Internet Explorer Alert

It appears you are using Internet Explorer as your web browser. Please note, Internet Explorer is no longer up-to-date and can cause problems in how this website functions This site functions best using the latest versions of any of the following browsers: Edge, Firefox, Chrome, Opera, or Safari . You can find the latest versions of these browsers at https://browsehappy.com

- Publications

- HealthyChildren.org

Shopping cart

Order Subtotal

Your cart is empty.

Looks like you haven't added anything to your cart.

- Career Resources

- Philanthropy

- About the AAP

- Confidentiality in the Care of Adolescents: Policy Statement

- Confidentiality in the Care of Adolescents: Technical Report

- AAP Policy Offers Recommendations to Safeguard Teens’ Health Information

- One-on-One Time with the Pediatrician

- American Academy of Pediatrics Releases Guidance on Maintaining Confidentiality in Care of Adolescents

- News Releases

- Policy Collections

- The State of Children in 2020

- Healthy Children

- Secure Families

- Strong Communities

- A Leading Nation for Youth

- Transition Plan: Advancing Child Health in the Biden-Harris Administration

- Health Care Access & Coverage

- Immigrant Child Health

- Gun Violence Prevention

- Tobacco & E-Cigarettes

- Child Nutrition

- Assault Weapons Bans

- Childhood Immunizations

- E-Cigarette and Tobacco Products

- Children’s Health Care Coverage Fact Sheets

- Opioid Fact Sheets

- Advocacy Training Modules

- Subspecialty Advocacy Report

- AAP Washington Office Internship

- Online Courses

- Live and Virtual Activities

- National Conference and Exhibition

- Prep®- Pediatric Review and Education Programs

- Journals and Publications

- NRP LMS Login

- Patient Care

- Practice Management

- AAP Committees

- AAP Councils

- AAP Sections

- Volunteer Network

- Join a Chapter

- Chapter Websites

- Chapter Executive Directors

- District Map

- Create Account

- Materials & Tools

- Clinical Practice

- States & Communities

- Quality Improvement

- Implementation Stories

Well-Child Visits: Parent and Patient Education

The Bright Futures Parent and Patient Educational Handouts help guide anticipatory guidance and reinforce key messages (organized around the 5 priorities in each visit) for the family. Each educational handout is written in plain language to ensure the information is clear, concise, relevant, and easy to understand. Each educational handout is available in English and Spanish (in HTML and PDF format). Beginning at the 7 year visit , there is both a Parent and Patient education handout (in English and Spanish).

For the Bright Futures Parent Handouts for well-child visits up to 2 years of age , translations of 12 additional languages (PDF format) are made possible thanks to the generous support of members, staff, and businesses who donate to the AAP Friends of Children Fund . The 12 additional languages are Arabic, Bengali, Chinese, French, Haitian Creole, Hmong, Korean, Polish, Portuguese, Russian, Somali, and Vietnamese.

Reminder for Health Care Professionals: The Bright Futures Tool and Resource Kit, 2nd Edition is available as an online access product. For more detailed information about the Toolkit, visit shop.aap.org . To license the Toolkit to use the forms in practice and/or incorporate them into an Electronic Medical Record System, please contact AAP Sales .

Parent Educational Handouts

Infancy visits.

3 to 5 Day Visit

1 Month Visit

2 Month Visit

4 Month Visit

6 Month Visit

9 Month Visit

Early childhood visits.

12 Month Visit

15 Month Visit

18 Month Visit

2 Year Visit

2.5 Year Visit

3 Year Visit

4 Year Visit

Parent and patient educational handouts, middle childhood visits.

5-6 Year Visit

7-8 Year Visit

7-8 Year Visit - For Patients

9-10 Year Visit

9-10 Year Visit - For Patients

Adolescent visits.

11-14 Year Visit

11-14 Year Visit - For Patients

15-17 Year Visit

15-17 Year Visit - For Patients

18-21 Year Visit - For Patients

Last updated.

American Academy of Pediatrics

Family Life

AAP Schedule of Well-Child Care Visits

Parents know who they should go to when their child is sick. But pediatrician visits are just as important for healthy children.

The Bright Futures /American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP) developed a set of comprehensive health guidelines for well-child care, known as the " periodicity schedule ." It is a schedule of screenings and assessments recommended at each well-child visit from infancy through adolescence.

Schedule of well-child visits

- The first week visit (3 to 5 days old)

- 1 month old

- 2 months old

- 4 months old

- 6 months old

- 9 months old

- 12 months old

- 15 months old

- 18 months old

- 2 years old (24 months)

- 2 ½ years old (30 months)

- 3 years old

- 4 years old

- 5 years old

- 6 years old

- 7 years old

- 8 years old

- 9 years old

- 10 years old

- 11 years old

- 12 years old

- 13 years old

- 14 years old

- 15 years old

- 16 years old

- 17 years old

- 18 years old

- 19 years old

- 20 years old

- 21 years old

The benefits of well-child visits

Prevention . Your child gets scheduled immunizations to prevent illness. You also can ask your pediatrician about nutrition and safety in the home and at school.

Tracking growth & development . See how much your child has grown in the time since your last visit, and talk with your doctor about your child's development. You can discuss your child's milestones, social behaviors and learning.

Raising any concerns . Make a list of topics you want to talk about with your child's pediatrician such as development, behavior, sleep, eating or getting along with other family members. Bring your top three to five questions or concerns with you to talk with your pediatrician at the start of the visit.

Team approach . Regular visits create strong, trustworthy relationships among pediatrician, parent and child. The AAP recommends well-child visits as a way for pediatricians and parents to serve the needs of children. This team approach helps develop optimal physical, mental and social health of a child.

More information

Back to School, Back to Doctor

Recommended Immunization Schedules

Milestones Matter: 10 to Watch for by Age 5

Your Child's Checkups

- Bright Futures/AAP Recommendations for Preventive Pediatric Health Care (periodicity schedule)

Skip to content

Why Well-Child Visits Matter

Published on May 02, 2023

Primary Care Locations

Don't fall behind on your child's routine care — a minor issue today could become a major problem tomorrow.

Well-child visits allow your pediatrician to examine your child holistically, assess their physical and emotional needs, support their growth and development, and intervene quickly if any issues arise.

What are the risks of skipping well-child visits?

If your child is healthy, it can be easy to let well visits fall by the wayside. While those annual checkups may seem like just another thing to fit into your family’s hectic schedule, they play a crucial role in preventing future problems.

Find a CHOP Pediatrician

CHOP Primary Care practices, located throughout southeastern Pennsylvania and Southern New Jersey, provide convenient access to primary health and wellness services for children close to home.

Well visits are essential to ensure your child gets the required vaccinations to attend school, go to daycare and participate in sports. Visiting the pediatrician when your child is well also provides you with an opportunity to ask questions – and get expert answers – about your child’s health, development and well-being. Delaying these visits can put your child at greater risk of illness or delay needed interventions. For example, many common developmental delays are discovered during routine checkups with pediatricians – early intervention makes a big difference in getting your child the support they need before something small turns into a bigger issue.

What to expect at a well-child visit

During an annual wellness visit, your child's pediatrician will:

- Determine if your child is meeting growth and developmental milestones for their age.

- Evaluate your child's vision and hearing for anything out of the ordinary – it's important to catch these issues early.

- Ask about sudden changes in your child's usual activities, mood and overall health.

- Assess your child's mental health, and ask questions about how they are coping with school, friends, family and any other outside influences.

- Provide immunizations for childhood diseases and common conditions that affect children or young adults, such as measles and HPV.

- Give sports physicals to children who want to want to participate in competitive sports at school or in the community.

- Get to know your child: their diet, sleeping patterns, nutrition, social interactions, behavior and stress levels

- Help your child establish healthy habits and provide tips for families to reinforce these at home.

- Provide age- and behavior-based counseling for teens on topics such as driver safety, depression and drug or alcohol use.

- Check in on how your family is doing and identify any supportive resources or advice related to navigating daily life.

What are the ages for well-child visits?

A standard well-child visit schedule spans from infancy through adolescence, and includes checkups at the following ages:

- In your baby’s first year: Newborn visit (3-5 days after birth), at 1 month old, 2 months, 4 months, 6 months, 9 months, and at 12 months

- 11-14 years

- 15-17 years

- 18-21 years

Your pediatrician can be a trusted partner at every age and stage of your child’s development.

Contributed by: Lisa Biggs, MD

Stay in Touch

Are you looking for advice to keep your child healthy and happy? Do you have questions about common childhood illnesses and injuries? Subscribe to our Health Tips newsletter to receive health and wellness tips from the pediatric experts at Children's Hospital of Philadelphia, straight to your inbox. Read some recent tips .

With our patient portal you can schedule appointments, access records, see test results, ask your care provider questions, and more.

Subscribe to Health Tips

Subscribe to our Health Tips enewsletter to receive health and wellness tips from the pediatric experts at CHOP.

You Might Also Like

A Dose of Prevention

Learn why vaccinations are important for kids and the community, and what to do if you missed a vaccine and need to get back on track.

Preparing for an Annual Well Visit

Being properly prepared for annual well visits is a great way to get the most out of each appointment with your pediatrician.

How to Have a Productive Video Visit

If your child is scheduled for an online doctor’s appointment, read these tips to get the most out of your visit.

Select Your Interests

Customize your JAMA Network experience by selecting one or more topics from the list below.

- Academic Medicine

- Acid Base, Electrolytes, Fluids

- Allergy and Clinical Immunology

- American Indian or Alaska Natives

- Anesthesiology

- Anticoagulation

- Art and Images in Psychiatry

- Artificial Intelligence

- Assisted Reproduction

- Bleeding and Transfusion

- Caring for the Critically Ill Patient

- Challenges in Clinical Electrocardiography

- Climate and Health

- Climate Change

- Clinical Challenge

- Clinical Decision Support

- Clinical Implications of Basic Neuroscience

- Clinical Pharmacy and Pharmacology

- Complementary and Alternative Medicine

- Consensus Statements

- Coronavirus (COVID-19)

- Critical Care Medicine

- Cultural Competency

- Dental Medicine

- Dermatology

- Diabetes and Endocrinology

- Diagnostic Test Interpretation

- Drug Development

- Electronic Health Records

- Emergency Medicine

- End of Life, Hospice, Palliative Care

- Environmental Health

- Equity, Diversity, and Inclusion

- Facial Plastic Surgery

- Gastroenterology and Hepatology

- Genetics and Genomics

- Genomics and Precision Health

- Global Health

- Guide to Statistics and Methods

- Hair Disorders

- Health Care Delivery Models

- Health Care Economics, Insurance, Payment

- Health Care Quality

- Health Care Reform

- Health Care Safety

- Health Care Workforce

- Health Disparities

- Health Inequities

- Health Policy

- Health Systems Science

- History of Medicine

- Hypertension

- Images in Neurology

- Implementation Science

- Infectious Diseases

- Innovations in Health Care Delivery

- JAMA Infographic

- Law and Medicine

- Leading Change

- Less is More

- LGBTQIA Medicine

- Lifestyle Behaviors

- Medical Coding

- Medical Devices and Equipment

- Medical Education

- Medical Education and Training

- Medical Journals and Publishing

- Mobile Health and Telemedicine

- Narrative Medicine

- Neuroscience and Psychiatry

- Notable Notes

- Nutrition, Obesity, Exercise

- Obstetrics and Gynecology

- Occupational Health

- Ophthalmology

- Orthopedics

- Otolaryngology

- Pain Medicine

- Palliative Care

- Pathology and Laboratory Medicine

- Patient Care

- Patient Information

- Performance Improvement

- Performance Measures

- Perioperative Care and Consultation

- Pharmacoeconomics

- Pharmacoepidemiology

- Pharmacogenetics

- Pharmacy and Clinical Pharmacology

- Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation

- Physical Therapy

- Physician Leadership

- Population Health

- Primary Care

- Professional Well-being

- Professionalism

- Psychiatry and Behavioral Health

- Public Health

- Pulmonary Medicine

- Regulatory Agencies

- Reproductive Health

- Research, Methods, Statistics

- Resuscitation

- Rheumatology

- Risk Management

- Scientific Discovery and the Future of Medicine

- Shared Decision Making and Communication

- Sleep Medicine

- Sports Medicine

- Stem Cell Transplantation

- Substance Use and Addiction Medicine

- Surgical Innovation

- Surgical Pearls

- Teachable Moment

- Technology and Finance

- The Art of JAMA

- The Arts and Medicine

- The Rational Clinical Examination

- Tobacco and e-Cigarettes

- Translational Medicine

- Trauma and Injury

- Treatment Adherence

- Ultrasonography

- Users' Guide to the Medical Literature

- Vaccination

- Venous Thromboembolism

- Veterans Health

- Women's Health

- Workflow and Process

- Wound Care, Infection, Healing

- Download PDF

- Share X Facebook Email LinkedIn

- Permissions

The Well-Child Visit

- Original Investigation Adolescent Preventive Care and the Affordable Care Act Sally H. Adams, PhD; M. Jane Park, MPH; Lauren Twietmeyer, MPH; Claire D. Brindis, DrPH; Charles E. Irwin Jr, MD JAMA Pediatrics

Whatever name you use—check-up, well-child visit, or health supervision visit—these are important.

The benefits of well-child visits include tracking your child’s growth and development. Your pediatrician will review your child’s growth since the last visit and talk with you about your child’s development. These visits are a time to review and discuss each of the important areas of your child’s development, including physical, cognitive, emotional, and social development. Pediatricians often use a resource called Bright Futures to assess and guide discussions with parents about child development. Parents can access Bright Futures to review information relevant to their child’s age using the website at the bottom of this page.

Another benefit of a well-child visit is the opportunity to talk about prevention. For many children in the United States, the most common cause of harm is a preventable injury or illness. The well-child visit is an opportunity to review critical strategies to protect your child from injury, such as reviewing car seat use and safe firearm storage. The well-child visit is an opportunity to ensure your child is protected from infectious diseases by reviewing and updating his or her immunizations. If there is a family history of a particular illness, parents can discuss strategies to prevent that illness for their child. Healthy behaviors are important to instill at a young age, and the well-child visit is a time to review these important behaviors, such as sleep, nutrition, and physical activity.

During the teenage years, well-child visits offer adolescents an opportunity to take steps toward independence and responsibility over their own health behaviors. Every well-child visit with a teenager should include time spent alone with the pediatrician so that the adolescent has the opportunity to ask and answer questions about their health. Adolescent visits provide an opportunity for teenagers to address important questions, including substance use, sexual behavior, and mental health concerns.

Physical examination and screening tests are also a part of the well-child visit. Your child’s visit may include checking blood pressure level, vision, or hearing. Your pediatrician will do a physical examination, which may include listening to the lungs and feeling the abdomen. Screening tests can include tests for anemia, lead exposure, or tuberculosis. Some screening, such as for depression or anxiety, is done using a paper form or online assessment.

How Parents and Kids Can Get the Most Out of a Well-Child Visit

Ideally, schedule the visit ahead of time so that there is time to complete any required school or sports forms. Some parents schedule these visits to correspond with their children’s birthdays, while others schedule these during summer months to prepare for the start of a new school year.

Make a list of topics you want to discuss with your child’s pediatrician, such as development, behavior, sleep, eating, or prevention. Bring your top 3 to 5 questions with you to the visit. As your child gets older, ask your child to contribute any questions he or she would like to ask.

When going to the visit, it may be helpful to bring your child’s immunization record, a list of questions, or any school or sports forms you need completed.

For More Information

https://www.healthychildren.org/English/family-life/health-management/Pages/Well-Child-Care-A-Check-Up-for-Success.aspx .

Published Online: November 6, 2017. doi:10.1001/jamapediatrics.2017.4041

Conflict of Interest Disclosures: None reported.

See More About

Moreno MA. The Well-Child Visit. JAMA Pediatr. 2018;172(1):104. doi:10.1001/jamapediatrics.2017.4041

Manage citations:

© 2024

Artificial Intelligence Resource Center

Pediatrics in JAMA : Read the Latest

Browse and subscribe to JAMA Network podcasts!

Others Also Liked

- Register for email alerts with links to free full-text articles

- Access PDFs of free articles

- Manage your interests

- Save searches and receive search alerts

Catch Up on Well-Child Visits and Recommended Vaccinations

Many children missed check-ups and recommended childhood vaccinations over the past few years. CDC and the American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP) recommend children catch up on routine childhood vaccinations and get back on track for school, childcare, and beyond.

Making sure that your child sees their doctor for well-child visits and recommended vaccines is one of the best things you can do to protect your child and community from serious diseases that are easily spread.

Well-Child Visits and Recommended Vaccinations Are Essential

Well-child visits and recommended vaccinations are essential and help make sure children stay healthy. Children who are not protected by vaccines are more likely to get diseases like measles and whooping cough . These diseases are extremely contagious and can be very serious, especially for babies and young children. In recent years, there have been outbreaks of these diseases, especially in communities with low vaccination rates.

Well-child visits are essential for many reasons , including:

- Tracking growth and developmental milestones

- Discussing any concerns about your child’s health

- Getting scheduled vaccinations to prevent illnesses like measles and whooping cough (pertussis) and other serious diseases

It’s particularly important for parents to work with their child’s doctor or nurse to make sure they get caught up on missed well-child visits and recommended vaccines.

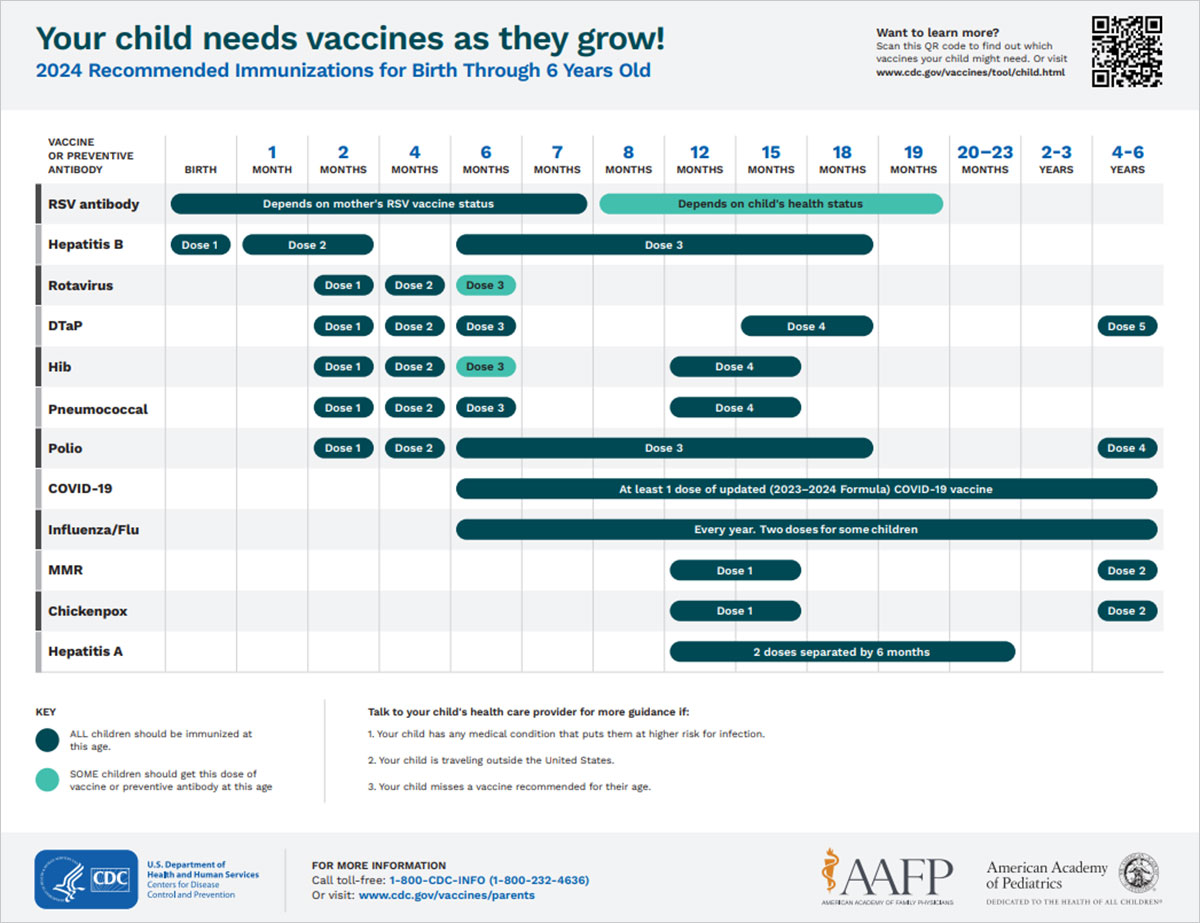

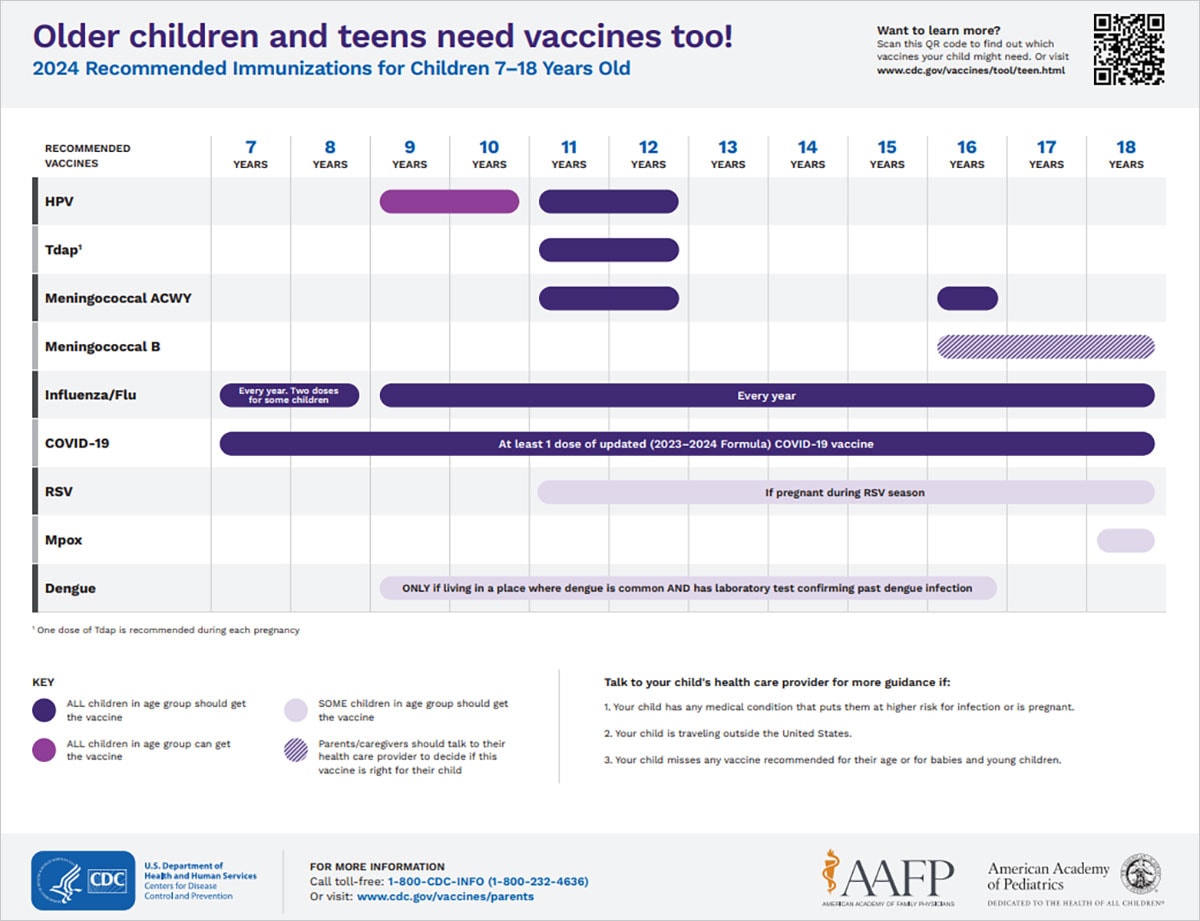

Routinely Recommended Vaccines for Children and Adolescents

Getting children and adolescents caught up with recommended vaccinations is the best way to protect them from a variety of vaccine-preventable diseases . The schedules below outline the vaccines recommended for each age group.

See which vaccines your child needs from birth through age 6 in this easy-to-read immunization schedule.

See which vaccines your child needs from ages 7 through 18 in this easy-to-read immunization schedule.

The Vaccines for Children (VFC) program provides vaccines to eligible children at no cost. This program provides free vaccines to children who are Medicaid-eligible, uninsured, underinsured, or American Indian/Alaska Native. Check out the program’s requirements and talk to your child’s doctor or nurse to see if they are a VFC provider. You can also find a VFC provider by calling your state or local health department or seeing if your state has a VFC website.

COVID-19 Vaccines for Children and Teens

Everyone aged 6 months and older can get an updated COVID-19 vaccine to help protect against severe illness, hospitalization and death. Learn more about making sure your child stays up to date with their COVID-19 vaccines .

- Vaccines & Immunizations

Exit Notification / Disclaimer Policy

- The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) cannot attest to the accuracy of a non-federal website.

- Linking to a non-federal website does not constitute an endorsement by CDC or any of its employees of the sponsors or the information and products presented on the website.

- You will be subject to the destination website's privacy policy when you follow the link.

- CDC is not responsible for Section 508 compliance (accessibility) on other federal or private website.

Health Library 6 Month Well-Child Visit

Find another condition or treatment, healthy baby development and behavior.

Below are milestones most babies will reach between now and 9 months old. Talk with your doctor at your baby’s next well-visit if your baby is not yet reaching these milestones or there are skills your baby no longer shows each day.

Social and Emotional Milestones

- Is shy, clingy or fearful around strangers

- Shows several facial expressions, like happy, sad, angry or surprised

- Looks when you call their name

- Reacts when you leave (looks, reaches for you or cries)

- Smiles or laughs when you play peek-a-boo

Language and Communication Milestones

- Makes different sounds like “mamama” and “bababa”

- Lifts arms to be picked up

Thinking and Learning Milestones

- Looks for objects when dropped out of sight (like a spoon or toy)

- Bangs two things together

Physical Development Milestones

- Gets to a sitting position by themselves

- Moves things from one hand to the other hand

- Uses fingers to “rake” food toward themselves

- Sits without support

Healthy Ways to Help Your Baby Learn and Grow

Development.

- Hold your baby up while they sit and learn to balance on their own. Encourage them by giving a toy to look at and letting them look around.

- Teach your baby social skills by copying your baby when they smile and make sounds.

- Point to things your baby looks at and name them (for example, a book, tree or cup). Talk with your baby by repeating the sounds they make.

- Sing and play music for your baby. Read together every day, pointing to items in the book and using simple words to talk about the pictures.

- Encourage your baby to crawl, scoot and roll on the ground by placing toys a little out of reach.

- Play games such as peek-a-boo and patty-cake.

- Hold and cuddle with your baby often, giving praise and lots of loving attention.

- If your baby becomes fussy, take a break from whatever you’re doing and offer comfort. Help your baby learn to calm themselves by rocking, singing, sucking their fingers or a pacifier, or holding a favorite stuffed animal.

- Breast milk or infant formula should continue to be your baby’s main source of nutrition until 1 year of age.

- Look for signs your baby is ready for soft foods. Before eating soft foods, your baby should be able to sit with support, have good head and neck control, show interest in the foods you eat, and open their mouth for the spoon.

- When starting new foods, introduce one, single-ingredient food at a time. Wait three-five days before introducing another new food to make sure your baby doesn’t have a reaction. Use a spoon to give food, and don’t mix infant foods in the baby’s bottle. Learn more about introducing solid foods to your baby , including appropriate beginner foods and portion sizes.

- Introduce your baby to a cup with a small amount of water, breast milk or formula.

- Clean your baby’s gums and teeth twice a day with a soft cloth or toothbrush. Use a small amount of fluoride toothpaste, no more than a grain of rice.

- Avoid giving your baby a bottle in the crib. Never prop the bottle.

- Avoid juice.

- Your baby may sleep 12–16 hours each night, with two-three naps during the day. Remember to lay your baby on its back to sleep.

- Calm or rock your baby before bed until they are tired. It is good for babies to be drowsy when put down for bedtime, but allow them to fall asleep on their own.

- Follow a nighttime routine to help your baby feel safe and secure before sleep.

Vehicle Safety

- Use a rear-facing car seat in the backseat of your vehicle. Learn more about car seat safety and installation.

- Never leave your baby alone in a car. Practice safe behaviors that prevent you from ever forgetting your baby in the car, like putting your purse or cell phone in the backseat.

- Learn more about the dangers of hot cars and how to keep your child safe.

Home Safety

- Learn first aid for choking and cardiopulmonary resuscitation (CPR).

- Cover electrical outlets and block stairs with a small gate.

- Lock up medicines and cleaning supplies. Save the Poison Help Line number (1-800-222-1222) in all phones.

- Keep cords, latex balloons, plastic bags and small objects like coins, marbles and batteries away from your child.

- Never leave your baby alone in the tub, near water or in high places like a changing table, bed or couch.

- Your baby is becoming more active and learning to move. Don’t wait to baby-proof your home. Learn more about home safety.

This information is meant to support your visit with your child’s doctor. It should not take the place of the advice of your pediatrician.

Sources: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Bright Futures (4th Edition) by the American Academy of Pediatrics

Last Updated 06/2023

Cincinnati Children’s has primary care services at locations throughout Greater Cincinnati.

Translations

- Spanish Translation

Connect With Us

3333 Burnet Avenue, Cincinnati, Ohio 45229-3026

© 1999-2024 Cincinnati Children's Hospital Medical Center. All rights reserved.

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

- v.15(9); 2023 Sep

- PMC10576162

Analyzing Best Practices for Pediatric Well-Child Clinic Visits in the United States for Children Aged Three to Five Years: A Review

Okelue e okobi.

1 Family Medicine, Larkin Community Hospital Palm Springs Campus, Miami, USA

2 Family Medicine, Medficient Health Systems, Laurel, USA

3 Family Medicine, Lakeside Medical Center, Belle Glade, USA

Patience F Akahara

4 Family Medicine, Inglewood Medical Centre, Edmonton, CAN

Onyinyechukwu B Nwachukwu

5 Neurosciences and Psychology, California Institute of Behavioral Neurosciences & Psychology, Fairfield, USA

6 Family Medicine, American International School of Medicine Georgetown, Guyana, USA

Thelma O Egbuchua

7 Pediatrics and Neonatology, Delta State University Teaching Hospital, Oghara, NGA

Olamide O Ajayi

8 Internal Medicine, Obafemi Awolowo College of Health Sciences, Olabisi Onabanjo University, Sagamu, NGA

Kelechukwu P Oranu

9 Obstetrics and Gynecology, Kenechukwu Specialist Hospital and Maternity Enugu, Enugu, NGA

Ifreke U Ibanga

10 Pediatrics, Thompson General Hospital, Manitoba, CAN

Inadequate routine healthcare check-up visits for children aged three to five years impose substantial economic and social burdens due to morbidity and mortality. The absence of regular well-child visits and vaccinations leads to avoidable diseases, underscoring the need for a renewed emphasis on childhood immunizations and check-ups. Out of 160 articles initially screened after removing duplicates, 45 were chosen for full-text review following initial title and abstract screening by two independent reviewers. Afterward, 20 studies met the predefined inclusion criteria during the final assessment of full-text articles, and data were systematically extracted from these selected studies using standardized forms to ensure accuracy and consistency. Well-child visits promote holistic development, health, and well-being in children aged three to five years. Following established guidelines and evidence-based practices, healthcare professionals provide assessments, vaccinations, and guidance for a healthy future. Despite challenges, well-child visits are vital for preventive care, empowering informed decisions for children's growth and development. The benefits of well-child visits encompass growth monitoring, anticipatory guidance, and preventive measures, crucial for children with chronic illnesses. Key components include comprehensive assessments, developmental screenings, vision and hearing evaluations, immunizations, health education, and counseling. In the case of juvenile diabetes, parental education is paramount. Parents need to understand the intricacies of insulin administration, including proper dosage calculation based on glucose measurements, meal planning, and the importance of timing insulin injections. Implementing guidelines and principles by organizations such as Bright Futures and the American Academy of Pediatrics ensures holistic care, parent involvement, and evidence-based practices. This review explores best practices and guidelines for such visits, emphasizing their role in monitoring and promoting children's development.

Introduction and background

Pediatric-associated morbidity and mortality resulting from inadequate routine healthcare check-up visits impose a considerable national economic and social burden worldwide, including in the United States. The data collected from medical check-up records from January 2019 to December 2020 revealed that the risk of disease-related adverse outcomes in a population is higher if routine non-healthcare check-up visits are ignored [ 1 - 4 ]. For example, missed vaccinations have been identified as a significant contributor to the rise of pediatric vaccine-preventable illnesses in the United States. According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), millions of children in the United States are under-vaccinated or unvaccinated against preventable diseases [ 1 - 5 ]. The CDC website provides a recommended immunization schedule for children from birth through 18 years of age, and parents can check with their child's healthcare provider to ensure that their child is up to date on vaccinations [ 1 - 3 ]. However, missed well-child visits (WCVs) have resulted in significant declines in vaccination coverage in children at all milestone ages [ 1 ]. The decline in vaccination coverage has markedly increased the risk of vaccine-preventable diseases in children, including measles, polio, and pertussis [ 1 , 2 ]. Re-prioritizing childhood immunizations and well-visits can prevent the re-emergence of vaccine-preventable diseases, and it is essential that parents and care providers prioritize children's well-child schedule to prevent the rise of pediatric-preventable illnesses in the United States. In addition to that, re-prioritizing childhood immunizations has a far-reaching impact beyond the prevention of vaccine-preventable diseases. This, in turn, can help prevent non-vaccine-preventable diseases by alleviating the burden on healthcare systems, reducing the risk of hospital-acquired infections, and improving overall population health [ 1 - 5 ].

Also, these absences of regular and full body healthcare check-ups for children aged three to five years can lead to undetected health issues, delayed interventions, and potentially fatal consequences [ 2 - 6 ]. This translates into increased medical costs, reduced productivity, and an emotional toll on families. The economic impact encompasses direct medical expenses for treating preventable illnesses, emergency care, and hospitalization, often straining healthcare resources. Moreover, the long-term consequences of inadequate health supervision during these critical developmental years can lead to reduced educational attainment, hindered workforce participation, and a perpetuated cycle of health disparities [ 5 - 8 ]. As a result, investing in and promoting routine healthcare check-up visits for pediatric populations is essential not only for safeguarding the well-being of the younger generation but also for alleviating the economic and social ramifications that arise from preventable disease burdens and loss of life [ 1 - 9 ].

Pediatric WCVs are marked by significant changes in speech and language proficiency, as well as the refinement of fine and gross motor skills. Their burgeoning social interactions and cognitive abilities further underscore the importance of this developmental phase. Regular WCVs during this stage assume a vital role in assessing a child's progress, offering a valuable chance to identify any potential deviations from the expected trajectory and intervene promptly if necessary [ 8 - 10 ].

Moreover, the preschool years witness the emergence of emotional and behavioral skills in children, a domain equally crucial to their holistic development. Within this context, WCVs serve as a platform for healthcare providers to engage with parents, addressing concerns related to behavior, furnishing strategies for managing behavioral obstacles, and discerning subtle signs of emotional or psychological challenges that might warrant attention. Adding to the array of advantages inherent in these WCVs, it is noteworthy that this age range coincides with a critical juncture for immunizations. The routine check-ups between three and five years of age routinely encompass pivotal immunizations that bolster a child's immunity, safeguarding them against a spectrum of severe diseases, and forging a shield of protection that will serve them well into the future [ 3 - 6 , 11 - 14 ].

This comprehensive review analyzes the best practices and guidelines for pediatric WCVs in children aged three to five years. We will explore the importance and benefits of these visits and the components that make up a successful visit. Additionally, we will examine the best practices and potential challenges associated with implementing them and review the guidelines and principles that should be followed during these visits. By doing so, we hope to provide a thorough understanding of the importance of these visits and the relationship between continuity, quality of care, and long-term health outcomes that can guide healthcare providers in delivering the most effective care to pediatric patients, ultimately leading to improved health and well-being in the years to come.

Methods and Materials, and Literature Search

For the present systematic review, an in-depth and comprehensive literature search was conducted on various online databases, including PubMed, Science Direct, Google Scholar, Embase, and Cochrane Library, for peer-reviewed and English-language articles published between 2000 and 2023. The search used various combinations of MeSh terms: “Well child visit,” “well child clinic,” “pediatric healthcare check-up visit,” and “well-baby care,” “preventive care,” and “primary care,” and Boolean operators (AND, OR, NOT) and parentheses to specify various combinations of operations in PubMed, Science Direct, Google Scholar, Embase, Cochrane Library, and HINARI: (1) PubMed (All terms with OR): (“Well child visit” OR “well child clinic” OR “pediatric healthcare check-up visit” OR “well-baby care”) AND (“preventive care” OR “primary care”); (2) Science Direct (Well-child visit and preventive care): (“Well-child visit” OR “pediatric healthcare check-up visit” OR “well-baby care”) AND “preventive care”; (3) Google Scholar (primary care and well-child visit): (Well child visit” OR “pediatric healthcare check-up visit” OR “well-baby care”) AND “primary care”; (4) Embase (Well-child visit and NOT primary care): (“Well child visit” OR “pediatric healthcare check-up visit” OR “well-baby care”) NOT “primary care”; (5) Cochrane Library (Well-child visit OR well-child clinic): (“Well child visit” OR “well-child clinic”) AND (“preventive care” OR “primary care”). We also used exact phrase search, and these combinations allowed us to specify different search criteria related to child healthcare visits, preventive care, and primary care. The Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA; Figure Figure1) 1 ) was then used as the preferred guideline for consistency. To locate the articles, we employed keywords that included “well child clinic,” “pediatric healthcare check-up visit,” and “well-baby care,” alongside MeSH terms “preventive care” and “primary care.” The references of the included studies were searched to identify additional articles. The articles sought for were mainly those that analyzed the best practices related to well-child clinic visits, those that explored the significance of such clinical visits, and those that reviewed the components making up successful and effective well-child clinic visit, as well as the best practices and challenges linked to execution of best practices guidelines and principles. The present systematic review has focused on the best practices and guidelines for well-child clinic visit for children aged three to five years. To attain the objectives, the interventions are to be practice-based and applicable to well-child clinic care delivery.

PRISMA, Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

For the current systematic review, we excluded studies that had focused on the evaluation of the process of quality improvement in best practices in well-child clinic visits without acknowledging specific practice changes to child care delivery; articles that focused on one topic in well-child care as opposed to tackling the different aspects of well-child clinic practices more generally; articles that were published before 2010 and those that were published in languages other than English, and studies that focused on tackling changes in well-child clinic without tackling the issue of changes in service delivery.

A total of 160 articles were screened for primary screening (title and abstract review) after removing duplicates. Two independent reviewers conducted the initial screening of titles and abstracts to identify potentially relevant articles. After the initial screening, a total of 45 studies were included for secondary screening or full-text review. Full-text articles were obtained for studies that met the initial screening criteria or where there was uncertainty. The full-text articles were then assessed for final inclusion based on the predefined inclusion and exclusion criteria, and, finally, 20 studies were included in this review for data extraction. Data were systematically extracted from the selected studies and assessed using standardized forms to ensure consistency and accuracy.

Consequently, the studies included in this review (Table (Table1) 1 ) were observational studies, randomized controlled trials, and systematic reviews, which included child participants aged zero to five years (with focus on three to five years), and whose findings are directly related to delivery and reception of well-child clinic services, care quality, and child health and development outcomes. We also independently screened the studies and titles with the objective of excluding articles that were duplicated and were irrelevant to the study objectives. The abstracts of studies were also screened using a brief and structured screening tool with the objective of establishing if the selected article satisfied the inclusion criteria, including the topic being studied, the study design, target population, sample size, and study location. We also reviewed the abstract screening outcomes, even as disagreements were solved through general consensus. For the accepted abstracts, retrieval of full texts was conducted, even as a structured form was employed in the extraction of data pertaining to the study design, methodology, results, and findings.

EPDS, Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale; PPD, postpartum depression; PRO, patient-reported outcome; RCT, randomized controlled trial; WCC, well-child clinic; WCV, well-child visit

Quality assessment

The assessment of the included studies’ quality was evaluated using the Joanna Briggs Institute quality assessment tool. The tool scores every publication using the frequency scales that were accorded yes, no, unclear, and not applicable responses. The overall quality score of every study was aptly calculated based on the total amount of positive scores received.

An overview of the importance of pediatric well-child visits for children aged three to five years

The importance of a pediatric WCV for children aged three to five years should not be underestimated. These visits provide an opportunity for the physician to screen for medical issues, provide anticipatory guidance, and promote good health for the child [ 6 ]. They also allow primary care physicians to establish a bond with the parents or caregivers and to prioritize interventions with the strongest evidence for good patient-oriented outcomes, such as family social-economic dynamics, assessment and support, and other health-related goals [ 6 ]. Following the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF) and the American Academy of Pediatrics guidelines, immunizations should be updated if necessary, and a one-time vision screening should be carried out between three and five years of age [ 6 ]. Additionally, a head-to-toe examination should be performed, including a review of growth [ 6 ]. During the visit, the physician can answer any questions the parents or caregivers might have and provide age-appropriate guidance [ 6 ]. Furthermore, if any abnormalities are detected, the visit offers the opportunity for further evaluation [ 6 ]. Pediatricians are often parents' main formal counseling source for their children's development and education. Their anticipatory guidance can help improve outcomes in various areas such as infant vocal behavior, parenting skills, infant sleep patterns, parental use of discipline, language development, prevention of falls, home accidents, and auto-passenger injuries [ 7 ]. The WCV is also a chance to use the CDC-recommended growth charts for assessment and to review parent/caregiver-child interactions [ 6 ]. Furthermore, potential signs of abuse should be assessed, and interval growth should be reviewed using appropriate growth charts for height, weight, head circumference, and body mass index [ 6 - 7 ]. Moreover, primary care providers are well-positioned to engage parents and provide referrals to community services during WCVs [ 8 ]. Table Table2 2 shows an overview of the main components of a WCV.

Benefits of a well-child visit for young children

The benefits of WCVs for young children are numerous [ 8 , 9 ]. WCVs enable pediatricians to review a patient's health history, track a child's growth and development, and provide guidance for parents around topics such as nutrition, sleep, and behavioral development [ 10 , 11 ]. Furthermore, studies have shown that the length of a WCV is linked to the amount of unmet needs experienced by a family [ 12 , 13 ]. This is especially pertinent for children with chronic illnesses or special healthcare needs [ 12 ], as pediatric visits are more likely to result in hospital admission than adults [ 14 ]. Additionally, WCVs provide an opportunity to discuss prevention, as in the case of childhood obesity [ 15 ]. To ensure that WCVs are valuable, there should be an agreement between parents and medical professionals about the visit's goals [ 7 ]. Furthermore, physicians should discuss topics such as when to introduce solid foods [ 6 ], as this has implications for a child's long-term health. As a result, WCVs can be incredibly beneficial to young children and their families.

Components of a well-child visit for children aged three to five years

This analysis also provided details of the topics discussed during the visits. These topics were classified into seven categories: secondary prevention, primary prevention, health promotion, development, education, and those focused on the parents and family relationship [ 7 ]. The study was based on 49 visits to five pediatricians for children aged three to five years [ 7 ]. The results showed that the major topics discussed during the visits were illness prevention and education, followed by physical examination and development. Other topics such as health promotion, safety, nutrition, and emotional and mental health were also discussed but in lesser amounts. These results suggest that pediatric providers focus on the primary aspects of a child's physical and mental health, although other topics are often included in the visit. However, this study did not provide specific information about the components of a WCV for children aged three to five years [ 7 ]. This means that it is still necessary to understand the specific topics discussed during a WCV to effectively assess a child's health. Therefore, further studies are needed to provide more information about the components of a WCV for children aged three to five years.

Best practices for pediatric well-child visits

A recent study assessed the effectiveness of the Improved Care for Moms and Babies (ICC) model on maternal depression screening and other health behaviors discussed during pediatric WCVs. The study gathered information from mothers who had accompanied their children to WCVs at ages 12 and 24 months [ 15 ]. The survey included questions about health history, behaviors, and whether the physician discussed maternal depression, tobacco use, family planning, and folic acid supplementation [ 16 ]. The results of the study showed that the ICC model had improved the way maternal depression was being addressed during WCVs. However, best practices for screening, referral processes, and documentation related to PPD screening during WCVs still require further study [ 17 ]. This is especially important, as screening for postpartum depression in mothers is recommended during WCVs for young children [ 17 ].

Best practices implemented in a well-child visit

Best practices for WCVs are those that provide the most patient-oriented outcomes, such as immunizations, postpartum depression screening, and vision screening [ 18 ]. The American Academy of Pediatrics has created guidelines for WCVs, known as the periodicity schedule, and they recommend scheduled WCVs [ 19 ]. A study was conducted to determine the impact of the intervention on illness visits between WCVs [ 10 ]. The results showed that there were few differences between the two study arms, but a chart review showed that intervention children had fewer illness visits [ 10 ]. Pediatric WCVs also provide an opportunity to address psychosocial issues and developmental assessments [ 20 , 21 ], and there is wide variation in practice patterns regarding screening [ 22 ]. As far as the duration of WCVs, they are usually short; therefore, strategies for addressing the time devoted to WCVs must be considered [ 23 ]. Finally, it is important to understand the best practice of screening, education, and referral processes for addressing psychosocial issues during WCVs [ 16 ], as they are a significant part of pediatric office visits [ 24 ].

Potential challenges to implementing these best practices in a well-child visit

Additionally, the potential challenges to implementing best practices in a WCV must be acknowledged [ 18 ]. For instance, the lack of evidence-based practices can lead to uncertainty about how best to use the limited time available [ 23 ]. Furthermore, the Committee on Practice and Ambulatory Medicine of the American Academy of Pediatrics has offered a periodicity schedule to recommend scheduled WCVs [ 19 ]. In a study to assess the differences between the interventions and the control arms, it was found that children in the intervention group had fewer illness visits between WCVs than control children [ 10 ]. This points to the importance of further understanding best practices for screening, education, and referral during the WCVs [ 16 ]. In this regard, research has revealed that 11.6% of the 483 WCVs were with children between 18 and 36 months of age [ 24 ]. Moreover, wide variations in practice patterns have been observed with some using a parent questionnaire for all WCVs and some using formal screens only at specific ages [ 22 ]. In addition, there is growing interest in understanding the practices of pediatric well-child care internationally [ 21 ] and exploring promising strategies for screening during WCVs [ 17 ]. Finally, there is a need to consider the ethical and legal dimensions of the boundaries of pediatric care [ 20 ].

Guidelines and principles for pediatric well-child visits

The subject of pediatric WCVs has been studied, and a number of guidelines have been developed to ensure that young children receive the best care. Studies have looked into adherence to pediatric WCV recommendations [ 25 ], and the standards and principles of Bright Futures [ 26 ]. In addition, similarities in approach to child health with periodic visits and anticipatory guidance have been seen abroad [ 21 ]. Guidelines recommend scheduled WCVs, detailing the schedule and content of care [ 19 ]. This includes preventive care such as guidance directed by a physician [ 27 ], and screening tests such as hearing screening [ 28 ]. However, further work is needed to optimize well child care [ 29 ], and a study found that a schedule with fewer visits had no detrimental effect on child health [ 30 ]. Pediatric WCVs are essential for the health and well-being of children, and research has been conducted to ensure that these visits are up-to-date and provide the best possible care.

Implementing guidelines and principles in a well-child visit

Therefore, the implementation of established guidelines and principles for WCVs is necessary [ 25 ]. The standards and principles of Bright Futures and the American Academy of Pediatrics [ 26 ] are similar in their approach of providing periodic visits and anticipatory guidance [ 21 ]. These guidelines and principles are used to define the schedule and content of well-child care [ 19 ], which includes guidance directed by a physician and preventive issues [ 17 ]. For example, screening tests for children who cannot fully participate are recommended [ 28 ]. Furthermore, research has shown that a schedule with fewer visits has no detrimental effect on child health [ 30 ]. Even though these articles provide a proof of principle, additional work is necessary to optimize well-child care [ 20 ]. Table Table3 3 shows an overview of the basic principles fostering a WCV.

Potential challenges to implementing these guidelines and principles in a well-child visit

Challenges to implementing effective WCV guidelines and principles arise from multiple areas [ 25 ]. For instance, the adherence rate of WCV recommendations may be lower for certain children [ 26 ]. Various countries have a similar approach to child health, focusing on periodic visits and anticipatory guidance [ 21 ]. The principles of prevention that shape WCV can vary depending on the country [ 19 ]. WCV is the most common type of physician visit for children, and it typically involves guidance from a physician [ 27 ]. For example, some children may have difficulty participating in screening tests [ 28 ]. In addition, further work is needed to optimize WCV, and research has suggested that a schedule with fewer visits may not have a detrimental effect on child health [ 29 ]. While there are suggested approaches for WCV programs, these are intended to be illustrative principles rather than specific programs [ 30 ]. As such, there are multiple potential challenges to implementing WCV guidelines and principles that must be carefully considered.

Study strengths and limitations

The research conducted in this study possesses several strengths. Firstly, the systematic review follows the PRISMA guidelines, ensuring a rigorous and transparent approach to study selection, data extraction, and synthesis. The search strategy utilized a range of global databases, including Web of Science, EMBASE, PubMed, Cochrane Library, HINARI, and Google Scholar, as well as reference list searches, minimizing the risk of missing relevant studies and enhancing the comprehensiveness of the review. The use of Boolean operators and specific keywords contributes to the thoroughness of the search process; however, the debate surrounding the replication of search results using mesh terms, Boolean combinations, and parentheses for precise literature retrieval stems from concerns about sensitivity and specificity. This debate continues due to factors such as the publication rate, retractions in online scholarly articles, and limitations in search algorithms. Additionally, the focus on studies published within a specific timeframe (2000-2023) enables the inclusion of recent and up-to-date evidence, relevant to the current landscape of acute gout treatment. The evolution and progression of best practices in pediatric well-child clinic visits from 2000 to 2023 have been influenced by advancements in healthcare, changes in technology, evolving clinical guidelines, and a growing understanding of child development and preventive care. The systematic approach to data extraction and quality assessment, including the use of the Joanna Briggs Institute quality assessment tool, enhances the credibility of the findings and the overall reliability of the review. Moreover, the analysis of both monotherapy and combination therapy approaches provides a comprehensive understanding of their respective impacts on serum urate levels, gout symptoms, and overall management. By evaluating various outcomes such as serum urate levels, tophi, gout flare rates, and urinary uric acid, the study contributes a holistic perspective on the effectiveness of the different treatment strategies. Overall, these methodological strengths support the reliability and validity of the conclusions drawn from the research.

However, there are some limitations. Firstly, the scope of included studies is limited to those published between 2000 and 2023, potentially excluding relevant earlier studies that could contribute valuable insights to the topic. Moreover, the inclusion criteria focus on observational studies with specific designs and geographic restrictions, which might omit relevant experimental or international studies that could provide a more comprehensive perspective on the subject matter. Secondly, the diversity in methodologies, patient populations, and study quality across the included studies introduces heterogeneity, which can lead to inconsistencies in findings and complicate direct comparisons between the studies. Despite the use of the Joanna Briggs Institute quality assessment tool, variations in study quality could influence the reliability and robustness of the conclusions drawn from the review. Finally, the search for studies was confined to a selection of global databases and conducted exclusively in English. This approach may introduce publication bias; favoring studies with significant findings and excluding studies published in other languages may limit the representation of findings from non-English-speaking regions, ultimately affecting the generalizability of the conclusions derived from the research.

Conclusions

Pediatric WCV for children aged three to five years is a vital part of preventive healthcare, addressing physical, emotional, cognitive, and social development. Evidence-based practices ensure comprehensive assessments, vaccinations, developmental screenings, and guidance, thus nurturing a healthy future. These visits benefit immediate and long-term well-being, enhancing individual and community health.

This review emphasizes the importance of WCVs in screening for medical issues, providing guidance, and promoting health. It underlines bonding between physicians, parents, and caregivers, prioritizing evidence-based interventions. Immunizations and socio-dynamic support are highlighted, emphasizing their relevance in WCVs. These visits also offer opportunities for answering parental questions and giving age-appropriate advice. However, challenges exist in implementing guidelines, especially for children with chronic conditions. Primary care providers are essential in engaging parents and linking them to community services, improving outcomes in areas such as vocal behavior, parenting, and language development.

Further research is required to assess individual components' effectiveness in these visits and address implementation challenges, especially for children aged three to five years. In conclusion, policy changes are crucial to underscore the significance of WCVs and ensure that best practices are consistently followed. These changes can lead to better health outcomes, increased vaccination coverage, improved parental education, and reduced healthcare disparities, ultimately benefiting children and communities as a whole.

Acknowledgments

O.E.O. contributed to the conceptualization of this project and the acquisition of the pieces of literature, played several roles in analyzing the collated works of literature, carefully reviewed them for the correctness of the intellectual content, agreed to be accountable for all aspects of the integrity of the work, and approved the final version. P.F.A. contributed to the design of this work, played a role in the interpretation of the collated literature and writing parts such as the introduction, discussion, and other parts, reviewed it for intellectual accuracy, agreed to be accountable for its integrity and will answer any question that may arise, and provided final approval of the final draft. O.B.N. played a role in creating the manuscript design, collating the works of literature used, analyzing the kinds of literature used, drafting parts of the body and conclusion, agreeing to be responsible for the intellectual accuracy and validity of the work, answering the ensuing questions, and authorizing the final version. T.O.E. substantially contributed to this study concept, was involved in analyzing the collated literature that was reviewed, reviewed its scientific content for correctness, drafted part of the abstract and body, agreed to be accountable for its integrity and to resolve any unfolding issues, and then approved its final version. O.O.A. significantly contributed to the creation of this manuscript by playing a role in the conceptualization, ensuring it was critically reviewed for intellectual content and accuracy, agreeing to resolve any unfolding queries about the work and its integrity, and finally approving the final draft. KPO: played a role in conceptualizing this study; reviewed, analyzed, and drafted parts of the body of the work; ensured its intellectual content is worthy of publication; agreed to be accountable for its integrity and to resolve any queries that may arise; and finally approved the final version. IUI: In addition to conceptualizing and designing the manuscript, this author played a role in synthesizing the works of literature, analyzing the content, creating parts of the original drafts, reviewing subsequent drafts for their intellectual validity and content, agreeing to be accountable for all aspects of the work, and finally approving its final version.

The authors have declared that no competing interests exist.

IMAGES

VIDEO

COMMENTS

Beginning at the 7 year visit, there is both a Parent and Patient education handout (in English and Spanish). For the Bright Futures Parent Handouts for well-child visits up to 2 years of age, translations of 12 additional languages (PDF format) are made possible thanks to the generous support of members, staff, and businesses who donate to the ...

The Bright Futures/American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP) developed a set of comprehensive health guidelines for well-child care, known as the "periodicity schedule." It is a schedule of screenings and assessments recommended at each well-child visit from infancy through adolescence. Schedule of well-child visits. The first week visit (3 to 5 ...

1-800-TRY-CHOP. 1-800-879-2467. Parent and patient handouts from the Bright Futures Tool and Resource Kit address key information for health supervision care from infancy through adolescence.

Immunizations are usually administered at the two-, four-, six-, 12-, and 15- to 18-month well-child visits; the four- to six-year well-child visit; and annually during influenza season ...

Visiting the pediatrician when your child is well also provides you with an opportunity to ask questions - and get expert answers - about your child's health, development and well-being. Delaying these visits can put your child at greater risk of illness or delay needed interventions. For example, many common developmental delays are ...

Children six years and older. Obesity, screening. Children 10 years and older. Skin cancer, counseling to reduce risk. Children 12 years and older. Depression, screening. Sexually active ...

Physical examination and screening tests are also a part of the well-child visit. Your child's visit may include checking blood pressure level, vision, or hearing. Your pediatrician will do a physical examination, which may include listening to the lungs and feeling the abdomen. Screening tests can include tests for anemia, lead exposure, or ...

The Vaccines for Children (VFC) program provides vaccines to eligible children at no cost. This program provides free vaccines to children who are Medicaid-eligible, uninsured, underinsured, or American Indian/Alaska Native. Check out the program's requirements and talk to your child's doctor or nurse to see if they are a VFC provider.

Include at least three servings of calcium (low-fat or fat-free dairy) and five servings of fruits and vegetables each day. Limit sugary foods, candy, soft drinks and juice. Help your child brush their teeth twice each day (after breakfast and before bed) and floss their teeth once per day. Take your child to the dentist twice each year.

September 15, 2018 WELL˜CHILD ISITS. -

Development. Hold your baby up while they sit and learn to balance on their own. Encourage them by giving a toy to look at and letting them look around. Teach your baby social skills by copying your baby when they smile and make sounds. Point to things your baby looks at and name them (for example, a book, tree or cup).

Patient Education and Counseling Bailey-Davis et al Comparing enhancements to well-child visits in the prevention of obesity: ENCIRCLE cluster-randomized controlled trial ... Well-child visits should be scheduled according to the recommended timeline established by pediatric health organizations, typically occurring annually.

Well-Child Visit Handouts. Parent and patient handouts from the Bright Futures Tool and Resource Kit, 2nd Edition, address key information for health supervision care from infancy through adolescence.Bright Futures is a national health care promotion and disease prevention initiative that uses a developmentally based approach to address children's health care needs in the context of family ...