesoriacum. Gesoriacum developed around an expanding port and linked the continent to Britannia. The sea journey across Oceanus Britannicus (the English Channel) from Gesoriacum to the port of Rutupiae in Britannia (Richborough, Kent) was recorded in the Antonine Itinerary as a distance of four-hundred and fifty stadia, 56.25 Roman miles. This was the most direct route to Britannia. It is thought that three hundred and fifty stadia would be closer to the actual distance, however the need to navigate hazards in the channel could account for the the extra one hundred stadia recorded in the Itinerary. Depending on the weather, the journey across the channel to Britannia could take a ship six to eight hours.

For those travellers who were accustomed to sailing the Mediterranean, the weather conditions they could encounter on Oceanus Britannicus would be considerably more hazardous. Oceanus Britannicus was known for its precarious waters, with massive tides and currents accompanied by variable winds which could make for a difficult crossing. The channel during the winter is far more prone to violent winds than the stormiest region of the Mediterranean. Although the frequency of powerful winds blowing through the channel is greatly reduced during the summer, modern records suggest that ships sailing between Britain and the continent in July still expect to encounter strong or gale force winds on two percent of occasions. In the Mediterranean, tides are hardly perceptible in comparison to tides around the coast of Britain, which can rise and fall anywhere between 1.5 to 14 meters twice daily. Romans made ships for these harsher conditions which would withstand the tidal waters of the north western hemispere. Ships were designed with high bows and sterns to protect against heavy seas and storms. These vessels were also built flat bottomed, enabling them to ride in shallow waters and on ebb tides.

Navigation across the channel was aided by pharos. The lighthouse Tour d’Ordre at Gesoriacum and on the opposite coastline, a pair of pharos, momumental structures at a height of over twenty metres, were situated on the headland flanking either side of the major port of Dubris. The remains of one of these lighthouses survives within Dover Castle. The Romans also maintained a fleet, the Classis Britannica, present in the channel from the 1st century A.D. which provided security for crossing vessels. The fleets purpose was to transport men and supplies and patrol the channel keeping the sea routes free of pirates. The fleet with its headquarters in Gesoriacum, the major Roman naval base for the north of the Empire, also had a permanent base at Dubris (Dover) and Lemannis (Lympne).

On arrival in Gaul at the port in Gesoriacum, a traveller would find himself in the midst of a hub of activity: merchant ships and naval vessels in the harbour and the busy shipyards carrying out repairs and maintenance. Journey plans for crossing Oceanus required flexibility. There was no routine sailings and to organise his passage the traveller would set about finding the next available ship. He would also need to be aware that not only unsuitable weather conditions prevented sailings, also on ill-omened days; on dates such as the 24 August, 5th October and 8th November, no ship would leave port. Once the next available sailing was found, a deck passage would be booked with the master of the ship, the magister navis.

Ships were merchant vessels not given over to comforts for those passengers on board. There were no cabins, although sometimes small tent-like shelters were used. Before sailing, the ships authorities would always carry out the pre-sailing sacrifice to the gods of a sheep or a bull at the harbour’s temple. Larger ships might have had an altar and a sacrifice could be made on board. If the omens were not right, the sailing would be delayed, positive signs combined with good weather ensured departure. The traveller, anxious for his own personal protection, might also have appealed to Mercury, the god of safe travel. Julius Caesar wrote that Mercury was the most popular god in Gaul and Britannia. One common practice for protection was to wear a brooch depicting a cockerel, herald of each new day, which was associated with the god.

Ancient sea journeys could be uncomfortable and fearful. Once on board, the traveller might settle his nerves and occupy himself by talking with other passengers or perhaps by watching the handling of the vessel; the helmsman guiding the ship, pushing and pulling on the tiller bars or the sailors trimming the lines of the main sail and the deckhands carrying out their duties.

The journey across Oceanus Britannicus with all its possible hazards was nevertheless, a relatively short crossing. On a fine day, there would be a clear and comforting view of Britannia. Approaching the coast of this remote province, the high chalk cliffs of Dover towered, “stupendous masses of natural bulwarks,” was how they were described by one Roman general. For the traveller it must have been a very welcoming sight.

History in your inbox

Sign up for monthly updates

Advertisement

Next article.

Roman Sites in Britain

Browse our interactive map of Roman sites and remains in England, Scotland and Wales.

Popular searches

- Castle Hotels

- Coastal Cottages

- Cottages with Pools

- Kings and Queens

- Share full article

Advertisement

Supported by

On Crete, New Evidence of Very Ancient Mariners

By John Noble Wilford

- Feb. 15, 2010

Early humans, possibly even prehuman ancestors, appear to have been going to sea much longer than anyone had ever suspected.

That is the startling implication of discoveries made the last two summers on the Greek island of Crete. Stone tools found there, archaeologists say, are at least 130,000 years old, which is considered strong evidence for the earliest known seafaring in the Mediterranean and cause for rethinking the maritime capabilities of prehuman cultures.

Crete has been an island for more than five million years, meaning that the toolmakers must have arrived by boat. So this seems to push the history of Mediterranean voyaging back more than 100,000 years, specialists in Stone Age archaeology say. Previous artifact discoveries had shown people reaching Cyprus, a few other Greek islands and possibly Sardinia no earlier than 10,000 to 12,000 years ago.

The oldest established early marine travel anywhere was the sea-crossing migration of anatomically modern Homo sapiens to Australia, beginning about 60,000 years ago. There is also a suggestive trickle of evidence, notably the skeletons and artifacts on the Indonesian island of Flores, of more ancient hominids making their way by water to new habitats.

Even more intriguing, the archaeologists who found the tools on Crete noted that the style of the hand axes suggested that they could be up to 700,000 years old. That may be a stretch, they conceded, but the tools resemble artifacts from the stone technology known as Acheulean, which originated with prehuman populations in Africa.

More than 2,000 stone artifacts, including the hand axes, were collected on the southwestern shore of Crete, near the town of Plakias, by a team led by Thomas F. Strasser and Eleni Panagopoulou. She is with the Greek Ministry of Culture and he is an associate professor of art history at Providence College in Rhode Island. They were assisted by Greek and American geologists and archaeologists, including Curtis Runnels of Boston University.

Dr. Strasser described the discovery last month at a meeting of the Archaeological Institute of America . A formal report has been accepted for publication in Hesparia, the journal of the American School of Classical Studies at Athens, a supporter of the fieldwork.

The Plakias survey team went in looking for material remains of more recent artisans, nothing older than 11,000 years. Such artifacts would have been blades, spear points and arrowheads typical of Mesolithic and Neolithic periods.

“We found those, then we found the hand axes,” Dr. Strasser said last week in an interview, and that sent the team into deeper time.

“We were flummoxed,” Dr. Runnels said in an interview. “These things were just not supposed to be there.”

Word of the find is circulating among the ranks of Stone Age scholars. The few who have seen the data and some pictures most of the tools reside in Athens said they were excited and cautiously impressed. The research, if confirmed by further study, scrambles timetables of technological development and textbook accounts of human and prehuman mobility.

Ofer Bar-Yosef, an authority on Stone Age archaeology at Harvard, said the significance of the find would depend on the dating of the site. “Once the investigators provide the dates,” he said in an e-mail message, “we will have a better understanding of the importance of the discovery.”

Dr. Bar-Yosef said he had seen only a few photographs of the Cretan tools. The forms can only indicate a possible age, he said, but “handling the artifacts may provide a different impression.” And dating, he said, would tell the tale.

Dr. Runnels, who has 30 years’ experience in Stone Age research, said that an analysis by him and three geologists “left not much doubt of the age of the site, and the tools must be even older.”

The cliffs and caves above the shore, the researchers said, have been uplifted by tectonic forces where the African plate goes under and pushes up the European plate. The exposed uplifted layers represent the sequence of geologic periods that have been well studied and dated, in some cases correlated to established dates of glacial and interglacial periods of the most recent ice age. In addition, the team analyzed the layer bearing the tools and determined that the soil had been on the surface 130,000 to 190,000 years ago.

Dr. Runnels said he considered this a minimum age for the tools themselves. They include not only quartz hand axes, but also cleavers and scrapers, all of which are in the Acheulean style. The tools could have been made millenniums before they became, as it were, frozen in time in the Cretan cliffs, the archaeologists said.

Dr. Runnels suggested that the tools could be at least twice as old as the geologic layers. Dr. Strasser said they could be as much as 700,000 years old. Further explorations are planned this summer.

The 130,000-year date would put the discovery in a time when Homo sapiens had already evolved in Africa, sometime after 200,000 years ago. Their presence in Europe did not become apparent until about 50,000 years ago.

Archaeologists can only speculate about who the toolmakers were. One hundred and thirty thousand years ago, modern humans shared the world with other hominids, like Neanderthals and Homo heidelbergensis. The Acheulean culture is thought to have started with Homo erectus.

The standard hypothesis had been that Acheulean toolmakers reached Europe and Asia via the Middle East, passing mainly through what is now Turkey into the Balkans. The new finds suggest that their dispersals were not confined to land routes. They may lend credibility to proposals of migrations from Africa across the Strait of Gibraltar to Spain. Crete’s southern shore where the tools were found is 200 miles from North Africa.

“We can’t say the toolmakers came 200 miles from Libya,” Dr. Strasser said. “If you’re on a raft, that’s a long voyage, but they might have come from the European mainland by way of shorter crossings through Greek islands.”

But archaeologists and experts on early nautical history said the discovery appeared to show that these surprisingly ancient mariners had craft sturdier and more reliable than rafts. They also must have had the cognitive ability to conceive and carry out repeated water crossing over great distances in order to establish sustainable populations producing an abundance of stone artifacts.

Royal Navy Ship HMS Trent Seizes Cocaine Worth £40 Million In The Caribbean Sea

Seafarers Hospital Society Launches Pilot Project To Support Women At Sea

Hydrocell Launches The First Hydrogen-Powered Boat

Indian Port Workers Call Off Strike After Agreeing To New Wage Settlement

The History of Ships: Ancient Maritime World

The ships we come across nowadays are large, sturdy and self propelled vessels which are used to transport cargo across seas and oceans. This was not the case centuries ago, and the current ship has undergone countless centuries of development to become what it is today.

In ancient marine times, people used rafts , logs of bamboo, bundles of reeds, air filled animal skins and asphalt covered baskets to traverse small water bodies. To be precise, the first boat was a simple frame of sticks lashed together and covered expertly with sewn hides. These boats could carry large and heavy loads easily. You get to know about examples of such ancient boats among the bull boats of North American plains, the kayaks of the Inuit’s and the coracks of British islanders. Yet another ancient boat was the dugout which is a log that is hollowed out and pointed at the ends. Some of these were even as long as sixty feet. Here is a brief attempt to traverse lightly over the history of ships and how they evolved to what they are now.

The Usage of Poles and Invention of Oar

Ancient marine history makes for quite an interesting study of the strength and survival instincts of humanity at large. For instance, in ancient times, the simple oar was not in use. Instead people used their hands to paddle along in their tiny boats. They moved rafts by pushing poles against the bottom of the rivers. Slowly, using creative instincts and ingenuity, man learnt to redesign the poles by flattening them and widening it at one end, and thus the paddle was designed to be used in deeper waters. Later on, it was again ingeniously transformed to become the oar-a-paddle that is fixed on the sides of boats.

Invention of Sails

The invention of the sail was the greatest turning point in maritime history. The sails replaced the action of human muscles and sail boats could embark on longer trips with heavier loads. Earlier vessels used square sails that were best suited for sailing down wind. Fore and aft sails were devised later.

Egyptians take the credit for developing advanced sailing cargo ships. These were made by lashing together and sewing small pieces of wood. These cargo ships were used to transport great columns of stone for monument building.

Phoenicians and their Contribution

History of ships is never complete without mentioning the Phoenicians. They deserve special mention since it is highly probable that they were the pioneers of the wooden sailing vessels that were to sail the high seas centuries later. The Phoenicians fashioned out galleys from the earlier dugouts with sails and oars providing power. As the galleys grew larger, according to specifications and requirements, rowers were arranged at two levels.

These were called the biremes by the Greeks and Romans. They also built triremes that are galleys with three banks of oars.

Types of Ships in Ancient Maritime History

As marine history and along with it, the history of ships unfolds; it draws images of intrigue and amazement at the expert and diligent craftsmanship of the ancient mariners. The medieval ships were clinker built, which refers to the clenching of nail -on technique used for securing planks. The clinker design was adapted from the earlier skin boats which had to be over lapped to make it water tight.

The Irish, in the medieval ages were in possession of more advanced vessels like the Irish curragh. These had wooden frames and a hide covered wicker hull; it is speculated that these ancient ships were fitted with removable masts rigged using primitive sails.

By 1000 AD, the famed Viking Long ship was permitted a travel into the Mediterranean. These ships were wider and had a more advanced mast stepping design.

By 800 AD an alternative form of the north European ship design, the hulk came into vogue. The Utrecht ship is an example of the hulk. Its planks are flush, butted end to end and tapered in order to draw up at the sides and at the bow and stern.

I mprovements in Marine Vessels

Ships continued to develop as overseas trade became increasingly more important. By late 1100’s a straight stern post was added to ships to facilitate the hanging rudder. This aspect improved greatly the handling characteristics of a ship. The rudder permitted larger ships to be designed. It also allowed for ships with increasingly higher free boards to be built.

As years passed, in order to avoid risk of water damage, cargo was transported in large gallon barrels called tuns. The crew could now sleep on big leather bags on deck; the passenger space was termed “steerage” and this term is still in use today to refer to passenger accommodation of minimal facilities.

The British relied heavily on the nef, a term used for ships. At this point of time, ship design took a different turn – the first distinctive feature was the plank on frame construction. This allowed for much larger ships to be built. With more ships at sea, trade occurred from nearly all ports and there arose a need for a ship that could sail from anywhere to anywhere.

The carrack was designed and she was truly one of the tall ships. It has its origin in Genoa and sports the design of three Mediterranean vessels set to sail north through the Atlantic trade in the Bat of Biscay. The carrack was almost exclusively built of carvel, a type of construction that had its uses in both skin and frame built ships. In this design, the planks are fitted edge to edge rather than overlapping. In fact the carrack was the first to use the full skeletal design with planking framed on ribs the entire way to the keel.

You may also like to read-

- The Unique Tradition of Ship Burial & the Sutton Hoo Ship Burial

- Top 10 Historic Ships of All Time

Disclaimer : The information contained in this website is for general information purposes only. While we endeavour to keep the information up to date and correct, we make no representations or warranties of any kind, express or implied, about the completeness, accuracy, reliability, suitability or availability with respect to the website or the information, products, services, or related graphics contained on the website for any purpose. Any reliance you place on such information is therefore strictly at your own risk.

In no event will we be liable for any loss or damage including without limitation, indirect or consequential loss or damage, or any loss or damage whatsoever arising from loss of data or profits arising out of, or in connection with, the use of this website.

Do you have info to share with us ? Suggest a correction

Daily Maritime News, Straight To Your Inbox

Sign Up To Get Daily Newsletters

Join over 60k+ people who read our daily newsletters

By subscribing, you agree to our Privacy Policy and may receive occasional deal communications; you can unsubscribe anytime.

BE THE FIRST TO COMMENT

For marine history: would a galley under sail gain speed or stability on course by also rowing? I see historic images of both modes combined in operation, mostly for small galleys. Thanks in advance, C. Carrillo

Hello, I have discovered two saleable formulae as an internationally recognizable scientist. Both of them had ever been verified in Germany very well. One is derived for the decarbonation of soft drinks and another for a technology of dry cell driven cruisers. I would formally sell two discoveries at mere deserved prices when authentic dealers were become available in the world. My friendly inquiry with you has been if you wish to help in this mission whatsoever on timely. Thank you very much, sincere regards, Prof. Roshan Adhikari.

Minimalist. Far to much to be said

what is boat?

What sources as in researchers, libraries, museums, archives have a collected history on the ancient practices of shipping of livestock? Zeng He in the 15th century transported wild animals. There are, of course, much earlier records of Chinese exploration (2 BC, e.g.) I am interested in the care of the animals and the loading and unloading practices.

@Jimmy: This article might be helpful – https://www.marineinsight.com/types-of-ships/7-differences-between-a-ship-and-a-boat/

Evolution of ships flowchart.

It always frustrates me how “ancient maritime history” are so western-centric and completely ignore the oldest sailing cultures in the world: the Austronesians. Even when they do mention it, they only mention the Polynesians and ignore all the rest. Heck, even the crab-claw sail used by most sport sailing boats today are continually misidentified as “lateen” sails. They literally are the first humans to invent ships that could cross oceans. Doing it almost 1500 years before Phoenicians, and they did it in the open oceans of BOTH the Pacific and the Indian oceans, not the relatively protected waters of the Mediterranean. Austronesians colonized places as far apart as Madagascar and Easter Island before the colonial era. The technologies they invented like fore-and-aft sails, outriggers, and multhull ships are now used on almost all modern high-speed sailing and commercial/military ships. They deserve more attention.

Leave a Reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Subscribe to Marine Insight Daily Newsletter

" * " indicates required fields

Marine Engineering

Marine Engine Air Compressor Marine Boiler Oily Water Separator Marine Electrical Ship Generator Ship Stabilizer

Nautical Science

Mooring Bridge Watchkeeping Ship Manoeuvring Nautical Charts Anchoring Nautical Equipment Shipboard Guidelines

Explore

Free Maritime eBooks Premium Maritime eBooks Marine Safety Financial Planning Marine Careers Maritime Law Ship Dry Dock

Shipping News Maritime Reports Videos Maritime Piracy Offshore Safety Of Life At Sea (SOLAS) MARPOL

Ancient Mariners: Transoceanic Voyages Before the Europeans

- Read Later

The idea that humans have been completing transoceanic voyages - traveling the earth via our oceans - before Europeans set sail is, in many people's eyes, an accepted conclusion. Yet it is still debated , resisted, and rejected in many academic circles.

We have seen the work of Hapgood, who theorized a pre-ice age tradition of world mapping which involved an advanced, unknown sea-faring civilization who possessed astonishing abilities. Hapgood based these claims on decades of research into ancient map fragments; the most famous of which, the “Piri Reis” map dating to the 15th century, is believed by him and his team to show the Princess Martha Coast of Queen Maud Land Antarctica and the Palmer Peninsula.

Map of the world by Ottoman admiral Piri Reis, drawn in 1513 but allegedly based on much older maps. ( Public Domain )

Astonishing in itself, the fact that the fragment also appears to show the coastline free of ice is downright spectacular considering, according to research presented by Hapgood, the last time it was ice free was over 6,000 years ago (Hapgood, 1966, P. 93-98). Thus, when we consider an oceanic link say, between South America and the Pacific Islands, it should not be too hard to fathom.

In the realm of physical testing, a famous 1947 expedition saw Norwegian adventurer and ethnographer Thor Heyerdahl set off from Peru to French Polynesia in nothing more than a raft designed and constructed using local materials and techniques.

- Evidence Accumulates for Ancient Transoceanic Voyages, Says Geographer

- Amerigo Vespucci: The Forgotten Explorer Who Named America

The Kon-Tiki Expedition Across the Pacific Ocean by balsa wood raft (1947). (cesar harada/ CC BY NC SA 2.0 )

Yes, Heyerdahl’s journey was a crazy one. Having based most hopes of survival on descriptions of traditional ancient crafts from the indigenous people, the intrepid sea-going adventurer and his five man crew were aiming to prove that trans-oceanic voyages from South America to the Pacific Islands was possible and, after 101 days in treacherous Pacific currents, sailing over 8,000 kilometers (5,000 miles) through barren stretches of nothing but water for as far as the eye can see, the washed-out crew finally broke land in the Tuamotus archipelago in French Polynesia, proving once and for all this trans-Pacific travel was indeed possible.

Heyerdahl’s journey was undisputable. The fact that his boat was constructed in the most basic manner possible simply adds to the notion that even at its most simple form, the notion of trans-oceanic voyage should not be dismissed.

Heyerdahl’s theories on how the people of the Pacific Islands arrived via migration from South America, however, was disputed. Nevertheless, this was in the mid-20th Century and, as of 2014, the U.K’s Independent reported findings that may add support to some of Heyerdahl’s long-put down theory. The discovery of two ancient skulls in Brazil, specifically linked to the indigenous Botocudo peoples, provided the opportunity for genetic testing to be carried out by the Natural History Museum of Denmark; and the results, published in a peer-reviewed journal, suggest the skulls’ “ genomic ancestry is Polynesian , with no detectable Native American component” (Malaspinas, A. S. et al., 2014).

While the possibility that the genetic make-up of skulls was due to “mediated European transport,” the true age of the genetic lineage remains unclear. I believe this may in fact hint to what Heyerdahl had claimed all those decades before - a pre-European expansion across the Pacific.

On the Trail of Early Trans-Pacific Voyagers

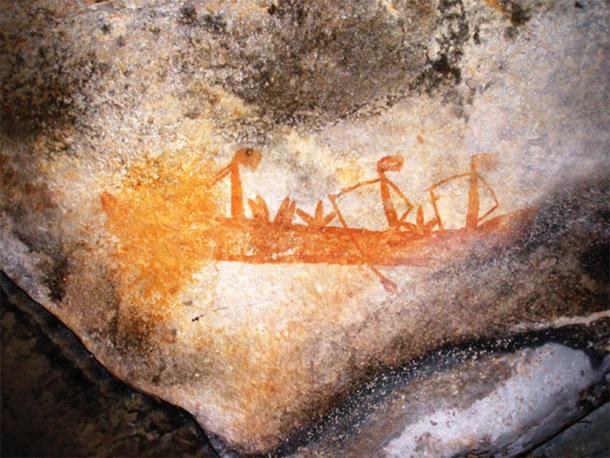

If we were to ask: who could have been sailing at this distant time? - evidence like the “Gwion Gwion” rock art of the Kimberley region , located in the isolated western side of Australia, certainly depicts indigenous people using small boats to pass over open stretches of water. Heyerdahl showed that in this manner they could undergo long-distances.

“Gwion Gwion” rock art depicting a boat, Kimberley, Australia. ( Classconections )

This still does not explain the advanced map fragments. Accurate enough to be better than almost all “modern” maps pre-1900, we see no real evidence for writing-based systems in most of these subsistence-living style cultures who utilized small, human-powered boats. These ancient maps required expertise in the skills of geometry, geography, and a system to efficiently log all of this information.

The skills needed to create these maps must have come from somewhere, but where?

In my previous article, I discussed the fleeting possibility that the Acropolis' initial habitation and construction phases were actually the result of an ancient sea-faring culture, one that many contemporary independent researchers have been on the trail of for years, one who was not only at the heart of the archaic Greek's civilizations during their "golden age", but at the hearts of civilizations across the world - linking North Africa from Egypt to the Anatolian plains through Gobekli Tepe, out through Eurasia by way of Siberia into Europe, and far beyond.

Coincidentally, early 19th century travelers like the English-born doctor and ethnographer Edward Shortland recorded many of the Polynesian and Pacific Island foundation myths (specifically those from New Zealand and Cook Islands Māori population , the Tuamotu archipelago, and Marquesan in French Polynesia) and the locals all tell of how their own sea-faring cultures were created with the help of a first man: “Tiki”. One local told how:

“Tiki taught laws to regulate work, slaying, man-eating: from him men first learnt to observe laws for this thing, and for that thing, the rites to be used for the dead… and other invocations very numerous.” (Shortland, 1882, P. 2)

French Polynesia Tahiti Carved Stone Tiki Statue . ( Tom Nast /Adobe Stock)

While the name changes somewhat, the figures description remains similar whatever island you end up on. Being symbolically connected to the water, Tiki is in the same vein as Oannes in the Middle East, Manu in the Indian subcontinent, Osiris and his followers in North Africa and Quetzalcoatl and Viracocha in the Americas, and the list could keep going on.

It is certainly curious that during the aforementioned Danish study, further testing of over 27 native Rapanui (Easter Islanders) DNA had concluded the genomes were on average about eight percent Native American, suggesting at one time the Rapanui and Native American people had been close in contact.

Again, it is hard to know whether this genetic link was pre or post-European voyage, but maybe certain stone figures from the Pacific Islands - aside from the now world-renowned Easter Island heads - smaller, lesser known sculptures, may hold a clue to where this connection spread from.

The now world-famous, gigantic Easter Island “Moai” heads - most are accompanied with even larger bodies buried under the ground. ( Public Domain )

Stories Set in Stone

Many countries situated around the Pacific Ocean seem to draw parallels with one another, suggesting at one time there was at least one common connection between these amazing yet still so unknown settlements. This can also be seen throughout ancient sculpture.

The meaning behind the “dogu” is still unclear, but it is known that these mysterious Neolithic stone figurines appeared during the Jomon Period within ancient Japan, a strange and undoubtedly unknown time, starting around 14,500 BC and ending close to 1000 BC. The level of detail found in some dogu suggests an exceptional skill of craftsmanship - some are even completely hollow but still able to stand freely on their own.

Theories range on their purpose. The Japanese Times reports how some researchers believe artifacts such as these were designed as “play toys”... the prevalent theory before this was that they were simply ritualistic offerings. Dr. Kaner, an archaeologist specializing in prehistoric Japan from the Sainsbury Institute for the Study of Japanese Arts and Cultures believes “there is scope for both ‘everyday’ figures and objects of veneration within the dogu tradition.”

Dogū (clay figure), Jomon period, 7000-400 BC, Tokyo National Museum. ( CC0 )

The truth is, nobody really knows what these artifacts were used or designed for. Many researchers tend to believe they often represent real historical figures, used to venerate people whom the local population looked up to. This certainly makes sense. From the Egyptians to the Romans, and even in our modern times, we seem to have a penchant for creating large stone sculptures of historical figures we want to idolize.

We know that to be the case with the civilizing figure Tiki, who was traditionally immortalized through stone sculptures found throughout the numerous Polynesian and Pacific islands, thought to have originally represented this civilizing figure himself. In fact, some Polynesian depictions of the founding hero Tiki draw eerily similar senses of artistry to the mysterious dogu figures of prehistoric Japan.

- Mysterious Cocaine Mummies: Do They Prove Ancient Voyages Between Egypt and Americas?

- Adrift at Sea: The Long-Awaited Recovery of the Oldest Message in a Bottle

Pacific Passageways and Tiki

When compared side-by-side, there seems to be an, albeit small, stylized similarity between the “goggle-eyed” dogu from Kamegaoka, the Tōhoku region of northern Japan, and a variation of Tiki of the Polynesian islands.

Most intriguing, the large round, almost oval eyes, both feature horizontal lines separating the center – which is not typical for human eyes - and the fact it appears on both is interesting. Also, while not shown in the given example, many Tikis also featured geometric patterns, as seen on the body of the dogu.

A side-by-side comparison of two sculptures, separated by vast expanses of turbulent ocean. To the right, the “goggle-eyed” dogu from Kamegaoka, late Jomon period (1,000- 400 BC) ( CC BY SA 4.0 ) and to the left, a Tiki sculpture found in the Marquesas Islands, French Polynesia ( Public Domain ).

Admittedly, the similarity is small. But given everything else we know about newly understood migration patterns and advanced ancient mapping, I decided to pursue it further. Could exploring the history of the Tiki help provide some clarity?

I contacted an Oceanic Art specialist and, while I’ll omit his name, I can say that he works for a very prestigious and long-lasting antique auction house and dealership business. Among a multitude of interesting things, he pointed out that there is a considerable “...lack of historical material documenting the precise provenance” regarding these (Tiki) sculptures.”

“Most of these objects have been collected randomly… without any written documentation [and] arrived in Europe in the late XIXth century” he went on to tell me, ending his correspondence by making clear that we should “not exclude them from being older than from this time.” Thus, just like the dogu, we are left rather unsure as to where, when, or why these Tiki sculptures appeared in the Pacific Islands.

Could there have been some sort of oceanic connection between Japan and Polynesia that spread this style? Could it have come from one single, ancient source?

A 2012 study of edge-ground axe heads in Japan, dating to 38,000 - 32,000 years ago (Takashi, 2012, Pp. 70-78) certainly highlights the fact that, due to the heads being created from obsidian, a material only found on the island of Hokkaido , the earliest humans in Japan would have enjoyed access to sea-faring crafts which allowed them to process this sought-after material.

An Ainu man, one of Hokkaido's indigenous people. ( Public Domain )

The distances would have started small but, according to archaeologists Glascock and Kuzmin, they eventually rose to over 1000 kilometers (621.37 miles) during the Upper Paleolithic (around 50,000-10,000 years ago) (2007, Pp. 99-120).

While this is not conclusive proof that Japanese islanders were in contact with South Pacific populations or vice versa, the possibility of some form of prehistoric connection should not be readily dismissed.

Further Afield

The intrigue continues when we learn that this superficial artistic link does not just stop with these Pacific cultures. I have also noticed a similarity between various dogu sculptures and figures found in the Lepenski-Vir archaeological site. This is located all the way to the west, a journey of, as the crow flies, over 8,000 km (4970.97 miles) in modern day Serbia.

From Ph.D. research in the Department of Archaeology within the University of Cambridge, Dr. Borić claims the Serbian site dates back to 8,200 BC (2002, p.1030) and the so called “Progenetrix” sculpture is from the 7,000 BC strata - well within the Jomon time period.

Obvious similarities arise:

- The facial expressions - notably exhibiting a look akin to “shock” or “surprise.”

- The small, circular, ringed eyes, both seeming to be deliberately depicted looking up.

- The rounded, triangular shape of the face.

- The geometric-style pattern engraved around the body.

- The position of the hands - seeming to curl inwards, resting on the torso.

With the notion that the Japanese Jomon period lasted for close to 14,000 years, the possibility that they were in contact with areas as far out as Polynesia or Serbia does not seem too crazy.

Considering nothing is really discussed about this in the local records, this also opens up the possibility that they were in fact not the originators of this connection, but simply part of the instance of locals being contacted by other civilizations, yet unknown, who also traveled west across Eurasia, eventually to Serbia during the Lepenski-Vir period, and also south-east by means of oceanic voyage down to the Pacific Islands.

The Lepenski-Vir “Progenetrix” figure to the left ( CC BY SA 4.0 ) and its dogu counterpart to the right. ( Public Domain )

Questions Remaining about Early Transoceanic Voyages

Seeing as it’s almost a given that ancient civilizations were traveling the world, via our oceans, long before the uncompromising waves of Europeans broke over the distant shores, this leaves the question very much open for when the earliest examples of sea-exploration were.

- Antarctica's Ancient Origins Update – Part Two: Did Early Voyagers Leave Evidence?

- The Legend of How Mansa Abu Bakr II of Mali Gave up the Throne to Explore the Atlantic Ocean

What does this mean for the origins of advanced sea faring civilizations?

Who could have been at the genesis of this oceanic expansion?

I find the question of whether these ancient maps really did find themselves beginning with someone who was staring at the Antarctic coast , ice-free, armed with the tools and knowledge necessary to illustrate precise maps of what lay in front of them, many thousands of years ago, highly compelling.

Were these the same people who then proceeded to systematically visit and embed themselves among emerging ancient cultures all over the world?

The only way to find out is to keep searching for answers - some will be a lot deeper than others.

Top Image: Representation of an ancient transoceanic voyage. Source: pawopa3336 /Adobe Stock

By Freddie Levy

Anderson, A., Chappell, J., Gagan, M., & Grove, R. 2006. Prehistoric maritime migration in the Pacific islands: an hypothesis of ENSO forcing in The Holocene . 16 (1), P. 1. [Accessed: https://doi.org/10.1191/0959683606hl901ft ]

Barnes, S.S. et al. 2006. Ancient DNA of the Pacific rat (Rattus exulans) from Rapa Nui (Easter Island) in Journal of Archaeological Science . [online]. 33 (11). Pp. 1536–1540

BBC. September 21, 2018. Prehistoric art hints at lost Indian civilisation. [Accessed: https://www.bbc.co.uk/news]

Borić, D. 2002. The Lepenski Vir conundrum: Reinterpretation of the Mesolithic and Neolithic sequences in the Danube Gorges in Antiquity . 76 (294), Pp. 1026-1039. [Accessed: http://orca.cf.ac.uk/39454/1/Antiquity-2002.pdf ]

Clarkson, C et. al. 19 July 2017. Human occupation of northern Australia by 65,000 years ago in Nature . 547 (7663): 306–310. [Accessed: https://digital.library.adelaide.edu.au/]

Connor, S. October 23, 2014. New discoveries show more contact between far-flung prehistoric humans than first thought in The Independent [online]. [Accessed: here ]

Cotterell, M. 2003. The Lost Tomb of Viracocha: Unlocking the Secrets of the Peruvian Pyramids . New York: Simon and Schuster.

Glascock, M. D. Kuzmin, Y. V. 2007. Two Islands in the Ocean: Prehistoric Obsidian Exchange between Sakhalin and Hokkaido, Northeast Asia in The Journal of Island and Coastal Archaeology . 2.1. Pp. 99-120.

Hancock, G. 2015. Magicians of the Gods. United Kingdom: Coronet.

Hapgood, C. H. Maps of the Ancient Sea Kings . Philadelphia and New York: Chilton Books, 1966, P. 243.

James, V. October, 2009. The dogu have something to tell us in The Japanese Times . [Accessed: https://www.japantimes.co.jp/culture/2009/10/02/arts/the-dogu-have-something-to-tell-us/#.XlTD8JNKjOR ]

Malaspinas, A. S. et al., November 3, 2014. Two ancient human genomes reveal Polynesian ancestry among the indigenous Botocudos of Brazil in Current Biology 24/21, Pp. R1035-R1037

Matisoo-Smith, E. Robins, J. H. June, 2004. Origins and dispersals of Pacific peoples: Evidence from mtDNA phylogenies of the Pacific rat in Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences , 101 (24) Pp. 9167-9172. (DOI: 10.1073/pnas.0403120101)

Schmidt, G. A., Frank, A. 2018. The Silurian Hypothesis: Would It Be Possible to Detect an Industrial Civilization in the Geological Record? in International Journal of Astrobiology . 18.2: 142–150. [Accessed: https://arxiv.org/abs/1804.03748]

Shortland, E. 1882. Maori Religion and Mythology. Longman, Green: London.

Takashi, T. January, 2012. MIS3 edge-ground axes and the arrival of the first Homo sapiens in the Japanese archipelago in Quaternary International , 248 , Pp. 70-78.

van den Hoven, S. 2019. The vedic relations of early religion in India and Europe . [Accessed: https://www.academia.edu ]

Great suggestion Sigerico!

I've briefly looked through the book before (admittedly it's very dense so was more of a skim) - Higgins' theories were definetely out of the norm for his time, and whilst he is very heavy on the religion-side of analysis, I do find his theory on ancient Chinese and Indian expansion to explain common demoninators in culture and religion compelling.

I tend to lean away from Higgins' view that the similarities in various religious figures is based around the zodiac constellations and that "God" is the sun alone, and I move more towards the theory that these religious characters were based on actual figures who were only immortalised due to their extreme knowledge, albeit it with certain symbology encoded throughout the myth and religion as well.

Your right about navigating without sight of land. Whether by learned esoteric knowledge on how to read and navigate by the stars, to unknown or yet not fully understood technology (take the Antikythera mechanism for example), ancient people could for sure navigate accurately over extreme distances.

Interesting that you think the site of "Atlantis" (basically a lost ancient sea-faring culture mentioned famously by Plato) is in Indonesia. What leads you to those conclusions? I subscribe to Randal Carlson's theory that the ancient sea-faring culture was actually located within the Azores archipelago, off the coast of Portugal. I am always open to other interpretations... Thanks for the comment!

you should read old books like Anacalypsis by Godfrey Higgins, published in 1840. he goes into these transoceanic voyages in ice age times. there was ship traffic across the Indian Ocean in Roman times and earlier. ocean going wooden ships are built to the same design to this day in Kerala.

they were perfectly capable of navigating out of sight of land. that's why there are pyramid cultures all around the world. they were all built by the same people.

the whole world probably had a common culture and language, either Sanskrit or something similar.

Atlantis may have been the origin, most likely on the equator in Indonesia. the Java Sea is only 50 metres deep, so with sea levels being 200 metres lower during the last ice age vast areas of land would have been exposed.

After obtaining a BA Honours in Classics from the University of Leeds, and a PGDE from University College London, a flexible schedule as a Design and Technology teacher has led me to spend long periods of time living abroad. I... Read More

Related Articles on Ancient-Origins

Smithsonian Ocean

- Ancient Seas

The Ocean Throughout Geologic Time

The ocean has gone through some dramatic transformations over time. This overview dives into our globe's ocean past.

Rudist Reefs

The Megalodon

Foraminifera

Coral Reefs Changing Over Time

4,000 Years of Marine History through the Eyes of a Seabird

Are you an educator.

Long Before Coral, Mollusks Built the Ocean's Reefs

Archaeologists Study Early Whaling Community in Quebec, Canada

Shark Teeth Tell Great White Shark Evolution Story

When Did Today’s Whales Get So Big?

Expedition to Excavate a Fossil Whale

At STRI, No Whales Yet, But There Are Fossil Sea Cows...

Fossil Whale Found, Excavated, Jacketed, and Returned to STRI!

New Archaeocetes from Peru Are the Oldest Fossil Whales from South America

The Discovery of Multispecies Communities of Seacows

Smithsonian Scientists Describe a 'New' Fossil Whale

Excavating a "toothed" baleen whale from Vancouver Island

Dispatches from the Field: Treacherous stream crossings and a new fossil find

- Filter by: All

- Geologic periods

- New discoveries

- Paleobiology

- Ancient sea life

Smithsonian Institution

- Marine Mammals

- Sharks & Rays

- Invertebrates

- Plants & Algae

- Coral Reefs

- Coasts & Shallow Water

- Census of Marine Life

- Tides & Currents

- Waves, Storms & Tsunamis

- The Seafloor

- Temperature & Chemistry

- Extinctions

- The Anthropocene

- Habitat Destruction

- Invasive Species

- Acidification

- Climate Change

- Gulf Oil Spill

- Solutions & Success Stories

- Get Involved

- Books, Film & The Arts

- Exploration

- History & Cultures

- At The Museum

Search Smithsonian Ocean

- Search Menu

- Sign in through your institution

- Browse content in Arts and Humanities

- Browse content in Archaeology

- Anglo-Saxon and Medieval Archaeology

- Archaeological Methodology and Techniques

- Archaeology by Region

- Archaeology of Religion

- Archaeology of Trade and Exchange

- Biblical Archaeology

- Contemporary and Public Archaeology

- Environmental Archaeology

- Historical Archaeology

- History and Theory of Archaeology

- Industrial Archaeology

- Landscape Archaeology

- Mortuary Archaeology

- Prehistoric Archaeology

- Underwater Archaeology

- Zooarchaeology

- Browse content in Architecture

- Architectural Structure and Design

- History of Architecture

- Residential and Domestic Buildings

- Theory of Architecture

- Browse content in Art

- Art Subjects and Themes

- History of Art

- Industrial and Commercial Art

- Theory of Art

- Biographical Studies

- Byzantine Studies

- Browse content in Classical Studies

- Classical History

- Classical Philosophy

- Classical Mythology

- Classical Numismatics

- Classical Literature

- Classical Reception

- Classical Art and Architecture

- Classical Oratory and Rhetoric

- Greek and Roman Epigraphy

- Greek and Roman Law

- Greek and Roman Papyrology

- Greek and Roman Archaeology

- Late Antiquity

- Religion in the Ancient World

- Social History

- Digital Humanities

- Browse content in History

- Colonialism and Imperialism

- Diplomatic History

- Environmental History

- Genealogy, Heraldry, Names, and Honours

- Genocide and Ethnic Cleansing

- Historical Geography

- History by Period

- History of Emotions

- History of Agriculture

- History of Education

- History of Gender and Sexuality

- Industrial History

- Intellectual History

- International History

- Labour History

- Legal and Constitutional History

- Local and Family History

- Maritime History

- Military History

- National Liberation and Post-Colonialism

- Oral History

- Political History

- Public History

- Regional and National History

- Revolutions and Rebellions

- Slavery and Abolition of Slavery

- Social and Cultural History

- Theory, Methods, and Historiography

- Urban History

- World History

- Browse content in Language Teaching and Learning

- Language Learning (Specific Skills)

- Language Teaching Theory and Methods

- Browse content in Linguistics

- Applied Linguistics

- Cognitive Linguistics

- Computational Linguistics

- Forensic Linguistics

- Grammar, Syntax and Morphology

- Historical and Diachronic Linguistics

- History of English

- Language Acquisition

- Language Evolution

- Language Reference

- Language Variation

- Language Families

- Lexicography

- Linguistic Anthropology

- Linguistic Theories

- Linguistic Typology

- Phonetics and Phonology

- Psycholinguistics

- Sociolinguistics

- Translation and Interpretation

- Writing Systems

- Browse content in Literature

- Bibliography

- Children's Literature Studies

- Literary Studies (Asian)

- Literary Studies (European)

- Literary Studies (Eco-criticism)

- Literary Studies (Romanticism)

- Literary Studies (American)

- Literary Studies (Modernism)

- Literary Studies - World

- Literary Studies (1500 to 1800)

- Literary Studies (19th Century)

- Literary Studies (20th Century onwards)

- Literary Studies (African American Literature)

- Literary Studies (British and Irish)

- Literary Studies (Early and Medieval)

- Literary Studies (Fiction, Novelists, and Prose Writers)

- Literary Studies (Gender Studies)

- Literary Studies (Graphic Novels)

- Literary Studies (History of the Book)

- Literary Studies (Plays and Playwrights)

- Literary Studies (Poetry and Poets)

- Literary Studies (Postcolonial Literature)

- Literary Studies (Queer Studies)

- Literary Studies (Science Fiction)

- Literary Studies (Travel Literature)

- Literary Studies (War Literature)

- Literary Studies (Women's Writing)

- Literary Theory and Cultural Studies

- Mythology and Folklore

- Shakespeare Studies and Criticism

- Browse content in Media Studies

- Browse content in Music

- Applied Music

- Dance and Music

- Ethics in Music

- Ethnomusicology

- Gender and Sexuality in Music

- Medicine and Music

- Music Cultures

- Music and Religion

- Music and Media

- Music and Culture

- Music Education and Pedagogy

- Music Theory and Analysis

- Musical Scores, Lyrics, and Libretti

- Musical Structures, Styles, and Techniques

- Musicology and Music History

- Performance Practice and Studies

- Race and Ethnicity in Music

- Sound Studies

- Browse content in Performing Arts

- Browse content in Philosophy

- Aesthetics and Philosophy of Art

- Epistemology

- Feminist Philosophy

- History of Western Philosophy

- Metaphysics

- Moral Philosophy

- Non-Western Philosophy

- Philosophy of Science

- Philosophy of Language

- Philosophy of Mind

- Philosophy of Perception

- Philosophy of Action

- Philosophy of Law

- Philosophy of Religion

- Philosophy of Mathematics and Logic

- Practical Ethics

- Social and Political Philosophy

- Browse content in Religion

- Biblical Studies

- Christianity

- East Asian Religions

- History of Religion

- Judaism and Jewish Studies

- Qumran Studies

- Religion and Education

- Religion and Health

- Religion and Politics

- Religion and Science

- Religion and Law

- Religion and Art, Literature, and Music

- Religious Studies

- Browse content in Society and Culture

- Cookery, Food, and Drink

- Cultural Studies

- Customs and Traditions

- Ethical Issues and Debates

- Hobbies, Games, Arts and Crafts

- Natural world, Country Life, and Pets

- Popular Beliefs and Controversial Knowledge

- Sports and Outdoor Recreation

- Technology and Society

- Travel and Holiday

- Visual Culture

- Browse content in Law

- Arbitration

- Browse content in Company and Commercial Law

- Commercial Law

- Company Law

- Browse content in Comparative Law

- Systems of Law

- Competition Law

- Browse content in Constitutional and Administrative Law

- Government Powers

- Judicial Review

- Local Government Law

- Military and Defence Law

- Parliamentary and Legislative Practice

- Construction Law

- Contract Law

- Browse content in Criminal Law

- Criminal Procedure

- Criminal Evidence Law

- Sentencing and Punishment

- Employment and Labour Law

- Environment and Energy Law

- Browse content in Financial Law

- Banking Law

- Insolvency Law

- History of Law

- Human Rights and Immigration

- Intellectual Property Law

- Browse content in International Law

- Private International Law and Conflict of Laws

- Public International Law

- IT and Communications Law

- Jurisprudence and Philosophy of Law

- Law and Politics

- Law and Society

- Browse content in Legal System and Practice

- Courts and Procedure

- Legal Skills and Practice

- Legal System - Costs and Funding

- Primary Sources of Law

- Regulation of Legal Profession

- Medical and Healthcare Law

- Browse content in Policing

- Criminal Investigation and Detection

- Police and Security Services

- Police Procedure and Law

- Police Regional Planning

- Browse content in Property Law

- Personal Property Law

- Restitution

- Study and Revision

- Terrorism and National Security Law

- Browse content in Trusts Law

- Wills and Probate or Succession

- Browse content in Medicine and Health

- Browse content in Allied Health Professions

- Arts Therapies

- Clinical Science

- Dietetics and Nutrition

- Occupational Therapy

- Operating Department Practice

- Physiotherapy

- Radiography

- Speech and Language Therapy

- Browse content in Anaesthetics

- General Anaesthesia

- Browse content in Clinical Medicine

- Acute Medicine

- Cardiovascular Medicine

- Clinical Genetics

- Clinical Pharmacology and Therapeutics

- Dermatology

- Endocrinology and Diabetes

- Gastroenterology

- Genito-urinary Medicine

- Geriatric Medicine

- Infectious Diseases

- Medical Toxicology

- Medical Oncology

- Pain Medicine

- Palliative Medicine

- Rehabilitation Medicine

- Respiratory Medicine and Pulmonology

- Rheumatology

- Sleep Medicine

- Sports and Exercise Medicine

- Clinical Neuroscience

- Community Medical Services

- Critical Care

- Emergency Medicine

- Forensic Medicine

- Haematology

- History of Medicine

- Browse content in Medical Dentistry

- Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery

- Paediatric Dentistry

- Restorative Dentistry and Orthodontics

- Surgical Dentistry

- Browse content in Medical Skills

- Clinical Skills

- Communication Skills

- Nursing Skills

- Surgical Skills

- Medical Ethics

- Medical Statistics and Methodology

- Browse content in Neurology

- Clinical Neurophysiology

- Neuropathology

- Nursing Studies

- Browse content in Obstetrics and Gynaecology

- Gynaecology

- Occupational Medicine

- Ophthalmology

- Otolaryngology (ENT)

- Browse content in Paediatrics

- Neonatology

- Browse content in Pathology

- Chemical Pathology

- Clinical Cytogenetics and Molecular Genetics

- Histopathology

- Medical Microbiology and Virology

- Patient Education and Information

- Browse content in Pharmacology

- Psychopharmacology

- Browse content in Popular Health

- Caring for Others

- Complementary and Alternative Medicine

- Self-help and Personal Development

- Browse content in Preclinical Medicine

- Cell Biology

- Molecular Biology and Genetics

- Reproduction, Growth and Development

- Primary Care

- Professional Development in Medicine

- Browse content in Psychiatry

- Addiction Medicine

- Child and Adolescent Psychiatry

- Forensic Psychiatry

- Learning Disabilities

- Old Age Psychiatry

- Psychotherapy

- Browse content in Public Health and Epidemiology

- Epidemiology

- Public Health

- Browse content in Radiology

- Clinical Radiology

- Interventional Radiology

- Nuclear Medicine

- Radiation Oncology

- Reproductive Medicine

- Browse content in Surgery

- Cardiothoracic Surgery

- Gastro-intestinal and Colorectal Surgery

- General Surgery

- Neurosurgery

- Paediatric Surgery

- Peri-operative Care

- Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery

- Surgical Oncology

- Transplant Surgery

- Trauma and Orthopaedic Surgery

- Vascular Surgery

- Browse content in Science and Mathematics

- Browse content in Biological Sciences

- Aquatic Biology

- Biochemistry

- Bioinformatics and Computational Biology

- Developmental Biology

- Ecology and Conservation

- Evolutionary Biology

- Genetics and Genomics

- Microbiology

- Molecular and Cell Biology

- Natural History

- Plant Sciences and Forestry

- Research Methods in Life Sciences

- Structural Biology

- Systems Biology

- Zoology and Animal Sciences

- Browse content in Chemistry

- Analytical Chemistry

- Computational Chemistry

- Crystallography

- Environmental Chemistry

- Industrial Chemistry

- Inorganic Chemistry

- Materials Chemistry

- Medicinal Chemistry

- Mineralogy and Gems

- Organic Chemistry

- Physical Chemistry

- Polymer Chemistry

- Study and Communication Skills in Chemistry

- Theoretical Chemistry

- Browse content in Computer Science

- Artificial Intelligence

- Computer Architecture and Logic Design

- Game Studies

- Human-Computer Interaction

- Mathematical Theory of Computation

- Programming Languages

- Software Engineering

- Systems Analysis and Design

- Virtual Reality

- Browse content in Computing

- Business Applications

- Computer Security

- Computer Games

- Computer Networking and Communications

- Digital Lifestyle

- Graphical and Digital Media Applications

- Operating Systems

- Browse content in Earth Sciences and Geography

- Atmospheric Sciences

- Environmental Geography

- Geology and the Lithosphere

- Maps and Map-making

- Meteorology and Climatology

- Oceanography and Hydrology

- Palaeontology

- Physical Geography and Topography

- Regional Geography

- Soil Science

- Urban Geography

- Browse content in Engineering and Technology

- Agriculture and Farming

- Biological Engineering

- Civil Engineering, Surveying, and Building

- Electronics and Communications Engineering

- Energy Technology

- Engineering (General)

- Environmental Science, Engineering, and Technology

- History of Engineering and Technology

- Mechanical Engineering and Materials

- Technology of Industrial Chemistry

- Transport Technology and Trades

- Browse content in Environmental Science

- Applied Ecology (Environmental Science)

- Conservation of the Environment (Environmental Science)

- Environmental Sustainability

- Environmentalist Thought and Ideology (Environmental Science)

- Management of Land and Natural Resources (Environmental Science)

- Natural Disasters (Environmental Science)

- Nuclear Issues (Environmental Science)

- Pollution and Threats to the Environment (Environmental Science)

- Social Impact of Environmental Issues (Environmental Science)

- History of Science and Technology

- Browse content in Materials Science

- Ceramics and Glasses

- Composite Materials

- Metals, Alloying, and Corrosion

- Nanotechnology

- Browse content in Mathematics

- Applied Mathematics

- Biomathematics and Statistics

- History of Mathematics

- Mathematical Education

- Mathematical Finance

- Mathematical Analysis

- Numerical and Computational Mathematics

- Probability and Statistics

- Pure Mathematics

- Browse content in Neuroscience

- Cognition and Behavioural Neuroscience

- Development of the Nervous System

- Disorders of the Nervous System

- History of Neuroscience

- Invertebrate Neurobiology

- Molecular and Cellular Systems

- Neuroendocrinology and Autonomic Nervous System

- Neuroscientific Techniques

- Sensory and Motor Systems

- Browse content in Physics

- Astronomy and Astrophysics

- Atomic, Molecular, and Optical Physics

- Biological and Medical Physics

- Classical Mechanics

- Computational Physics

- Condensed Matter Physics

- Electromagnetism, Optics, and Acoustics

- History of Physics

- Mathematical and Statistical Physics

- Measurement Science

- Nuclear Physics

- Particles and Fields

- Plasma Physics

- Quantum Physics

- Relativity and Gravitation

- Semiconductor and Mesoscopic Physics

- Browse content in Psychology

- Affective Sciences

- Clinical Psychology

- Cognitive Psychology

- Cognitive Neuroscience

- Criminal and Forensic Psychology

- Developmental Psychology

- Educational Psychology

- Evolutionary Psychology

- Health Psychology

- History and Systems in Psychology

- Music Psychology

- Neuropsychology

- Organizational Psychology

- Psychological Assessment and Testing

- Psychology of Human-Technology Interaction

- Psychology Professional Development and Training

- Research Methods in Psychology

- Social Psychology

- Browse content in Social Sciences

- Browse content in Anthropology

- Anthropology of Religion

- Human Evolution

- Medical Anthropology

- Physical Anthropology

- Regional Anthropology

- Social and Cultural Anthropology

- Theory and Practice of Anthropology

- Browse content in Business and Management

- Business Strategy

- Business Ethics

- Business History

- Business and Government

- Business and Technology

- Business and the Environment

- Comparative Management

- Corporate Governance

- Corporate Social Responsibility

- Entrepreneurship

- Health Management

- Human Resource Management

- Industrial and Employment Relations

- Industry Studies

- Information and Communication Technologies

- International Business

- Knowledge Management

- Management and Management Techniques

- Operations Management

- Organizational Theory and Behaviour

- Pensions and Pension Management

- Public and Nonprofit Management

- Social Issues in Business and Management

- Strategic Management

- Supply Chain Management

- Browse content in Criminology and Criminal Justice

- Criminal Justice

- Criminology

- Forms of Crime

- International and Comparative Criminology

- Youth Violence and Juvenile Justice

- Development Studies

- Browse content in Economics

- Agricultural, Environmental, and Natural Resource Economics

- Asian Economics

- Behavioural Finance

- Behavioural Economics and Neuroeconomics

- Econometrics and Mathematical Economics

- Economic Systems

- Economic History

- Economic Methodology

- Economic Development and Growth

- Financial Markets

- Financial Institutions and Services

- General Economics and Teaching

- Health, Education, and Welfare

- History of Economic Thought

- International Economics

- Labour and Demographic Economics

- Law and Economics

- Macroeconomics and Monetary Economics

- Microeconomics

- Public Economics

- Urban, Rural, and Regional Economics

- Welfare Economics

- Browse content in Education

- Adult Education and Continuous Learning

- Care and Counselling of Students

- Early Childhood and Elementary Education

- Educational Equipment and Technology

- Educational Strategies and Policy

- Higher and Further Education

- Organization and Management of Education

- Philosophy and Theory of Education

- Schools Studies

- Secondary Education

- Teaching of a Specific Subject

- Teaching of Specific Groups and Special Educational Needs

- Teaching Skills and Techniques

- Browse content in Environment

- Applied Ecology (Social Science)

- Climate Change

- Conservation of the Environment (Social Science)

- Environmentalist Thought and Ideology (Social Science)

- Management of Land and Natural Resources (Social Science)

- Natural Disasters (Environment)

- Pollution and Threats to the Environment (Social Science)

- Social Impact of Environmental Issues (Social Science)

- Sustainability

- Browse content in Human Geography

- Cultural Geography

- Economic Geography

- Political Geography

- Browse content in Interdisciplinary Studies

- Communication Studies

- Museums, Libraries, and Information Sciences

- Browse content in Politics

- African Politics

- Asian Politics

- Chinese Politics

- Comparative Politics

- Conflict Politics

- Elections and Electoral Studies

- Environmental Politics

- Ethnic Politics

- European Union

- Foreign Policy

- Gender and Politics

- Human Rights and Politics

- Indian Politics

- International Relations

- International Organization (Politics)

- Irish Politics

- Latin American Politics

- Middle Eastern Politics

- Political Methodology

- Political Communication

- Political Philosophy

- Political Sociology

- Political Behaviour

- Political Economy

- Political Institutions

- Political Theory

- Politics and Law

- Politics of Development

- Public Administration

- Public Policy

- Qualitative Political Methodology

- Quantitative Political Methodology

- Regional Political Studies

- Russian Politics

- Security Studies

- State and Local Government

- UK Politics

- US Politics

- Browse content in Regional and Area Studies

- African Studies

- Asian Studies

- East Asian Studies

- Japanese Studies

- Latin American Studies

- Middle Eastern Studies

- Native American Studies

- Scottish Studies

- Browse content in Research and Information

- Research Methods

- Browse content in Social Work

- Addictions and Substance Misuse

- Adoption and Fostering

- Care of the Elderly

- Child and Adolescent Social Work

- Couple and Family Social Work

- Direct Practice and Clinical Social Work

- Emergency Services

- Human Behaviour and the Social Environment

- International and Global Issues in Social Work

- Mental and Behavioural Health

- Social Justice and Human Rights

- Social Policy and Advocacy

- Social Work and Crime and Justice

- Social Work Macro Practice

- Social Work Practice Settings

- Social Work Research and Evidence-based Practice

- Welfare and Benefit Systems

- Browse content in Sociology

- Childhood Studies

- Community Development

- Comparative and Historical Sociology

- Disability Studies

- Economic Sociology

- Gender and Sexuality

- Gerontology and Ageing

- Health, Illness, and Medicine

- Marriage and the Family

- Migration Studies

- Occupations, Professions, and Work

- Organizations

- Population and Demography

- Race and Ethnicity

- Social Theory

- Social Movements and Social Change

- Social Research and Statistics

- Social Stratification, Inequality, and Mobility

- Sociology of Religion

- Sociology of Education

- Sport and Leisure

- Urban and Rural Studies

- Browse content in Warfare and Defence

- Defence Strategy, Planning, and Research

- Land Forces and Warfare

- Military Administration

- Military Life and Institutions

- Naval Forces and Warfare

- Other Warfare and Defence Issues

- Peace Studies and Conflict Resolution

- Weapons and Equipment

- < Previous chapter

- Next chapter >

Travel in the Roman World

Dartmouth College

- Published: 07 March 2016

- Cite Icon Cite

- Permissions Icon Permissions

This article examines Roman travel. It seeks to show how deeply travel was woven into the fabric of the ancient world and how many aspects of the Roman experience relate to it. Rather than pretend to total coverage, this article, which is divided into four sections, offers some ways of thinking about travel and its place in the Roman world, exploring the practice, ideology, and imagination of travel. Moving from a top-down perspective on Roman infrastructure and the role of travel in the practice of Roman power, the article turns to a bottom-up view of the experiences of individuals when traveling, concluding with a survey of the imaginative representation of travel in the literature of the Roman world.

Introduction

I see you know that I arrived in Tusculum on November 14th. Dionysius was there waiting for me. I want to be in Rome on the 18th. I say “want,” but really I have to be there—it’s Milo’s wedding. (Cic. ad Att. 4.13.1 = no. 87 SB; trans. Shackleton Bailey)

So Cicero writes to Atticus in the middle of November 55 BCE, asking for an update on the political situation in the capital. His tongue-in-cheek tone—he has ( cogimur ) to be in town for a wedding—belies both his urgent request for information and the complex network of roads and technologies of travel on which his upcoming trip depends. Neither Cicero’s letter nor his mini-break away from the city are out of place in his correspondence from the mid-50s. On Shackleton Bailey’s dating, twenty-nine letters survive from the years 56 and 55; nearly half were written outside Rome. We learn from those letters that Cicero traveled to Tusculum, Cumae, Napes, Pompeii, and Antium. In other years he ventured even farther afield. When he was reluctantly made governor of Cilicia in 51, he recounted his journey there in a series of plaintive missives to Atticus, griping, for instance, about “waiting for a passage” after being held up for twelve days in Brundisium by an “indisposition” ( ad Att. 5.8.1 = 101 SB; trans. Shackleton Bailey). The only thing worse than waiting for a ship was being a passenger on one; a month later he grumbles from Delos: “Travelling by sea is no light matter, even in July…. You know these Rhodian open ships—nothing makes heavier weather” ( ad Att. 5.12.1 = 105 SB; trans. Shackleton Bailey).