This Was The First Documented Starlight Tour Case

So-called Starlight Tours refer to a particular practice by Canada's Saskatoon Police that is rarely documented but has resulted in at least five First Nations men freezing to death, including a 17-year-old boy, in the "wind-whipped prairie," according to the Washington Post .

A Starlight Tour is when police drive intoxicated Indigenous people out of town and leave them to walk home and sober up. According to CBC News , the practice was mostly the stuff of urban legend due to a lack of police reports from either side, but the activity underscores a long history of racism against Canada's Indigenous people who were dropped off many miles from home in freezing cold temperatures and left to try to make it home on foot.

The practice was first documented in 1976, Two Row Times reported, when two aboriginal men and a woman who was eight months pregnant were picked up by a Saskatoon police officer and dropped off outside of the city, left to make it home on their own.

The situation is described in the 2005 book, " Starlight Tour: The Last Lonely Night of Neil Stonechild. " According to the woman in the 1976 case, an officer approached her and her companions about drinking in public and told them to get into his cruiser. At first she thought they were going to jail. But that's not where they went.

The woman was the first person to report a Starlight Tour

According to the woman, the three friends fell into silence as the cruiser took them outside of town, not understanding what was happening. The cruiser came to a stop. The officer silently got out of the car, grabbed them each by the collar and pulled them out before getting back behind the wheel and wordlessly driving away. At first, she said they were relieved to have been released unharmed, but then, they realized how far they were from town. During the long walk home she resolved to report the incident, even though she thought no one would believe her. In the end, the woman was able to prove her story.

In October, 1976 the Saskatoon Police Chief posted a memo, which is published in "Starlight Tour: The Last Lonely Night of Neil Stonechild," for all of his staff to see. It read: "Instead of charging the people with having liquor in a place other then a dwelling, the officer (forced) the said persons into a Police vehicle and (drove) them to a remote area outside the City Limits and (left) said individuals to walk back to the City, particularly a female who was then eight months pregnant."

According to the memo, officer denied the accusations, but was found guilty. He was "reprimanded" and fined $200.

Remembering Neil Stonechild and exposing systemic racism in policing

Associate Professor of Gender, Religion and Critical Studies; Academic Director of the Community Research Unit, University of Regina

Disclosure statement

Michelle Stewart has received funding from a wide-range of agencies including but not limited to: Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council, Canadian Institutes of Health Research, National Science Foundation, and Saskatchewan Health Research Foundation.

University of Regina provides funding as a member of The Conversation CA-FR.

University of Regina provides funding as a member of The Conversation CA.

View all partners

On Nov. 29, 1990, the body of Neil Stonechild, a Saulteaux First Nations teen, was found frozen in a field on the outskirts of Saskatoon. It was -28C. He was just 17-years-old at the time of his death. He was found wearing only jeans and a light jacket and was missing one shoe.

Light jacket.

On Dec. 5, 1990, the Saskatoon Police Service closed the investigation into the death of Neil Stonechild. Despite visible injuries to the body of the Indigenous teenager, the file was closed. The investigation closed prior to receiving the Coroner’s Report, prior to receiving the toxicology report and prior to completing interviews with all witnesses.

In her book, Dying from Improvement , critical race scholar Sherene Razack discusses the Stonechild inquiry. She reports that the investigating officer said: “the kid went out, got drunk, went for a walk and froze to death.”

It would take over a decade and the freezing deaths of two more men and the near-death of another to crack the case wide open. Neil, the teenager, once dismissed as drunk and responsible for his own death, would become subject of a public inquiry that would lead to the firing of two police officers. His death would become synonymous with a racialized police practice called starlight tours.

Starlight tours describes a practice of police taking Indigenous people (said to have been picked up drunk or rowdy) and dropping them off at the edge of the city in the middle of the winter night . As Razak writes: “That there is a popular term [for this practice] is testimony to the fact that it happened more than once. The practice of drop-offs is a lethal one when the temperature is -28C and if the long walk back to town is undertaken without proper clothing and shoes.”

Remembering Neil

It’s November 2019, and I am talking to Neil’s brother, Chris Lindgren Astakeesic, about his brother’s death nearly 30 years ago. Chris recalls when his sister told him that Neil had died.

He was devastated. He had only been reunited with his younger brother and family in recent years after being in the foster care system and living outside Saskatchewan. Coming back into his family’s life, Chris made an immediate connection with Neil. Despite not being raised together, they shared a love of wrestling and created a solid bond.

Chris remembers Neil as many others did as a “fun-loving and very caring” person, adding that he “loved messing with him. He was a great kid and great brother. He loved life.”

Neil was wearing the letterman jacket that Chris gave him when he was found in the field. Stella, Neil’s mom, talked about the jacket during the inquiry into his death. The jacket had particular importance to Chris. Neil had treasured it and so Chris gave Neil the jacket before leaving for a trip to Ontario.

Given the sentimental importance of the jacket, Chris went to the police after the investigation concluded to request Neil’s belongings including the jacket. The Saskatoon Police told him they couldn’t find it. “I don’t even know if this has been told publicly,” says Chris. “But we couldn’t find any of his stuff.” The jacket and Neil’s other possessions were never returned. Chris tells me his mom, Stella, “was heartbroken.”

The inquiry

Chris speaks with a broken voice, recalling with vivid detail the time around Neil’s death and his experiences attending the inquiry as he drove back and forth to Saskatoon to attend as many dates as possible and be with his family.

I ask Chris what he thinks happened to Neil that night.

Chris mentions two police constables. “I think Hartwig and Senger had some fun, tried to scare him and it went to far,” he says. Chris recalls that Neil’s friend, Jason Roy, reported seeing Neil in the back of a police car that night. When Jason last saw Neil he was begging for help, screaming, “Help me, they are going to kill me.”

The findings of the inquiry established that police constables Larry Hartwig and Bradley Senger “took Stonechild into custody” and that the injuries and marks to his body “were likely caused by handcuffs.”

Hartwig and Senger argued their innocence and said they did not have contact with Stonechild that night. Evidence to the contrary was presented.

The evidence led Justice David H. Wright to conclude that Hartwig did recall the events that night (despite his assertions otherwise) and as such “ his assertions are deliberate deception designed to conceal his involvement .” The inquiry, through witness after witness’ testimony, offered a lesson in systemic racism in a settler state. But the recommendations did not address systemic racism and instead focused primarily on race relations.

Hartwig and Senger were dismissed from duty in November 2004 within a month of the report’s release. They appealed. Their appeals were rejected and the courts upheld the findings of the inquiry.

Stereotypes of victims hinder justice

The question of Neil’s personal belongings mirrors more recent stories in Saskatchewan. There are too many stories of other families that did not receive personal items from their loved ones. Often this is connected to a lack of investigation into sudden deaths.

After Nadine Machiskinic , a 29-year-old Indigenous mother of four died in Regina, the family reported her items were thrown away before a police investigation was even able to begin .

After 14-year-old Haven Dubois drowned in a shallow ravine, his family challenged the coroner’s report that had ruled his death an accident with marijuana as a contributing factor. His death had limited investigation.

The families of Haven and Nadine both argue their loved ones did not get a full investigation because of perceptions about them, as Indigenous people, on the prairies.

Like Neil’s family, these families fight for justice for years on end. They fight back against the ruling of accidental death. They call for inquiries and inquests. They fight back against assumptions made about the intoxication of the victim versus the real possibility of foul play.

Fifteen years later after the inquiry

The image of Neil Stonechild’s body lying in a frozen field still haunts the prairies.

The starlight tours continue to have ripple effects and impact relations between Indigenous peoples and police. The release of the 2004 Report of the Commission of Inquiry Into Matters Relating to the Death of Neil Stonechild called for reforms including more police accountability.

Of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission’s 94 Calls to Action, 18 deal with the criminal justice system . No. 39 calls upon the federal government to develop a national plan to collect and publish data on the criminal victimization of Aboriginal people, and No. 38 calls upon all levels of government to commit to eliminating the over-representation of Aboriginal youth in custody over the next decade. The TRC also placed emphasis on truth. We need to tell the truth about police practices and starlight tours in the prairies in Canada.

Concerns have been raised by the Federation of Sovereign Indigenous Nations (FSIN). “We have come a long way in 15 years but there is always room for improvement,” Dutch Lerat, the Vice Chief for the Federation of Sovereign Indigenous Nations, told APTN. “ We urge the Ministry of Justice to improve upon the public complaints process with emphasis on creating a civilian-led oversight authority .”

Saskatchewan is one of the last provinces to adopt independent civilian oversight despite ongoing, high-profile cases that raise concerns about how police work .

I spoke to Chris on the phone between anniversaries that no family should have to know: the freezing death of your loved one and the release of the findings of a public inquiry into their death.

“I am hoping [other families] can go back to this story for future reference and for future kids, so this doesn’t happen again.”

In honour of his memory: Neil Stonechild was a 17-year-old boy. His family loved him. Neil froze to death and some of the last people to see him alive were two police officers. Neil Stonechild died as a result of the starlight tours.

[ Deep knowledge, daily. Sign up for The Conversation’s newsletter .]

- Critical race

- Focus: Truth and Reconciliation in Canada

Faculty of Law - Academic Appointment Opportunities

Operations Manager

Senior Education Technologist

Audience Development Coordinator (fixed-term maternity cover)

Lecturer (Hindi-Urdu)

'Starlight Tours' fear felt by Indigenous people in Canada explored in TIFF short film

Director eva thomas’ redlights is now being made into a feature length film.

Social Sharing

Eva Thomas says directing, writing and producing Redlights was a deeply personal and ambitious project she found challenging and rewarding to bring to life.

The short film, being screened at the Toronto International Film Festival (TIFF) this week, is meant to portray "raw and unfiltered truth" of the fear experienced by Indigenous people when confronted by law enforcement, according to Thomas — who makes her directorial debut in it.

"A fear deeply rooted in a long and painful history of mistreatment, marginalization, and systemic injustice," she said.

The short is crafted around the action of Starlight Tours — where police take Indigenous people to remote areas in sub-zero temperatures, leaving them there to find their own way back.

Thomas is a Walpole Island First Nation member and splits her time between Wallaceburg, Ont., and Toronto.

"Shooting the film was a profound experience that allowed me to explore the emotions, histories, and realities faced by Indigenous communities in Canada," said Thomas.

Along with her involvement in numerous other projects, Thomas recently directed episodes for CBC's Still Standing, and wrote CTV's comedy series Shelved , CBC Gem's Zara , CTV/APTN series Acting Good and the upcoming Crave/APTN series Don't Even .

She calls the opportunity to screen Redlights at TIFF an "incredible honour," and says she's in the process of developing the short into a feature film.

Thomas spoke with CBC's Windsor Morning host Nav Nanwa.

Here is part of that conversation.

I've read that you describe the film Redlights as an Indigenous Thelma & Louise. So tell me a bit more about the characters in the film and what exactly they are going through.

I wanted to make an Indigenous Thelma & Louise about two Indigenous women on the run … young women who are just out at a bar on a Friday or Saturday night when they get separated and one of them gets taken into the police custody for what we know as a Starlight Tour.

Tell me a bit more about what a Starlight Tour is all about because I know that's that's the heavy emphasis of this film and pretty much the topic that it covers.

Starlight Tours are a term given to a practice that has been historically here in Canada, where police will take vulnerable Indigenous men and women often by themselves or drunk and then take them out to the middle of nowhere, often in subzero temperatures and leave them there to make their way back, find the way back.

They have historically been known to take place out west and Saskatchewan, but also been known to take place in northern Ontario.

I think the practice of Starlight Tours are happening less these days or not at all. I think a lot of work has been done with the police to sort of have some cultural sensitivity around that.

- Sask. man at centre of historic 'Starlight Tours' police misconduct case has died

Starlight Tours was just my mechanism to speak to the problems that sometimes happen when law enforcement meet Indigenous people in the policing of Black and brown bodies.

WATCH | Trailer for short film Redlights:

How did you tap into your own personal experience when it came to approaching this type of subject matter?

Luckily, I've saved myself a lot of trouble … My engagement with law enforcement has been minimal just because I keep myself out of trouble for all intents and purposes, but as an Indigenous person, I am aware of what's going on in my community.

I'm aware of other people who have had these sorts of experiences that might be tinged with a hint of racism.

And the Institute of policing is something that I think we deal with, maybe not specifically the Starlight Tours, but really just sometimes there being conflicts there at the relationship and sometimes the police not being seen as a place of safety for Indigenous people.

Dealing with such a heavy topic. What kind of mental toll did that take on you?

Yeah, It took a really long time to write it.

I thought at first maybe it would be like a domestic violence situation. They would find themselves in trouble with an eye toward that idea for a really long time.

But when I was writing it during COVID the world exploded after George Floyd and all these conversations and discussions around sort of policing.

- 15 must-see films to watch at TIFF 2023 — and after

And I thought, actually I have something to say about that too. So that's kind of why I sort of changed gears and sort of focused on this idea of a Starlight Tour, knowing about them historically happening to my people, my community being highly disturbed by them, and then also wanting to use that as a metaphor for the challenges we have sometimes with law enforcement.

I don't think all police are bad. I just think that sometimes the institution like power sometimes affects our relationship with law enforcement.

We mentioned earlier that the short film premiered on Friday at TIFF. What kind of feedback have you received since it was first screened?

I think what happens in the film, if you get a chance to see it, is there's a lot of tension. And what I was trying to convey was the sense of fear that we have of them [police].

And so I think people could really respond to that sense of tension or what I really want to see the film do was like, 'what would you do if you were in that situation?'

So I think a lot of people could find themselves pondering if that was me or if that was my friend, what would I do?

How do you hope a film like this one inspires other Indigenous directors and storytelling to be on the forefront?

What I'm finding is a lot of people are not aware of this [Starlight Tours] legacy in Canada. So there's this educational component of the film.

When I was writing it, there were times where I was kind of afraid to tell the story and I was like, maybe I shouldn't be telling this story, and how do I even have a lot of fear around telling the story?

I would say you have to be brave when you're a filmmaker to tell the truth.

Get the news you need without restrictions. Download our free CBC News App .

Q&A has been edited for length and clarity

Related Stories

- How a teenager from Halifax ended up directing her first short film

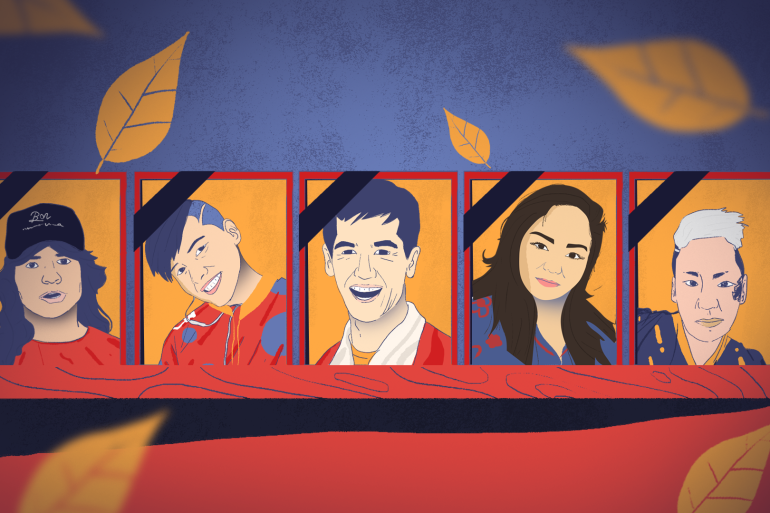

The Indigenous people killed by Canada’s police

The stories of Indigenous people who died in police encounters in Canada and the loved ones they left behind.

Despite making up just five percent of Canada’s population, 30 percent of the country’s prisoners are Indigenous. Across the prairie provinces of Manitoba, Saskatchewan and Alberta – regions that have higher populations of Indigenous people – that number rises to 54 percent.

According to a 2017 CTV News analysis, an Indigenous person in Canada is more than 10 times more likely to be shot and killed by a police officer than a white person. Between 2017 and 2020, 25 Indigenous people were shot and killed by the RCMP, Canada’s federal and national police service.

Keep reading

Is resource extraction killing indigenous women, chief allan adam on being beaten by police and indigenous rights, ‘it was sheer hatred’: the indigenous woman taunted as she died, know their names: black people killed by the police in the us external link this article will be opened in a new browser window.

The latest case came on February 27, when Julian Jones, a 28-year-old Tla-o-qui-aht man, was shot and killed in British Columbia after Tofino police responded to a call for help from the Opitsaht reserve, which is accessible only by boat.

It was the second police killing of a Tla-o-qui-aht First Nation member in less than a year, following the death of Chantel Moore in June 2020.

Here are the stories of some of the Indigenous men and women who have been killed in encounters with Canadian police.

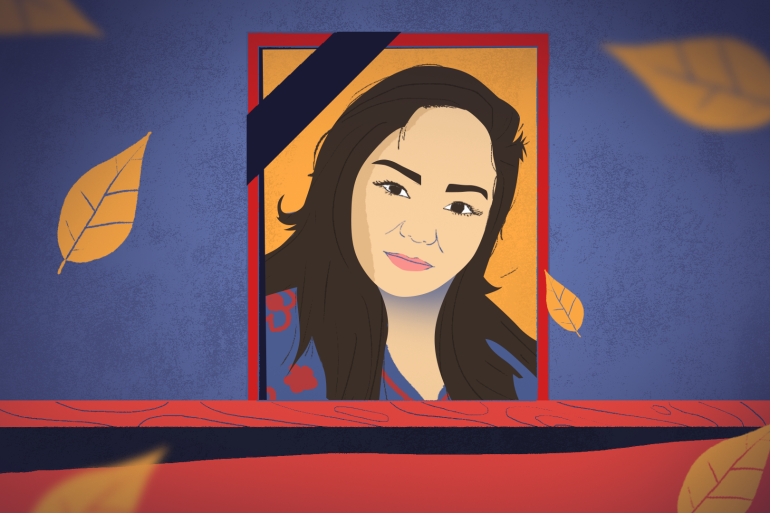

‘I want to get angel wings’ Chantel Moore, 26 – killed June 4, 2020

In the early hours of the morning on June 4, 2020, police in the New Brunswick city of Edmundston reportedly responded to a call from Chantel Moore’s boyfriend requesting a wellness check. Her boyfriend, who lived more than 1,000km (600 miles) away in Toronto, reportedly believed that Chantel was being harassed. The 26-year-old Tla-o-qui-aht First Nation member from British Columbia had recently moved to New Brunswick to be closer to her six-year-old daughter, who lived with Chantel’s mother.

A few minutes later, Chantel – who her family described as “a good mom”, someone who “made friends wherever she went” and “loved to make people laugh” – was dead.

According to the police, Chantel had walked out of her apartment onto a balcony with a knife and had threatened the officer, who then shot her.

“I don’t understand how someone dies during a wellness check,” Indigenous Services Minister Marc Miller said at a news conference following Chantel’s death.

After Chantel’s body was returned to British Columbia, her maternal grandmother, Grace Frank, and her mother, Martha Martin, went to view it.

“Her face was bruised, her right eye sunk in. She had seven gunshot wounds on her body and her left leg wasn’t attached below the kneecap,” Grace recalled tearfully, adding that the police had not offered any explanation for the condition of her body.

The family wanted to protect Chantel’s daughter, Gracie – named after her great-grandmother – from learning how her mother died, but the six-year-old accidentally saw a news report about it on TV. Her great-grandmother says it left her devastated: “Gracie is so sad. She says, ‘I want to get angel wings. I want to go see my mom.’ And then she’s scared and cries, ‘I don’t wanna be shot like that, I don’t wanna die like that.'”

Grace remembered how Chantel would go out of her way to give her daughter the best Christmases and birthdays she could, adding: “Chantel was such a good mommy.”

“[She] was the kindest, [most] caring, loving, supportive, bubbly person. She never had hate for anyone. People loved her.”

When asked about the condition of Chantel’s body, Mychèle Poitras, communications director for the City of Edmundston, said: “No comments can be made since the file is with the Provincial Prosecutor’s Office.”

The name of the officer who shot Chantel has not been released, but eight investigators with Quebec’s independent police watchdog group (New Brunswick does not have its own) have completed an investigation into her death. The Bureau des enquetes independantes forwarded its report to New Brunswick’s Public Prosecution Service and to the case coroner in December. The prosecutions office has said it will review the report and determine whether to charge the officer.

The Tla-o-qui-aht First Nation is demanding that the officer be charged with murder and that body cameras be mandatory for all police officers working with the public. It has also requested a full national inquiry into the root causes of police brutality against Indigenous people.

“This killing was completely senseless,” the Nation said in a press release. “At the Missing and Murdered Indigenous Women and Girls Inquiry, RCMP Commissioner Brenda Lucki committed to do better by First Nations. She said, ‘I’m sorry that for too many of you, the RCMP was not the police service that it needed to be during this terrible time in your life. It is very clear to me that the RCMP could have done better and I promise to you we will do better.’ We are still waiting for ‘better’ and Chantel certainly deserved ‘better.’”

In mid-November, less than six months after Chantel’s death, her 23-year-old brother Mike Martin took his own life while being held in a correctional centre in British Columbia. “I’m trying to be OK but I’m sad,” wrote Grace in a social media post in December. “I’m hurting. I’m angry. I’m full of rage. I’m full of disgust. I think about my granddaughter and my grandson – they should both be alive. It’s so unfair they’re gone … I will not give up until justice is served. My heart is aching.”

The ‘starlight tours’ Neil Stonechild, 17 – killed November 1990

On the golden, wheat-covered prairies of Saskatchewan, a deadly phenomenon known as the “starlight tours” has been threatening Indigenous people for decades.

No one here is certain where or when the term originated, but Indigenous residents know exactly what it stands for: police taking Indigenous people – often said to have been picked up while intoxicated – and dropping them off at the edge of the city of Saskatoon at night, where temperatures regularly drop to as low as -28C (-20F) during winter.

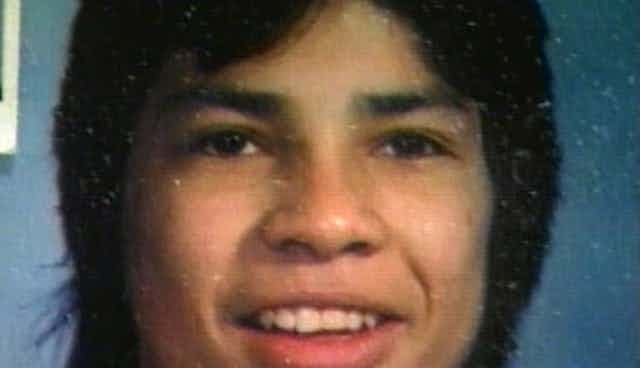

In November 1990, a 17-year-old Saulteaux First Nations boy was found frozen to death in a field on the outskirts of Saskatoon. Neil Stonechild was face down in the snow, wearing one shoe, and had cut marks on his face and arms. He was found by construction workers on November 29 – five days after he was last seen.

An autopsy indicated that he had died of hypothermia. But his devastated family suspected foul play.

A police investigation into his death was closed after just three days. Former Saskatoon police Sergeant Keith Jarvis, who conducted the investigation, explained in his report: “It is felt that unless something concrete by way of evidence to the contrary is obtained, the deceased died from exposure and froze to death.”

At the time of his death, Neil was living between a group home – accommodation that houses multiple children and young people in the foster care system – in the west end of Saskatoon and his mother’s house.

According to his older brother, Dean Lindgren, who is now 54, Neil was a “good kid” who dabbled in “petty crime” but was not involved in violent crime or gangs.

The night Neil died he was wearing his brother’s high school letterman jacket. It was, Dean remembered, one of his most prized possessions. “For a long time he kept asking me, ‘Bro, can I have your jacket?’” said Dean, who finally relented and gave it to his brother, who wore it “proudly” around Saskatoon.

Neil was an athlete, who excelled at wrestling, Dean recalled.

The two brothers had a strong bond, even though they had only known each other for two-and-a-half years when Neil died. Dean had been taken from his family as part of the “60s scoop”, a practice enacted by provincial and federal Canadian governments from the 1960s to the 1980s in which Indigenous children were taken from their families and adopted by white families across Canada and the US.

After finishing high school, Dean travelled from his adoptive home in Minnesota in the US to find his biological family in Saskatoon. He immediately bonded with his younger brother and said that the week before he died, the two brothers had planned to travel to the province of Ontario to pick up a car Dean had bought and drive it back to Saskatoon together.

“He wanted to come so bad,” Dean said of his brother. But in the end, Dean went alone. “I kick myself every time I talk about this,” he said.

Driving back to Saskatoon, Dean hit black ice and destroyed his new car. He borrowed a stranger’s phone to call home. The US Army veteran breaks down in tears as he describes what happened next.

“I called my cousin Andrea. I was frantic about my car. But she asked me, ‘Are you sitting down?… Dean, your brother was killed.’”

His world momentarily stopped. Then the words hit him – hard. He took a bus back to Saskatoon.

Dean remembers hearing that Neil was with his 16-year-old friend Jason Roy the night he went missing. But, for 10 years, Jason did not talk about what happened that night. He later explained in a phone call from his home in Saskatoon that he had been traumatised and scared of potential repercussions for speaking out.

Then, on January 19, 2000, Lloyd Dustyhorn, a 53-year-old First Nations man was found frozen to death in Saskatoon. The day before he had been taken into custody by police for public intoxication – in May 2001, following an inquest, a jury decided that his death had been caused by hypothermia.

Later that month, Darryl Night, a Cree man from Saskatoon, told police that two officers had dropped him off several miles outside of Saskatoon in freezing temperatures. Darryl had been having a drunken argument with his uncle and said the officers picked him up outside his uncle’s apartment before dawn on January 28. He was wearing only a T-shirt and running shoes when they left him in a remote rural area outside the city. He managed to walk several miles to a power station where a watchman let him call a taxi.

The next day, the shirtless body of Rodney Naistus, a 25-year-old Indigenous man, was found near where Darryl said the police officers had dropped him off. A few days later, on February 3, 2000, the body of another Indigenous man, 30-year-old Lawrence Kim Wegner, who had last been seen three days earlier, was found wearing only a T-shirt, socks and jeans. Both men appeared to have frozen to death, possibly dying within hours of being released from police custody, according to police investigations and public inquests.

These cases prompted the Province of Saskatchewan to hold an inquiry into the alleged “starlight tours” and to re-examine Neil’s death.

Jason testified at the inquiry, telling it about the last time he had seen his friend alive on that bitterly cold November night in 1990. He and Neil had been walking in the city’s west end after drinking at an apartment building in the area, he said. The two briefly separated, Jason recalled, and the next time he saw Neil he was in the backseat of a police cruiser, with a bloodied face, screaming for help and telling Jason: “They’re going to kill me.”

The inquiry found that Neil was in the custody of police Constables Larry Hartwig and Bradley Senger and that the injuries and marks to his body “were likely caused by handcuffs.” The officers denied having been in contact with Neil the night he died, but the evidence contradicted their claim and the two were dismissed from duty in November 2004. A court upheld the findings of the inquiry when the two officers appealed against it.

Despite this, no Saskatoon police officer has been tried for Neil’s death or those of any of the other Indigenous people who froze to death.

Today, Dean says he harbours hatred for the officers he believes took the life of his brother. “I will never forgive Hartwig and Senger, never,” he said, angrily.

When George Floyd was killed by US police in Minneapolis, Dean said it stirred up memories. “I understand exactly what the family (George Floyd’s) is going through,” he said. “When I saw the cops killing George Floyd on the video, I had instant rage. Down here it’s not safe for the Blacks and up in Canada it’s bad for the Natives.”

Back in Saskatoon, Jason is working to overcome the trauma of the last time he saw his friend. He wants the police to implement the recommendations of the inquiry into his friend’s death, which included cultural and sensitivity training to equip police to deal with high-stress situations involving Indigenous people who are often dealing with trauma as a result of generations of abuse, neglect and discrimination.

“The police have only found different ways to abuse our people. My people are still being abused,” he said. “But I’m not scared of them – there is no way I was going to let them win.”

‘His life was only worth 20 minutes of their time’ Rodney Levi, 48 – killed June 12, 2020

Eight days after the death of Chantel Moore, 48-year-old Rodney Levi, a Metepenagiag Mi’kmaq man, was killed in the same province.

Late in the afternoon of June 12, the Sunny Corner RCMP Detachment reportedly received a call about a man acting strangely at a home near the Metepenagiag First Nation.

According to a report by the Bureau des enquêtes indépendantes du Québec when police arrived at the scene, Rodney was armed with knives and charged at one of the two officers. A taser was deployed three times but failed to subdue him. One of the officers shot Rodney twice in the chest. He was pronounced dead at the hospital.

Investigators from the Bureau interviewed witnesses, one of whom described Rodney as “being severely depressed” in the days before his death and as having talked about “suicide by RCMP”.

Rodney’s brother-in-law, Norman Ward, told Al Jazeera the father-of three had battled “demons” in the form of drug addiction but added that he did not believe he posed a threat to anyone.

“With Rodney gone, a big piece is missing as he always brought everyone together,” he said. “Things will never be the same with him gone. He didn’t die of natural causes. His life was stolen, not just from him but from everyone who loved him.”

Norman described him as having a way with people, especially children. “All his nieces and nephews looked up to him. He went out of his way to play with them. He was like a big kid.”

According to Lisa Levi, Rodney’s sister, he had been attending a BBQ at the home of his pastor from the Boom Road Pentecostal Church – a church he had been attending on and off for approximately three years – when he was shot by police on the back deck.

“From what I understand, Rodney was invited by Pastor Brodie [MacLeod] to have supper with the family. They all knew Rodney and loved him. Some time during the time he was there Rodney became paranoid and had put a knife in his hoodie pocket for protection. Someone (we’re not sure who) called the police,” Lisa explained.

Pastor Brodie MacLeod released a statement after Rodney’s death to dispel the rumours that he had been an “unwanted guest”. “Rodney Levi was a welcomed guest at our home and he attended our residence when he shared a meal with my family and I on Friday evening,” he wrote.

Lisa said Rodney had been trying for several months to get psychiatric help but had been denied admission for treatment at the local hospital.

The police spoke to Rodney for 20 minutes before he was shot. “That officer showed up, knew Rodney was Indigenous and decided that Rodney was not worth the effort to talk to. Because the very next week, a white guy at the Miramichi hospital held a nurse at knifepoint. They gave that man a hostage negotiator and hours to talk him down. Our Rodney was given 20 minutes! That’s the hardest part – knowing Rodney’s life was only worth 20 minutes of their time,” said Lisa.

“I wonder, did he suffer and was he scared?” she said, crying.

Lisa says she now experiences anxiety when driving outside of her community. “A week after Rodney was killed, I was driving down the highway and a cop pulled out behind me. I was sweating, started to get anxious. Even though my vehicle was insured and registered, I didn’t feel safe because I’m Indigenous.”

Her children, aged 7, 13 and 14, are also afraid, she adds. “They know how their uncle was. He was so nice, so gentle. Never violent. It makes me cry. I want to protect my kids to not have to go through this, but racism is still here.”

Norman is convinced Rodney would still be alive if he were white. “The whole justice system is against us,” he said. “There’s so much racism in this area. They (police) beat up our people. All they want to do is arrest us and be aggressive to us. There is still so much tension here since Rodney died.”

The RCMP is not currently commenting on Rodney’s death as the case is being reviewed by the New Brunswick Prosecution Service.

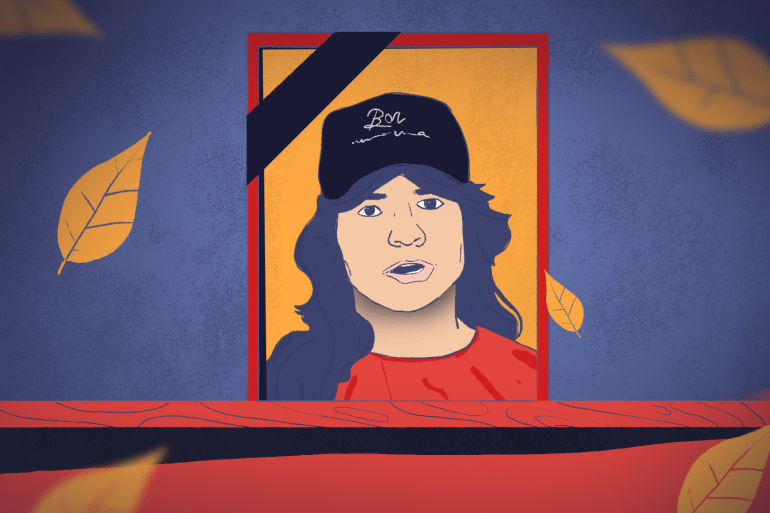

‘She was a kid’ Eishia Hudson, 16 – killed April 8, 2020

On April 8, 2020, police in Winnipeg, Manitoba, shot and killed Eishia Hudson, a 16-year-old First Nations girl. Police say they received a report that a group of teenagers had robbed a liquor store in the Sage Creek area. Within minutes, several police vehicles were chasing the stolen SUV the teenagers were in.

The pursuit came to an end when the police cars blocked in the SUV and an officer shot Eishia, who had been driving the stolen SUV. She was transported to hospital but succumbed to her injuries.

The night Eishia was killed, her father, William Hudson, got a call from one of his other daughters expressing concern about Eishia. He went out looking for her.

“I went around to every hospital and called all the police stations,” he said. “No one told me anything.”

A little later, he heard the news from one of his other daughters.

“It’s tough. It’s unbelievable. It’s still hard for me to believe,” he said.

Just 12 hours later, one of his closest friends, 36-year-old Indigenous father-of-three Jason Collins, had been shot and killed by Winnipeg police officers responding to a domestic violence call.

Of his daughter, William said, “[she had a smile] so bright it didn’t matter how you were feeling or what you were going through, she brought brightness to anyone she was around. She had a positive attitude towards everything”.

He says Eishia was not a troublemaker and describes her as a happy person who loved to play sports and make people laugh.

“I enjoyed laughing with her, listening to her sing, watching her play sports. Every moment I had with Eishia is my favourite memory of her.”

He believes racism played a role in her death.

“It’s hard to be Indigenous in Canada. Where I grew up here in the north end, it’s lower-income, there’s gangs. We grew up with racist cops and a racist child welfare system,” William explained.

The family held a funeral for Eishia in April amid COVID-19 lockdowns. William says hundreds of people turned up at the funeral home to pay their respects before she was cremated but only 10 could be ushered through at a time.

The family says it is waiting to get answers from the police about why other tactics were not used to apprehend her before burying her remains.

William says Winnipeg’s Indigenous community has been a great source of support for him. He has organised multiple rallies and vigils for Eishia, which he says helps to make him feel as though he is not carrying the load of her loss alone. But, he says, neither the police nor the city or provincial authorities have reached out to him.

His younger children are afraid to leave the house since Eishia died, he explained, adding that whenever he takes his five-year-old daughter to the local grocery store, she grabs his leg if she sees a police officer on patrol.

“For us, when we leave the house, we know we’re leaving as an Indigenous person. To be on guard. I hope one day it will change.”

Following an investigation into Eisha’s death, Manitoba’s Independent Investigation Unit (IIU) concluded that there was no evidence the officer had been unjustified in using lethal force. William dismissed the report as “biased”.

“My daughter, her life mattered. She was a kid and what the cops did, that was wrong,” William said, adding: “It has to come to an end.”

‘My sunshine girl’ Josephine Pelletier, 33 – killed May 17, 2018

Josephine Pelletier was shot dead by police in Calgary, Alberta, on May 17, 2018. The 33-year-old Cree woman was with her 18 year-old-son Elijah, and according to police, was barricaded in the basement of a residence that was not her home.

“I had a strange feeling about Josephine and her boy [around the time she was killed],” Josephine’s mother, Donna Pelletier, explained during a phone call from her home in Saskatchewan.

Family friends called to tell her the news after learning of Josephine’s death on social media.

“I said, ‘If this is about Josephine, I don’t want to hear it.’ Everything went blank after that,” she recalled.

Josephine had attended one of Canada’s last residential schools – which closed in 1996. In an interview before her death, she had described to this writer the relentless verbal, physical and sexual abuse she had endured there.

Canada’s federal residential school system, which started in 1883, forcibly removed Indigenous children from their families, communities and cultures.

After leaving school, Josephine spent much of her life in jail. But, in 2015, she had reached out to the Aboriginal Peoples Television Network (APTN) from a half-way house in Calgary to share her story and plead for help. “I need help,” she told the channel. “How to learn to unlock my mind from being an angry person. From being locked up all the time and fighting. I want to be in control of my mind, feelings, my heart and my body. I want to be a mom. I want to give my son something to look at and be proud of.”

Josephine had been on the run from a Calgary half-way house for a couple of days when the upstairs occupants of the residence where she was killed called the police to report a home invasion. Police arrived with a K9 unit and a tactical team. According to news reports, police officers heard sounds of distress from inside and two officers fired live rounds at Josephine, who was unarmed. She died on the scene.

Police also shot Elijah with rubber bullets, rendering him unconscious. To this day, Donna says, he has no recollection of his mother’s death.

About a week and a half after Josephine was killed, Donna had raised enough money through an online appeal to be able to bring her daughter’s body home to Saskatchewan.

“They didn’t wipe her up. There was still blood on her body. There was a bullet by her ear, one on the back of her head, one on her arm – she must have put her arms up. I saw three bullets, but then I couldn’t look any more,” she explained.

Josephine was buried in the Muskowekwan First Nation that June. Elijah could not attend the funeral because he was in jail facing various charges related to the incident on the day of his mother’s death. A court subsequently ordered that he be admitted to a psychiatric hospital, where he remains today.

“They found him hanging at the Edmonton Remand Center,” said Donna of her now 20-year-old grandson. “It was the third time he tried to commit suicide.”

She described Elijah as smart, quiet, but quick-tempered, like his mother. “But now, they keep him drugged up, he doesn’t sound like himself.”

Donna says she has been left with unanswered questions. “They (police) won’t give me answers. They keep giving me the run-around.”

When she visits Josephine’s grave, the pain is still fresh. Although her daughter lived a troubled life, Donna says she now likes to imagine that her “sunshine girl” is at peace with the angels.

Josephine’s death is currently under investigation by the Alberta Serious Incident Response Team (ASIRT). The ASIRT told Al Jazeera by email that it is unsure when a decision will be made regarding the actions of police in Josephine’s death.

IMAGES