The Messed Up Truth Of Canada's Starlight Tours

First Nations, Inuit, and Métis in Canada have long known that the police cannot be trusted and that Canada has a pretty problematic history overall. But it took until the early 2000s for one of the more horrific police practices targeting Indigenous communities, known as "starlight tours", to be investigated. However, police often didn't leave a paper trail , which left little evidence for convictions even today.

But unfortunately, even when there is evidence that a starlight tour occurred, the most that will often happen is that the police officer will be slapped with a minor charge, serve a handful of months, and perhaps get fired. Meanwhile, those who survive starlight tours are haunted by the memory of their experience and suffer life-long physical and mental consequences .

Although police abuses in Canada are sometimes referred to as starlight tours when they involve being driven in a police cruiser, the starlight tours of Saskatoon, Saskatchewan present a horror all their own. Tragically, there's no way of knowing exactly how many people have been victims of starlight tours in Saskatoon or elsewhere. Those who survive often don't speak out because, according to a CBC report, "it's police investigating police." This is the messed up truth of Canada's starlight tours.

A brief history of First Nations people in Canada

Although the Indigenous population of Canada numbered in the hundreds of thousands before European colonization, those numbers had fallen to about 125,000 recorded individuals by 1867 . Canada's Indigenous people have fought against diseases like smallpox , scourges as rampant as warfare , and assimilation measures like those also forced upon Indigenous people in the United States.

According to Origins , Canada identifies three broad groups of Indigenous peoples as First Nations, Inuit, and Métis, who are legally differentiated depending on their ancestry. And while Canada chose assimilation and segregation compared to the United State's policy of extermination, the National Collaborating Centre for Indigenous Health reports that Indigenous people continue to be oppressed by systemic racism. Under the 1876 Indian Act, according to The Canadian Encyclopedia , many First Nations people were confined to reservations like their Indigenous neighbors in America. The Canadian government implemented a "myriad of regulations, controls, and limits on Indigenous peoples designed to crush their way of life", Origins reports.

In 1886, the Indian Act was amended to make "Indian Residential Schools” mandatory for Indigenous children. Thousands of children were isolated from their communities and traditions in unhealthy and dangerous schools. According to the Independent , over 3,000 children are recorded to have died as a result of the horrifying abuse they experienced at these schools, and at least a dozen died in an attempted escape. The last federally run school wasn't closed until 1996.

What are starlight tours?

In the 2000s, another horrifying practice was brought to the non-Indigenous Canadian public's awareness. Known as "starlight tours," "starlight cruises," or "midnight rides," this appalling practice involve a police officer driving an Indigenous person to city outskirts and leaving them there to, as the Human Rights Watch reports, "walk home in the dead of winter, risking death by hypothermia."

Although the most well-known incidents occurred in 1990, starlight tours have been recorded as early as 1976. Maclean's reports that many incidents happened in Saskatoon, Saskatchewan. According to The Conversation , the practice is especially lethal "when the temperature is -28°C [-18.5°F] and if the long walk back to town is undertaken without proper clothing and shoes."

Racialization, Crime, and Criminal Justice in Canada reports that, although Indigenous organizations and activists repeatedly demanded a public inquiry, the Saskatoon Police Service insisted that starlight tours were "a myth." Meanwhile, per CBC News , some believe that starlight tours weren't inherently sinister and instead "grew out of police frustration at dealing with repeat offenders." Since the police were said to target "drunk or rowdy" individuals, the practice could have been intended to avoid booking people and instead give them a chance to walk off their intoxication. However, other than the fact that this is a terrible way to help someone sober up, this practice is nothing more than a blatant abuse of power by the police force.

The first documented case of a starlight tour

The first recorded case of a starlight tour occurred on May 22nd, 1976, according to Starlight Tour: The Last, Lonely Night of Neil Stonechild . During the night, three First Nations people, an eight-months pregnant woman and two men, were taken from a party by Constable Ken King, driven to the outskirts of the city, dropped off by the isolated Queen Elizabeth power station near the South Saskatchewan River, and forced to walk back in the deadly freezing temperatures . This area was notorious as a dropoff point for Indigenous people, as houses are far enough away that anyone left there by police wouldn't be heard. All three Indigenous people survived this nightmarish experience.

According to Starlight Tour , King reportedly drove them outside the city limits as a punishment for "having liquor in a place other than a dwelling" but neglected to charge them as such. Constable King ended charged with discreditable conduct and neglect of duty and, although he denied the charge, was found guilty and fined $200 on October 15th. However, this fine only amounted to a week's pay .

Who was Neil Stonechild?

Neil Stonechild was a Saulteaux-Cree First Nation teenager who was found frozen in a field on the outskirts of Saskatoon in 1990, The Conversation reports. Police claimed that Neil was responsible for his own death, though he had clearly been injured.

According to the Report of the Commission of Inquiry into Matters Relating to the Death of Neil Stonechild , while the pathologist who examined Stonechild's remains determined that his cause of death was hypothermia, the Saskatoon Police Service decided that there was "no evidence of foul play."

The night Stonechild was abducted, five days before his body was found, the CBC reports that Stonechild was seen by his friend Jason Roy handcuffed in the back of a police car "with his face cut open, bleeding." According to the Canadian Journal of Women and the Law, upon viewing Stonechild's body before burial, his family noted that it looked like his nose had been broken and the marks on his wrists "looked like handcuff marks."

Although these injuries corroborated Roy's account and he twice submitted reports to the police, no one faced any real consequences. Instead, police maintained that Stonechild died of exposure while on the way to prison to turn himself in. But Roy maintained that there's no reason the police would have let Stonechild go under normal circumstances.

Despite struggling with alcoholism, Roy remembers how "Neil loved life. He was a giving person who enjoyed just being a young kid."

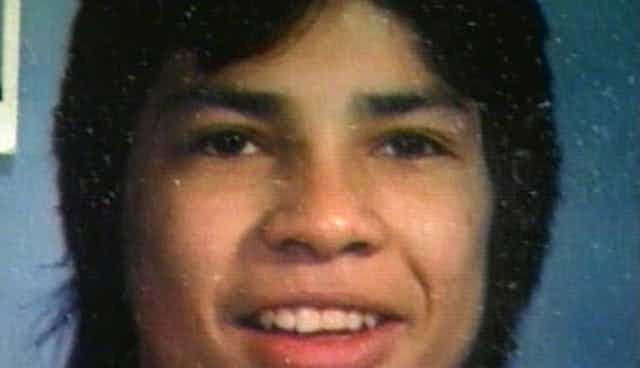

Darrell Night's abduction and starlight tour

On January 28th, 2000, Darrell Night became another victim of the starlight tours, although Maclean's reports that he was thankfully able to survive the three-mile walk home in -7°F weather. Driven outside the city limits of Saskatoon by Officers Ken Munson and Dan Hatchen, Night walked back with just a T-shirt and a jean jacket.

According to VueWeekly , Night says that he was leaving a party when the two officers grabbed and cuffed him. Dumped out into the freezing weather, he called out to the cops driving away, terrified. Their only response was "That's your f—ing problem." Later, when Munson and Hatchen were asked to explain their actions, they claimed that Night had "wanted to be dropped there to 'walk off his anger'."

Finding his way to a power station, Night caught the attention of a security guard and called a taxi. He made it home, becoming one of the reported survivors of a starlight tour. Although Night filed a report, Niche Canada reports that he didn't expect anyone to believe him. But, within days, the frozen bodies of two more First Nations people were discovered in the same area Night was found. As a result, Night was asked for a full report, setting off a chain of events that included reopening the Stonechild case and revealing to the public the extent of this police practice.

More deaths by the power station

On January 29th, 2000 , the day after Darrell Night's abduction, the body of Rodney Naistus was discovered near the Queen Elizabeth power station. Several days later, on February 3rd, Lawrence Wegner's frozen body was also found in the same location. Both of these remains were discovered close to the same spot where Night had also been abandoned by two Saskatoon police officers. The police were finally forced to investigate.

According to the Report of the Commission of Inquiry into Matters Relating to the Death of Neil Stonechild , in response to these deaths and Night's allegations, the Attorney-General for Saskatchewan ordered the Royal Canadian Mounted Police to investigate the freezing deaths.

Although Stonechild's death was not included as part of the initial investigation, after the Saskatoon StarPhoenix published an article by Leslie Perraux that linked Night's story with the 1990 death of Neil Stonechild, the RCMP decided to finally investigate Stonechild's death as well, almost a decade after his death.

Starlight tours led to ineffective inquests

Despite the growing attention, neither Naistus's or Wegner's investigations ended up producing any criminal charges. According to Starlight Tour , "no police involvement was proven in Naistus's death." Instead, it was claimed that Naistus simply wandered away from a house party, possibly while intoxicated, and had frozen to death as a result. The inquests put the onus of responsibility on the victims of the starlight tours, all while insisting that there was no evidence supporting the claims that Canadian police were dropping Indigenous people off in remote, frozen spots. This was despite the fact that Chief Russell Sabo eventually admitted that starlight tours had possibly been occurring for decades.

The inquiry into Darrell Night's incident, however, did result in a conviction, and both Munson and Hatchen were sentenced to eight months in prison. The maximum possible sentence was 10 years. Night eventually left Saskatoon and moved to British Columbia, as he found it incredibly difficult to recover from his traumatic experience while staying in the same environment where it occurred.

Tragically, Night continues to have trouble hearing and communicating as a result of the starlight tour. "I have never received an apology from the police for what was done to me," he told Maclean's .

The inquests for Ironchild and Dustyhorn's starlight tours

Unfortunately, the inquiries into the freezing deaths of Naistus and Wegner mirrored the results of earlier inquests into the deaths of Darcy Dean Ironchild and Lloyd Joseph Dustyhorn in 2000. Both Ironchild and Dustyhorn died shortly after being released from police custody, The Globe and Mail reports.

According to Starlight Tour , Dustyhorn was released from police custody on January 19th, 2000, "despite obvious signs he was hallucinating." He was found dead outside his apartment building only three hours later. Ironchild had also been released from police custody on February 18th, 2000, and was later found dead in his house. Although Ironchild's brother argued that if police had taken Ironchild to a hospital rather than sending him home then he might still be alive, the police were found not to be responsible for Ironchild's death. The same was determined during Dustyhorn's inquest.

Although neither Ironchild's nor Dustyhorn's death technically counts as starlight tours, their deaths and the subsequent inquests were demonstrative of the Saskatoon Police Service's dismissive attitude towards the deaths of Indigenous people.

The inquiry into Stonechild's death

In 2003, 13 years after Stonechild's body was found, an investigation into his death was finally opened. The inquiry lasted a little over a year, and in the end, it was found that Constables Larry Hartwig and Bradley Senger had likely taken Stonechild into custody before his death.

According to the Report of the Commission of Inquiry into Matters Relating to the Death of Neil Stonechild , both Hartwig and Senger argued that they were innocent, but there was evidence suggesting that they were deliberating trying to deceive the inquiry. And according to the Saskatoon StarPhoenix , the original investigation into Stonechild's death was described as "superficial at best and was concluded prematurely."

In November 2004, both Hartwig and Senger were fired from duty. Despite appealing their dismissal, they were rejected. However, no criminal charges were filed and, as of 2021, no officer has ever been convicted for a starlight tour. Even when Hatchen and Munson were jailed, they were merely convicted of "unlawful confinement."

An attempt to rewrite the history of starlight tours

In 2016, an 18-year-old university student named Addison Herman was researching police brutality when he realized that the section about "starlight tours" on the Saskatoon Police Service's Wikipedia page had been deleted. Since IP addresses are recorded whenever someone makes a change in Wikipedia, Herman easily discovered that the change had come from the Saskatoon Police Service itself.

According to Maclean's , it's impossible to know who exactly used the police computer to edit the Wikipedia entry, since upwards of 200 people may have been using the same server at the time. Regardless of who editing the encyclopedia entry, Herman notes that "It was a pretty bold move on their part."

The deletion wasn't a one-time thing. Although as of January 2021, the section on starlight tours appears on the Saskatoon Police Service's Wikipedia page, the section was also deleted (and reincluded) at least twice between 2012 and 2013.

How common are starlight tours?

While starlight tours aren't considered an "official police policy", according to Niche Canada , some people report having survived multiple starlight tours in recent years. According to CBC News , "Greg", who didn't want to share his identity because he was afraid of police retaliation, claims that he's survived four starlight tours.

While police can maintain that Greg has a criminal record, many argue that this is still no excuse for leaving him alone 31 miles outside of Saskatoon. Greg remembers that it took him seven hours to get home from one encounter. When asked why he never made a complaint, Greg stated that "it's police investigating police." Alexus Young, a First Nations filmmaker, is another survivor of starlight tours and violence against transgender women, she told the Aboriginal Multi-Media Society . Young said that officers even took her shoes and coat before leaving her outside Saskatoon.

Despite the fact that many stories like this exist, it's difficult to find physical records of these encounters. As a result, it's difficult to know how many people have died as a result of starlight tours.

These incidents aren't limited to Saskatchewan either. According to CTV News , in Montreal, Julian Menezes reached a $25,000 settlement with the city after accusing Officer Stefanie Trudeau of taking him on a "starlight tour". In the incident with Menezes, Trudeau reportedly drove around erratically in order to "scare and intimidate" him, rather than leaving Menezes to die in the cold.

Police brutality against Indigenous people in Canada continues

Police brutality against non-white people is still rampant in Canada. According to CTV News , compared to a white person in Canada, an Indigenous person is "10 times more likely to have been shot and killed by a police officer in Canada". According to the Yellowhead Institute , a Black person is 20 times more likely to be killed by Canadian police than a white person.

This violence can occur even when the police are called for aid. In June 2020, Chantel Moore , a 26-year old First Nation woman, was killed by police in New Brunswick after they were called to her apartment at 2:30 a.m. for a wellness check.

In addition to suffering physical abuse and death at the hands of the police, Indigenous people in Canada who are the victims of crimes are also ignored by the police to a frightening degree. According to the Human Rights Watch , Canadian law enforcement has failed to address problems leading to the disappearances and deaths of Indigenous girls and women in Canada.

Many describe the thousands lost as a genocide . According to The Guardian , Indigenous women are "targeted for violence more than any other group [and are] 12 times more likely to go missing or be killed." Despite the fact that over decades many have repeatedly called for government inquiries into the high rates of missing and murdered women, the government didn't begin investigating this genocide until 2017.

- International edition

- Australia edition

- Europe edition

Left to freeze by Canada police, Darrell Night exposed their deadly ‘starlight tours’

Cree man, now dead at 56, helped reveal practice in which Saskatoon police drove Indigenous people out of city and abandoned them in sub-zero temperatures

On a freezing winter evening more than 20 years ago, Darrell Night was picked up by police as he left a party in an apartment building in the Canadian city of Saskatoon.

As they drove him to the edge of the city, Night, who was drunk at the time, began to grow fearful. For years, he’d heard stories of so-called “starlight tours” in which the police abandoned Indigenous people in the bitter cold.

“I thought I was dead. All those rumours I heard in the past they were all coming true,” he said in the documentary Two Worlds Colliding . “I told them ‘I’ll freeze to death out here, you guys … The driver said: ‘Thats your f-ing problem’… and then they drove away.”

On that evening in January 2000, the temperature hovered at around -25C (-13F). Night was wearing only a light denim jacket, and didn’t have any gloves or a hat. He managed to survive after finding a nearby power plant and pounding on a door in a desperate attempt to get help.

He credited his survival to chance: he knew the location where he’d been dropped and the only place where he could run to safety. But a few days later two other men – Rodney Naistus and Lawrence Wegner – were found frozen to death in the same area Night had been dropped off.

During a traffic stop, Night decided to tell a veteran police officer about his experience.

That conversation eventually led to an exposé of one of the country’s worst examples of racism in policing, straining the public’s trust in the force and highlighting the deep mistrust Indigenous peoples held against the city’s police.

After Night died earlier this month aged 56, the Cree man has been as hailed as a selfless figure who exposed the brutality of the police force.

University of Alberta professor Tasha Hubbard, who directed the documentary Two Worlds Colliding, said Night’s decision to come forward showed “tremendous courage”.

“He had real empathy for the men who had died,” she told the Guardian. “I think he felt that responsibility to speak up.”

Night died on 2 April and a wake and funeral were recently held at the band hall of the Saulteaux First Nation in Saskatchewan.

The province continues to grapple with the reality of police violence against Indigenous people. Boden Umpherville, 40, was hospitalised in early April after he was Tasered, pepper sprayed and beaten with police batons during an arrest. His family is preparing to take him off life support and the police watchdog is investigating.

Night’s story shocked Saskatoon residents two decades ago but confirmed what many Indigenous people had suspected or experienced. It prompted an investigation by the Royal Canadian Mounted Police, police firings, criminal charges and a public inquest.

The intense public scrutiny also led investigators to revisit the case of Neil Stonechild, a 17-year-old Cree teen who was found dead in a field in the north-west outskirts of Saskatoon in 1990. Temperatures when he was last seen were close to -30 degrees.

At the time, Saskatoon police initially investigated the death and determined that there was no evidence of foul play, but his family claimed the death was never properly investigated.

A public inquest found that police conducted a “superficial and totally inadequate investigation” into the death of Stonechild” and that the teen was last seen bloody and in a police vehicle, but investigators were unable to determine the exact circumstances that led to his death.

Police initially suggested the allegations against officers involved in the “starlight tours” were isolated incidents, but in 2003, Saskatoon police chief Russell Sabo admitted there was a possibility that the force had driven other Indigenous people to the city limits and left them in the cold, including a woman in 1976, according to reporting by the Saskatoon StarPhoenix.

Officers Ken Munson and Dan Hatchen, who abandoned Night that January evening, were later found guilty of unlawful confinement. Both were fired and sentenced to six months in jail.

“[They] have given me a different perspective towards the police,” Night said in his victim impact statement. “I have no trust whatsoever towards policemen.” The province’s court of appeal upheld the Hatchen and Munson convictions in 2003.

In recent years, the police force has been accused of removing references to “starlight tours” on Wikipedia, according to reporting by the StarPhoenix . Police acknowledged to the newspaper that the entry had been “deleted using a computer within the department” but said investigators couldn’t determine who attempted to delete the entry.

Despite multiple public inquiries into the practice, no Saskatoon police officer has been convicted for their role in the freezing deaths of any Indigenous men.

“Darrell Night understood that he wasn’t just speaking for himself when he came forward. There was a sense of responsibility for others,” said Hubbard. “And it’s a real statement to the legacy of courage he’s left us with.”

- Indigenous peoples

Most viewed

Interested in staying up to date with our reports? Subscribe to our newsletter!

Email address:

Subscribe to our newsletter so you can keep up to date with our recent articles

Spheres of Influence

Canada’s Best-Kept Secret: Starlight Tours

Share this:

Listen to this article:

What Are Starlight Tours?

First documented in 1976, Starlight Tours are a Canadian police practice that continues until today. Starlight Tours happen in Western Canada, notably in the provinces of Saskatchewan, Manitoba and Alberta. The practice involves law enforcement officers driving Indigenous people to remote locations and leaving them stranded in sub-zero temperatures. These tours begin with police typically profiling and arresting Indigenous people for alleged drunkenness or disorderly behavior. Such judgements, however, are often founded upon stereotypes and are inaccurate in many instances. Victims will often have their clothes and belongings taken by officers, further exposing them to the harsh elements. Despite intentionally leaving victims defenseless in freezing temperatures, the cause of death for someone who does not survive is simply “hypothermia.” No police officers have been charged with murder for carrying out a Starlight Tour.

Canada’s Legal History With Starlight Tours

For decades, the Canadian public has overlooked Starlight Tours. Within Indigenous communities, this practice is all too familiar. Darrell Night , a Saulteaux First Nation member and survivor of a Starlight Tour, best describes the horrifying nature of these tours. He said of the experience, “I thought I was dead. All those rumours I heard in the past, they were all coming true.”

On January 28, 2000, two officers took Night out of town and left him stranded. He was wearing only a light denim jacket in -25 Celsius weather. Night told the officers, “I’ll freeze to death out here,” to which one officer replied, “That’s your f-ing problem.” Night survived after walking to a nearby power plant and pounding on the door for nearly 30 minutes until a worker heard him. Days after the incident, the frozen bodies of two other Indigenous men – 25-year-old Rodney Naistus and 30-year-old Lawrence Wegner – were found close to where Night was left.

After the two deaths, Night came forward to report his experience to the authorities. The similarity of the three cases prompted an RCMP internal investigation, which led to a series of inquests. Judicial inquiries into the deaths of four men opened. Those men were Lloyd Dustyhorn , Rodney Naistus , Lawrence Wegner and Neil Stonechild . All four were victims of Starlight Tours, and in all four cases, the jury concluded their deaths were accidental, either caused by hypothermia or unknown circumstances.

Night, however, did see some justice . The two police officers who took Night – Ken Munson and Dan Hatchen – were suspended without pay, found guilty of unlawful confinement, and ordered to serve an eight-month jail sentence. Unfortunately, they were free after serving only half of their sentences.

The Province of Saskatchewan created a commission of inquiry into the death of Neil Stonechild, criticizing the Saskatoon Police Service and making eight recommendations for change. They recommended increasing the number of Indigenous police officers, designating an Aboriginal peace officer with the rank of Sergeant, improving race relations and anger management training for officers, and making it easier for the public to file complaints against the police. Nineteen years later, progress remains slow, and Starlight Tours continue happening.

Starlight Tours Today

According to mainstream news networks, the most recent Starlight Tour incident is that of Jeremiah Skunk of Mishkeegogamang First Nation. In the summer of 2019, an Ontario Provincial Police officer took the young man, left him on the side of a highway and told him not to return. He walked, in intense heat, for 10 to 14 hours to Gull Bay, the closest community to him. In a CBC interview, Skunk recalled that he had to drink water out of puddles on the side of the road to stay hydrated, stating, “I could have died.” As shocking as his account is, Skunk is not the most recent Starlight Tour victim, not by a long shot.

On April 4, 2023, a video on the social media platform TikTok described the practice of Starlight Tours. In the comments, hundreds of users united to share their stories. Some shared first-hand accounts, and others shared the stories of their loved ones.

- User A wrote: “Had a cousin and uncle die from this. On their record, it states [they] drank too much. Both never drank in their life.”

- User B wrote: “Happened to my brother! Took his shoes and jacket, he walked back to the city and it took almost 3 hours until he got back.”

- User C said: “Worst is when they take your belt shoelaces [and] warm coats, been stranded outskirts of town myself multiple times … “

- User D wrote: “They did this to me while I was 8 months pregnant in the rain … I only had a tank top and leggings on, it was freezing, probably walked for 6 hours before I got picked up.”

There is a reason why these stories are not brought to the forefront. Without media coverage, the public cannot develop an understanding of an issue, its prevalence, or its impact. Since Starlight Tours are underreported, the public can perceive them as isolated, rare incidents. People can underestimate the severity and scope of this practice and remain unaware that they are a systemic issue.

Additionally, when Starlight Tours go unreported, those responsible escape scrutiny. Media is instrumental in holding individuals and institutions accountable. The Saskatoon Police Service was well aware of this when Addison Herman, a University Student, caught them removing the “Starlight Tours” section from their department’s Wikipedia page multiple times between 2012 and 2013. In 2022 the Saskatchewan Provincial Government chose not to include Starlight Tours in their school curriculum. These actions are not accidental; they are an intentional pattern of erasure and colonial violence.

Police Brutality in Canada

Colonialism is not a past phenomenon. It is an ongoing process of discrimination, trauma, and unfair treatment. Within the criminal justice system, it manifests as systemic racism. Systemic racism is when an institution’s behaviours, policies, or practices create or perpetuate racial inequalities. It helps explain the persistence of Starlight Tours in Canada.

Because Starlight Tours targets Indigenous people, they are a form of racial discrimination and police brutality. Police brutality is excessive force used by a police officer. By forcibly taking Indigenous peoples and abandoning them in extreme conditions, officers abuse their power and cause unnecessary harm. But Tours are not limited to the actions of a few “bad apples” like the media may suggest. The system and structures create and uphold those who perpetrate these acts.

Systemic racism and biases baked into legal institutions are what enable Starlight Tours. Given this, an explicit focus on those systems and structures is pertinent. System-wide change is necessary. Across all levels of government, there needs to be a commitment to addressing structural racism. This commitment means reforming legislation and policy, implementing anti-racism training, funding Indigenous police programs , and re-establishing a genuine relationship with Indigenous communities. The federal government should develop a measure of structural racism to track progress. To ensure transparency, it should make the regularly collected data of the measure public.

What Can You Do?

To help prevent Starlight Tours, a series of steps can be taken. Listen to marginalized voices that too often get silenced. Learn from news networks that amplify Indigenous stories, like APTN News , IndigiNews and Indigenous Network . Sharing information and raising awareness is necessary to help generate public pressure for change. Help out associations that support Indigenous communities like Reconciliation Canada , The Urban Native Youth Association , and The Support Network for Indigenous Women and Women of Colour . If possible, donate to organizations that aid Indigenous people, like Indspire, The Native American Rights Fund , and The Indian Residential School Survivors’ Society.

Madalynn Hausch

Madalynn is currently studying political science at the University of British Columbia. Her research interests include gender in politics, sexual and reproductive health rights, Big Tech, and data justice.... More by Madalynn Hausch

Blessed are the Peacemakers: Explaining the Rise in Sub-Saharan African Intervention and Advocacy

There is an increased interest from Sub-Saharan African countries in acting as peacemakers in matters on and off the continent. Why is this so?

Is Blood Thicker than Water? The Role of the First Lady in Sub-Saharan Africa

Putin’s War in Ukraine Pushes Latvia To Take Drastic Measures Toward Ethnic Russian Residents

The Stolen Generation: The Deportations of Ukrainian Children To Russia

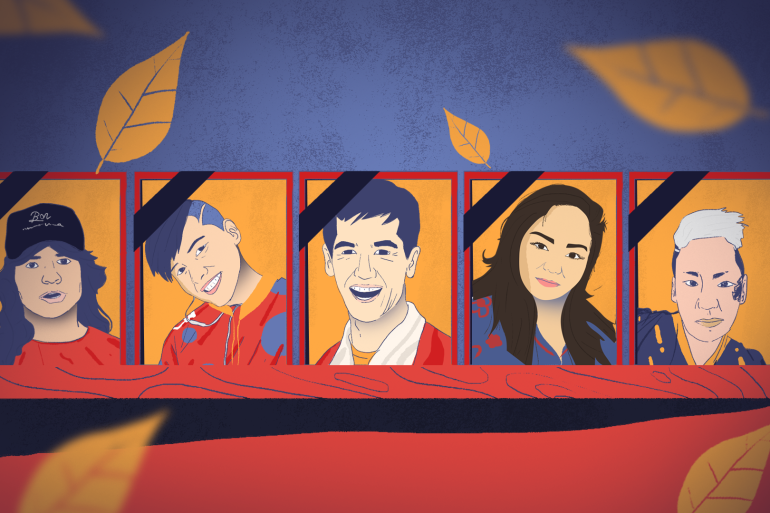

The Indigenous people killed by Canada’s police

The stories of Indigenous people who died in police encounters in Canada and the loved ones they left behind.

Despite making up just five percent of Canada’s population, 30 percent of the country’s prisoners are Indigenous. Across the prairie provinces of Manitoba, Saskatchewan and Alberta – regions that have higher populations of Indigenous people – that number rises to 54 percent.

According to a 2017 CTV News analysis, an Indigenous person in Canada is more than 10 times more likely to be shot and killed by a police officer than a white person. Between 2017 and 2020, 25 Indigenous people were shot and killed by the RCMP, Canada’s federal and national police service.

Keep reading

Is resource extraction killing indigenous women, chief allan adam on being beaten by police and indigenous rights, ‘it was sheer hatred’: the indigenous woman taunted as she died, know their names: black people killed by the police in the us external link this article will be opened in a new browser window.

The latest case came on February 27, when Julian Jones, a 28-year-old Tla-o-qui-aht man, was shot and killed in British Columbia after Tofino police responded to a call for help from the Opitsaht reserve, which is accessible only by boat.

It was the second police killing of a Tla-o-qui-aht First Nation member in less than a year, following the death of Chantel Moore in June 2020.

Here are the stories of some of the Indigenous men and women who have been killed in encounters with Canadian police.

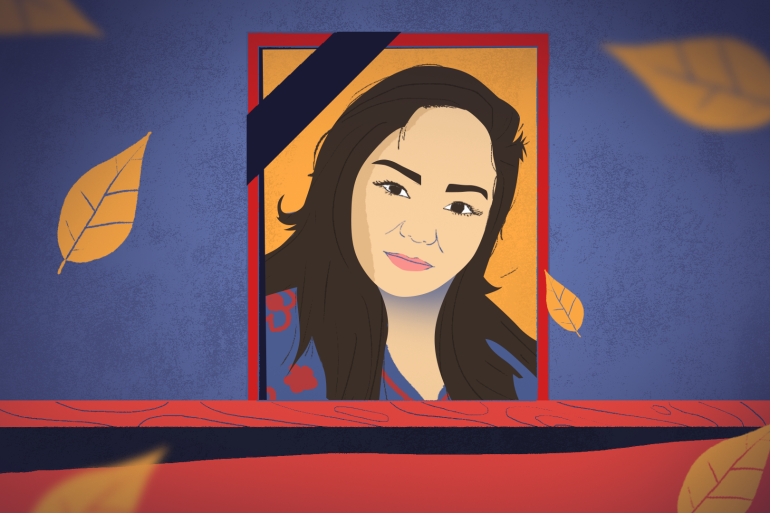

‘I want to get angel wings’ Chantel Moore, 26 – killed June 4, 2020

In the early hours of the morning on June 4, 2020, police in the New Brunswick city of Edmundston reportedly responded to a call from Chantel Moore’s boyfriend requesting a wellness check. Her boyfriend, who lived more than 1,000km (600 miles) away in Toronto, reportedly believed that Chantel was being harassed. The 26-year-old Tla-o-qui-aht First Nation member from British Columbia had recently moved to New Brunswick to be closer to her six-year-old daughter, who lived with Chantel’s mother.

A few minutes later, Chantel – who her family described as “a good mom”, someone who “made friends wherever she went” and “loved to make people laugh” – was dead.

According to the police, Chantel had walked out of her apartment onto a balcony with a knife and had threatened the officer, who then shot her.

“I don’t understand how someone dies during a wellness check,” Indigenous Services Minister Marc Miller said at a news conference following Chantel’s death.

After Chantel’s body was returned to British Columbia, her maternal grandmother, Grace Frank, and her mother, Martha Martin, went to view it.

“Her face was bruised, her right eye sunk in. She had seven gunshot wounds on her body and her left leg wasn’t attached below the kneecap,” Grace recalled tearfully, adding that the police had not offered any explanation for the condition of her body.

The family wanted to protect Chantel’s daughter, Gracie – named after her great-grandmother – from learning how her mother died, but the six-year-old accidentally saw a news report about it on TV. Her great-grandmother says it left her devastated: “Gracie is so sad. She says, ‘I want to get angel wings. I want to go see my mom.’ And then she’s scared and cries, ‘I don’t wanna be shot like that, I don’t wanna die like that.'”

Grace remembered how Chantel would go out of her way to give her daughter the best Christmases and birthdays she could, adding: “Chantel was such a good mommy.”

“[She] was the kindest, [most] caring, loving, supportive, bubbly person. She never had hate for anyone. People loved her.”

When asked about the condition of Chantel’s body, Mychèle Poitras, communications director for the City of Edmundston, said: “No comments can be made since the file is with the Provincial Prosecutor’s Office.”

The name of the officer who shot Chantel has not been released, but eight investigators with Quebec’s independent police watchdog group (New Brunswick does not have its own) have completed an investigation into her death. The Bureau des enquetes independantes forwarded its report to New Brunswick’s Public Prosecution Service and to the case coroner in December. The prosecutions office has said it will review the report and determine whether to charge the officer.

The Tla-o-qui-aht First Nation is demanding that the officer be charged with murder and that body cameras be mandatory for all police officers working with the public. It has also requested a full national inquiry into the root causes of police brutality against Indigenous people.

“This killing was completely senseless,” the Nation said in a press release. “At the Missing and Murdered Indigenous Women and Girls Inquiry, RCMP Commissioner Brenda Lucki committed to do better by First Nations. She said, ‘I’m sorry that for too many of you, the RCMP was not the police service that it needed to be during this terrible time in your life. It is very clear to me that the RCMP could have done better and I promise to you we will do better.’ We are still waiting for ‘better’ and Chantel certainly deserved ‘better.’”

In mid-November, less than six months after Chantel’s death, her 23-year-old brother Mike Martin took his own life while being held in a correctional centre in British Columbia. “I’m trying to be OK but I’m sad,” wrote Grace in a social media post in December. “I’m hurting. I’m angry. I’m full of rage. I’m full of disgust. I think about my granddaughter and my grandson – they should both be alive. It’s so unfair they’re gone … I will not give up until justice is served. My heart is aching.”

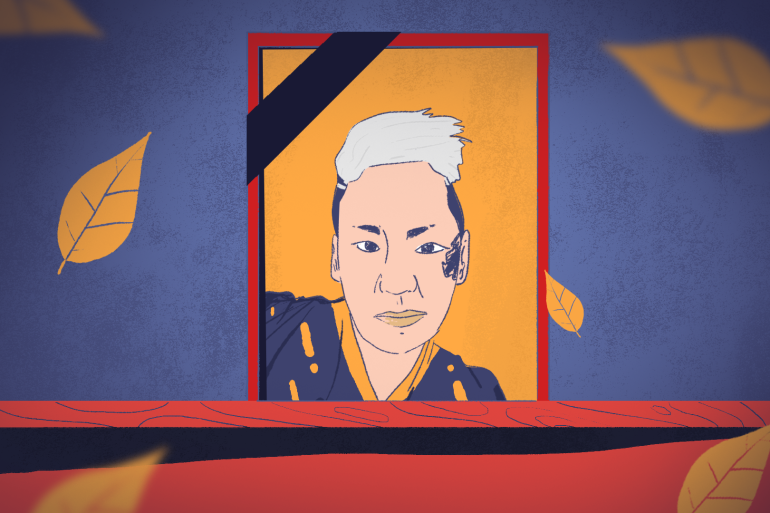

The ‘starlight tours’ Neil Stonechild, 17 – killed November 1990

On the golden, wheat-covered prairies of Saskatchewan, a deadly phenomenon known as the “starlight tours” has been threatening Indigenous people for decades.

No one here is certain where or when the term originated, but Indigenous residents know exactly what it stands for: police taking Indigenous people – often said to have been picked up while intoxicated – and dropping them off at the edge of the city of Saskatoon at night, where temperatures regularly drop to as low as -28C (-20F) during winter.

In November 1990, a 17-year-old Saulteaux First Nations boy was found frozen to death in a field on the outskirts of Saskatoon. Neil Stonechild was face down in the snow, wearing one shoe, and had cut marks on his face and arms. He was found by construction workers on November 29 – five days after he was last seen.

An autopsy indicated that he had died of hypothermia. But his devastated family suspected foul play.

A police investigation into his death was closed after just three days. Former Saskatoon police Sergeant Keith Jarvis, who conducted the investigation, explained in his report: “It is felt that unless something concrete by way of evidence to the contrary is obtained, the deceased died from exposure and froze to death.”

At the time of his death, Neil was living between a group home – accommodation that houses multiple children and young people in the foster care system – in the west end of Saskatoon and his mother’s house.

According to his older brother, Dean Lindgren, who is now 54, Neil was a “good kid” who dabbled in “petty crime” but was not involved in violent crime or gangs.

The night Neil died he was wearing his brother’s high school letterman jacket. It was, Dean remembered, one of his most prized possessions. “For a long time he kept asking me, ‘Bro, can I have your jacket?’” said Dean, who finally relented and gave it to his brother, who wore it “proudly” around Saskatoon.

Neil was an athlete, who excelled at wrestling, Dean recalled.

The two brothers had a strong bond, even though they had only known each other for two-and-a-half years when Neil died. Dean had been taken from his family as part of the “60s scoop”, a practice enacted by provincial and federal Canadian governments from the 1960s to the 1980s in which Indigenous children were taken from their families and adopted by white families across Canada and the US.

After finishing high school, Dean travelled from his adoptive home in Minnesota in the US to find his biological family in Saskatoon. He immediately bonded with his younger brother and said that the week before he died, the two brothers had planned to travel to the province of Ontario to pick up a car Dean had bought and drive it back to Saskatoon together.

“He wanted to come so bad,” Dean said of his brother. But in the end, Dean went alone. “I kick myself every time I talk about this,” he said.

Driving back to Saskatoon, Dean hit black ice and destroyed his new car. He borrowed a stranger’s phone to call home. The US Army veteran breaks down in tears as he describes what happened next.

“I called my cousin Andrea. I was frantic about my car. But she asked me, ‘Are you sitting down?… Dean, your brother was killed.’”

His world momentarily stopped. Then the words hit him – hard. He took a bus back to Saskatoon.

Dean remembers hearing that Neil was with his 16-year-old friend Jason Roy the night he went missing. But, for 10 years, Jason did not talk about what happened that night. He later explained in a phone call from his home in Saskatoon that he had been traumatised and scared of potential repercussions for speaking out.

Then, on January 19, 2000, Lloyd Dustyhorn, a 53-year-old First Nations man was found frozen to death in Saskatoon. The day before he had been taken into custody by police for public intoxication – in May 2001, following an inquest, a jury decided that his death had been caused by hypothermia.

Later that month, Darryl Night, a Cree man from Saskatoon, told police that two officers had dropped him off several miles outside of Saskatoon in freezing temperatures. Darryl had been having a drunken argument with his uncle and said the officers picked him up outside his uncle’s apartment before dawn on January 28. He was wearing only a T-shirt and running shoes when they left him in a remote rural area outside the city. He managed to walk several miles to a power station where a watchman let him call a taxi.

The next day, the shirtless body of Rodney Naistus, a 25-year-old Indigenous man, was found near where Darryl said the police officers had dropped him off. A few days later, on February 3, 2000, the body of another Indigenous man, 30-year-old Lawrence Kim Wegner, who had last been seen three days earlier, was found wearing only a T-shirt, socks and jeans. Both men appeared to have frozen to death, possibly dying within hours of being released from police custody, according to police investigations and public inquests.

These cases prompted the Province of Saskatchewan to hold an inquiry into the alleged “starlight tours” and to re-examine Neil’s death.

Jason testified at the inquiry, telling it about the last time he had seen his friend alive on that bitterly cold November night in 1990. He and Neil had been walking in the city’s west end after drinking at an apartment building in the area, he said. The two briefly separated, Jason recalled, and the next time he saw Neil he was in the backseat of a police cruiser, with a bloodied face, screaming for help and telling Jason: “They’re going to kill me.”

The inquiry found that Neil was in the custody of police Constables Larry Hartwig and Bradley Senger and that the injuries and marks to his body “were likely caused by handcuffs.” The officers denied having been in contact with Neil the night he died, but the evidence contradicted their claim and the two were dismissed from duty in November 2004. A court upheld the findings of the inquiry when the two officers appealed against it.

Despite this, no Saskatoon police officer has been tried for Neil’s death or those of any of the other Indigenous people who froze to death.

Today, Dean says he harbours hatred for the officers he believes took the life of his brother. “I will never forgive Hartwig and Senger, never,” he said, angrily.

When George Floyd was killed by US police in Minneapolis, Dean said it stirred up memories. “I understand exactly what the family (George Floyd’s) is going through,” he said. “When I saw the cops killing George Floyd on the video, I had instant rage. Down here it’s not safe for the Blacks and up in Canada it’s bad for the Natives.”

Back in Saskatoon, Jason is working to overcome the trauma of the last time he saw his friend. He wants the police to implement the recommendations of the inquiry into his friend’s death, which included cultural and sensitivity training to equip police to deal with high-stress situations involving Indigenous people who are often dealing with trauma as a result of generations of abuse, neglect and discrimination.

“The police have only found different ways to abuse our people. My people are still being abused,” he said. “But I’m not scared of them – there is no way I was going to let them win.”

‘His life was only worth 20 minutes of their time’ Rodney Levi, 48 – killed June 12, 2020

Eight days after the death of Chantel Moore, 48-year-old Rodney Levi, a Metepenagiag Mi’kmaq man, was killed in the same province.

Late in the afternoon of June 12, the Sunny Corner RCMP Detachment reportedly received a call about a man acting strangely at a home near the Metepenagiag First Nation.

According to a report by the Bureau des enquêtes indépendantes du Québec when police arrived at the scene, Rodney was armed with knives and charged at one of the two officers. A taser was deployed three times but failed to subdue him. One of the officers shot Rodney twice in the chest. He was pronounced dead at the hospital.

Investigators from the Bureau interviewed witnesses, one of whom described Rodney as “being severely depressed” in the days before his death and as having talked about “suicide by RCMP”.

Rodney’s brother-in-law, Norman Ward, told Al Jazeera the father-of three had battled “demons” in the form of drug addiction but added that he did not believe he posed a threat to anyone.

“With Rodney gone, a big piece is missing as he always brought everyone together,” he said. “Things will never be the same with him gone. He didn’t die of natural causes. His life was stolen, not just from him but from everyone who loved him.”

Norman described him as having a way with people, especially children. “All his nieces and nephews looked up to him. He went out of his way to play with them. He was like a big kid.”

According to Lisa Levi, Rodney’s sister, he had been attending a BBQ at the home of his pastor from the Boom Road Pentecostal Church – a church he had been attending on and off for approximately three years – when he was shot by police on the back deck.

“From what I understand, Rodney was invited by Pastor Brodie [MacLeod] to have supper with the family. They all knew Rodney and loved him. Some time during the time he was there Rodney became paranoid and had put a knife in his hoodie pocket for protection. Someone (we’re not sure who) called the police,” Lisa explained.

Pastor Brodie MacLeod released a statement after Rodney’s death to dispel the rumours that he had been an “unwanted guest”. “Rodney Levi was a welcomed guest at our home and he attended our residence when he shared a meal with my family and I on Friday evening,” he wrote.

Lisa said Rodney had been trying for several months to get psychiatric help but had been denied admission for treatment at the local hospital.

The police spoke to Rodney for 20 minutes before he was shot. “That officer showed up, knew Rodney was Indigenous and decided that Rodney was not worth the effort to talk to. Because the very next week, a white guy at the Miramichi hospital held a nurse at knifepoint. They gave that man a hostage negotiator and hours to talk him down. Our Rodney was given 20 minutes! That’s the hardest part – knowing Rodney’s life was only worth 20 minutes of their time,” said Lisa.

“I wonder, did he suffer and was he scared?” she said, crying.

Lisa says she now experiences anxiety when driving outside of her community. “A week after Rodney was killed, I was driving down the highway and a cop pulled out behind me. I was sweating, started to get anxious. Even though my vehicle was insured and registered, I didn’t feel safe because I’m Indigenous.”

Her children, aged 7, 13 and 14, are also afraid, she adds. “They know how their uncle was. He was so nice, so gentle. Never violent. It makes me cry. I want to protect my kids to not have to go through this, but racism is still here.”

Norman is convinced Rodney would still be alive if he were white. “The whole justice system is against us,” he said. “There’s so much racism in this area. They (police) beat up our people. All they want to do is arrest us and be aggressive to us. There is still so much tension here since Rodney died.”

The RCMP is not currently commenting on Rodney’s death as the case is being reviewed by the New Brunswick Prosecution Service.

‘She was a kid’ Eishia Hudson, 16 – killed April 8, 2020

On April 8, 2020, police in Winnipeg, Manitoba, shot and killed Eishia Hudson, a 16-year-old First Nations girl. Police say they received a report that a group of teenagers had robbed a liquor store in the Sage Creek area. Within minutes, several police vehicles were chasing the stolen SUV the teenagers were in.

The pursuit came to an end when the police cars blocked in the SUV and an officer shot Eishia, who had been driving the stolen SUV. She was transported to hospital but succumbed to her injuries.

The night Eishia was killed, her father, William Hudson, got a call from one of his other daughters expressing concern about Eishia. He went out looking for her.

“I went around to every hospital and called all the police stations,” he said. “No one told me anything.”

A little later, he heard the news from one of his other daughters.

“It’s tough. It’s unbelievable. It’s still hard for me to believe,” he said.

Just 12 hours later, one of his closest friends, 36-year-old Indigenous father-of-three Jason Collins, had been shot and killed by Winnipeg police officers responding to a domestic violence call.

Of his daughter, William said, “[she had a smile] so bright it didn’t matter how you were feeling or what you were going through, she brought brightness to anyone she was around. She had a positive attitude towards everything”.

He says Eishia was not a troublemaker and describes her as a happy person who loved to play sports and make people laugh.

“I enjoyed laughing with her, listening to her sing, watching her play sports. Every moment I had with Eishia is my favourite memory of her.”

He believes racism played a role in her death.

“It’s hard to be Indigenous in Canada. Where I grew up here in the north end, it’s lower-income, there’s gangs. We grew up with racist cops and a racist child welfare system,” William explained.

The family held a funeral for Eishia in April amid COVID-19 lockdowns. William says hundreds of people turned up at the funeral home to pay their respects before she was cremated but only 10 could be ushered through at a time.

The family says it is waiting to get answers from the police about why other tactics were not used to apprehend her before burying her remains.

William says Winnipeg’s Indigenous community has been a great source of support for him. He has organised multiple rallies and vigils for Eishia, which he says helps to make him feel as though he is not carrying the load of her loss alone. But, he says, neither the police nor the city or provincial authorities have reached out to him.

His younger children are afraid to leave the house since Eishia died, he explained, adding that whenever he takes his five-year-old daughter to the local grocery store, she grabs his leg if she sees a police officer on patrol.

“For us, when we leave the house, we know we’re leaving as an Indigenous person. To be on guard. I hope one day it will change.”

Following an investigation into Eisha’s death, Manitoba’s Independent Investigation Unit (IIU) concluded that there was no evidence the officer had been unjustified in using lethal force. William dismissed the report as “biased”.

“My daughter, her life mattered. She was a kid and what the cops did, that was wrong,” William said, adding: “It has to come to an end.”

‘My sunshine girl’ Josephine Pelletier, 33 – killed May 17, 2018

Josephine Pelletier was shot dead by police in Calgary, Alberta, on May 17, 2018. The 33-year-old Cree woman was with her 18 year-old-son Elijah, and according to police, was barricaded in the basement of a residence that was not her home.

“I had a strange feeling about Josephine and her boy [around the time she was killed],” Josephine’s mother, Donna Pelletier, explained during a phone call from her home in Saskatchewan.

Family friends called to tell her the news after learning of Josephine’s death on social media.

“I said, ‘If this is about Josephine, I don’t want to hear it.’ Everything went blank after that,” she recalled.

Josephine had attended one of Canada’s last residential schools – which closed in 1996. In an interview before her death, she had described to this writer the relentless verbal, physical and sexual abuse she had endured there.

Canada’s federal residential school system, which started in 1883, forcibly removed Indigenous children from their families, communities and cultures.

After leaving school, Josephine spent much of her life in jail. But, in 2015, she had reached out to the Aboriginal Peoples Television Network (APTN) from a half-way house in Calgary to share her story and plead for help. “I need help,” she told the channel. “How to learn to unlock my mind from being an angry person. From being locked up all the time and fighting. I want to be in control of my mind, feelings, my heart and my body. I want to be a mom. I want to give my son something to look at and be proud of.”

Josephine had been on the run from a Calgary half-way house for a couple of days when the upstairs occupants of the residence where she was killed called the police to report a home invasion. Police arrived with a K9 unit and a tactical team. According to news reports, police officers heard sounds of distress from inside and two officers fired live rounds at Josephine, who was unarmed. She died on the scene.

Police also shot Elijah with rubber bullets, rendering him unconscious. To this day, Donna says, he has no recollection of his mother’s death.

About a week and a half after Josephine was killed, Donna had raised enough money through an online appeal to be able to bring her daughter’s body home to Saskatchewan.

“They didn’t wipe her up. There was still blood on her body. There was a bullet by her ear, one on the back of her head, one on her arm – she must have put her arms up. I saw three bullets, but then I couldn’t look any more,” she explained.

Josephine was buried in the Muskowekwan First Nation that June. Elijah could not attend the funeral because he was in jail facing various charges related to the incident on the day of his mother’s death. A court subsequently ordered that he be admitted to a psychiatric hospital, where he remains today.

“They found him hanging at the Edmonton Remand Center,” said Donna of her now 20-year-old grandson. “It was the third time he tried to commit suicide.”

She described Elijah as smart, quiet, but quick-tempered, like his mother. “But now, they keep him drugged up, he doesn’t sound like himself.”

Donna says she has been left with unanswered questions. “They (police) won’t give me answers. They keep giving me the run-around.”

When she visits Josephine’s grave, the pain is still fresh. Although her daughter lived a troubled life, Donna says she now likes to imagine that her “sunshine girl” is at peace with the angels.

Josephine’s death is currently under investigation by the Alberta Serious Incident Response Team (ASIRT). The ASIRT told Al Jazeera by email that it is unsure when a decision will be made regarding the actions of police in Josephine’s death.

Sask. man at centre of historic 'Starlight Tours' police misconduct case has died

Darrell night spoke out after he was left by police to freeze outside saskatoon in january 2000.

Social Sharing

A man who spoke out more than 20 years ago after being taken on a "Starlight Tour" by Saskatoon police has died.

In January of 2000, Darrell Night was driven out of the city by two Saskatoon police officers and abandoned without winter clothing. He survived after a power plant worker heard him knocking on the door.

The frozen bodies of two other Indigenous men — Rodney Naistus and Lawrence Wegner — were found around this time in the same area.

Night agreed to tell his story publicly and to an officer who agreed to pursue the case. It ignited a wave of firings, criminal charges and protests against a police practice known as Starlight Tours.

"He felt a deep empathy for the men who died. He felt that it was his responsibility to come forward," said University of Alberta professor Tasha Hubbard, who featured Night in her film, Two Worlds Colliding .

"I think people should understand just how much courage that took for him to do that."

Hubbard said it was only two decades ago, but attitudes were far different. Canadians were only beginning to listen to the stories of residential school survivors. Idle No More, Black Lives Matter and other movements didn't exist. No one had cell phone recordings or posts on social media.

- How the Idle No More movement helped lay the foundation for reconciliation in Canada

- Black Prairies Black on the Prairies: What it means to be Black in Alberta, Saskatchewan and Manitoba

Two officers were convicted in Night's case. Investigations into the deaths of Naistus and Wegner were inconclusive.

"He was essentially kidnapped, taken away and dropped off in the middle of an extremely cold winter night on the outskirts of Saskatoon. And having survived that trauma, he had nonetheless the wherewithal to to come forward with his story. He displayed some exceptional courage," said Night's former lawyer, Donald Worme.

Night died earlier this month at age 56. A wake and funeral were held at the Saulteaux First Nation located approximately 150 kilometres northwest of Saskatoon. The cause of death is not known.

Worme said the overt racism within the police force and the rest of society has diminished, but there's still a lot of work to do combating institutional racism and other forms of injustice.

"I think there's no question that Darrell Night made a difference in the city of Saskatoon. His name is synonymous with pushback against police misconduct in this city," Worme said.

"His passing is a sad day for, you know, not just for his family, but I think for those who who believe in the kind of justice that he advocated."

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Jason Warick is a reporter with CBC Saskatoon.

Related Stories

- Quebec successfully pushes back against rise in measles cases

- No charges for Winnipeg officers after man died in custody last summer: police watchdog

- Coroner's inquest hears Sask. man died in custody from self-inflicted gunshot wound

- Man who died on Hamilton mall rooftop in 2020 had 'very difficult' life, inquest hears

- Their dad died but Toronto police didn't tell them. They want to make sure it doesn't happen to anyone else

Remembering Neil Stonechild and exposing systemic racism in policing

Associate Professor of Gender, Religion and Critical Studies; Academic Director of the Community Research Unit, University of Regina

Disclosure statement

Michelle Stewart has received funding from a wide-range of agencies including but not limited to: Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council, Canadian Institutes of Health Research, National Science Foundation, and Saskatchewan Health Research Foundation.

University of Regina provides funding as a member of The Conversation CA-FR.

University of Regina provides funding as a member of The Conversation CA.

View all partners

On Nov. 29, 1990, the body of Neil Stonechild, a Saulteaux First Nations teen, was found frozen in a field on the outskirts of Saskatoon. It was -28C. He was just 17-years-old at the time of his death. He was found wearing only jeans and a light jacket and was missing one shoe.

Light jacket.

On Dec. 5, 1990, the Saskatoon Police Service closed the investigation into the death of Neil Stonechild. Despite visible injuries to the body of the Indigenous teenager, the file was closed. The investigation closed prior to receiving the Coroner’s Report, prior to receiving the toxicology report and prior to completing interviews with all witnesses.

In her book, Dying from Improvement , critical race scholar Sherene Razack discusses the Stonechild inquiry. She reports that the investigating officer said: “the kid went out, got drunk, went for a walk and froze to death.”

It would take over a decade and the freezing deaths of two more men and the near-death of another to crack the case wide open. Neil, the teenager, once dismissed as drunk and responsible for his own death, would become subject of a public inquiry that would lead to the firing of two police officers. His death would become synonymous with a racialized police practice called starlight tours.

Starlight tours describes a practice of police taking Indigenous people (said to have been picked up drunk or rowdy) and dropping them off at the edge of the city in the middle of the winter night . As Razak writes: “That there is a popular term [for this practice] is testimony to the fact that it happened more than once. The practice of drop-offs is a lethal one when the temperature is -28C and if the long walk back to town is undertaken without proper clothing and shoes.”

Remembering Neil

It’s November 2019, and I am talking to Neil’s brother, Chris Lindgren Astakeesic, about his brother’s death nearly 30 years ago. Chris recalls when his sister told him that Neil had died.

He was devastated. He had only been reunited with his younger brother and family in recent years after being in the foster care system and living outside Saskatchewan. Coming back into his family’s life, Chris made an immediate connection with Neil. Despite not being raised together, they shared a love of wrestling and created a solid bond.

Chris remembers Neil as many others did as a “fun-loving and very caring” person, adding that he “loved messing with him. He was a great kid and great brother. He loved life.”

Neil was wearing the letterman jacket that Chris gave him when he was found in the field. Stella, Neil’s mom, talked about the jacket during the inquiry into his death. The jacket had particular importance to Chris. Neil had treasured it and so Chris gave Neil the jacket before leaving for a trip to Ontario.

Given the sentimental importance of the jacket, Chris went to the police after the investigation concluded to request Neil’s belongings including the jacket. The Saskatoon Police told him they couldn’t find it. “I don’t even know if this has been told publicly,” says Chris. “But we couldn’t find any of his stuff.” The jacket and Neil’s other possessions were never returned. Chris tells me his mom, Stella, “was heartbroken.”

The inquiry

Chris speaks with a broken voice, recalling with vivid detail the time around Neil’s death and his experiences attending the inquiry as he drove back and forth to Saskatoon to attend as many dates as possible and be with his family.

I ask Chris what he thinks happened to Neil that night.

Chris mentions two police constables. “I think Hartwig and Senger had some fun, tried to scare him and it went to far,” he says. Chris recalls that Neil’s friend, Jason Roy, reported seeing Neil in the back of a police car that night. When Jason last saw Neil he was begging for help, screaming, “Help me, they are going to kill me.”

The findings of the inquiry established that police constables Larry Hartwig and Bradley Senger “took Stonechild into custody” and that the injuries and marks to his body “were likely caused by handcuffs.”

Hartwig and Senger argued their innocence and said they did not have contact with Stonechild that night. Evidence to the contrary was presented.

The evidence led Justice David H. Wright to conclude that Hartwig did recall the events that night (despite his assertions otherwise) and as such “ his assertions are deliberate deception designed to conceal his involvement .” The inquiry, through witness after witness’ testimony, offered a lesson in systemic racism in a settler state. But the recommendations did not address systemic racism and instead focused primarily on race relations.

Hartwig and Senger were dismissed from duty in November 2004 within a month of the report’s release. They appealed. Their appeals were rejected and the courts upheld the findings of the inquiry.

Stereotypes of victims hinder justice

The question of Neil’s personal belongings mirrors more recent stories in Saskatchewan. There are too many stories of other families that did not receive personal items from their loved ones. Often this is connected to a lack of investigation into sudden deaths.

After Nadine Machiskinic , a 29-year-old Indigenous mother of four died in Regina, the family reported her items were thrown away before a police investigation was even able to begin .

After 14-year-old Haven Dubois drowned in a shallow ravine, his family challenged the coroner’s report that had ruled his death an accident with marijuana as a contributing factor. His death had limited investigation.

The families of Haven and Nadine both argue their loved ones did not get a full investigation because of perceptions about them, as Indigenous people, on the prairies.

Like Neil’s family, these families fight for justice for years on end. They fight back against the ruling of accidental death. They call for inquiries and inquests. They fight back against assumptions made about the intoxication of the victim versus the real possibility of foul play.

Fifteen years later after the inquiry

The image of Neil Stonechild’s body lying in a frozen field still haunts the prairies.

The starlight tours continue to have ripple effects and impact relations between Indigenous peoples and police. The release of the 2004 Report of the Commission of Inquiry Into Matters Relating to the Death of Neil Stonechild called for reforms including more police accountability.

Of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission’s 94 Calls to Action, 18 deal with the criminal justice system . No. 39 calls upon the federal government to develop a national plan to collect and publish data on the criminal victimization of Aboriginal people, and No. 38 calls upon all levels of government to commit to eliminating the over-representation of Aboriginal youth in custody over the next decade. The TRC also placed emphasis on truth. We need to tell the truth about police practices and starlight tours in the prairies in Canada.

Concerns have been raised by the Federation of Sovereign Indigenous Nations (FSIN). “We have come a long way in 15 years but there is always room for improvement,” Dutch Lerat, the Vice Chief for the Federation of Sovereign Indigenous Nations, told APTN. “ We urge the Ministry of Justice to improve upon the public complaints process with emphasis on creating a civilian-led oversight authority .”

Saskatchewan is one of the last provinces to adopt independent civilian oversight despite ongoing, high-profile cases that raise concerns about how police work .

I spoke to Chris on the phone between anniversaries that no family should have to know: the freezing death of your loved one and the release of the findings of a public inquiry into their death.

“I am hoping [other families] can go back to this story for future reference and for future kids, so this doesn’t happen again.”

In honour of his memory: Neil Stonechild was a 17-year-old boy. His family loved him. Neil froze to death and some of the last people to see him alive were two police officers. Neil Stonechild died as a result of the starlight tours.

[ Deep knowledge, daily. Sign up for The Conversation’s newsletter .]

- Critical race

- Focus: Truth and Reconciliation in Canada

Lecturer / Senior Lecturer - Marketing

Communications and Engagement Officer, Corporate Finance Property and Sustainability

Assistant Editor - 1 year cadetship

Executive Dean, Faculty of Health

Lecturer/Senior Lecturer, Earth System Science (School of Science)

IMAGES