History of the Circus

Circus is a name for a traveling company of performers. These performers are usually acrobats, clowns, and trained animals, although circuses have musicians, trapeze, and other stunt artists. Circuses typically perform in a circus tent. The circus is more of an art form than a pure show today.

Circus History and Origin

Some say that the history of the circus began in the 18th century. Some say that the history of the circus begins in ancient Rome. We believe them and discuss all important points from the circus origins here.

Circus Facts and Trivia

Circuses strive to be colorful and to capture the attention of the audience. They enlist various people with different skills and train different animals to do many tricks to achieve that. And in that striving, they can go too far.

Different Famous Circuses

As we all know, wild animals can be dangerous, heights can be dangerous, and neglect can be dangerous. Mix all that, and you get a big part of the circus. These aspects brought some of the most serious accidents in circus history.

Some say that the circus appeared for the first time in the 18th century, and if we look at the origins of the modern circus, they may be right. But the first circuses appeared in Ancient Rome, where horse and chariot races were held, along with staged battles, gladiatorial combat, and displays of trained animals. The circus of that time was the only public spectacle at which men and women were not separated. The earliest circus in Rome was the Circus Maximus, built in the Old Kingdom era. When finished, it could receive 250,000 people, 400m long and 90m wide. Circus Flaminius, Circus Neronis, and Circus of Maxentius are other famous circuses of the Roman era.

The modern circus began in the 18th century with Philip Astley, a cavalry officer from England. He opened an amphitheater in Lambeth, London, on 4 April 1768 to display horse riding tricks. Tricks were not his invention, but he was the first to build a place for their performance in front of an audience. He called this performance arena a Circle and the building an amphitheater, but they became known in time as Circus. Andrew Ducrow continued after Astley and was, at the time, proprietor of his Amphitheater. The first mainstream clown was Joseph Grimaldi with his role of Little Clown in the pantomime “The Triumph of Mirth, or Harlequin's Wedding,” in 1781. Charles Dibdin and his partner Charles Hughes opened The Royal Circus in London on 4 November 1782. Astley exported his Circus to France in the same year as “Amphithéâtre Anglais” and then continued to build 18 more throughout Europe. All these circuses were in specially made buildings for them. Tents appeared later.

The first modern circus in the United States was one in Philadelphia, founded by John Bill Ricketts on April 3, 1793. “The Circus of Pepin and Breschard” toured from Montreal to Havana in the first two decades of the 19th century, and they built many circus buildings along the way. Joshuah Purdy was the first to use a large tent for his circus, and he did it in 1825. Thomas Taplin Cooke brought a tent to England in 1838. Because tents were easier to use, they slowly replaced circus buildings, retrofitted buildings, and open spaces. One of the largest (if not the largest traveling circus) was “The Barnum & Bailey Greatest Show On Earth,” which toured from 1897 to 1902. Under the wish by Lenin for the circus to become “the people's art form,” the USSR nationalized Russian circuses in 1919 and opened the State University of Circus and Variety Arts, better known as the Moscow Circus School, in 1927.

What we call today a “Contemporary circus” (or “nouveau cirque”) appeared in the 1970s in many places like Australia, Canada, France, the West Coast of the United States, and the United Kingdom. This circus still has traditional acts but combines them with theatrical techniques to tell a story or present a theme. The earliest examples of the contemporary circus are Circus Oz, formed in Australia in 1978 from SoapBox Circus and New Circus; Pickle Family Circus, formed in San Francisco in 1975; and Cirque du Soleil, founded in Quebec in 1984. Modern are the Tiger Lillies, Le Cirque Invisible, Dislocate, and Vulcana Women's Circus.

Definition of 'circus'

Image of circus

Video: pronunciation of circus

circus in American English

Circus in british english, examples of 'circus' in a sentence circus, word lists with circus.

Quick word challenge

Quiz Review

Score: 0 / 5

More idioms containing circus

Related word partners circus, trends of circus.

View usage over: Since Exist Last 10 years Last 50 years Last 100 years Last 300 years

Browse alphabetically circus

- circumvent the restrictions

- circumvolution

- circumvolve

- circus animal

- circus catch

- Circus Maximus

- All ENGLISH words that begin with 'C'

Related terms of circus

- flea circus

- tent circus

- circus troupe

- View more related words

Wordle Helper

Scrabble Tools

From Barnum & Bailey to Annie Oakley: History of traveling entertainment in America

Hemingway once wrote: “The circus is the only ageless delight that you can buy for money.” Indeed, traveling entertainment in all of its forms—circuses as well as carnivals, musical performances, etc.—has always been, as Hemingway notes, delightful in some regard.

Where Hemingway is wrong, though, is that the delight of the circus—and all forms of traveling entertainment that have evolved alongside it—is hardly ageless. A close examination of entertainment throughout history will quickly highlight just how much particular forms of entertainment were products of their times, such that they could never be considered enjoyable in the same way today.

Take, for example, the tradition of the medicine show. This was a spectacle in which a troupe of performers puts on an entertaining show only to draw in onlookers and serve them with a sales pitch for “miracle cures” and “cure-all elixirs.” While these shows may have been considered enjoyable—and for some, a source of hope—in the 1800s, the passing of legislation starting with the Pure Food and Drug Act in 1906 ultimately made the sale and peddling of misbranded drugs prohibited, so these performances could no longer exist in the same way.

Another example could be the popular minstrel shows that swept the nation throughout the 1800s and earlier part of the 1900s. These shows, many of which were performed in blackface makeup, depicted "comical" portrayals of racial stereotypes of African Americans. At the time, this was not only considered appropriate, but enjoyable and delightful. Today, any allusion to blackface is enough to destroy a brand’s reputation . Even Hemingway’s beloved circus has seen shifts in its “delightfulness” as questions around animal rights have challenged its practices in recent years.

Times change, and with them, so do our opinions of what might be considered entertaining—and the expense at which we’re willing to be entertained. Delight becomes nothing if not a product of day and age. Over the years, the changing aspects of traveling entertainment in America—the good, the bad, and the quirky—have reflected shifts in American values as much as they have reflected changes in technology, politics, and cultural norms.

To better paint the landscape of traveling entertainment throughout American history, Stacker compiled a list of 25 key moments using industry archives, historical accounts, and academic journals. From Barnum & Bailey to Annie Oakley, here’s a look at how traveling entertainment has evolved over the years.

1793: First circus in America

While traveling performers were hardly unheard of at this point, this was the first time that such entertainers were introduced to the country in the form of a circus as we know it today. The first circus came to be when an equestrian performer from England, John Bill Ricketts, created a Philadelphia-based spectacle that showcased riding acts, in addition to clown performances and tightrope walking.

The first performance, held on April 3, 1793, took place in a roofless arena that could hold 800 viewers. Ricketts later began touring with his circus company across the eastern U.S. and Canada, continuing until 1799, when a fire destroyed the pantheon and amphitheater he had built in Philadelphia to house his circus.

1820s: Traveling menageries move across the country

Though animal shows and exhibitions didn’t fully merge with the circus until the 1830s, this was a period when animals were considered an attraction in their own right. It mostly started when a New York farmer, Hachaliah Bailey, bought an African elephant from his brother , a sea captain who had purchased the animal at auction while abroad. Bailey began showing off his elephant to spectators for a small fee, which later inspired budding entrepreneurs to follow suit and acquire animals of their own to put on display and charge others to see. This rising trend gave way to a period of traveling menageries in the country.

1825: First tent circus in America

As the popularity of circuses began growing across the country, so did the reimagination of certain components of the show. In 1825, Joshua Purdy Brown became the first circus owner to move away from the wooden structure that housed most circuses. Instead, he replaced it with a large canvas tent , which was the first version of the traditional circus “big top.”

In 1832, Brown also became the first circus proprietor to officially roll a menagerie into his circus along with the more traditional acts and performances. Interestingly, the combination of the two—the circus and the menagerie—helped expand the audience of the former, which was often considered crude and frivolous and the time , by playing on the more widely accepted education value of the latter.

1833: The first wild animal training in an American circus

Just one year after Joshua Purdy Brown first combined his traveling circus with a traveling menagerie, there was another major leap in regards to animal exhibition. In 1833, animal trainer Isaac Van Amburgh became one of the country’s first famous lion tamers when he got into a cage with a lion, a tiger, and a leopard during a showcase in New York. Though animal training—and the taming of wild animals and large cats, in particular—became a critical part of the circus, Amburgh remains one of the earliest stars in the space and is even credited with being the first to perform the popular trick of sticking his head into a lion’s mouth .

1840s: The rise of the American freak show

In the mid-19th century, freak shows—exhibitions of oddities, absurdities, and “freaks” of all kinds—began gaining popularity in America. There had been smaller examples of these freak shows prior to this point, largely thanks to Chang and Eng, the original conjoined twins who came to America from Siam in 1829 and gave rise to the term “Siamese twins.” It was in the 1840s, though, that a rise in scientific and medical advancements made Americans particularly curious about the anomalies that seemed to be unexplainable. Thus, the freak shows took on a concurrently entertaining and scientific allure.

1842: P.T. Barnum opens Barnum’s American Museum

Another of the biggest reasons that freak shows gained popularity in the 1840s was P.T. Barnum. The American showman—who would found one of America’s most famous circuses, and was the inspiration behind the film “The Greatest Showman,” starring Hugh Jackman—saw an opportunity to double down on the popularity of spectating at oddities, absurdities, and scientifically unexplained deformities.

In 1842, he opened Barnum’s American Museum , which featured live animals—including the country’s first aquarium—alongside odd human spectacles, like a bearded lady and a 5-year-old dwarf named Tom Thumb who stood at 25 inches tall. In order to create a more sensational experience for museum visitors, Barnum often stretched the truth around the oddities in his museum to make them appear more mind-boggling. For example, Barnum told onlookers that Tom Thumb—whose name was actually Charles Stratton—was 11 years old rather than 5, to make his size seem even more dramatic for his age.

1844: Dan Rice is the king of clowns

A circus would be incomplete without its clowns, and the history of clowns would be incomplete without Dan Rice. The clown is remembered as one of the most notable in the history of circus performing—so much so, in fact, that his act including slapstick comedy and equestrian jesting had him at one point earning an outrageous-for-the-time $1000 per week . One of the signature characteristics of Rice’s act was his blending of silly humor with witty political satire.

1843: The Virginia Minstrels introduce the minstrel show

In the early 19th century, minstrel shows—humorous theatrical and musical performances that perpetuated problematic racial stereotypes—were gaining popularity. Shows would typically consist of white actors playing on stereotypes of African Americans, including impersonations of their singing and their dancing. In most cases, actors would don blackface makeup during their performances.

Thomas Dartmouth Rice—also known as Daddy Rice—is considered the father of blackface minstrelsy, as the actor mostly rose to fame following his 1928 performance of “Jump Jim Crow .” However, the tradition of blackface minstrelsy, which unfortunately carried well into the 20th century, gained most of its traction in 1843, when a quartet called the Virginia Minstrels had their first performance in New York .

1868: The British Blondes take America

Lydia Thompson was an English actress and singer who, in 1868, sailed to America with her troupe of performers, the British Blondes . The women began performing their famed burlesque shows in New York, combining musical performances and suggestive dancing with comedy. Though she didn’t invent burlesque—Americans had been familiar with the art form since around the 1840s—Thompson and her troupe are credited with spurring the rise in burlesque as a popular form of entertainment for audiences across the country.

1869: Completion of the transcontinental railroad

As traveling entertainment became an increasingly prominent fixture in America, it followed that advancements in transportation were critical to continued expansion, particularly for large operations like circuses. In 1869, the completion of the Transcontinental Railroad marked such a point. Suddenly, entertainers had an efficient, expansive mode of transportation that could transform how they traveled across the country. One of the first showmen to take advantage of the new railroad was Dan Castello, founder of Dan Castello’s Great Circus & Egyptian Caravan, who hopped aboard and traveled from Nebraska to California with two elephants and two camels in tow.

1871: The Greatest Show on Earth

While P.T. Barnum was seeing plenty of success with his museum of oddities, it wasn’t long before he was ready to take his show on the road. At first, that just consisted of Barnum bringing his oddities to others with “P.T. Barnum’s Grand Traveling American Museum.” In 1870, however, the showman was presented with an opportunity by two circus managers—W.C. Coup and his partner Dan Castello—to join forces and create a larger-than-life show. Barnum was excited about the prospect of combining his love for oddities with his interest in the traveling menageries and circus shows of the time. He accepted the offer and, together with Coup and Castello, the trio created "P.T. Barnum's Great Traveling Museum, Menagerie, Caravan, and Hippodrome,” later dubbed “The Greatest Show on Earth” because of its grandeur.

1877: “The Human Projectile”

Plenty of youngsters have attempted to recreate their own versions of a human cannonball while at the pool in the summer, but English aerialist Rossa Richter—better known by her stage name, “Zazel”—was the first true human cannonball to make her mark on the entertainment scene.

As a teenager, Zazel performed the first-ever cannonball stunt when she was catapulted out of a cannon-like contraption (created by William Leonard Hunt, a tightrope walker) towards a safety net. The spectacle gained thousands of fascinated onlookers as word spread about the performance, and Zazel ultimately made her way stateside from London to tour with P.T. Barnum’s circus, until an accident in 1891 put her out of commission.

1880: Barnum and Bailey’s Circus is born

By the 1880s, P.T. Barnum is doing pretty well for himself — but so was his primary competitor, James A. Bailey. While Bailey and his partner, James E. Cooper, spent the latter part of the 1870s traveling abroad with their circus, their eventual return to the U.S. posed a threat to Barnum, who ultimately joined forces with Bailey and Cooper to create the “Barnum & Bailey’s Circus.” This was the first major example of how the changing circus industry and the rise of heavy hitters in the space was giving rise to a monopolistic culture , whereby large railroad circuses were looking for ways to wipe out the competition, either through acquisition or mutually beneficial mergers.

1880s: Medicine shows begin mushrooming

While circuses and freak shows made their way around the country, they were joined by medicine shows in the 1880s. These shows consisted of performances that were typical of traveling musicians or circuses —e.g., vaudeville-style shows and magic tricks. The catch was that the performances were truly bait to pull audiences in and then eventually try to sell them “miracle cures” and “healing elixirs.” Often times, the performance put on by the troupe of performers would include something that could be used as a selling point for the products . For example, a “muscle man” routine might be used as a tool, by showcasing someone’s strength and then citing a particular elixir as the source of that strength.

1881: Magic lantern shows

Before motion pictures, there was the art of magic lantern shows. In these shows, traveling showmen would create visual experiences for onlookers by combining music and storytelling with hand-drawn illustrations that they’ve converted into slides. Joseph Boggs Beale—who worked as a traveling magic lantern showman for 39 years and is considered the country’s earliest screen artist—was known for bringing such stories and poems like “The Raven” to life on the screen.

1882: Ringling brothers perform vaudeville-style show

Before the five Ringling brothers started traveling together as a circus troupe in 1884, they spent a few years performing a vaudeville-style show, in which a couple of brothers would dance, two more would play their instruments, and the final brother would sing. In the two years between the start of their vaudeville performances and the launch of their circus, the Ringling brothers acquired a donkey and a Shetland pony , both of which were important to their first trick acts. These two years also saw the sixth and seventh Ringling brothers join the blossoming circus operation that eventually took off.

1883: Buffalo Bill’s Wild West Show begins

While some forms of traveling entertainment were just that—purely there for entertainment’s sake—other forms managed to entertain while offering a little bit of insight, even if dramatized, into a particular corner of American culture. That was the primary allure of Buffalo Bill’s Wild West Show —the audience could watch and get a glimpse into the world of the Wild West. The show, which was started in Nebraska by William F. Cody, debuted in 1883 and consisted of a wide array of performances, including sharpshooting demonstrations, rodeo events, races, and reenactments of key traditions or moments in the history of the Wild West (e.g., stagecoach robberies and buffalo hunting). Four years after starting his show, Cody took this taste of the Wild West to the east and performed for the first time in London in 1887.

1885: Annie Oakley joins Buffalo Bill

One of the major selling points of Buffalo Bill’s Wild West Show was the entirely unique set of characters and personalities in founder William F. Cody’s troupe, including cowboys and Native Americans, as well as animals like elk and bison. Amongst the characters in Cody’s troupe was Annie Oakley, the famous sharpshooter and entertainer. Oakley was a part of Buffalo Bill’s troupe for 17 years, during which time she wowed crowds with her precision—she could shoot a flame off a candle while it spun on a wheel .

1893: Chicago World Fair

Circuses and various forms of traveling entertainment had been present in America for a century at this point, but this was the time when carnivals, with their rides, games, and unique foodstuffs, came into play. While the primary purpose of the Chicago World Fair was to put some of the latest technological advancements on display, there was a small area of the event, called the Midway Plaisance, where free entertainment was offered. This included sideshows like a fortune teller and a fat lady, as well as try-your-luck games and a merry-go-round. The fair also featured the first Ferris wheel—built by George Washington Gale Ferris, Jr.—which was intended to be a one-up on Paris’s Eiffel Tower.

[Pictured: View of the Midway Plaisance at the World’s Columbian Exposition of 1893 including Ferris Wheel and captive balloon.]

1919: Barnum & Bailey join forces with Ringling Bros.

After achieving massive success stateside— the circus became a three-ring operation that was drawing in crowds of 10,000 and tackling a European tour—Barnum and Bailey’s Circus took a hit in 1906 when Bailey died. As the new behemoths on the block, the Ringling brothers decided to purchase Barnum and Bailey’s, with the plan to operate it separately from their original circus. That changed in 1919, when a temporary wartime consolidation of the two circuses proved incredibly profitable. Thus, the Ringling Bros. Barnum & Bailey Circus was born, and became the new Greatest Show on Earth.

1923: The birth of the auto thrill show

By the 1920s, Americans had become familiar with the wild stunts of the circus, and had gotten some tastes of thrill thanks to traveling carnivals. Recognizing the allure of that thrill —which he also knew well thanks to his family’s flight school—Ohio event promoter Ward Beam decided to create a new venture around this perceived trend. He went ahead and created what he called Ward Beam’s International Congress of Daredevils , which was a traveling troupe of daredevil automobilists who would take on challenges like nailing precision moves with their vehicles and racing or showing off a little speed. A big part of the shows was also the element of destruction. This first-of-its-kind auto thrill show set the stage for contemporary iterations, such as Monster Jam.

[Pictured: Auto racing legend Joie Chitwood Sr. developed a popular automotive thrill show that bore his name.]

1936: “The World’s Strangest Married Couple”

Another example of the kinds of “freaks” that might appear in a traditional American sideshow was “ the world’s strangest married couple .” Married in 1936, Al Tomaini and Bernice “Jeanie” Smith earned their moniker thanks to Tomaini’s sheer size—he was a “giant” who stood over 8 feet tall—and Jeanie’s half-sized (she was born with a birth defect that left her with only a torso and no legs). The couple spent several years touring the country with different circuses and carnivals, before actually running a few of their own.

1939: Founding of Amusements of America

The popularity of traveling carnivals following the Chicago World Fair in 1893 began to rise slowly in subsequent years, before a dramatic spike in the early 20th century. By 1905, about 22 years after the World Fair, there were 46 traveling carnivals in the country. By 1937, that number rose to approximately 300. Just a couple years after that estimate was reported, one of the most significant carnival companies in America’s history was created. In 1939, a man named Morris Vivona decided to buy the Ferris wheel from the New York World Fair, and, with that purchase, Amusements of America was born . The carnival operator set up temporary carnivals—complete with rides like the “giant wheel” and the “wave swinger”—that stretched across the eastern seaboard, as well as the Midwest. In 1995, Amusements of America was named the world’s largest traveling amusement park by “Guinness Book of World Records.”

[Pictured: An aerial view of the midway at a fair in Puyallup, Washington, in the 1930s.]

1948: The Viking Giant

Another example of a famous sideshow attraction, Jóhann Pétursson was a Goliath of a man who earned himself the nicknames “The Viking Giant” and “The Icelandic Giant” thanks to his height of 8 feet 8 inches. Pétursson originally participated in exhibitions around Europe before being invited to America by Ringling Bros. Barnum & Bailey Circus to join their show. Upon joining this circus, the Ringling brothers changed up Pétursson’s performance wear of choice—a top hat and a waistcoat—and instead had him dress in a traditional Viking costume, complete with the horned helmet.

2017: Ringling Bros. calls its final curtain

After a 146-year run, the Ringling Bros. and Barnum & Bailey Circus officially shut down in May of 2017. “The Greatest Show on Earth” had to call it quits after a combination of high operating costs and expensive legal battles made it difficult for the circus to stay afloat, let alone turn a profit. One of the biggest nails in the circus’ coffin was the pressure and legal action from animal rights groups, who opposed the use of animals in the show. Despite conceding to these pressures—Ringling Bros. officially stopped using elephants in their shows after May 2016—the iconic circus wasn’t able to revitalize ticket sales and revive itself after a few too many blows.

[Pictured: A group of Ringling Bros. performers waves goodbye to the elephants after their final performance in May 2016.]

Trending Now

50 best colleges on the east coast.

100 best 'SNL' episodes

50 most meaningful jobs in America

50 best crime TV shows of all time

America’s Big Circus Spectacular Has a Long and Cherished History

The “Greatest Show on Earth” enthralled small-town crowds and had a long-lasting influence on national culture

Janet M. Davis, Zócalo Public Square

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/8e/f6/8ef6cea3-f876-4c21-baea-559977c1e752/3b52556u-wr.jpg)

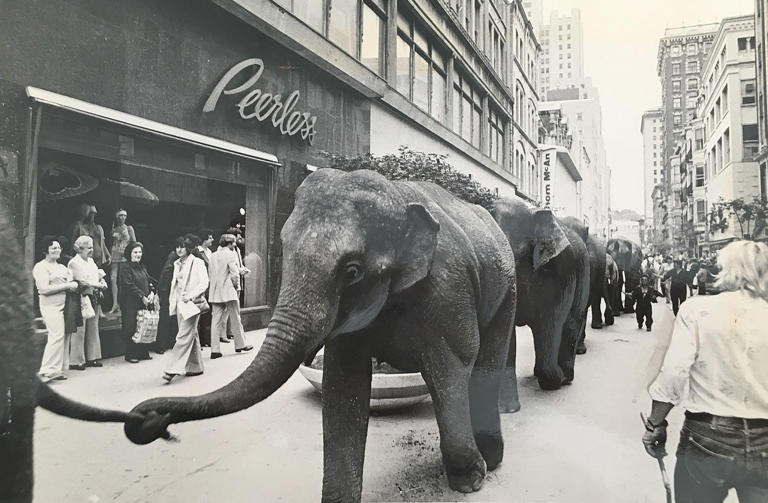

When Barnum and Bailey’s “Greatest Show on Earth” rolled into American towns in the 1880s, daily life abruptly stopped. Months before the show arrived, an advance team saturated the surrounding region with brilliantly colored lithographs of the extraordinary: elephants, bearded ladies, clowns, tigers, acrobats and trick riders.

On “Circus Day,” huge crowds gathered to observe the predawn arrival of “herds and droves” of camels, zebras, and other exotic animals—the spoils of European colonialism. Families witnessed the raising of a tented city across nine acres, and a morning parade that made its way down Main Street, advertising the circus as a wondrous array of captivating performers and beasts from around the world.

For isolated American audiences, the sprawling circus collapsed the entire globe into a pungent, thrilling, educational sensorium of sound, smell and color, right outside their doorsteps. What townspeople couldn't have recognized, however, was that their beloved Big Top was also fast becoming a projection of American culture and power. The American three-ring circus came of age at precisely the same historical moment as the U.S. itself.

Three-ring circuses like Barnum and Bailey's were a product of the same Gilded Age historical forces that transformed a fledgling new republic into a modern industrial society and rising world power. The extraordinary success of the giant three-ring circus gave rise to other forms of exportable American giantism, such as amusement parks, department stores, and shopping malls.

The first circuses in America were European—and small. Although circus arts are ancient and transnational in origin, the modern circus was born in England during the 1770s when Philip Astley, a cavalryman and veteran of the Seven Years War (1756-1763), brought circus elements—acrobatics, riding, and clowning—together in a ring at his riding school near Westminster Bridge in London.

One of Astley’s students trained a young Scotsman named John Bill Ricketts , who brought the circus to America. In April of 1793, some 800 spectators crowded inside a walled, open-air, wooden ring in Philadelphia to watch the nation’s first circus performance. Ricketts, a trick rider, and his multicultural troupe of a clown, an acrobat, a rope-walker, and a boy equestrian, dazzled President George Washington and other audience members with athletic feats and verbal jousting.

Individual performers had toured North America for decades, but this event marked the first coordinated performance in a ring encircled by an audience. Circuses in Europe appeared in established urban theater buildings, but Ricketts had been forced to build his own wooden arenas because American cities along the Eastern Seaboard had no entertainment infrastructure. Roads were so rough that Ricketts' troupe often traveled by boat. They performed for weeks at a single city to recoup the costs of construction. Fire was a constant threat due to careless smokers and wooden foot stoves. Soon facing fierce competition from other European circuses hoping to supplant his success in America, Ricketts sailed for the Caribbean in 1800. While returning to England at the end of the season, he was lost at sea.

After the War of 1812, American-born impresarios began to dominate the business. In 1825, Joshua Purdy Brown, a showman born in Somers, New York, put a distinctly American stamp on the circus. In the midst of the evangelical Second Great Awakening (1790-1840), an era of religious revivalism and social reform, city leaders in Wilmington, Delaware banned public amusements from the city. Brown stumbled upon the prohibition during his tour and had to think fast to outwit local authorities, so he erected a canvas “pavilion circus” just outside the city limits.

Brown’s adoption of the canvas tent revolutionized the American circus , cementing its identity as an itinerant form of entertainment. Capital expenses for tenting equipment and labor forced constant movement, which gave rise to the uniquely American one-day stand. On the frontier edges of society, entertainment-starved residents flocked to the tented circus, which plodded by horse, wagon, and boat, pushing westward and southward as the nation’s borders expanded.

The railroad was the single most important catalyst for making the circus truly American. Just weeks after the completion of the Transcontinental Railroad in May 1869, Wisconsin showman Dan Castello took his circus—including two elephants and two camels—from Omaha to California on the new railroad. Traveling seamlessly on newly standardized track and gauge, his season was immensely profitable.

P.T. Barnum , already a veteran amusement proprietor, recognized opportunity when he saw it. He had set a bar for giantism when he entered the circus business in 1871, staging a 100-wagon “Grand Traveling Museum, Menagerie, Caravan, and Circus.” The very next year, Barnum’s sprawling circus took to the rails. His partner William Cameron Coup designed a new flatcar and wagon system which allowed laborers to roll fully loaded wagons on and off the train.

Barnum and Coup were outrageously successful, and their innovations pushed the American circus firmly into the combative scrum of Gilded Age capitalism. Before long, size and novelty determined a show’s salability. Rival showmen quickly copied Barnum’s methods. Competition was fierce. Advance teams posting lithographs for competing shows occasionally erupted in brawls when their paths crossed.

In 1879, James A. Bailey, whose circus was fresh off a two-year tour of Australia, New Zealand, and South America, scooped Barnum when one of his elephants became the first to give birth in captivity at his show’s winter quarters in Philadelphia. Barnum was begrudgingly impressed—and the rivals merged their operations at the end of 1880. Like other big businesses during the Gilded Age, the largest railroad shows were always prowling to purchase other circuses.

Railroad showmen embraced popular Horatio Alger “rags-to-riches” mythologies of American upward mobility. They used their own spectacular ascent to advertise the moral character of their shows. Bailey had been orphaned at eight, and had run away with a circus in 1860 at the age of 13 to escape his abusive older sister. The five Ringling brothers, whose circus skyrocketed from a puny winter concert hall show in the early 1880s to the world’s largest railroad circus in 1907, were born poor to an itinerant harness maker and spent their childhood eking out a living throughout the Upper Midwest.

These self-made American impresarios built an American cultural institution that became the nation’s most popular family amusement. Barnum and Bailey's big top grew to accommodate three rings, two stages, an outer hippodrome track for chariot races, and an audience of 10,000. Afternoon and evening performances showcased new technologies such as electricity, safety bicycles, automobiles, and film; they included reenactments of current events, such as the building of the Panama Canal.

By the end of the century, circuses had entertained and educated millions of consumers about the wider world, and employed over a thousand people. Their moment had come. In late 1897, Bailey took his giant Americanized circus to Europe for a five-year tour, just as the U.S. was coming into its own as a mature industrial powerhouse and mass cultural exporter.

Bailey transported the entire three-ring behemoth to England by ship. The parade alone dazzled European audiences so thoroughly that many went home afterwards mistakenly thinking they had seen the entire show. In Germany, the Kaiser’s army followed the circus to learn its efficient methods for moving thousands of people, animals, and supplies. Bailey included patriotic spectacles reenacting key battle scenes from the Spanish-American War in a jingoistic advertisement of America’s rising global status.

Bailey’s European tour was a spectacular success, but his personal triumph was fleeting. He returned to the United States in 1902 only to discover that the upstart Ringling Brothers now controlled the American circus market.

When Bailey died unexpectedly in 1906, and the Panic of 1907 sent financial markets crashing shortly thereafter, the Ringlings were able to buy his entire circus for less than $500,000. They ran the two circuses separately until federal restrictions during World War I limited the number of railroad engines they could use. Thinking the war would continue for many years, the Ringlings decided to consolidate the circuses temporarily for the 1919 season to meet federal wartime regulations.

The combined show made so much money that the Ringling Bros. and Barnum & Bailey’s Circus became permanent—known as "The Greatest Show on Earth"—until earlier this year, when, after 146 years, it announced it would close .

The Smithsonian Folklife Festival celebrates its 50th anniversary this year with an exploration of the life and work of circus people today. "Circus Arts" performances, food and workshops take place on the National Mall in Washington, D.C., June 29 to July 4 and July 6 to July 9.

Janet M. Davis teaches American Studies and History at the University of Texas at Austin. She is the author of The Gospel of Kindness: Animal Welfare and the Making of Modern America (2016); The Circus Age: American Culture and Society Under the Big Top (2002); and editor of Circus Queen and Tinker Bell: The Life of Tiny Kline (2008).

Get the latest History stories in your inbox?

Click to visit our Privacy Statement .

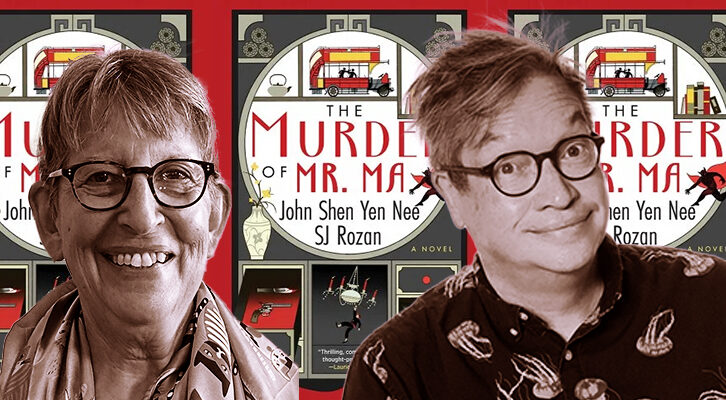

- Reading Lists

- New Nonfiction

- Awards/Festivals

- Daily Thrill

- Noir/Hardboiled

- Espionage/Thriller

- Legal/Procedural

- Literary Hub

A Brief History of Circus in Fiction

Melanie golding on the allure of circus life and its unforgettable characters..

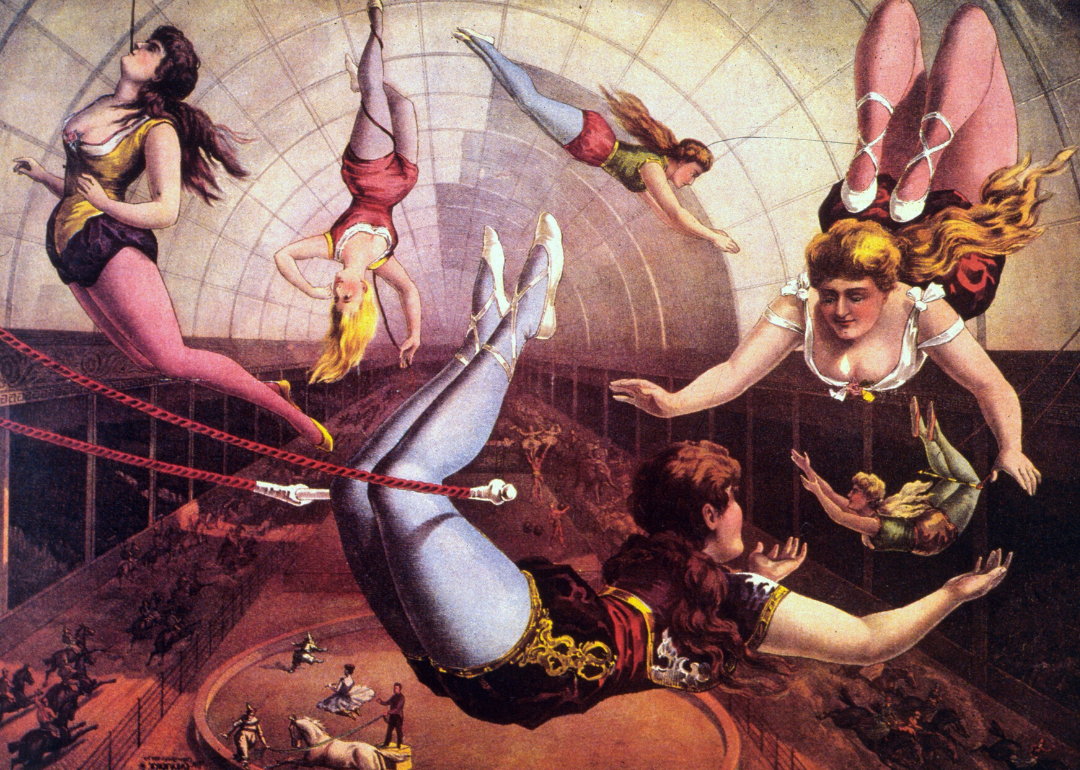

The history of travelling carnivals, or circuses, is complex. The form is steeped in tradition, but the people who live and make their living in modern circuses are a diverse bunch, hailing from everywhere in the world. Often they live a nomadic life, travelling internationally with different circuses each season. There are circus families that go back generations, but there are also circus stars who had no more connection to the circus as children than an annual family visit. That tiny window into this world is sometimes enough; magical enough and tantalising enough to make you dedicate your entire existence to it. Circus can be in the blood in more than one way. It can be craved, and sought, and found. Novelists like myself are rarely nomadic, or dare I say it, particularly acrobatic, except in our minds. That is where we chase our dreams: in reading and writing of lives we are perhaps not brave enough to seek out for ourselves.

‘Circus’ in Ancient Rome referred to a circular arena where chariot racing took place, but most sources agree that the form most modern circuses take, specifically groups of travelling artists under the same Big Top, where clowns entertain, jugglers and acrobats perform and animal tricks are shown, probably began in the eighteenth century. Circus has evolved over time, and these days parts of traditional circus, for example ‘freak’ shows, while no longer deemed acceptable as entertainment still fascinate readers of historical fiction. The concept of circus is therefore multi-layered, slippery, romantic and taboo. It evokes nostalgia, excitement, mystery and magic, but doesn’t lend itself easily to a strict definition. Those shows that have survived to this day are each of them different, from the towering spectacle of the Moscow State circus to the charm, skill and artistry of Gifford’s. The shifting nature of circus is reflected in its presence in the public consciousness. It’s ephemeral, somehow unreal, perhaps an illusion. Unless, that is, you live in one.

Today, running away to the circus may seem like an impossible dream, but it’s one that is still achievable if you know where to look, if you have the vision and talent, if you hear its siren call. Novelists hear it. We are drawn to the darkness, the mystery, the magic and the illusion; the gaps where fiction, and imagination, can allow our minds to soar at an impossible height, to take that leap into the unknown, to a place where anything might be possible.

Something Wicked This Way Comes : Ray Bradbury, 1962

Bradbury’s dark fantasy horror uses the carnival to explore themes of transition to adulthood. This coming-of-age tale is heavy with nostalgia, the terrifying possibilities of the magic carousel representing only a small part of the powers of transformation this dark carnival can wield. Bradbury’s tale itself is transformational, inspiring novelists to this day as a masterclass of the form.

Nights at the Circus : Angela Carter, 1984

Carter incorporates postmodernism, magical realism and feminist themes into this award winning, playful, original and complex novel. The story includes a travelling circus, a girl hatched from an egg who grows wings, a fortune telling pig and a band of outlaws. Its influence on culture is wide-ranging, featuring as it does many expertly-drawn oddities and weaving motifs. This novel is her penultimate, and in the years since its publication has received much attention and analysis due to its many ground-breaking attributes. Carter always merits a re-read. I learn something new every time I pick up one of hers.

Geek Love : Katherine Dunn, 1989

While Geek Love is set in a travelling circus, the freakshow elements are front and centre. Characters are spectacles in themselves, most of them bred for the freakshow, most of them as twisted inside as they are out. There are cults, and strippers, and a character conceived using telekinetic sperm. What more could you wish for? Transporting, entertaining, genious.

Water for Elephants : Sarah Gruen, 2006

Gruen’s circus train is a cruel place, where workers are ‘red-lighted’ for perceived slights by being thrown from a moving train. The protagonist, Jacob (with echoes of his biblical namesake) abandons his life as a veterinary student to board the train, where his skills are put to use with the circus animals. This colourful novel contains forbidden love, high-speed train-car hopping, and an elephant stampede.

The Night Circus : Erin Morgenstern, 2011

Utterly enchanting, dark and magical fantasy novel. In it, the Circus of Dreams exists only in the night, and is powered by real magic. Its sideshows include fortune tellers and acts which defy the laws of gravity and physics, but its function is also to serve as the showground for a fight-to-the-death competition between the proteges of two powerful magicians. I loved this novel and didn’t want it to end.

Joyland , Stephen King, 2013

King’s novel features an amusement park, not a circus, but the nostalgia and magic I look for in a circus novel are present here. Both a murder mystery and a ghost story, Joyland depicts the vividness of carnival life alongside darker and more supernatural themes. The setting here is woven with the plot, the two sitting naturally together with the ephemerality and atmosphere of the funfair, and all that has to offer a writer. Safety in place like this may well be nothing more than an illusion.

Station Eleven : 2014, Emily St John Mandel

Following a deadly pandemic, the Travelling Symphony finds meaning in life through their art and community. I read this almost-perfect novel when it came out, and I still hold that world inside my head. If you are yet to read this book, I envy you.

The Museum of Extraordinary Things : Alice Hoffman, 2014

Set in Coney Island in 1911, the ‘museum’ of the title is another freak show, with Coralie as a mermaid. Despite ourselves, we are endlessly fascinated with freak shows, though as an author I identify more with those defined as ‘freaks’ than those actual freaks who see these characters as anything less than human. Coralie falls in love with another runaway, another depiction of a displaced person, shunned because of what they are rather than who they are. Which is what all the best stories are about, right?

Circus of Wonders : Elizabeth MacNeal, 2021

MacNeal weaves together themes and characters containing sparks of all that has gone before, creating originality while nodding to inspiration. Perhaps a coincidence that Nell shares her name with the late Nell Gifford, an equestrianist who started Gifford’s circus and ran it until her death in 2021. MacNeal’s Nell’s wings are reflected in Carter; forbidden love is here, too, as well as the freakshow we cannot turn away from. Masterful, magical, ingenious novel. I urge you to read it immediately.

- Share on Facebook (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Twitter (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Google+ (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on LinkedIn (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Reddit (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Tumblr (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Pinterest (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Pocket (Opens in new window)

Melanie Golding

Previous article, next article, get the crime reads brief, get our “here’s to crime” tote.

Popular Posts

CrimeReads on Twitter

Sean Howe on High Times Magazine and Its Enigmatic, Larger-than-Life Editor

Advertisers: Contact Us

Privacy Policy

- RSS - Posts

Support CrimeReads - Become a Member

CrimeReads needs your help. The mystery world is vast, and we need your support to cover it the way it deserves. With your contribution, you'll gain access to exclusive newsletters, editors' recommendations, early book giveaways, and our new "Well, Here's to Crime" tote bag.

Become a member for as low as $5/month

RI’s curious history with traveling circuses as Ringling Bros. and Barnum & Bailey returns

PROVIDENCE – The circus is coming to town.

After a six-year hiatus, Ringling Bros. and Barnum & Bailey is bringing its traveling show back to Providence’s Amica Mutual Pavilion this weekend. The last time the circus came to town was also its last performance before folding its tent for five years and relaunching as a reimagined show last year.

This weekend’s shows promise an “immersive environment” with new technology. Of course, the acrobats, clowns, extreme BMX riders, trapeze artists and teeter-totters will be there. So will 20-year-old Skyler Miser, " Human Rocket ," who will fly 110 feet through the air above the audience after being shot from a cannon.

Rhode Island is no stranger to circus visits, but it has a complicated relationship with the traveling shows. Here are a few curious facts from the Ocean State’s circus history.

Rhode Island was the first state to ban bullhooks

Rhode Island has a soft spot for exotic animals. For evidence of this, look no further than the amusing tale of 11 escaped monkeys who wreaked havoc and captured hearts in Warwick in the late 1930s.

Perhaps because of this, it may be no surprise that Rhode Island became the first state in the U.S. to ban bullhooks. Also known as an elephant goad, a bullhook is a long rod fitted with a hook and a sharp metal tip. Trainers and animal keepers have used them to poke elephants in sensitive areas, according to Elephant Voices, a nonprofit. The practice drew sharp criticism from human rights advocates, who said it caused physical and psychological damage to the elephants.

Rhode Island happened to be the last place where Ringling Bros. and Barnum & Bailey included elephants as part of the show. The circus retired its elephant act about a month before Rhode Island banned the use of the devices in the state.

No exotic animals, please

Some Rhode Islanders love exotic animals so much that they have determined to keep them out, if possible. Last December, the Providence City Council approved an ordinance – later signed by Mayor Brett Smiley – prohibiting shows that use wild or exotic animals.

“It shall be unlawful for any person or organization to conduct, sponsor, walk, exhibit or operate a traveling show or circus that includes live wild or exotic animals on any public or private land within the City of Providence,” the ordinance says, though it makes exceptions for educational purposes and domestic animals.

Ringling Bros. and Barnum & Bailey has phased out all animals from its shows. Instead, the circus now travels with a robotic dog that performs tricks with a trainer.

A near-fatal accident leaves aerialists severely injured

The most dramatic moment in the circus history of Rhode Island was also the most tragic. On May 4, 2014, eight acrobats, tethered by their hair to a chandelier-like contraption more than 20 feet in the air, plummeted to the floor during a live performance of Ringling Bros. and Barnum & Bailey. They broke bones and suffered internal and spinal injuries.

The accident resulted in a lawsuit against the Rhode Island Convention Center Authority and its managing company. It was settled six years later, in 2020, for $52.5 million.

A look back: After a harrowing plunge toward death, circus aerialists rise back to life

The road to recovery was not easy. It was full of tears and setbacks. But one by one the former performers carved lives for themselves out of the wreckage of the accident.

"You need to fight for your life," said Widny Neves, one of the survivors. "You need to fight for something even better. You need to see that beyond that big, dark tunnel, there's light at the end. There is light.”

This article originally appeared on The Providence Journal: RI’s curious history with traveling circuses as Ringling Bros. and Barnum & Bailey returns

Cookies on GOV.UK

We use some essential cookies to make this website work.

We’d like to set additional cookies to understand how you use GOV.UK, remember your settings and improve government services.

We also use cookies set by other sites to help us deliver content from their services.

You have accepted additional cookies. You can change your cookie settings at any time.

You have rejected additional cookies. You can change your cookie settings at any time.

- Environment

- Wildlife, animals, biodiversity and ecosystems

- Animal welfare

Travelling circuses: wild animal performance and exhibition

Wild animals cannot be exhibited or used in a performance as part of a travelling circus in England.

Applies to England

- Guidance for Scotland

Under the Wild Animals in Circuses Act 2019 , you must not exhibit wild animals or use them in a performance as part of a travelling circus in England.

You could get an unlimited fine and a criminal record for allowing wild animals to perform or be exhibited in a travelling circus.

Definition of wild animal

A wild animal is any species not commonly domesticated in Great Britain, including:

- big cats, like lions and tigers

The definition of wild animal for this act does not include commonly domesticated species such as dogs, cats, horses, rabbits, pigeons or doves.

See page 29 of the Zoo Licensing Act guide for more information about species that may be classed as wild animals.

Definition of a travelling circus

A travelling circus is a circus which travels from one location to another, regularly or not, to provide entertainment. It can still be considered a travelling circus if it is not moving around frequently, for example where the circus remains in one place after the touring season has finished.

The word ‘circus’ does not need to be in the name.

A circus permanently located at one single site with fixed buildings and structures is a static circus and not covered by this law. However, the rules for wild animals will apply to a static circus if it:

- sends some or all of its acts to put on a circus show anywhere other than its official location

- permanently relocates several times

Prevent the public viewing your wild animals

If you’re the owner or manager of a travelling circus with wild animals, you must make every effort to prevent the public viewing the animals.

You may travel with your animals, but you must not:

- allow the public to view wild animals carrying out tricks or manoeuvres

- allow the public to see wild animals while the circus is performing or before a show when the public are allowed on the site

- house, keep or transport wild animals in a way that encourages viewing by the public or promotes the circus

- use wild animals in displays, photo opportunities, parades and animal rides

- use imagery or footage of wild animals to promote your activities, including on printed materials, websites and social media

These rules apply even if you are not asking for payment or a donation.

You would however not commit an offence, for example, if the public saw a wild animal grazing in a paddock if you’d made no active effort to encourage viewing, or promote the circus.

Permitted wild animal performances or exhibitions

Animal performances or exhibitions which do not form part of a circus or are not used to promote a circus, are not included in this ban. This includes:

- bird of prey displays

- festive reindeer displays

- school or educational visit

- animal encounters and handling sessions or parties

- animals used for television, film or advertisements

- zoo and safari park outreach activities

- mobile animal exhibits

Transporting wild animals

Travelling circuses are still allowed to transport wild animals while they are in England.

For example, you can transport wild animals:

- for veterinary treatment or for re-homing

- as part of a travelling circus passing through England on tour but not used in performance or exhibited

- considered as pets and transported with the travelling circus

Read guidance on the welfare of animals during transport .

Protect animal welfare

If you choose to keep wild animals with your travelling circus, you must continue to comply with animal welfare and public safety regulations.

Read guidance on animal welfare , and check if you need to apply for a licence to keep a wild animal .

Inspections

An inspector appointed by the Department for Environment, Food and Rural Affairs (Defra) may inspect your travelling circus to check that you do not have wild animals performing or being exhibited.

You could get an unlimited fine if you do not assist or you intentionally obstruct an inspector.

The inspector can bring up to 2 other people with them to help with their inspection. These can include a police constable or a person from the local animal health office.

An inspector must show identification and explain why they are carrying out an inspection. They can bring appropriate equipment and materials with them.

If they’re entering under a warrant, they must produce a copy of the warrant and leave a copy with either the person in charge or on the premises.

An inspector can seize any item, other than a wild animal, if it helps to prove that you or your circus has committed an offence.

Report complaints

If you have concerns that a travelling circus is exhibiting wild animals or using them in a performance, you should email your complaint to Defra at [email protected] .

Added email address for reporting complaints.

First published.

Related content

Is this page useful.

- Yes this page is useful

- No this page is not useful

Help us improve GOV.UK

Don’t include personal or financial information like your National Insurance number or credit card details.

To help us improve GOV.UK, we’d like to know more about your visit today. We’ll send you a link to a feedback form. It will take only 2 minutes to fill in. Don’t worry we won’t send you spam or share your email address with anyone.

- Skip to main content

- Accessibility help

Information

We use cookies to collect anonymous data to help us improve your site browsing experience.

Click 'Accept all cookies' to agree to all cookies that collect anonymous data. To only allow the cookies that make the site work, click 'Use essential cookies only.' Visit 'Set cookie preferences' to control specific cookies.

Your cookie preferences have been saved. You can change your cookie settings at any time.

Wild Animals in Travelling Circuses (Scotland) Act 2018: guidance

Guidance notes for the Wild Animals in Travelling Circuses (Scotland) Act 2018.

3. The purpose of the Act is to make it an offence to use (for performance, display, or exhibition) wild animals in travelling circuses in Scotland and to allow for the enforcement of that ban. It applies to Scotland only.

4. A detailed explanation of the policy intentions underpinning the Act's purpose can be found in the Policy Memorandum [1] that accompanied the Bill.

5. Section 1 of the Act makes it an offence for circus operators to use, or to cause or permit another person to use, wild animals in a travelling circus.

6. An offence is committed in relation to a travelling circus only if the wild animal is transported to a place where it is used in the travelling circus. It does not matter whether that transportation takes place along with the rest of the circus while it travels, or whether it takes place under separate arrangements that the travelling circus may have made. For example, the travelling circus may contract with an independent carrier to move its wild animals, or may arrange for wild animals it does not own to be transported to the various venues at which it gives performances.

7. Wild animals may continue to be kept by travelling circuses whilst in Scotland, so long as they are not used. This may be as pets owned by individual circus workers and kept in their domestic residences. Alternatively, there may be retired wild animals still living and travelling with the circus, or working animals, used outside of Scotland, which come to Scotland during the closed season to overwinter. 8. In some situations the keeping of such animals may be subject to other legislative requirements, e.g. the Dangerous Wild Animals Act 1976.

9. Wild animals may also continue to be transported by travelling circuses whilst in Scotland, so long as they are not used in Scotland. For example, wild animals kept as pets may be transported with the travelling circus, and wild animals may be transported for veterinary treatment or for re-homing, or may be part of a travelling circus passing through Scotland on their tour but are not used in Scotland.

10. In all these cases, provided there is no use of a wild animal in a travelling circus, no offence is committed under the Act. However, other legislation may apply. The welfare of these animals continues to be protected by the Animal Health and Welfare (Scotland) Act 2006 while they are in Scotland.

Meaning of "use"

11. Section 1(3) of the Act states that a wild animal is used if the animal performs or is displayed or exhibited.

12. "Performance" would include, but is not limited to, tricks or manoeuvres viewed by the public. The "exhibition" of a wild animal includes being proactively or deliberately housed or shown in a way that encourages viewing by the public, for example by the use of signage delivering information to the public. "Display" includes, but is not limited to, use in parades, or deliberate positioning of wild animals to facilitate or encourage viewing, for example in fields next to public rights of way in a manner calculated to promote the circus, or next to a circus poster, or whilst dressed in any performance regalia. An offence is committed whether or not payment is required, or a donation suggested, in order to view the performance, exhibition, or display.

13. The public have rights of access under statutory Scottish land access rights and it is difficult to remove wild animals in travelling circuses entirely from view without potentially compromising their welfare. Circus operators would not have committed an offence if, for example, a member of the public viewed a wild animal grazing unadorned in a paddock where there was no active effort on the part of the travelling circus to encourage that viewing.

Meaning of "wild animal"

14. Section 2(1) of the Act states that a wild animal is an animal other than one which is of a kind that is commonly domesticated in the British Islands.

15. Section 2(2) of the Act states that for the purpose of subsection (1), an animal is of a kind that is domesticated if the behaviour, life cycle or physiology of animals of that kind has been altered as a result of the breeding or living conditions of multiple generations of animals of that kind being under human control.

Tame vs domesticated

16. The fact that an individual animal, of a kind that would normally be considered wild, has been "tamed" does not mean it falls outwith the definition of wild animal above. In circuses, wild animals will most likely be "tamed" and may have been bred for a number of generations within a circus environment. However, domestication is a genetic selection process across a significant population of animals for specific traits (for example, milk production in cattle, muscle mass in turkeys, good herding skills in dogs), over more than just a few generations. This selection process results in clear physical and behavioural changes from the original wild-type.

17. It is recognised that some wild circus animals come from a number of generations of animals bred in circuses and the behaviour that they exhibit may be different to animals in the wild. However, breeding for circus use began much more recently, takes place in a relatively small population, and has not resulted in any significant genetic, physiological or life-cycle change. There is also no change to the instinctive behaviours of such animals, although individual animals may be prevented from expressing instinctive behaviours and trained to exhibit behaviours unnatural to them. Individual or groups of "tame" wild circus animals are still wild animals, in terms of the relevant definitions, for the purposes of the Act.

A kind of animal

18. The definitions of both 'wild animal' and 'domesticated' specifically use the phrase animals of a kind , making it clear that whether an animal is considered wild or domesticated is not decided at the level of an individual animal or group of animals; it is considered at the much wider level of the kind of animal. When considering whether or not an offence has been committed, it is necessary to consider what kind of animal is being used by a travelling circus.

19. For example, if a travelling circus uses a group of bears, the question to be answered in terms of the Act is whether that kind of animal, i.e. "bears" as a kind of animal, are commonly domesticated in the British Islands. The question is not whether the individual animals in that specific group of bears owned by the travelling circus are domesticated, as that specific group of bears is not a separate "kind" of animal. The circus bears are all bears in terms of the "kind" of animal they are.

Commonly domesticated in the British Islands

20. In order for a kind of animal not to be considered wild for the purpose of the Act, it must be commonly domesticated in the British Islands.

21. Some kinds of circus animals may be considered domesticated in their country of origin but are not currently commonly domesticated in the British Islands, perhaps only being kept in Scotland in zoos or wildlife parks. For example, in their countries of origin camels have been used for many thousands of years by man and have been adapted for such use through breeding to favour certain traits. Although this kind of animal is kept in the UK , the majority are kept in a manner that does not involve on-going domestication. Therefore, camels are a kind of animal which is not commonly domesticated in the British Islands, at the time of writing. Zoos and wildlife parks generally aim to maintain genetically diverse collections – they do not normally continue genetic selection for the purpose for which an animal may have been domesticated in their country of origin.

22. This contrasts with the position of llamas. Llamas have long been domesticated in South America; they have been widely used as a meat and pack animal by Andean cultures for many centuries. This kind of animal is now widely found in the British Islands in a farming environment where there is on-going genetic selection to suit agricultural needs. Hence this kind of animal is commonly domesticated in the British Islands.

In cases of doubt

23. It is possible that wild species, or species domesticated in other countries, will in future become commonly domesticated in the British Islands due to changing prevalence and use. If there are future cases where there are uncertain or conflicting views regarding whether a kind of animal is to be considered wild for the purposes of the Act, the Scottish Ministers may, by regulations, specify whether a particular kind of animal is or is not wild. However the power to make regulations is without prejudice to the generality of the definition of wild animal in section 2 of the Act. Additionally, this power does not require Scottish Ministers to list, in legislation, all wild animals.

Meaning of "circus"

24. The word 'circus' is not defined in the Act and therefore relies on an ordinary interpretation of the word.

Ordinary meaning

25. The term circus is generally understood to mean a company of performers who put on shows with diverse entertainments, often of a daring or exciting nature, that may include, for example, acts such as a ringmaster, clowns, acrobats, trapeze acts, hoopers, tightrope walkers, jugglers, unicyclists, as well as other stunt-oriented or similar acts. A circus may or may not include animals of the domesticated and/or wild type.

26. The intended role of the wild animals, if present, is generally to provide spectacle, entertainment and/or as a way of demonstrating the skill and/or dominance of the trainer. Their effectiveness in this may be enhanced through the use of colourful trappings, costumes or props. The displays or performances of the wild animals often demonstrate unnatural tricks, manoeuvres or behaviours primarily for the purpose of amusement or entertainment rather than education (although the educational role of performances is considered further below). These acts often, although not exclusively, take place in a circular arena, tented environment or similar environment, or a brightly coloured or themed environment.

27. The presence or absence of such characteristics may assist in assessing whether or not an undertaking, act, entertainment or similar thing is or is not a circus. However, the inclusion or omission of any particular characteristic will not be decisive, and the presence or absence of these characteristics will need to be balanced against other aspects of the undertaking, act, entertainment or similar thing in each individual case.

Self-identification/Substance

28. A type of undertaking, act, entertainment or similar thing may self-identify as a "circus" either in its name or through application for recognition under legislative regimes that govern circuses in other national territories, for example the Welfare of Wild Animals in Travelling Circuses (England) Regulations 2012. However, a type of undertaking, act, entertainment or similar thing may fall within the ordinary meaning of "circus" even if it does not use the word "circus" in its advertising material. What is relevant is the substance of the show, not its title - a mere change in name of a show would not render it outwith the ordinary meaning of circus if in fact the substance of the show is a circus like performance which falls inside what would be considered to be the ordinary meaning of circus.

Educational role

29. The fact that a particular performance, display or exhibition of a wild animal may include an educational aspect would not render that performance, display or exhibition outwith the ordinary meaning of circus, if the substance of the show is falls within that ordinary meaning.

30. The following are examples of types of undertakings, acts, entertainment or similar things which would generally not be considered to fall within the ordinary meaning of circus;-

- Bird of prey displays

- Festive reindeer displays ( i.e. the use of reindeer in a Christmas fair or similar festive entertainment)

- School/educational visits

- Animal handling sessions or parties, normally but not exclusively involving children

- Animals used for television, film or advertisements, from pre-production to post-production

- Community celebrations such as local gala days

- Zoo and safari park outreach activities

Meaning of "travelling circus"

31. Section 3 provides that a "travelling circus" means a circus which travels, whether regularly or irregularly, from one place to another for the purpose of providing entertainment. "Travelling circus" includes: a circus which travels in the above way for the purpose of providing entertainment, despite there being periods during which it does not travel from one place to another; and any place where a wild animal associated with such a circus is kept (including temporarily). It does not include, for example, a circus which travels in order to relocate to a new fixed base for use only or mainly as a place to give performances.

32. As set out above, section 3 provides the meaning of "travelling circus" and states that it means a circus which travels, whether regularly or irregularly, from one place to another for the purpose of providing entertainment.

33. Traditional travelling circuses that involve a nomadic lifestyle with performances at a number of locations on a tour fall within this definition. The following types of undertakings, acts, entertainments or similar things are examples which are unlikely to fall within the definition of travelling circus in the Act: travelling bird of prey demonstrations, screen production, touring TV or film productions, mobile displays from zoos, educational road-shows, and reindeer displays including festive displays. Even though they may travel regularly or irregularly from one place to another they do not fall within the ordinary interpretation of circus and do not meet the definition of "travelling circus" in the Act.

34. A travelling circus remains a travelling circus even during periods when it is not travelling (for example during temporary tour stops or during the winter closed season). The expression "travelling circus" also includes any place where a wild animal associated with such a circus is kept, including temporarily, such as a wild animal's accommodation. The effect of this is that if a travelling circus wild animal is, for example, actively exhibited or actively displayed while it is in any kind of accommodation, at any time, it is an offence under section 1 of the Act.

35. This includes while wild animals are being overwintered (the housing of circus animals over the circus closed season, which is generally over the winter). Any active display or performance of a wild animal being kept in these overwintering circumstances would be an offence. It would not be an offence, however, for wild animals on loan from a travelling circus (or indeed from a static circus, to which the Act does not apply in the first instance) to be used in TV or film production or festive displays in Scotland, since they are not being used in a travelling circus.

36. Where a permanently located (static) circus sends out either all or a subset of their acts to put on shows at places other than at its fixed base, these acts may also fall under the definition of a travelling circus if they are travelling, regularly or irregularly, from one place to another for the purpose of providing entertainment. The use of any wild animals in such cases would need to be carefully considered as it may constitute an offence. However, where a permanently located (static) circus business chooses to relocate to another permanent / static site and subsequently uses wild animals in its show at its new permanent site, no offence is committed since the business is still considered to be a static circus, not a travelling circus. In that case the static circus travels from one place to another place for the purpose of relocation to a permanent fixed performance base.

37. It is possible that there may be cases where there are uncertain or conflicting views regarding whether a type of undertaking, act, entertainment or similar thing is or is not regarded as a travelling circus for the purposes of the Act. Scottish Ministers may specify, by regulations, whether a particular type of undertaking, act, entertainment or similar thing is or is not a travelling circus. However the power to make regulations is subject to the generality of the definition of travelling circus in section 3 of the Act. In addition, the power does not require the Scottish Ministers to list, in legislation, all undertakings, acts, forms of entertainment or other similar things to be regarded as a travelling circus.

Meaning of "circus operator"

38. Any person who is a circus operator commits the offence in section 1 of the Act if that person uses, or causes or permits another person to use, a wild animal in a travelling circus.

39. Section 3 of the Act defines a circus operator as:

- Circus owners

- People who do not own a circus but have overall charge of its operations

- If no-one in those categories is in the United Kingdom, any other person present in the United Kingdom who has ultimate responsibility for the circus operations

40. Where it is an organisation that has committed the offence under section 1, section 4 of the Act sets out which individuals may be held criminally liable when circuses are considered to be various types of organisations: a company, limited liability partnership, other partnership or any other body or association. For that to happen, those persons (referred to in section 4 as "responsible individuals") must have consented to, or connived in, the organisation's commission of the offence, or the offence must have been attributable to the responsible person's neglect.

- Grant Campbell

There is a problem

Thanks for your feedback

Your feedback helps us to improve this website. Do not give any personal information because we cannot reply to you directly.

- Dictionaries home

- American English

- Collocations

- German-English

- Grammar home

- Practical English Usage

- Learn & Practise Grammar (Beta)

- Word Lists home

- My Word Lists

- Recent additions

- Resources home

- Text Checker

Definition of travelling adjective from the Oxford Advanced Learner's Dictionary

- a travelling circus/exhibition/performer

- The travelling public have had enough of fare increases.

Take your English to the next level

The Oxford Learner’s Thesaurus explains the difference between groups of similar words. Try it for free as part of the Oxford Advanced Learner’s Dictionary app

- Cambridge Dictionary +Plus

Meaning of travelling in English

Your browser doesn't support HTML5 audio

- around Robin Hood's barn idiom

- communication

- super-commuting

- transoceanic

- well travelled

- break-journey

- circumnavigation

You can also find related words, phrases, and synonyms in the topics:

travelling | Business English

Translations of travelling.

Get a quick, free translation!

Word of the Day

doggie day care

a place where owners can leave their dogs when they are at work or away from home in the daytime, or the care the dogs receive when they are there

Dead ringers and peas in pods (Talking about similarities, Part 2)

Learn more with +Plus

- Recent and Recommended {{#preferredDictionaries}} {{name}} {{/preferredDictionaries}}

- Definitions Clear explanations of natural written and spoken English English Learner’s Dictionary Essential British English Essential American English

- Grammar and thesaurus Usage explanations of natural written and spoken English Grammar Thesaurus

- Pronunciation British and American pronunciations with audio English Pronunciation

- English–Chinese (Simplified) Chinese (Simplified)–English

- English–Chinese (Traditional) Chinese (Traditional)–English

- English–Dutch Dutch–English

- English–French French–English

- English–German German–English

- English–Indonesian Indonesian–English

- English–Italian Italian–English

- English–Japanese Japanese–English

- English–Norwegian Norwegian–English

- English–Polish Polish–English

- English–Portuguese Portuguese–English

- English–Spanish Spanish–English

- English–Swedish Swedish–English

- Dictionary +Plus Word Lists

- English Noun Adjective

- Business Noun Adjective

- Translations

- All translations

Add travelling to one of your lists below, or create a new one.

{{message}}

Something went wrong.

There was a problem sending your report.

Words and phrases

Personal account.

- Access or purchase personal subscriptions

- Get our newsletter

- Save searches

- Set display preferences

Institutional access

Sign in with library card

Sign in with username / password

Recommend to your librarian

Institutional account management

Sign in as administrator on Oxford Academic

travelling | traveling noun

- Hide all quotations

What does the noun travelling mean?

There are two meanings listed in OED's entry for the noun travelling . See ‘Meaning & use’ for definitions, usage, and quotation evidence.

How common is the noun travelling ?

How is the noun travelling pronounced, british english, u.s. english, where does the noun travelling come from.

Earliest known use

Middle English

The earliest known use of the noun travelling is in the Middle English period (1150—1500).

OED's earliest evidence for travelling is from 1489, in the writing of John Barbour, ecclesiastic and verse historian.

It is also recorded as an adjective from the Middle English period (1150—1500).

travelling is formed within English, by derivation.

Etymons: travel v. , ‑ing suffix 1 .

Nearby entries

- traveller | traveler, n. a1387–

- travelleress | traveleress, n. 1820–

- traveller-like | traveler-like, adj. 1825–

- traveller's cheque | traveler's cheque, n. 1891–

- traveller's diarrhoea | traveler's diarrhoea, n. 1890–

- travellership | travelership, n. 1824–

- traveller's joy | traveler's joy, n. 1597–

- traveller's palm | traveler's palm, n. 1850–

- traveller's tale | traveler's tale, n. 1747–

- traveller's tree | traveler's tree, n. 1809–

- travelling | traveling, n. 1489–

- travelling | traveling, adj. 1340–

- travelling agent | traveling agent, n. 1737–

- travelling bed | traveling bed, n. 1706–

- travelling cabinet | traveling cabinet, n. 1785–

- travelling carriage | traveling carriage, n. 1667–

- travelling circus | traveling circus, n. 1836–

- travelling couvert, n. 1828–83

- travelling exhibition | traveling exhibition, n. 1800–

- travelling expenses | traveling expenses, n. 1653–

- travelling fellowship | traveling fellowship, n. 1694–

Thank you for visiting Oxford English Dictionary

To continue reading, please sign in below or purchase a subscription. After purchasing, please sign in below to access the content.

Meaning & use