The Art of Narrative

Learn to write.

A Complete Guide to The Hero’s Journey (or The Monomyth)

Learn how to use the 12 steps of the Hero’s Journey to structure plot, develop characters, and write riveting stories that will keep readers engaged!

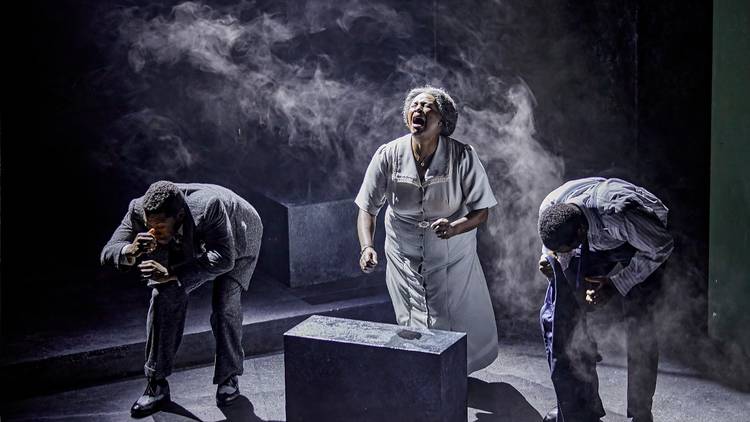

Before I start this post I would like to acknowledged the tragedy that occurred in my country this past month. George Floyd, an innocent man, was murdered by a police officer while three other officers witnessed that murder and remained silent.

To remain silent, in the face of injustice, violen ce, and murder is to be complicit . I acknowledge that as a white man I have benefited from a centuries old system of privilege and abuse against black people, women, American Indians, immigrants, and many, many more.

This systemic abuse is what lead to the murder of George Floyd, Breonna Taylor, Ahmaud Arbery, Sandra Bland, Eric Garner, Treyvon Martin, Philando Castile, Freddie Gray, Walter Scott, Tamir Rice and many more. Too many.

Whether I like it or not I’ve been complicit in this injustice. We can’t afford to be silent anymore. If you’re disturbed by the violence we’ve wit nessed over, and over again please vote this November, hold your local governments accountable, peacefully protest, and listen. Hopefully, together we can bring positive change. And, together, we can heal .

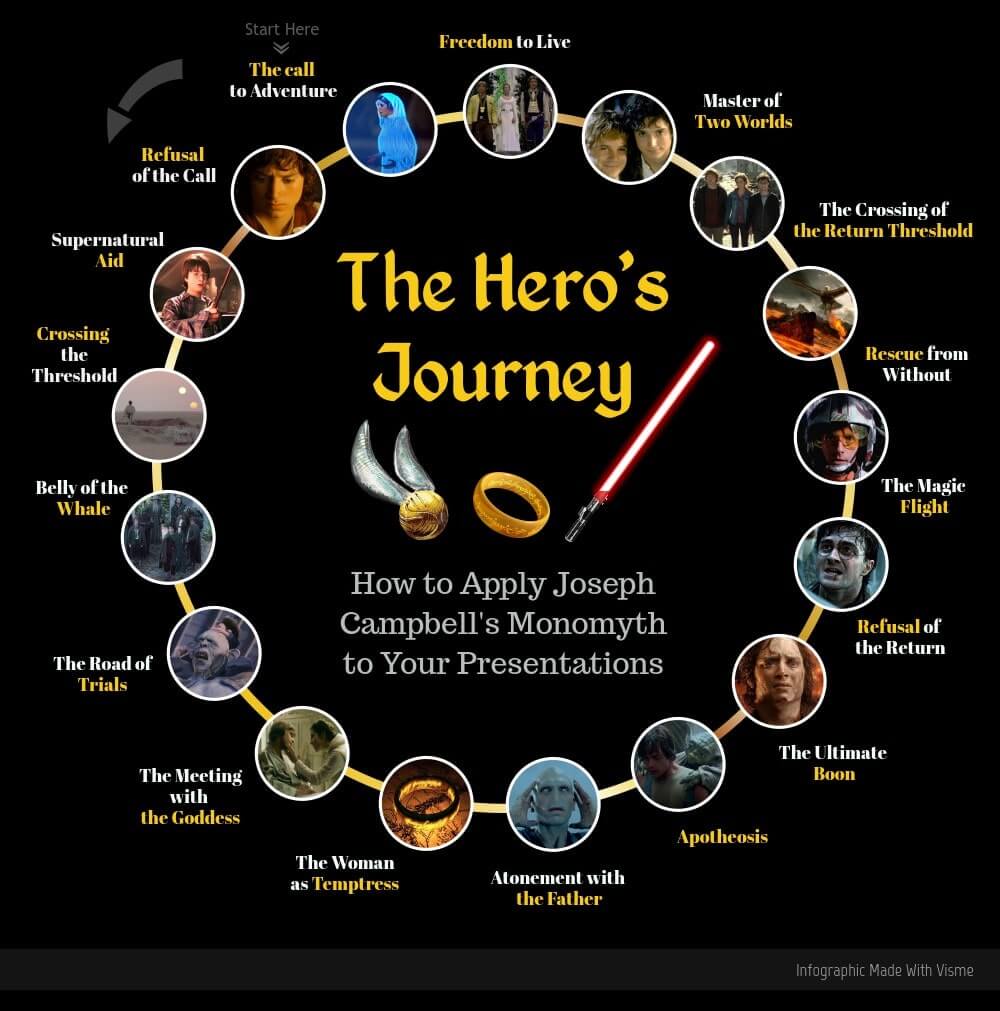

In this post, we’ll go over the stages of Joseph Campbell’s Hero’s Journey, also known as the Monomyth. We’ll talk about how to use it to structure your story. You’ll also find some guided questions for each section of the Hero’s Journey. These questions are designed to help guide your thinking during the writing process. Finally, we’ll go through an example of the Hero’s Journey from 1997’s Men In Black.

Down at the bottom, we’ll go over reasons you shouldn’t rely on the Monomyth. And we’ll talk about a few alternatives for you to consider if the Hero’s Journey isn’t right for your story.

But, before we do all that let’s answer the obvious question-

What is the Hero’s Journey?

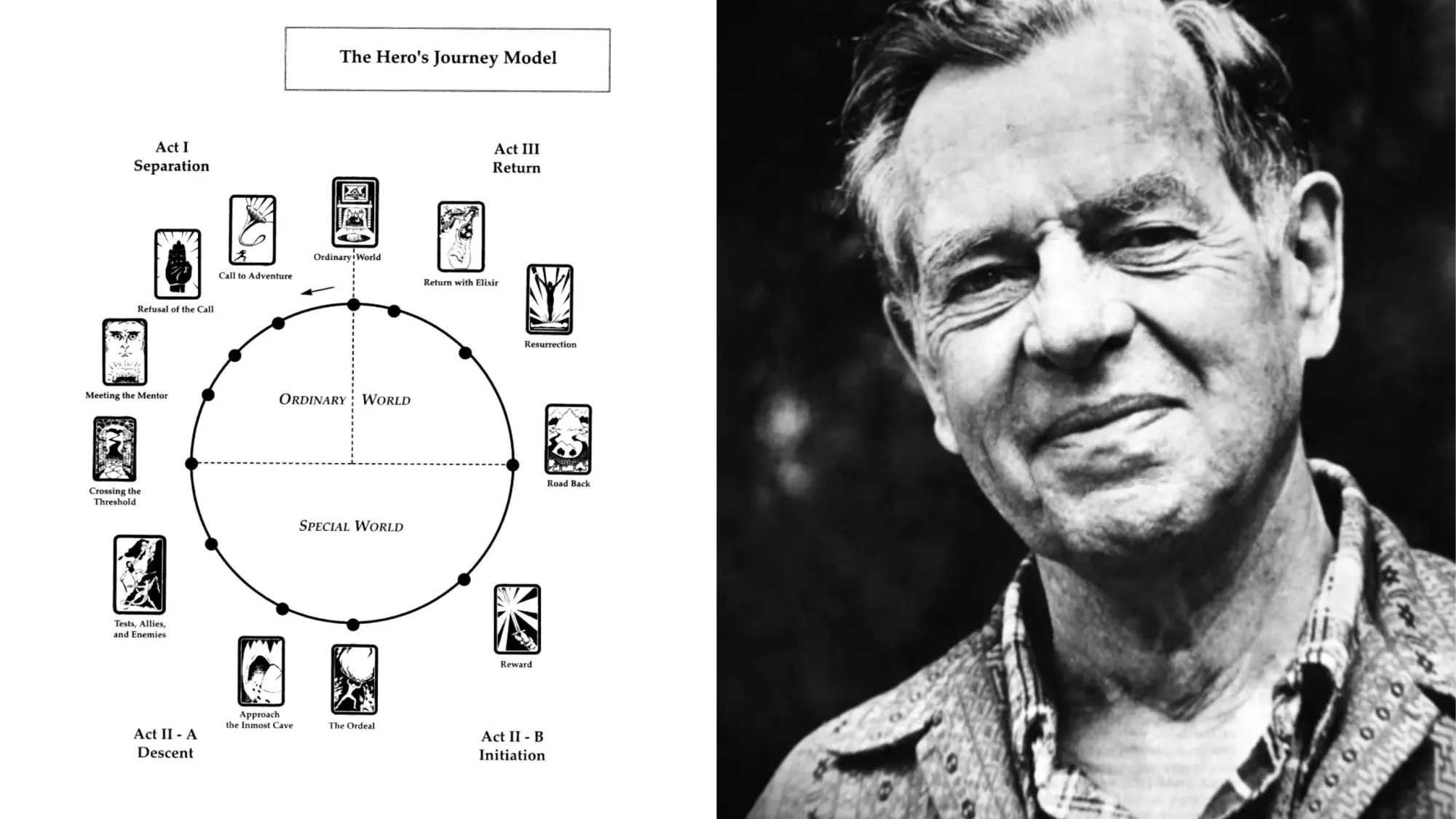

The Hero’s Journey was first described by Joseph Campbell. Campbell was an American professor of literature at Sarah Lawrence College. He wrote about the Hero’s Journey in his book The Hero with a Thousand Faces . More than a guide, this book was a study on the fundamental structure of myths throughout history.

Through his study, Campbell identified seventeen stages that make up what he called the Monomyth or Hero’s Journey. We’ll go over these stages in the next section. Here’s how Campbell describes the Monomyth in his book:

“A hero ventures forth from the world of common day into a region of supernatural wonder: fabulous forces are there encountered and a decisive victory is won: the hero comes back from this mysterious adventure with the power to bestow boons on his fellow man.”

Something important to note is that the Monomyth was not conceived as a tool for writers to develop a plot. Rather, Campbell identified it as a narrative pattern that was common in mythology.

George Lucas used Campbell’s Monomyth to structure his original Star Wars film. Thanks to Star Wars ’ success, filmmakers have adopted the Hero’s Journey as a common plot structure in movies.

We see it in films like The Matrix , Spider-man , The Lion King , and many more. But, keep in mind, this is not the only way to structure a story. We’ll talk about some alternatives at the end of this post.

With that out of the way, let’s go over the twelve stages of the Hero’s Journey, or Monomyth. We’ll use the original Men In Black film as an example (because why not?). And, we’ll look at some questions to help guide your thinking, as a writer, at each stage.

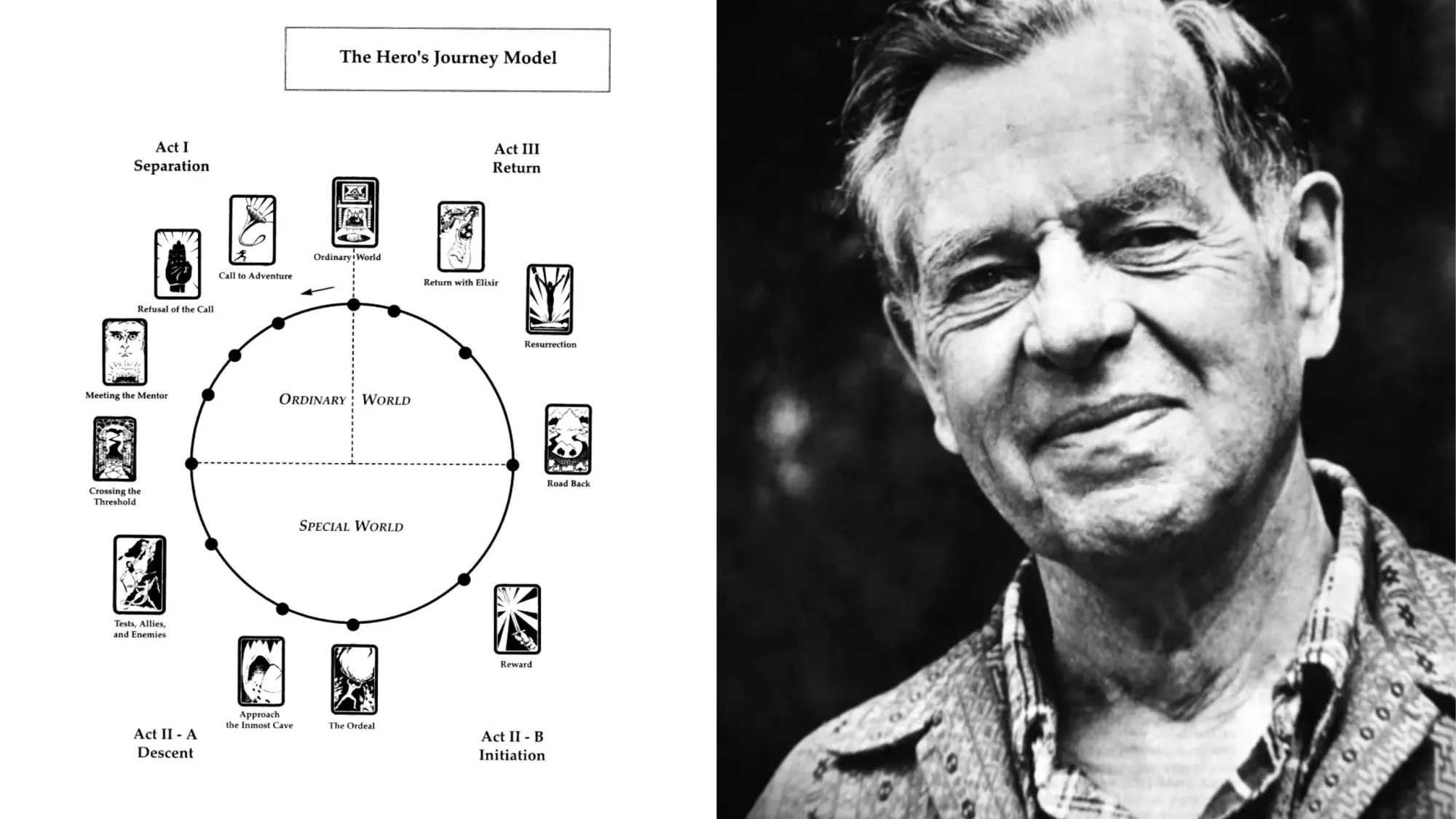

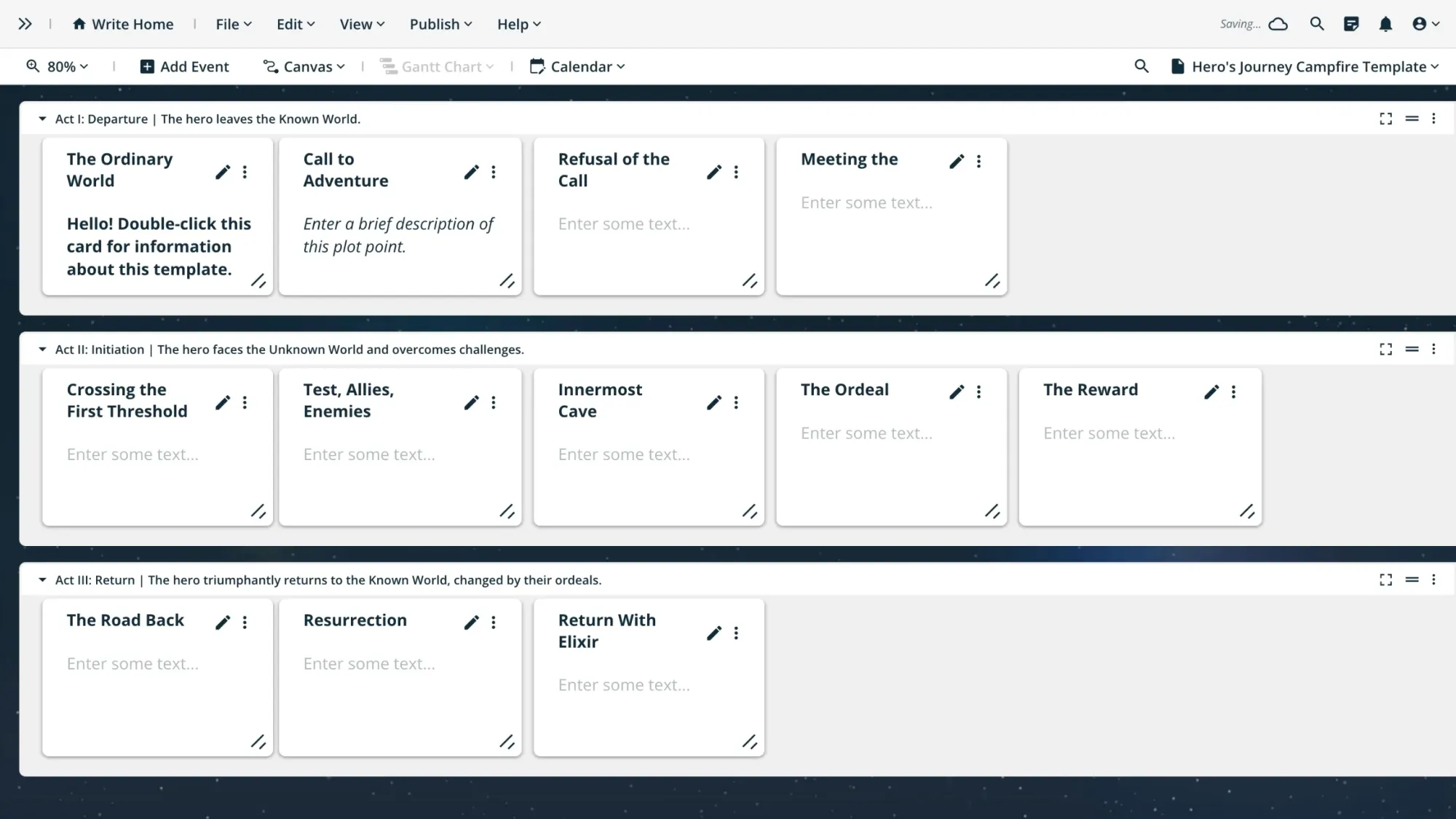

Quick note – The original Hero’s Journey is seventeen stages. But, Christopher Vogler, an executive working for Disney, condensed Campbell’s work. Vogler’s version has twelve stages, and it’s the version we’re talking about today. Vogler wrote a guide to use the Monomyth and I’ll link to it at the bottom.)

The 12 Stages of The Hero’s Journey

The ordinary world .

This is where the hero’s story begins. We meet our hero in a down-to-earth, or humble setting. We establish the hero as an ordinary citizen in this world, not necessarily “special” in any way.

Think exposition .

We get to know our hero at this stage of the story. We learn about the hero’s life, struggles, inner or outer demons. This an opportunity for readers to identify with the hero. A good idea since the story will be told from the hero’s perspective.

Read more about perspective and POV here.

In Men In Black, we meet our hero, James, who will become Agent J, chasing someone down the streets of a large city. The story reveals some important details through the action of the plo t. Let’s go over these details and how they’re shown through action.

Agent J’s job: He’s a cop. We know this because he’s chasing a criminal. He waves a badge and yells, “NYPD! Stop!”

The setting: The line “NYPD!” tells us that J is a New York City cop. The chase sequence also culminates on the roof of the Guggenheim Museum. Another clue to the setting.

J’s Personality: J is a dedicated cop. We know this because of his relentless pursuit of the suspect he’s chasing. J is also brave. He jumps off a bridge onto a moving bus. He also chases a man after witnessing him climb vertically, several stories, up a wall. This is an inhuman feat that would have most people noping out of there. J continues his pursuit, though.

Guided Questions

- What is your story’s ordinary world setting?

- How is this ordinary world different from the special world that your hero will enter later in the story?

- What action in this story will reveal the setting?

- Describe your hero and their personality.

- What action in the story will reveal details about your hero?

The Call of Adventure

The Call of Adventure is an event in the story that forces the hero to take action. The hero will move out of their comfort zone, aka the ordinary world. Does this sound familiar? It should, because, in practice, The Call of Adventure is an Inciting Event.

Read more about Inciting Events here.

The Call of Adventure can take many forms. It can mean a literal call like one character asking another to go with them on a journey or to help solve a problem. It can also be an event in the story that forces the character to act.

The Call of Adventure can include things like the arrival of a new character, a violent act of nature, or a traumatizing event. The Call can also be a series of events like what we see in our example from Men In Black.

The first Call of Adventure comes from the alien that Agent J chases to the roof of the Guggenheim. Before leaping from the roof, the alien says to J, “Your world’s going to end.” This pique’s the hero’s interest and hints at future conflict.

The second Call of Adventure comes after Agent K shows up to question J about the alien. K wipes J’s memory after the interaction, but he gives J a card with an address and a time. At this point, J has no idea what’s happened. All he knows is that K has asked him to show up at a specific place the next morning.

The final and most important Call comes after K has revealed the truth to J while the two sit on a park bench together. Agent K tells J that aliens exist. K reveals that there is a secret organization that controls alien activity on Earth. And the Call- Agent K wants J to come to work for this organization.

- What event (or events) happen to incite your character to act?

- How are these events disruptive to your character’s life?

- What aspects of your story’s special world will be revealed and how? (think action)

- What other characters will you introduce as part of this special world?

Refusal of the Call

This is an important stage in the Monomyth. It communicates with the audience the risks that come with Call to Adventure. Every Hero’s Journey should include risks to the main characters and a conflict. This is the stage where your hero contemplates those risks. They will be tempted to remain in the safety of the ordinary world.

In Men in Black, the Refusal of the Call is subtle. It consists of a single scene. Agent K offers J membership to the Men In Black. With that comes a life of secret knowledge and adventure. But, J will sever all ties to his former life. No one anywhere will ever know that J existed. Agent K tells J that he has until sunrise to make his decision.

J does not immediately say, “I’m in,” or “When’s our first mission.” Instead, he sits on the park bench all night contemplating his decision. In this scene, the audience understands that this is not an easy choice for him. Again, this is an excellent use of action to demonstrate a plot point.

It’s also important to note that J only asks K one question before he makes his decision, “is it worth it?” K responds that it is, but only, “if you’re strong enough.” This line of dialogue becomes one of two dramatic questions in the movie. Is J strong enough to be a man in black?

- What will your character have to sacrifice to answer the call of adventure?

- What fears does your character have about leaving the ordinary world?

- What risks or dangers await them in the special world?

Meeting the Mentor

At this point in the story, the hero is seeking wisdom after initially refusing the call of adventure. The mentor fulfills this need for your hero.

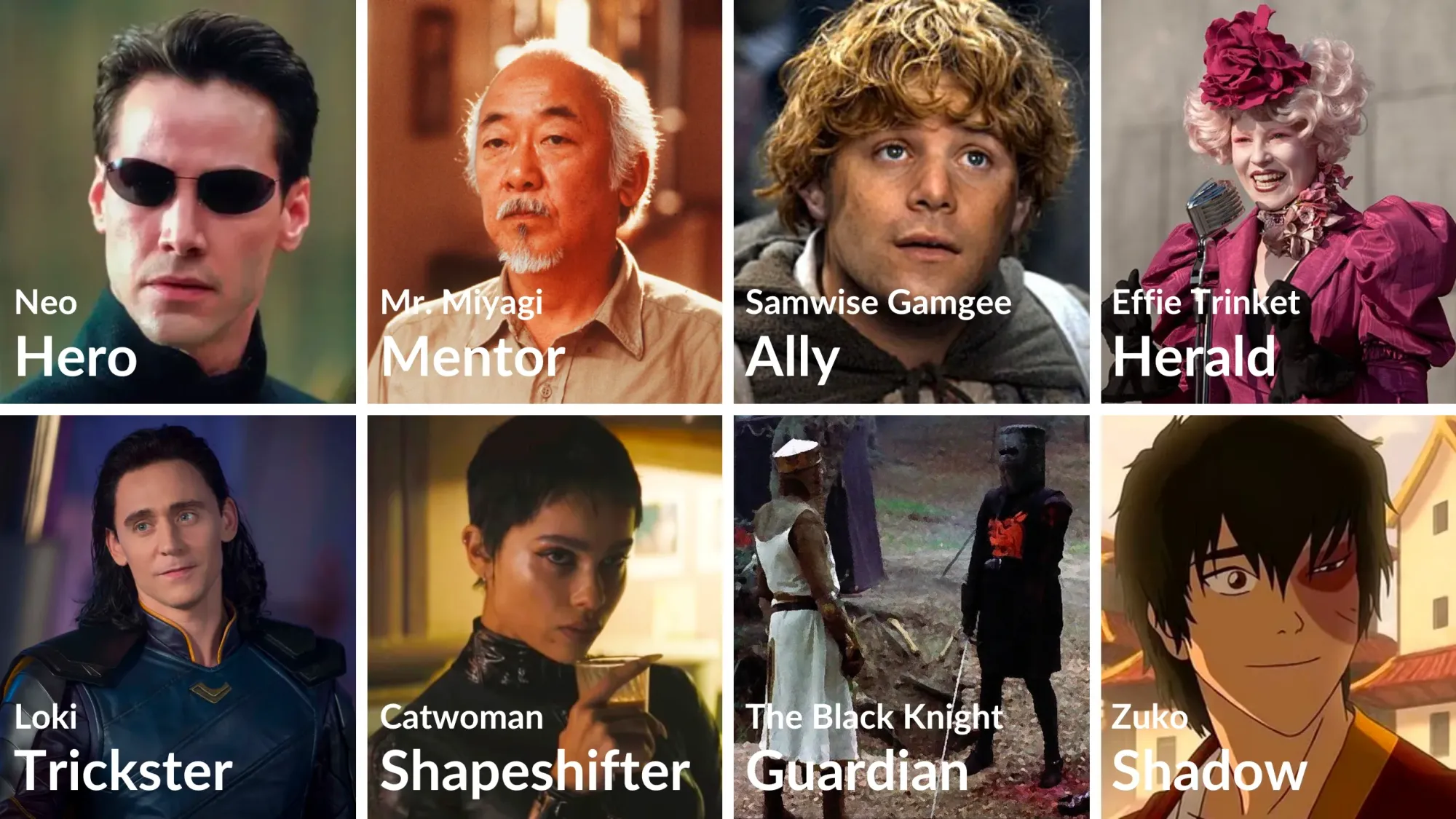

The mentor is usually a character who has been to the special world and knows how to navigate it. Mentor’s provides your hero with tools and resources to aid them in their journey. It’s important to note that the mentor doesn’t always have to be a character. The mentor could be a guide, map, or sacred texts.

If you’ve seen Men In Black then you can guess who acts as J’s mentor. Agent K, who recruited J, steps into the mentor role once J accepts the call to adventure.

Agent K gives J a tour of the MIB headquarters. He introduces him to key characters and explains to him how the special world of the MIB works. Agent K also gives J his signature weapon, the Noisy Cricket.

- Who is your hero’s mentor?

- How will your character find and encounter with their mentor?

- What tools and resources will your mentor provide?

- Why/how does your mentor know the special world?

Crossing the Threshold

This is the point where your hero finally crosses over from the ordinary world into the special one. At this point, there is no turning back for your hero.

Your hero may not cross into the special world on their own. Or, they may need a dramatic event that forces them to act.

At this point, you’ll want to establish the dramatic question of your story. This is the question will your reader wants to answer by the end of your story. A dramatic question is what will keep your audience reading.

Once J decides to commit to the MIB Agent K starts the process of deleting J’s identity. The filmmakers do a great job communicating the drastic nature of J’s decision. This is done through, again, action and an effective voice-over. J’s social security number is deleted, and his fingerprints are burned off. He dons a nondescript black suit, sunglasses, and a sick-ass Hamilton watch .

This scene is immediately followed by a threatening message sent by aliens called the Arquillians. They tell the MIB they will destroy the Earth unless J and K can deliver a galaxy. The only problem is no one knows what the galaxy is. So, we get our story question. Can J and K find and deliver the MacGuffin before the Earth is destroyed?

Read more about MacGuffins here.

- What event will push your hero into the special world?

- Once they enter the special world, what keeps them from turning back?

- What is the dramatic question you will introduce?

- How will your hero’s life change once they’ve entered the special world?

Tests, Allies, Enemies

This is stage is exactly what it sounds like. Once they’ve entered the special world, your hero will be tested. They will learn the rules of this new world. Your hero’s mentor may have to further teach your hero.

The hero will also begin collecting allies. Characters whose goals align with those of your hero’s. People who will help your hero achieve their goal. These characters may even join your hero on their quest.

And this is also the point where your hero’s enemy will reveal themselves. Now, you’ve may have hinted at, or even introduced the villain in the earlier stages. But, this is where the audience discovers how much of a threat this villain is to your hero.

Read more about creating villains here.

J and K arrive at the city morgue to investigate the body of a slain member of Arquillian royalty. While there, J encounters the villain of the film. He is lured into a standoff with Edgar. Edgar isn’t Edgar. He’s a 10 foot tall, alien cockroach wearing an “Edgar suit.”

J doesn’t know that yet, though.

Edgar has also taken a hostage. He threatens the life of Dr. Laurel Weaver who has discovered the truth about aliens living on Earth. Dr. Weaver becomes an ally of J’s as he continues his search for the Arquillian’s galaxy.

J is faced with a new test as well. Just before he dies, the Arquillian alien tells J that the galaxy is on Orion’s Belt. J must discover the meaning behind this cryptic message if he hopes to save Earth.

- Who is the villain of your story, and what is their goal?

- Who are your hero’s allies?

- How will your hero meet them? And, How do everyone’s goals align?

- How will your hero be tested? Through battle? A puzzle? An emotional trauma?

Approach to the Inmost Cave

The inmost cave is the path towards the central conflict of your story. In this section, your hero is preparing for battle. They may be regrouping with allies, going over important information, or taking a needed rest. This is also a part of the story where you may want to inject some humor.

The approach is also a moment for your audience to regroup. This is an important aspect of pacing. A fast-paced story can be very exciting for the audience, but at some point, the writer needs to tap the breaks.

This approach section gives your audience time to process the plot and consider the stakes of your conflict. This is also a good time to introduce a ticking clock, and it’s perfect for character development.

In Men, In Black the Approach the Inmost Cave involves an interview with a character called Frank the Pug. Frank is a Pug breed of dog. He’s an alien in disguise.

Frank knows important details about the conflict between the Arquillians and Edgar. This is one of the funnier scenes in an overall funny film.

Read more about alliteration here… jk.

Frank also gives J a vital clue to determine the location of the Arquillian’s galaxy. They also discover that the galaxy is an energy source and not an actual galaxy.

Finally, we have the arrival of the Arquillian battleship come to destroy Earth. They give the MIB a warning. If the galaxy is not returned in one hour the will fire on the planet. So, we have a literal ticking clock.

- Where and how will your hero slow down and regroup?

- What information or resources will they need to go into the final battle?

- How can you introduce some humor or character development into this section?

- What kind of “ticking clock” will you introduce to increase the stakes of your final act?

The Ordeal

The Ordeal is about one thing, and that’s death. Your hero must go through a life-altering challenge. This will be a conflict where the hero faces their greatest fears.

It’s essential that your audience feels as if the hero is really in danger. Make the audience question whether the hero will make it out alive. But, your story’s stakes may not be life or death, such as in a comedy or romance.

In that case the death your character experiences will be symbolic. And, your audience will believe that there’s a chance the hero won’t achieve their goal.

Through the ordeal, your hero will experience death whether that be real or symbolic. With this death, the hero will be reborn with greater powers or insight. Overall, the ordeal should be the point in which your character hits rock bottom.

The Ordeal in Men In Black comes the moment when J and K confront Edgar at the site of the World’s Fair. In the confrontation with Edgar, K is eaten alive by Edgar. At this moment J is left alone to confront death. The audience is left to wonder if J can defeat Edgar on his own.

Guided Questions

- What death will your hero confront?

- What does “rock bottom” mean for your character?

- How will your hero be changed on the other side of this death event?

Reward or Seizing the Sword

At this point in the story, your hero will earn some tangible treasure for all their trouble. This can be a physical treasure. In the context of the monomyth, this is often referred to as the elixir or sword.

However, the reward can be inwardly focused. Your hero might discover hidden knowledge or insight that helps them vanquish their foe. Or, your hero can find their confidence or some self-actualization. This reward, whatever it is, is the thing that they will take with them. It is what they earn from all their hard-fought struggles.

Once K is eaten J seems to be on his own with a massive alien cockroach. This is a pretty bad spot for the rookie agent. What’s worse is the Arquillian clock is still ticking. Edgar, the cockroach, is about to escape Earth, with the galaxy, sealing the planet’s fate.

All seems lost until J claims his reward. In this case, that reward comes in the form of an insight J has about Edgar. Being a giant cockroach, J realizes that Edgar may have a weakness for his Earth-bound counterparts. So, J kicks out a dumpster and starts to smash all the scurrying bugs under his foot.

J guesses correctly, and Edgar is momentarily distracted by J’s actions. Edgar climbs down from his ship to confront J. Agent K, who is still alive in Edgar’s stomach, can activate a gun, and blow Edgar in two. J’s reward is the knowledge that he is no longer a rookie, and he is strong enough for this job. J also captures a physical treasure. After Edgar has exploded, J finds the galaxy which Edgar had swallowed earlier in the film. In this scene, both dramatic questions are answered. The MIB can save the world. And, J is strong enough for the MIB.

- What reward will your hero win?

- A physical treasure, hidden knowledge, inner wisdom, or all of the above?

The Road Back

At this point, your hero has had some success in their quest and is close to returning to the ordinary world. Your hero has experienced a change from their time in the special world. This change might make your hero’s return difficult. Similar to when your hero crossed the threshold, your hero may need an event that forces them to return.

The road back must be a dramatic turning point that heightens stakes and changes the direction of your story. This event will also re-establish the dramatic question of your story. This act may present a final challenge for your hero before they can return home.

In Men In Black, the road backstage gets a little tricky. The film establishes that when J crosses the threshold he is not able to go back to the ordinary world. His entire identity is erased. Having J go back to his life as a detective would also undo his character growth and leave the audience feeling cheated. Luckily, the filmmakers work around this by having K return to the ordinary world rather than J.

After Edgar is defeated, K tells J that he is retiring from the MIB and that J will step in as K’s replacement. The movie establishes early that agents can retire, but only after having their memory wiped. So, K asks J to wipe his memory so that he can return to a normal life. Once again, J has to grapple with the question of whether he is strong enough for this job. Can he bring himself to wipe K’s memory and lose his mentor forever? Can he fill K’s shoes as an MIB agent?

- How will your hero have to recommit to their journey?

- What event will push your hero through their final test?

- What final test will your hero face before they return to the ordinary world?

Resurrection

This is the final act of your story. The hero will have one last glorious encounter with the forces that are set against them. This is the culminating event for your hero. Everything that has happened to your hero has prepared them for this moment.

This can also be thought of as a rebirth for your hero. A moment when they shed all the things that have held them back throughout the story. The resurrection is when your hero applies all the things they’ve learned through their journey.

The final moment can be a physical battle, or again, it can be metaphorical. This is also a moment when allies return to lend a last-minute hand. But, as with any ending of a story, you need to make sure your hero is the one who saves the day.

So, here’s where things start to get a little clumsy. There are a couple of moments that could be a resurrection for our hero J. It could be the moment he faces off with Edgar. This is right before Edgar is killed. But, it’s K that pulls the trigger and kills Edgar. Based on our explanation J needs to be the one who saves the day. Maybe by stalling for time J is the one responsible for saving the day? It’s hard to say what the filmmakers’ intention was here.

The second moment that could represent a resurrection for J might be when he wipes K’s memory. It is the final dramatic hurdle that J faces before he can become a true Man in Black. But, this moment doesn’t resolve the conflict of the film.

Notice that the Hero’s Journey framework isn’t always followed to the letter by all storytellers. We’ll get back to this point at the end of the article.

- What final challenge will your hero face?

- How will your hero use the skills they’ve used to overcome their last challenge?

- How will your hero’s allies help save the day?

Return with the Elixir

The ending of your story. Your hero returns to the ordinary world, but this time they carry with them the rewards earned during their journey. They may share these rewards with others who inhabit the ordinary world. But most important, is that you show that your hero has changed for the better.

The elixir represents whatever your hero gained on their journey. Remember, the elixir can be an actual physical reward like a treasure. But, the elixir can also be a metaphorical prize like knowledge or a feeling of fulfillment. This is a moment where your hero will return some sort of balance to the ordinary world.

Be sure to show that the journey has had a permanent effect on your hero.

In the final scene of the movie, we see that J has taken on a mentor role for Dr. Weaver, an MIB recruit now. He has physically changed- his clothes are more representative of his personality. This physical transformation is meant to show that J has fully embraced his new life and journey. No longer a rookie, J has stepped into his mentor, K’s, role.

- How will you show that your character has changed from their journey?

- What reward will they bring back to the ordinary world?

- In what way will they change the ordinary world when they return?

Should I Use the Hero’s Journey for My Story?

This is a question you should ask yourself before embarking on your journey. The Monomyth works well as a framework. This is pretty obvious when you realize how many films have used it as a plotting device.

But there’s a downside to the popularity of the Monomyth. And that’s that audiences are very familiar with the beats of this kind of story. Sure, they may not be able to describe each of the twelve sections in detail. But, audiences know, intuitively, what is going to happen in these stories. At the very least, audiences, or readers, know how these stories are going to end.

This isn’t necessarily a bad thing. If your story is exciting, well-paced, and the stakes are high, people aren’t going to mind some predictability. But, if you want to shock your readers-

(And if you’re interested in how to shock readers with a plot twist, click here. )

this might not be the best story structure. And, despite how popular it is, the hero’s journey ain’t the only game in town when it comes to story structure. And, you can always take artistic liberty with the Hero’s Journey. The fact that audiences are expecting certain beats means you have an opportunity to subvert expectations.

You can skip parts of the hero’s journey if they don’t fit your plot. With my example, Men In Black it was difficult to fit the story neatly into the hero’s journey framework. This is because aspects of the movie, like the fact that it’s a buddy comedy, don’t always jive with a hero’s journey. Agent K has an important character arch, and so he ends up killing the villain rather than J. But, K’s arch isn’t at all a hero’s journey.

The point is, don’t feel locked in by any single structure. Allow yourself some freedom to tell your story. If there’s no purpose to a resurrection stage in your story then skip it! No one is going to deduct your points.

With that said, here are a few resources on the Hero’s Journey, and some alternate plot structures you’ll want to check out!

This post contains affiliate links to products. We may receive a commission for purchases made through these links

Further Reading on Plot Structure and the Hero’s Journey

If you’d like to learn more about the Hero’s Journey, or Monomyth, why not go straight to the source? The Hero With 1000 Faces is a collection of work written by Joseph Campbell. His version of the hero’s journey has 17 stages. This is less of a writing manual and more of an exploration of the evolution of myth and storytelling through the ages.

The Seven Basic Plots , by Christopher Booker, is another academic study of storytelling by Christopher Booker. Booker identifies seven basic plots that all stories fit into. They are:

- Overcoming the Monster

- Rags to Riches

- Voyage and Return

The Snowflake Method is a teaching tool designed by Randy Ingermanson that will take you through a step-by-step process of writing a novel. The Snowflake Method boils down the novel-writing process six-step process. You will start with a single sentence and with each step you build on that sentence until you have a full-fledged novel! If you’re love processes then pick up a copy of this book today.

In The Writer’s Journey: Mythic Structure for Writers, Hollywood consultant, Christopher Vogler teaches writers how to use the Hero’s Journey to write riveting stories.

Resources:

Wikipedia- Joseph Campbell

Wikipedia- Hero With 1000 Faces

Published by John

View all posts by John

6 comments on “A Complete Guide to The Hero’s Journey (or The Monomyth)”

- Pingback: How to Create Stories with the Three-Act Structure - The Art of Narrative

- Pingback: Kishōtenketsu: Exploring The Four Act Story Structure - The Art of Narrative

- Pingback: A Definitive Guide to the Seven-Point Story Structure - The Art of Narrative

- Pingback: What are Character Archetypes? 25 Character Archetypes Explained - The Art of Narrative

- Pingback: How to use the 27 Chapter Plot Structure - The Art of Narrative

I don’t understand the use of all those pictures/graphics you threw in as I was reading. They were extremely distracting and seriously detracted from whatever message you were trying to convey.

Leave a Reply Cancel reply

Copy and paste this code to display the image on your site

Discover more from The Art of Narrative

Subscribe now to keep reading and get access to the full archive.

Type your email…

Continue reading

Improve your writing in one of the largest and most successful writing groups online

Join our writing group!

What is a Tragic Hero? Examples and How to Write Your Own

by Fija Callaghan

There’s something undeniably cathartic about the tragic hero figure. From ancient Greek performances to contemporary film and everything in between, these complex, emotionally resonant characters have entertained audiences (and taught them valuable lessons) for generations.

So what exactly do we mean by a “tragic hero”, and how do they compare with other archetypal characters? Read on for everything you need to know about how we define the classic tragic hero, with some examples and tips for writing your own.

What is a tragic hero in literature?

Tragic heroes are protagonists who fall from a state of nobility, privilege, or good fortune due to an insurmountable personal weakness. They exhibit enough virtue, compassion, or other traditionally heroic traits to make them relatable and empathetic, but meet a tragic end once their fatal flaw gets the best of them. These heroes act as cautionary tales to the audience.

For example, a tragic hero might be a main character who does everything right, but ultimately loses everything once he chooses ambition over love. Or, like Romeo in Shakespeare’s Romeo and Juliet , chooses the thrill and novelty of young love over common sense.

These characters make readers want them to succeed. And yet, we watch as they hurtle to their heartbreaking, inevitable conclusion. Their stories help us understand what happens when we allow our own weaknesses to consume us.

What’s the difference between a tragic hero and an anti-hero?

“Tragic hero” and “anti-hero” are literary terms that sometimes get conflated, but they’re not quite the same thing. You can think of a tragic hero and an anti-hero as reflections of each other: while tragic heroes are basically heroic figures with one toxic, devastating flaw, anti-heroes are figures who lack traditionally heroic qualities but are underpinned by an internal strength.

An anti-hero might be physically weak, unethical, cowardly, or self-serving. In spite of this, they demonstrate the potential for redemption and growth. Tragic heroes warn us that weakness exists even in the most promising of people. Anti-heroes show us that strength can be found even in the most unlikely of places.

Characteristics of the tragic hero

Let’s look at the key character traits that every literary tragic hero needs.

To begin, the tragic hero needs to come from a place of elevated status. They don’t need to be of literal noble birth (although this was often the case in the classic Greek tragedy, as well as in Elizabethan plays, because… don’t we all love to watch posh people behaving badly?); however, they do need to be ranked above the “average person” in some way.

They might be the most popular kid at school, or employee of the month at their job, or a prominent social media influencer, or the beloved eldest child in their family. Whatever their social parameters might be, their journey opens in a place of “This person has their life together.”

Despite the character’s elevated status, they should have enough endearing qualities that the reader wants them to succeed. They might be very kind, or charming, or they tell great stories at parties. Make sure the reader sees the humanity in this character to develop their compassion for them. Without the audience’s sympathy, the hero’s tragic downfall wouldn’t be tragic… it would just be satisfying.

A tragic flaw

Ah, the rotten core of the tragic hero’s downfall: the fatal flaw. This is the character’s one irreconcilable vice which ultimately leads to their undoing. Ambition is a common tragic flaw, but it could also be something like jealousy, insecurity, cowardice, or a desperation to be loved.

These fatal flaws will guide the hero forward, pulling them mercilessly towards their inevitable conclusion.

Like all literary protagonists, the tragic hero needs to want something. Their lives are going pretty great so far, and they would be perfect if they could only attain that one thing . A better title, a bigger house than their annoying neighbor’s, more followers, more respect, the right person to fill that emotional void.

Their pursuit and subsequent obsession for this one thing is what carries the plot of the story and erodes the character’s pristine life into a dumpster fire of regret.

Finally, like all good storytelling, the tragic hero needs conflict . Specifically, internal conflict that has them battling themselves as they hurtle forward along their damaging path. Consider Shakespeare’s Macbeth (whom we’ll look at in more detail below): he doesn’t really want to stab anybody to death, but wouldn’t life just be so much better if he was king? Plus, it’s clearly Lady M who wears the pants in that relationship.

Internal conflict helps elicit sympathy in the reader, because we can see the path the character could have taken. This makes their downfall even more tragic.

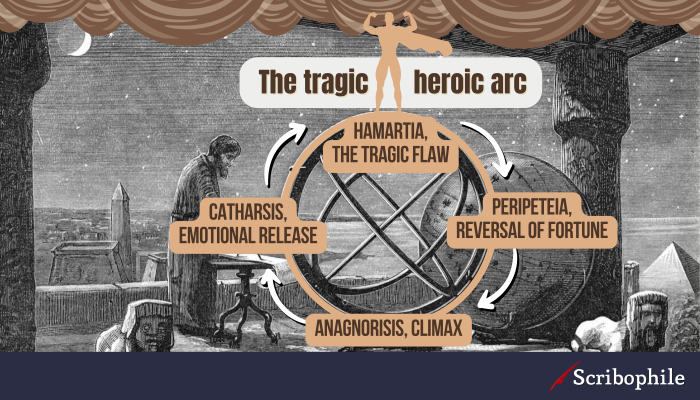

Elements of the tragic hero’s journey

The Greek philosopher Aristotle—a dude who knew a thing or two about the foundations of narrative—coined what he called the “pillars of tragedy”: elements that every tragic hero’s journey should have. These terms are useful to know when it comes to understanding the structure of a tragedy (and impressing your friends).

Hamartia is the traditional term for the hero’s fatal flaw or weakness. The word means “to err,” or “to miss the mark.” This is a characteristic or personality trait inherent in the protagonist which, when left unchecked, grows until it takes over the protagonist’s life completely.

Peripeteia means “reversal of fortune.” It’s the moment in a story when things start going downhill— fast . Although the hero hasn’t yet been completely overtaken by their fatal flaw, the reader will have a sense that the main character is starting to lose control of their carefully curated life.

Anagnorisis

Anagnorisis is a word that means “recognition,” and it’s usually the climax of the hero’s tragic arc. It’s when the main character is confronted by the reality of how spectacularly they screwed up, and are forced to acknowledge that they really only have themselves to blame.

Catharsis is a term that refers to the reader or audience’s experience with the tragic hero’s story. It’s the emotional release, or cleansing, that comes from watching the hero’s downfall. This emotional release encourages the reader to reflect on the experience and the relationship they might have to this weakness in their own lives.

Examples of tragic heroes from literature and film

Let’s look at how these traits play out in some popular examples of tragic heroes.

Shakespeare’s Macbeth

Macbeth (or The Thane, if you’re an actor ) is one of literature’s most famous tragic heroes. He’s basically a decent bloke, except for his relentless ambition. When Macbeth hears a prophecy from a trio of witches promising that he’ll one day be king, he decides to take matters into his own hands (with some encouragement from his steely-eyed wife).

Despite his success, Macbeth doesn’t have the heart of a murderer, and his guilt and grief weigh him down. Once he achieves power, however, he becomes desperate to hold onto it. His increasing ambition and subsequent paranoia ultimately lead to his undoing.

Don Draper from Mad Men

Mad Men is a television series that follows a toxic ad agency in the 1960s, and its suave, polished protagonist Don Draper may be the maddest of all. Early in the show it’s revealed that “Don Draper” is actually a stolen identity, and the man’s entire life is a façade. The fatal flaw of this modern tragic hero is his pride, and through that pride, a need to control everything and everyone around him.

Naturally, this fist-clenching approach to life does more harm than good; it eventually pushes away his friends, family, and professional relationships. By the end of the show’s seven-season run, his actions towards others have led to a nervous breakdown and complete isolation from everyone who used to believe in him.

Oedipus from Oedipus Rex

This iconic Greek tragedy by Sophocles is one of the most formative plays of all time, and we can see echoes of its themes and structure in Shakespeare’s work as well as in contemporary literature. Th title character Oedipus is a respected king who, like Macbeth, is waylaid by a perplexing prophecy: he’s fated to kill his father and marry his mother.

As one would expect, his parents aren’t thrilled with this, so they abandon their baby to the wild elements. Except of course Oedipus does grow up, never knowing who his real parents were, and you can probably imagine how swimmingly that goes.

Oedipus’s fatal flaw is his hubris: he believes himself to be above the constraints of destiny (and, thereby, above the gods). When he learns of the prophecy, he spends the rest of the play trying to outrun his fate—which, because this is ancient Greece, is exactly what sets his fate into motion.

How to write your own tragic hero

Ready to develop your own tragic hero (or tragic heroine)? Here are the essential character-building steps to take as you explore your story.

Develop your hero’s ordinary world

First, you need to develop your tragic hero’s everyday life—specifically, what they have to lose. This means their relationships, accomplishments, social network, and so forth.

Remember, your protagonist should begin from a place of relative nobility to those around them so that the reader has a sense of how far they have to fall. In order for your hero’s arc to be truly tragic, there needs to be a clear and dramatic decline in fortune. Show your reader what your hero is most proud of before you take it all away.

Isolate your hero’s tragic flaw

Your protagonist is probably a reasonably upstanding dude(ette)… except?! What’s the one weakness they’ve never quite been able to overcome? What makes them feel unsatisfied with their current state of being?

Ambition, paranoia, cowardice, casual cruelty, avarice, excessive pride, self righteousness, and internalized prejudice are all potential fatal flaws (or hamartia ) that might prove to be your hero’s undoing.

Determine what they’re fighting for

Once you know what your hero’s tragic flaw is, determine what this flaw is driving them to do and how they’re using it to fill a perceived void. They might be working towards a promotion, a milestone number of Instagram followers, a relationship with the perfect man or woman, authority over their circumstances, or some other benchmark that will make them believe that they’ve “arrived.”

This pursuit of something they believe will make them happy (even though it probably won’t) is what drives the story’s plot, leads to the hero’s suffering, and ultimately brings about their own destruction.

Lead them to a reversal of fortune

That’s the peripeteia , remember? The hero’s quest is steadily gaining ground, until it suddenly skids dramatically off course. It might start with something small going wrong—a miscalculation, a misunderstanding, a bad review, one bad choice—which then snowballs as the tragic hero responds to the event and starts making things a lot worse.

Now, the hero has to scramble to regain the control they once had as the ground starts to crumble beneath their feet.

Watch them crash and burn

The hardest, yet most satisfying, thing about watching the tragic hero’s life collapse is knowing that their fate was sealed almost from the beginning. Once the protagonist proved that they were unable to rise about their fatal flaw, it was only a matter of time before they lost their grip and descended into a hell of their own making.

This is where the catharsis comes in. The reader or listener is able to learn from the hero’s mistakes and reflect on their own weaknesses and strengths.

In literature, tragic heroes make us think

In an age when hope and positivity is more important than ever, does storytelling still have a place for tragedy? Tragic heroes remain resonant and effective because they teach valuable lessons and help give readers (and writers!) an emotional release. With these tips, you can take readers on their own tragic journey—and then safely close the page once it’s over, no Oedipal eye-gouging required.

Get feedback on your writing today!

Scribophile is a community of hundreds of thousands of writers from all over the world. Meet beta readers, get feedback on your writing, and become a better writer!

Join now for free

Related articles

The Sidekick Archetype: Everything You Need to Know

What Is an Anti-Villain? Making the Bad Guys (Kind Of) Good Again

What is the Threshold Guardian Archetype? With Tips for Creating Your Own

What is a Flat Character? And When To Use Them In Your Writing

What is Head Hopping, and How to Avoid This Writing Mistake

What Are Minor Characters? With Tips on Writing Them

Tragic Hero

Tragic Hero Definition

What is a tragic hero? Here’s a quick and simple definition:

A tragic hero is a type of character in a tragedy , and is usually the protagonist . Tragic heroes typically have heroic traits that earn them the sympathy of the audience, but also have flaws or make mistakes that ultimately lead to their own downfall. In Shakespeare's Romeo and Juliet , Romeo is a tragic hero. His reckless passion in love, which makes him a compelling character, also leads directly to the tragedy of his death.

Some additional key details about tragic heroes:

- The idea of the tragic hero was first defined by the ancient Greek philosopher Aristotle based on his study of Greek drama.

- Despite the term "tragic hero," it's sometimes the case that tragic heroes are not really heroes at all in the typical sense—and in a few cases, antagonists may even be described as tragic heroes.

Tragic Hero Pronunciation

Here's how to pronounce tragic hero: tra -jik hee -roh

The Evolution of the Tragic Hero

Tragic heroes are the key ingredient that make tragedies, well, tragic. That said, the idea of the characteristics that make a tragic hero have changed over time.

Aristotle and the Tragic Hero

The ancient Greek philosopher Aristotle was the first to define a "tragic hero." He believed that a good tragedy must evoke feelings of fear and pity in the audience, since he saw these two emotions as being fundamental to the experience of catharsis (the process of releasing strong or pent-up emotions through art). As Aristotle puts it, when the tragic hero meets his demise, "pity is aroused by unmerited misfortune, fear by the misfortune of a man like ourselves."

Aristotle strictly defined the characteristics that a tragic hero must have in order to evoke these feelings in an audience. According to Aristotle, a tragic hero must:

- Be virtuous: In Aristotle's time, this meant that the character should be a noble. It also meant that the character should be both capable and powerful (i.e. "heroic"), and also feel responsible to the rules of honor and morality that guided Greek culture. These traits make the hero attractive and compelling, and gain the audience's sympathy.

- Be flawed: While being heroic, the character must also have a tragic flaw (also called hamartia ) or more generally be subject to human error, and the flaw must lead to the character's downfall. On the one hand, these flaws make the character "relatable," someone with whom the audience can identify. Just as important, the tragic flaw makes the tragedy more powerful because it means that the source of the tragedy is internal to the character, not merely some outside force. In the most successful tragedies, the tragic hero's flaw is not just a characteristic they have in addition to their heroic qualities, but one that emerges from their heroic qualities—for instance, a righteous quest for justice or truth that leads to terrible conclusions, or hubris (the arrogance that often accompanies greatness). In such cases, it is as if the character is fated to destruction by his or her own nature.

- Suffer a reversal of fortune: The character should suffer a terrible reversal of fortune, from good to bad. Such a reversal does not merely mean a loss of money or status. It means that the work should end with the character dead or in immense suffering, and to a degree that outweighs what it seems like the character deserved.

To sum up: Aristotle defined a tragic hero rather strictly as a man of noble birth with heroic qualities whose fortunes change due to a tragic flaw or mistake (often emerging from the character's own heroic qualities) that ultimately brings about the tragic hero's terrible, excessive downfall.

The Modern Tragic Hero

Over time, the definition of a tragic hero has relaxed considerably. It can now include

- Characters of all genders and class backgrounds. Tragic heroes no longer have to be only nobles, or only men.

- Characters who don't fit the conventional definition of a hero. This might mean that a tragic hero could be regular person who lacks typical heroic qualities, or perhaps even a villainous or or semi-villainous person.

Nevertheless, the essence of a tragic hero in modern times maintains two key aspects from Aristotle's day:

- The tragic hero must have the sympathy of the audience.

- The tragic hero must, despite their best efforts or intentions, come to ruin because of some tragic flaw in their own character.

Tragic Hero, Antihero, and Byronic Hero

There are two terms that are often confused with tragic hero: antihero and Byronic hero.

- Antihero : An antihero is a protagonist who lacks many of the conventional qualities associated with heroes, such as courage, honesty, and integrity, but still has the audience's sympathy. An antihero may do the right thing for the wrong reason. Clint Eastwood's character in the western film, The Good, the Bad, and the Ugly , is fundamentally selfish. He digs up graves to look for gold and kills anyone who gets in his way, so he's definitely a bad guy. But as an antihero, he's not completely rotten: he also shows a little sympathy for dying soldiers in the bloody war going on around him, and at the end of the film he acts mercifully in choosing not to kill a man who previously tried to kill him. He does a few good things, but only as long as it suits him—so he's a classic antihero.

- Byronic hero : A Byronic hero is a variant of the antihero. Named after the characters in the poetry of Lord Byron, the Byronic hero is usually a man who is an intelligent, emotionally sensitive, introspective, and cynical character. While Byronic heroes tend to be very charismatic, they're deeply flawed individuals, who might do things that are generally thought of as socially unacceptable because they are at odds with mainstream society. A Byronic hero has his own set of beliefs and will not yield for anyone. While it might not be initially apparent, deep down, the Byronic hero is also quite selfish.

According to the modern conception of a tragic hero, both an antihero and a Byronic hero could also be tragic heroes. But in order for a tragic hero to exist, he or she has to be part of a tragedy with a story that ends in death or ruin. Antiheroes and Byronic heroes can exist in all sorts of different genres, however, not just tragedies. An antihero in an action movie—for instance Deadpool, in the first Deadpool movie—is not a tragic hero because his story ends generally happily. But you could argue that Macbeth is a kind of antihero (or at least an initial hero who over time becomes an antihero), and he is very definitely also a tragic hero.

Tragic Hero Examples

Tragic heroes in drama.

The tragic hero originated in ancient Greek theater, and can still be seen in contemporary tragedies. Even though the definition has expanded since Aristotle first defined the archetype, the tragic hero's defining characteristics have remained—for example, eliciting sympathy from the audience, and bringing about their own downfall.

Oedipus as Tragic Hero in Oedipus Rex

The most common tragic flaw (or hamartia ) for a tragic hero to have is hubris , or excessive pride and self-confidence. Sophocles' tragic play Oedipus Rex contains what is perhaps the most well-known example of Aristotle's definition of the tragic hero—and it's also a good example of hubris. The play centers around King Oedipus, who seeks to rid the city he leads of a terrible plague. At the start of the play, Oedipus is told by a prophet that the only way to banish the plague is to punish the man who killed the previous king, Laius. But the same prophet also reports that Oedipus has murdered his own father and married his mother. Oedipus refuses to believe the second half of the prophecy—the part pertaining to him—but nonetheless sets out to find and punish Laius's murderer. Eventually, Oedipus discovers that Laius had been his father, and that he had, in fact, unwittingly killed him years earlier, and that the fateful event had led directly to him marrying his own mother. Consequently, Oedipus learns that he himself is the cause of the plague, and upon realizing all this he gouges his eyes out in misery (his wife/mother also kills herself).

Oedipus has all the important features of a classical tragic hero. Throughout the drama, he tries to do what is right and just, but because of his tragic flaw (hubris) he believes he can avoid the fate given to him by the prophet, and as a result he brings about his own downfall.

Willy Loman as Tragic Hero in Death of a Salesman

Arthur Miller wrote his play Death of a Salesman with the intent of creating a tragedy about a man who was not a noble or powerful man, but rather a regular working person, a salesman.

The protagonist of Death of a Salesman, Willy Loman, desperately tries to provide for his family and maintain his pride. Willy has high expectations for himself and for his children. He wants the American Dream, which for him means financial prosperity, happiness, and good social standing. Yet as he ages he finds himself having to struggle to hold onto the traveling salesman job at the company to which he has devoted himself for decades. Meanwhile, the prospects for his sons, Biff and Happy, who seemed in high school to have held such promise, have similarly fizzled. Willy cannot let go of his idea of the American Dream nor his connected belief that he must as an American man be a good provider for his family. Ultimately, this leads him to see himself as more valuable dead than alive, and he commits suicide so his family can get the insurance money.

Willy is a modern tragic hero. He's a good person who means well, but he's also deeply flawed, and his obsession with a certain idea of success, as well as his determination to provide for his family, ultimately lead to his tragic death.

Tragic Heroes in Literature

Tragic heroes appear all over important literary works. With time, Aristotle's strict definition for what makes a tragic hero has changed, but the tragic hero's fundamental ability to elicit sympathy from an audience has remained.

Jay Gatsby as Tragic Hero in The Great Gatsby

The protagonist of F. Scott Fitzgerald's The Great Gatsby , is Jay Gatsby, a young and mysterious millionaire who longs to reunite with a woman whom he loved when he was a young man before leaving to fight in World War I. This woman, Daisy, is married, however, to a man named Tom Buchanan from a wealthy old money family. Gatsby organizes his entire life around regaining Daisy: he makes himself rich (through dubious means), he rents a house directly across a bay from hers, he throws lavish parties in the hopes that she will come. The two finally meet again and do begin an affair, but the affair ends in disaster—with Gatsby taking responsibility for driving a car that Daisy was in fact driving when she accidentally hit and killed Tom's mistress (named Myrtle), Daisy abandoning Gatsby and returning to Tom, and Gatsby getting killed by Myrtle's husband.

Gatsby's downfall is his unrelenting pursuit of a certain ideal—the American Dream—and a specific woman who he thinks fits within this dream. His blind determination makes him unable to see both that Daisy doesn't fit the ideal and that the ideal itself is unachievable. As a result he endangers himself to protect someone who likely wouldn't do the same in return. Gatsby is not a conventional hero (it's strongly implied that he made his money through gambling and other underworld activities), but for the most part his intentions are noble: he seeks love and self-fulfillment, and he doesn't intend to hurt anyone. So, Gatsby would be a modernized version of Aristotle's tragic hero—he still elicits the audience's sympathy—even if he is a slightly more flawed version of the archetype.

Javert as Tragic Hero in Victor Hugo's Les Misérables

Javert is a police detective, obsessed with law and order, and Les Misérables' primary antagonist. The novel contains various subplots but for the most part follows a character named Jean Valjean, a good and moral person who cannot escape his past as an ex-convict. (He originally goes to prison for stealing a loaf of bread to help feed his sister's seven children.) After Valjean escapes from prison, he changes his name and ends up leading a moral and prosperous life, becoming well-known for the ways in which he helps the poor.

Javert, known for his absolute respect for authority and the law, spends many years trying to find the escaped convict and return him to prison. After Javert's lifelong pursuit leads him to Valjean, though, Valjean ends up saving Javert's life. Javert, in turn, finds himself unable to arrest the man who showed him such mercy, but also cannot give up his devotion to justice and the law. In despair, he commits suicide. In other words: Javert's strength and righteous morality lead him to his destruction.

While Javert fits the model of a tragic hero in many ways, he's an unconventional tragic hero because he's an antagonist rather than the protagonist of the novel (Valjean is the protagonist). One might then argue that Javert is a "tragic figure" or "tragic character" rather than a "tragic hero" because he's not actually the "hero" of the novel at all. He's a useful example, though, because he shows just how flexible the idea of a "tragic hero" can be, and how writers play with those ideas to create new sorts of characters.

Additional Examples of Tragic Heroes

- Macbeth: In Shakespeare's Macbeth , the main character Macbeth allows his (and his wife's) ambition to push him to murder his king in order to fulfill a prophecy and become king himself. Macbeth commits his murder early in the play, and from then on his actions become bloodier and bloodier, and he becomes more a villain than a hero. Nonetheless, he ends in death, with his wife also dead, and fully realizing the emptiness of his life. Macbeth is a tragic hero, but the play is interesting in that his fatal flaw or mistake occurs relatively early in the play, and the rest of the play shows his decline into tragedy even as he initially seems to get what he seeks (the throne).

- Michael Corleone: The main character of the Godfather films, Michael Corleone can be said to experience a tragic arc over the course of the three Godfather movies. Ambition and family loyalty push him to take over his mafia family when he had originally been molded by his father to instead "go clean." Michael's devotion to his family then leads him to murder his enemies, kills his betraying brother, and indirectly leads to the deaths of essentially all of his loved ones. He dies, alone, thinking of his lost loves , a tragic antihero.

- Okonkwo: In Chinua Achebe's Things Fall Apart , Okonkwo is a man of great strength and will, and these heroic traits make him powerful and wealthy in his tribe. But his devotion to always appearing strong and powerful also lead him to alienate his son, break tribal tradition in a way that leads to his exile from the tribe, and to directly confront white missionaries in a way that ultimately leads him to commit suicide. Okonkwo's devotion to strength and power leads to his own destruction.

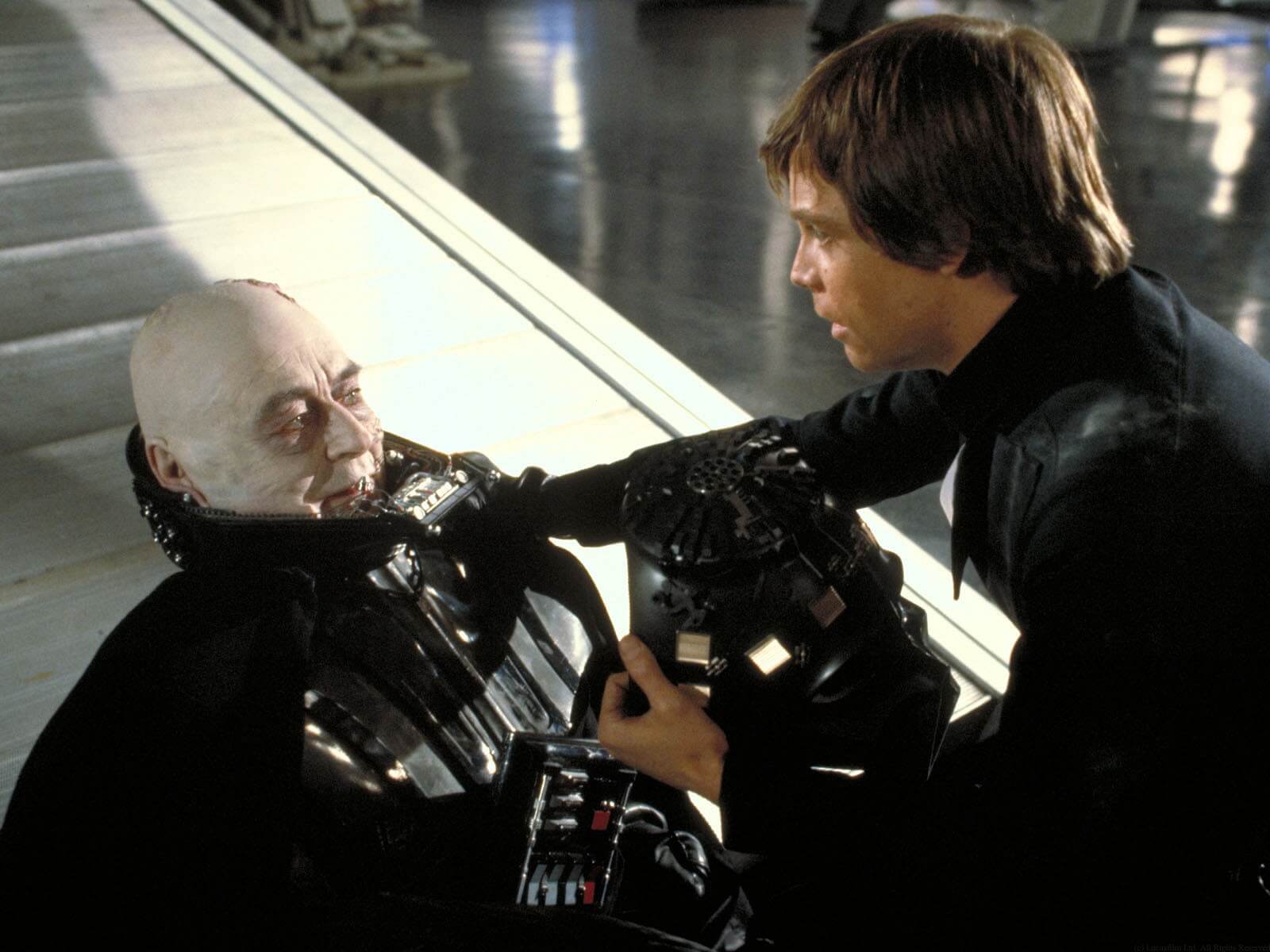

- Anakin Skywalker: The three prequel Star Wars movies (episodes I, II, and III) can be seen as an attempt to frame Anakin Skywalker into a tragic hero. Anakin is both powerful in the force and a prophesied "chosen one," but his ambition and desire for order and control lead him to abandon and kill fellow Jedi, inadvertently kill his own wife, and to join the dark side of the force and become a kind of enforcer for the Emperor. Anakin, as Darth Vader, is alone and full of such shame and self-hatred that he can see no other option but to continue on his path of evil. This makes him a tragic hero. Having said all that, some would argue that the first three Star Wars movies aren't well written or well acted enough to truly make Anakin a tragic hero (does Anakin really ever have the audience's sympathy given his bratty whininess?), but it's clear that he was meant to be a tragic hero.

What's the Function of a Tragic Hero in Literature?

Above all, tragic heroes put the tragedy in tragedies—it is the tragic hero's downfall that emotionally engages the audience or reader and invokes their pity and fear. Writers therefore use tragic heroes for many of the same reasons they write tragedies—to illustrate a moral conundrum with depth, emotion, and complexity.

Besides this, tragic heroes serve many functions in the stories in which they appear. Their tragic flaws make them more relatable to an audience, especially as compared to a more conventional hero, who might appear too perfect to actually resemble real people or draw an emotional response from the audience. Aristotle believed that by watching a tragic hero's downfall, an audience would become wiser when making choices in their own lives. Furthermore, tragic heroes can illustrate moral ambiguity, since a seemingly desirable trait (such as innocence or ambition) can suddenly become a character's greatest weakness, bringing about grave misfortune or even death.

Other Helpful Tragic Hero Resources

- The Wikipedia Page for Tragic Hero : A helpful overview that mostly focuses on the history of term.

- The Dictionary Definition of Tragic Hero : A brief and basic definition.

- A one-minute, animated explanation of the tragic hero.

- Is Macbeth a Tragic Hero? This video explains what a tragic hero is, using Macbeth as an example .

- PDFs for all 136 Lit Terms we cover

- Downloads of 1916 LitCharts Lit Guides

- Teacher Editions for every Lit Guide

- Explanations and citation info for 40,380 quotes across 1916 books

- Downloadable (PDF) line-by-line translations of every Shakespeare play

- Protagonist

- Deus Ex Machina

- Anadiplosis

- Climax (Figure of Speech)

- Anthropomorphism

- Alliteration

- Round Character

- Juxtaposition

- Flat Character

What is a Tragic Hero?

Are you preparing to teach the hero’s journey ? As we all know, the journey doesn’t always go as planned. Enter the tragic hero. Consider this your guide to all things tragic heroes, from unpacking the definition, identifying the telltale characteristics, and discussing the significance of tragic heroes in storytelling.

Tragic Hero Definition

A tragic hero is a central character, typically the protagonist, who, despite their noble traits, characteristics, or choices, is ultimately doomed by a fatal flaw or poor judgment. Therefore, rather than saving the day, tragic heroes face an unfortunate fate. This downfall often leads to some sort of tragedy and, in many cases, their own death. (Whomp whomp.)

The key to a tragic hero’s complex (and appealing) characterization lies in the balance between positive and negative traits. Therefore, instead of being viewed as the hated enemy, they often earn sympathy or compassion from the audience as they navigate the consequences of their dooming flaw(s). The result? A compelling character that hooks the audience into the plotline. The tragic hero is a popular archetype found in everything from ancient dramas to classic literature to modern movies—and everything in between.

Tragic Hero Pronunciation

Tragic hero is a phrase comprised of two two-syllable words and is pronounced like: TRAH-jik HE-roh

What are the Characteristics of a Tragic Hero?

We can thank the ancient Greek philosopher Aristotle for the term “tragic hero.” After a deep analysis of Greek drama, he started to notice certain characteristics in successful and emotionally evocative tragedies. These observations became the foundation for the essential elements and characteristics that define this archetype in literature. These traits contribute to the complexity and depth of the character, as well as their ultimate fate.

According the Aristotle, a classic tragic hero possesses the following characteristics:

1. Possess Noble Qualities

Tragic heroes often show signs of literal and figurative nobility. For starters, many come from privileged backgrounds or hold high social status within the story’s world, raising the stakes of their actions throughout the story and underscoring the significance of their downfall. However, it also refers to the admirable traits such as courage or integrity that these characters possess. Ultimately, the possession of noble qualities enriches the character development of the tragic hero while highlighting the complexities of human nature.

2. Have a Tragic Flaw (Hamartia)

This tragic flaw is a personal trait or characteristic that leads to the character’s eventual downfall. The character’s shortcomings and flaws contrast their noble qualities, heightening the dramatic tension throughout the story and underscoring the tragic irony of the hero’s fate. Common examples of Hamartia include hubris (excessive pride), ambition, greed, and jealousy.

3. Suffer a Reversal of Fortune (Peripeteia)

A sudden reversal of fortune reveals a dramatic shift in the character’s circumstances. Often brought about by their own actions or choices, this change marks the beginning of their downfall and descent into tragic territory.

4. Face a Tough Recognition (Anagnorisis)

This is when the tragic hero realizes (or, as Aristotle would say, experiences anagnorisis). This is a crucial turning point in the narrative when the hero gains insight into their situation, finally recognizing the consequences of their actions. Unfortunately, this self-awareness is not enough to reverse their tragic fate.

5. Experience a Tragic Outcome

While this outcome doesn’t have to be death (although a common move in tragedies), it does have to feel unfortunate and tragic in some way. However, the extent of the character’s suffering should exceed their mistake, creating a sense of injustice.

6. Evoke Catharsis in the Audience

Through witnessing the tragic hero’s struggles and ultimate downfall, the audience experiences a profound emotional release called catharsis. These feelings of pity, sadness, fear, or regret trigger the audience to consider the complexities of the human condition.

The Modern Tragic Hero

While Aristotle’s concept of the tragic hero remains influential to this day, modern interpretations of tragic heroes may differ from those that the ancient Greek philosopher studied. For example, while a classic tragic hero boasts characteristics like noble birth and a singular tragic flaw, modern tragic heroes encompass diverse backgrounds, identities, and experiences.

While the essence of the tragic hero is the same (tragic flaw, reversal of fate, tragic outcome, and catharsis), modern dramas reflect contemporary cultural and social issues. This shift offers insights into the complexities of modern life and moral dilemmas relevant to today’s audiences, making the stories more appealing, compelling, and relatable.

What it’s NOT: Tragic Hero vs. Antihero

Many people get confused between tragic heroes and antihero heroes. However, it’s essential to understand the differences between the two as they represent contrasting character archetypes, and each serves a different purpose in a narrative.

Let’s unpack the differences below:

- Tragic Hero: Despite their flaws, tragic heroes possess classic “heroic” qualities, such as courage, honesty, and integrity. Because of these redeeming traits, such characters can draw a sense of empathy from the audience when they experience their downfall and, ultimately, face their tragic outcome. While their downfall is a result of their own actions or decisions, the audience still feels a sense of sorrow or sympathy.

- Anti-Hero: Anti-heroes lack traditional heroic attributes, defying any of the stereotypes and redeemable qualities we think of when we hear “hero.” In fact, antiheroes may even engage in morally questionable or straight-up villainous behavior. While often cynical and showcases instances of poor judgment or disregard for rules, these characters offer a unique perspective as they challenge the status quo. Oftentimes, these characters underscore critiques of societal norms, values, or institutions, leading the audience to face uncomfortable truths and ethical dilemmas—and saving themselves from being classified as villains.

Neither tragic heroes nor antiheroes fit the mold of a classic hero. However, they both provide valuable insights into human nature and the complexities of moral decision-making. While they may be two different character archetypes, both have a way of captivating an audience, elevating the sense of drama, and inspiring meaningful reflection around ethics, morals, and identity.

Why Do Writers Use Tragic Heroes in Their Stories?

Tragic heroes are what make tragedies so… tragic. But it’s about more than having readers gasp at the dreadful demise of a (somewhat) redeemable character. Authors use tragic heroes to add depth and complexity to their narratives, opening the doors for exploring profound themes and emotions connected to life and the human experience.

They help create that sense that readers find themselves between a rock and a hard place, feeling bad for a character whose demise is of their own doing. Sounds like a recipe for a compelling narrative if you ask me!

Here is a breakdown of some of the ways a tragic hero contributes to a narrative:

- Explores Human Nature: By portraying characters who possess noble qualities but are ultimately flawed, writers can offer nuanced insights into the human condition, fostering empathy and understanding among the audience.

- Increases Emotional Engagement: Through witnessing the hero’s struggles and ultimate demise, audiences experience a profound emotional and psychological impact, fostering a deeper connection to and reflection on the story and its themes.

- Examines Morality and Fate: By confronting ethical dilemmas and facing the consequences of their actions, tragic heroes lead audiences down a path of reflecting on existential themes and considering questions about morality, free will, and fate.

- Adds Depth and Complexity: The inclusion of a tragic hero adds depth and complexity to the narrative, offering layers of meaning and leaving room for multiple interpretations while creating an enriching experience for readers.

- Creates Universal Relevance: Tragic heroes resonate with audiences because they speak to universal truths about the human condition, no matter when the story was written or takes place.

Tips for Teaching Tragic Heroes

- Start with Engaging Examples: Introduce students to classic tragic heroes using engaging excerpts or summaries to pique students’ interest and spark engaging classroom discussions about the characteristics of tragic heroes.

- Analyze Character Traits: Encourage students to analyze the traits of tragic heroes, including their noble qualities, fatal flaws, and moments of recognition. Provide opportunities for close reading and textual analysis, guiding students’ analysis.

- Track the Character’s Journey: Help students stay organized while identifying a tragic hero by paying attention to the protagonist’s journey throughout the story. Have them note any significant changes in fortune or circumstances, signifying a transition from success to adversity.

- Incorporate Multimedia Resources: Engage students with examples of tragic heroes by showing film adaptations of classic texts or watching video clips referencing examples from pop culture. Not only will this help pique student interest, but it will also help provide diverse perspectives on tragic heroes, too.

- Promote Critical Thinking: Dive deeper by posing open-ended questions about character motivations and moral dilemmas. Consider exploring ethical dilemmas and moral ambiguities using pre-reading activities , like anticipation guides or a game of Four Corners.

- Foster Empathy and Reflection: Prompt students to consider the emotional experiences of tragic heroes and the impact of their stories on the audience by facilitating discussions about the story’s themes and the power of storytelling on readers’ emotions.

Examples of Tragic Heroes in Literature

1. hamlet as a tragic hero in shakespeare’s hamlet.

Hamlet is a classic tragic hero, as are many of the protagonists in Shakespeare’s tragedies. As the prince of Denmark, he holds a position of high social standing and has a lot of potential ahead of him. Of course, this makes his tragic downfall all the more… well, tragic. Hamlet’s fatal flaw is his indecisiveness and procrastination.

Rather than seeking vengeance against his father’s murderer (and Hamlet’s uncle), King Claudius, when the opportunity arises, Hamlet gets caught up in internal conflicts and indecision. (Missed opportunity #1.) A handful of unfortunate deaths and indecisions later, Hamlet eventually manages to kill his father’s murderer, but not until he is on the brink of death himself.

2. Jay Gatsby as a Tragic Hero in The Great Gatsby

Even the Great Gatsby himself isn’t immune to a tragic downfall of his own doing. Jay Gatsby is a tragic hero with the flaw of idealism, a trait that gets in his way of achieving true love and happiness. Thanks to Gatsby’s unwavering belief in the possibility of recreating the past, he is blind to the reality before him.

He fails to see Daisy for who she really is and cannot comprehend that the past is in the past—and cannot be resumed in the present despite his “new money” status. His obsessive pursuit of wealth and status, driven by his desire to win Daisy’s love, ultimately leads to his downfall and, ultimately, his death.

3. John Proctor as a Tragic Hero in The Crucible

John Proctor isn’t an evil-spirited man. Did he succumb to lust? Yes. However, his eventual demise all stems from his fatal flaw of pride. John’s pride is no secret throughout the play. He expresses it to his wife, his mistress (Abigail), and his fellow townspeople. His pride gets the best of him when he is reluctant to confess his sin of adultery–even when it could save his life. Instead of confessing his act of adultery, he tries to focus on Abigail’s poor character.

In the end, he values his integrity and his reputation above all else. As a result, he sticks to his commitment to preserve his good name, ultimately leading to his arrest, conviction, and eventual hanging during the Salem witch trials.

More tragic hero examples from classic and popular literature:

- Peter Pan from J. M. Barrie’s Peter and Wendy : Peter Pan is a tragic hero thanks to his refusal to grow up and accept responsibility. His desire to remain young and carefree leads to his loneliness and keeps him from experiencing (and enjoying) life to the fullest.

- Anakin Skywalker from the Star Wars franchise : Before becoming Darth Vader, Anakin Skywalker was a boy with the fatal flaws of fear and attachment. Unfortunately, he loses sight of what he was once fighting for (love) and turns to the Dark Side.

- Macbeth from Shakespeare’s Macbeth : Macbeth’s fatal flaw of ambition pushes him to kill others to hasten his position as king. Ironically, the decisions he makes to secure his kingship ultimately lead to his death.

- Romeo Montague from Shakespeare’s Romeo and Juliet : Romeo’s impulsivity leads him to let his emotions control his rash decision-making. Ultimately, these sudden and emotionally driven decisions lead to tragic misunderstandings and death, including his own.

Additional Resources for Teaching Tragic Hero

Help students track the tragic hero’s characterization with this downloadable STEAL chart .

Show students this list of “The 10 Most Tragic Heroes in Movie History”

Darth Vader: Villain or Tragic Hero? Have students decide after reading this article .

Unpack the tragic hero archetype with the following videos:

- Dive into “a host of heroes” with this TED-Ed video

- Explore the allure of tragedies in storytelling

- Help students understand Hamartia with this video full of modern examples

Leave a Reply Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

Holiday Savings

cui:common.components.upgradeModal.offerHeader_undefined

The hero's journey: a story structure as old as time, the hero's journey offers a powerful framework for creating quest-based stories emphasizing self-transformation..

Table of Contents

Holding out for a hero to take your story to the next level?

The Hero’s Journey might be just what you’ve been looking for. Created by Joseph Campbell, this narrative framework packs mythic storytelling into a series of steps across three acts, each representing a crucial phase in a character's transformative journey.

Challenge . Growth . Triumph .

Whether you're penning a novel, screenplay, or video game, The Hero’s Journey is a tried-and-tested blueprint for crafting epic stories that transcend time and culture. Let’s explore the steps together and kickstart your next masterpiece.

What is the Hero’s Journey?

The Hero’s Journey is a famous template for storytelling, mapping a hero's adventurous quest through trials and tribulations to ultimate transformation.

What are the Origins of the Hero’s Journey?

The Hero’s Journey was invented by Campbell in his seminal 1949 work, The Hero with a Thousand Faces , where he introduces the concept of the "monomyth."

A comparative mythologist by trade, Campbell studied myths from cultures around the world and identified a common pattern in their narratives. He proposed that all mythic narratives are variations of a single, universal story, structured around a hero's adventure, trials, and eventual triumph.

His work unveiled the archetypal hero’s path as a mirror to humanity’s commonly shared experiences and aspirations. It was subsequently named one of the All-Time 100 Nonfiction Books by TIME in 2011.

How are the Hero’s and Heroine’s Journeys Different?

While both the Hero's and Heroine's Journeys share the theme of transformation, they diverge in their focus and execution.

The Hero’s Journey, as outlined by Campbell, emphasizes external challenges and a quest for physical or metaphorical treasures. In contrast, Murdock's Heroine’s Journey, explores internal landscapes, focusing on personal reconciliation, emotional growth, and the path to self-actualization.

In short, heroes seek to conquer the world, while heroines seek to transform their own lives; but…

Twelve Steps of the Hero’s Journey

So influential was Campbell’s monomyth theory that it's been used as the basis for some of the largest franchises of our generation: The Lord of the Rings , Harry Potter ...and George Lucas even cited it as a direct influence on Star Wars .

There are, in fact, several variations of the Hero's Journey, which we discuss further below. But for this breakdown, we'll use the twelve-step version outlined by Christopher Vogler in his book, The Writer's Journey (seemingly now out of print, unfortunately).

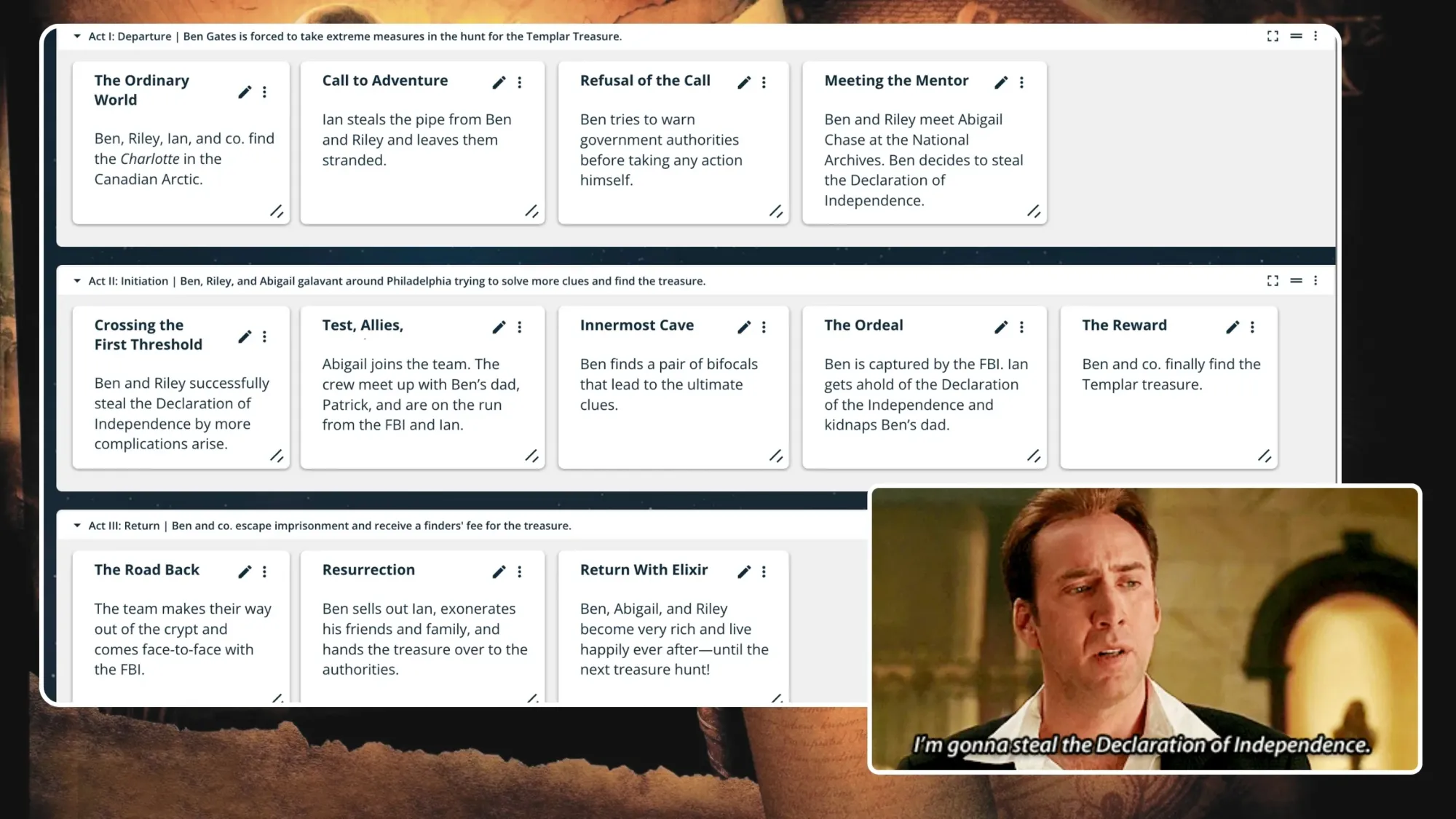

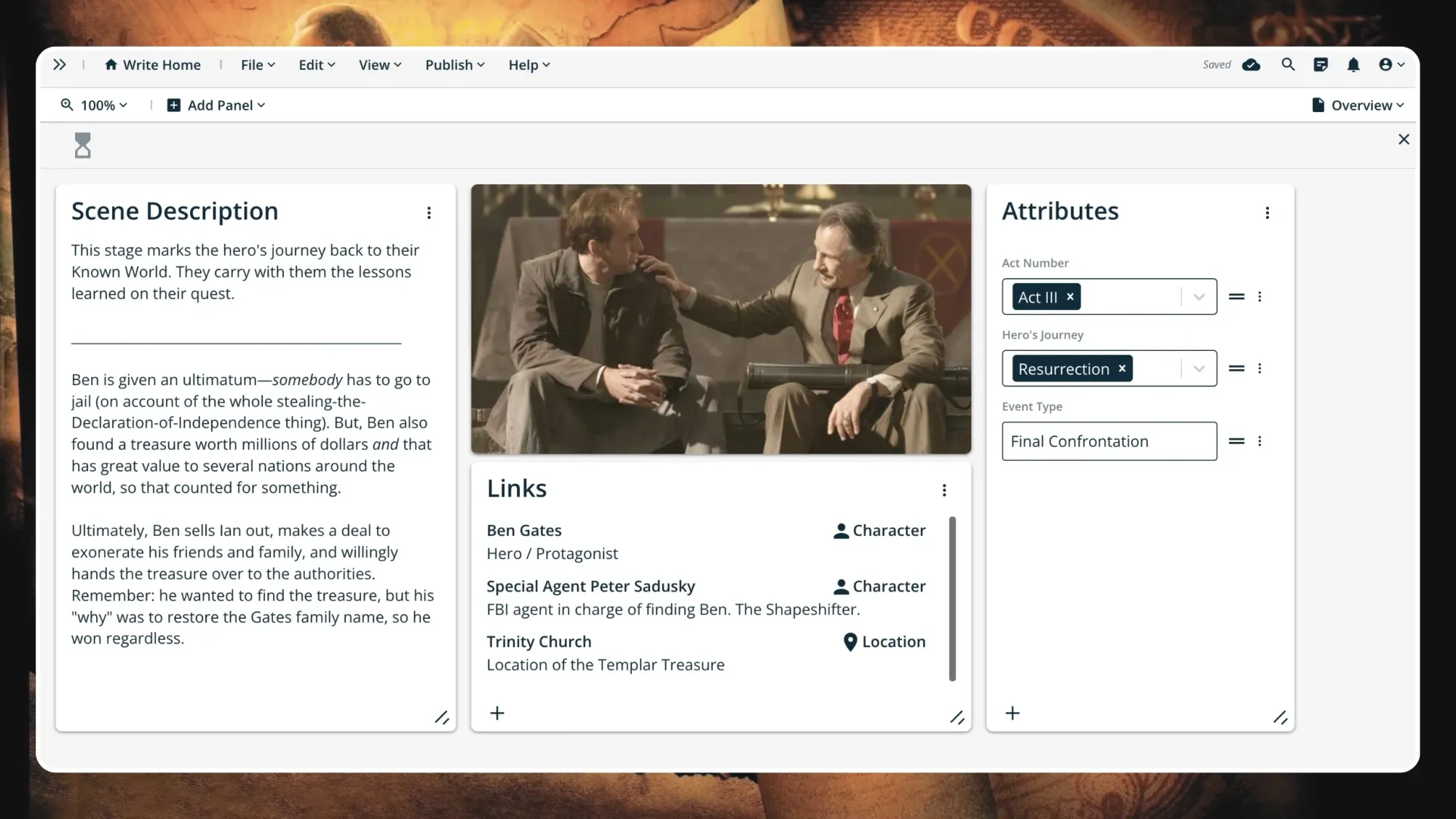

You probably already know the above stories pretty well so we’ll unpack the twelve steps of the Hero's Journey using Ben Gates’ journey in National Treasure as a case study—because what is more heroic than saving the Declaration of Independence from a bunch of goons?

Ye be warned: Spoilers ahead!

Act One: Departure

Step 1. the ordinary world.

The journey begins with the status quo—business as usual. We meet the hero and are introduced to the Known World they live in. In other words, this is your exposition, the starting stuff that establishes the story to come.

National Treasure begins in media res (preceded only by a short prologue), where we are given key information that introduces us to Ben Gates' world, who he is (a historian from a notorious family), what he does (treasure hunts), and why he's doing it (restoring his family's name).

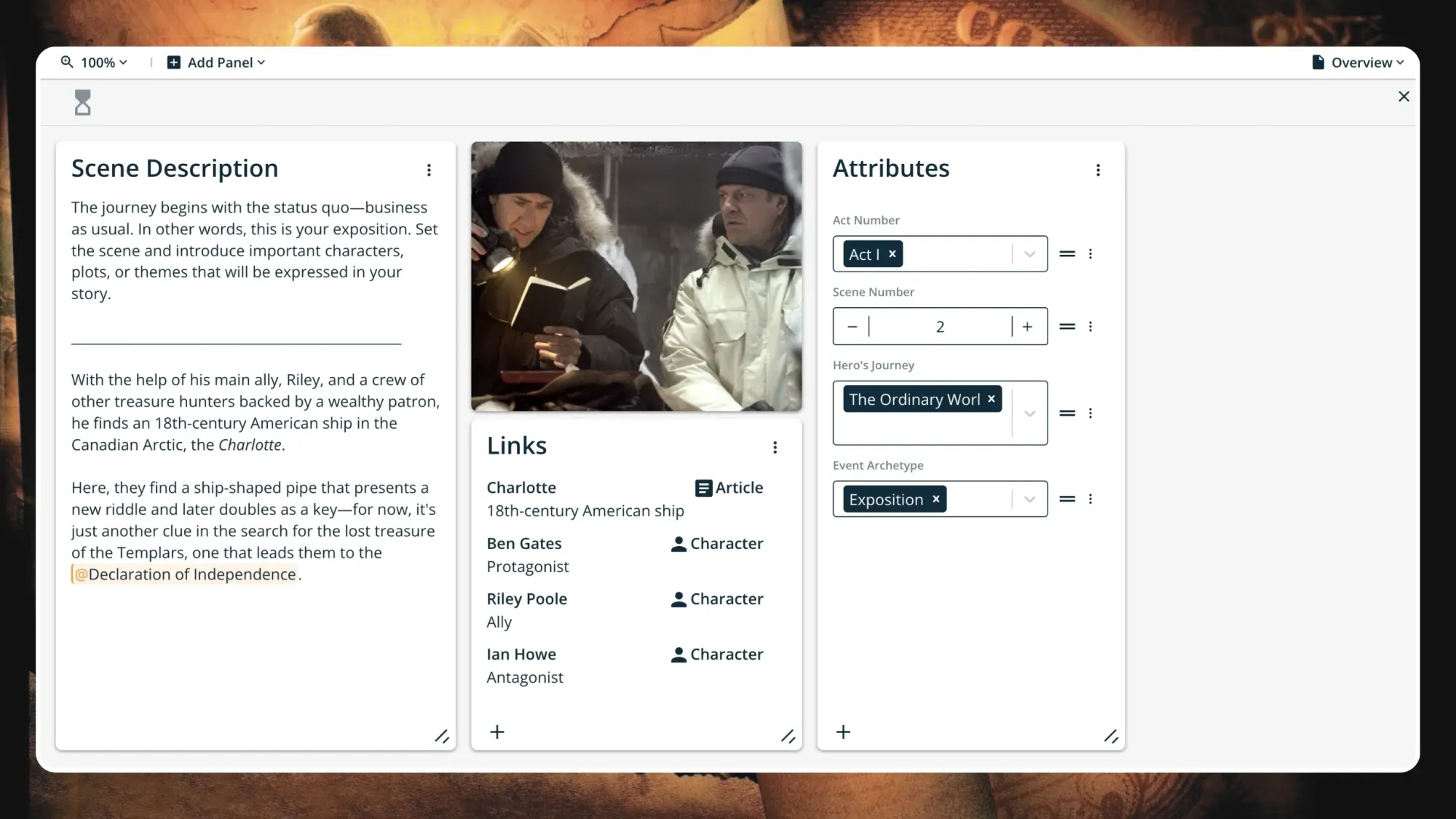

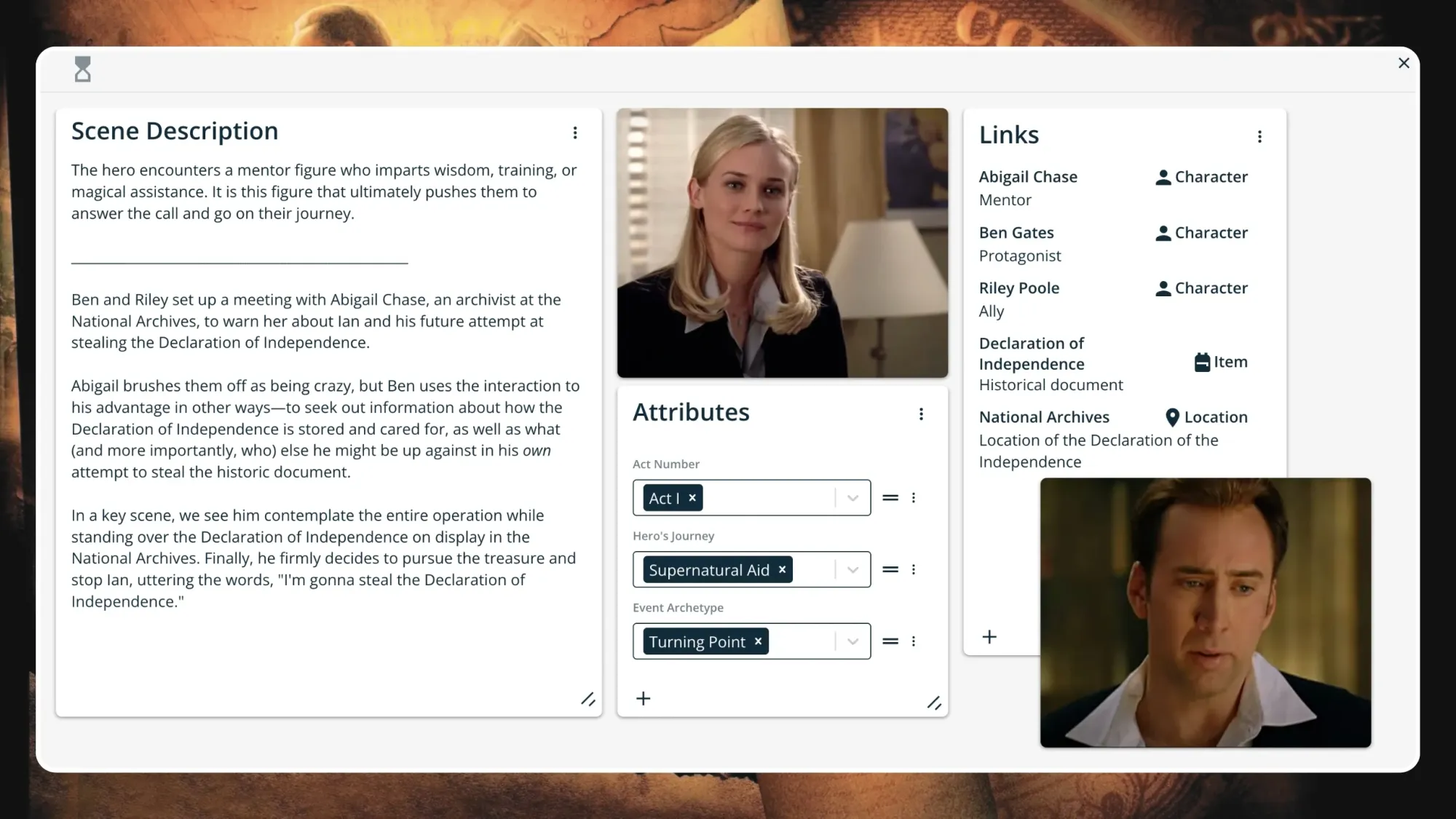

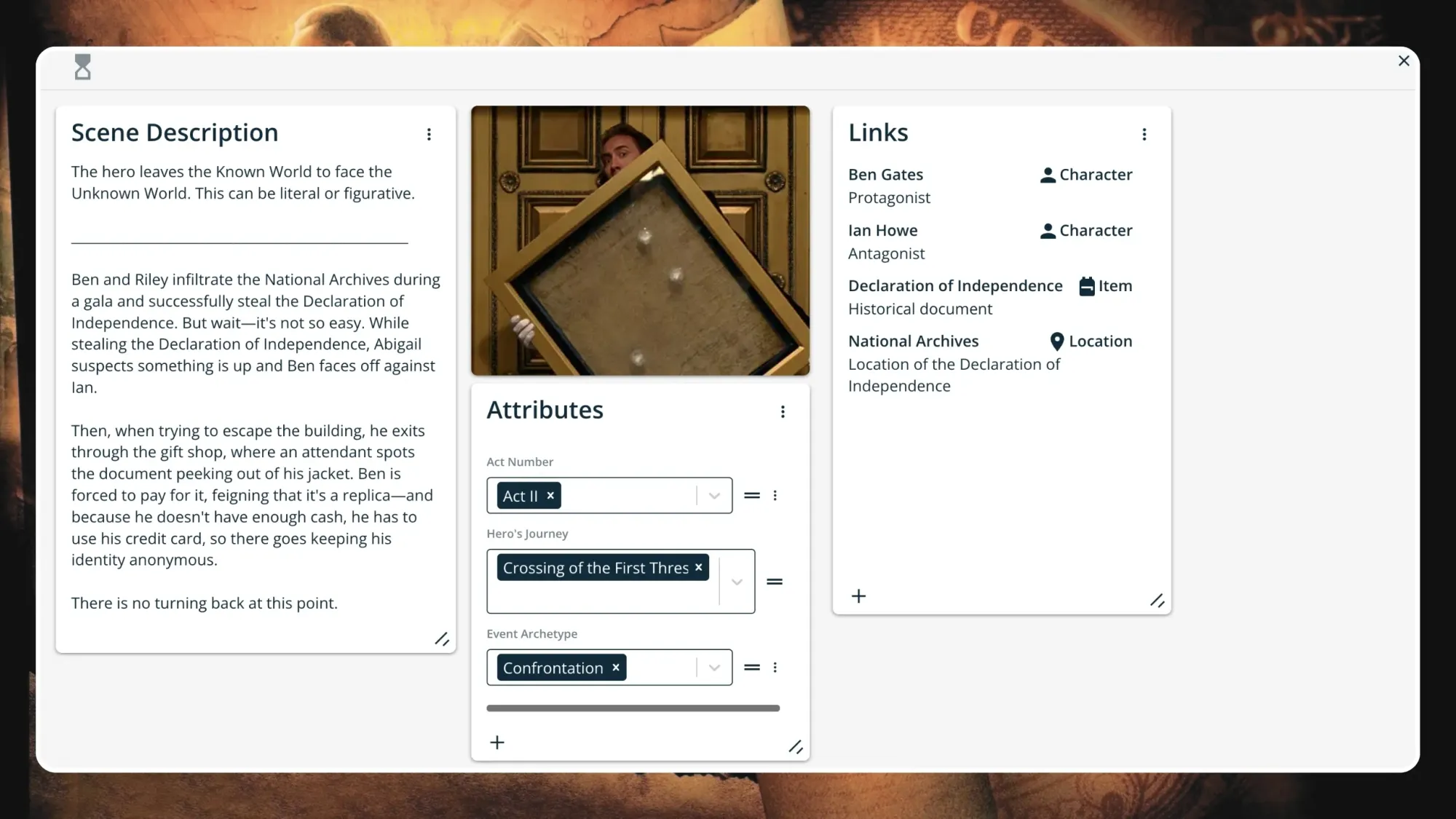

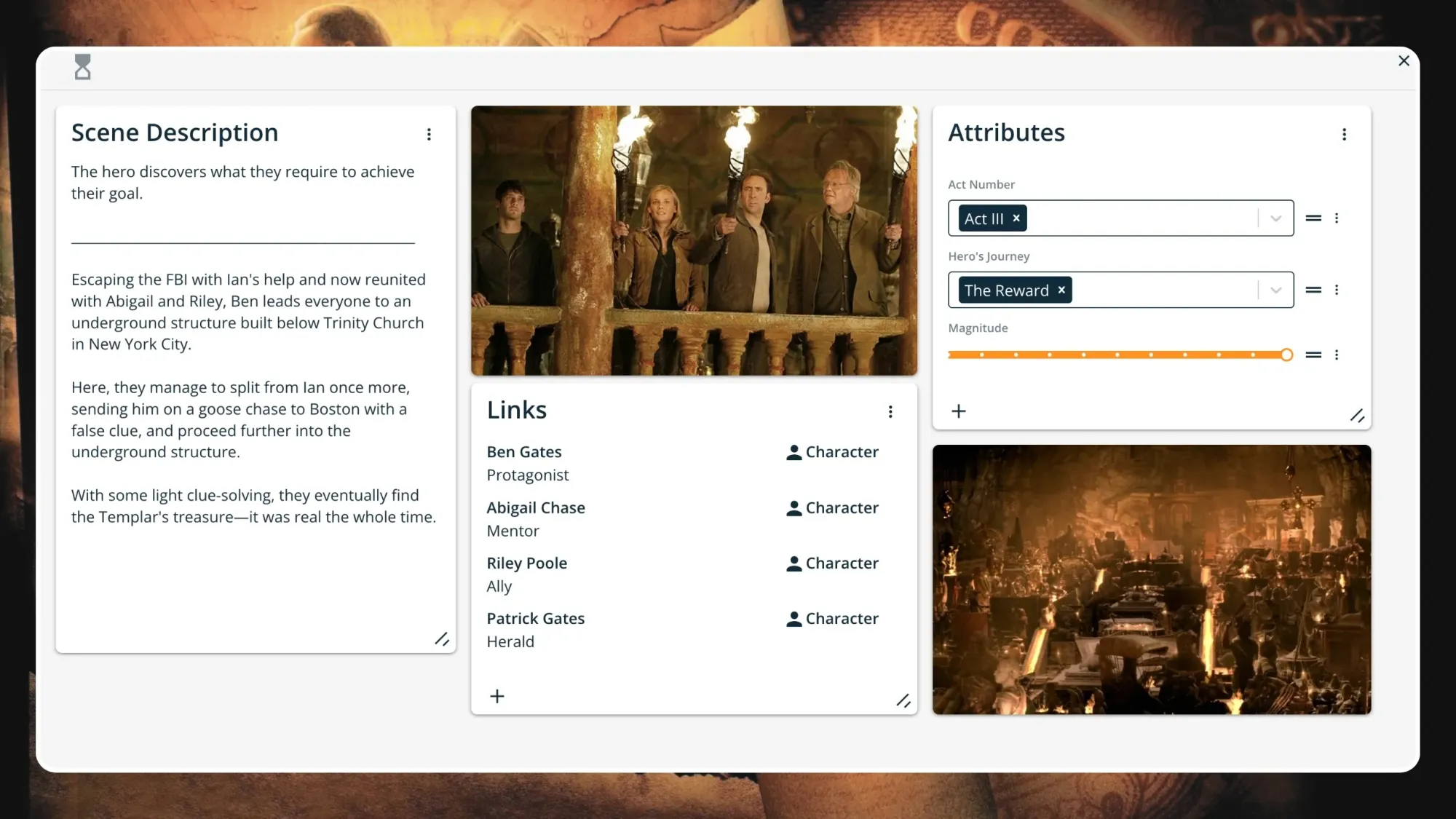

With the help of his main ally, Riley, and a crew of other treasure hunters backed by a wealthy patron, he finds an 18th-century American ship in the Canadian Arctic, the Charlotte . Here, they find a ship-shaped pipe that presents a new riddle and later doubles as a key—for now, it's just another clue in the search for the lost treasure of the Templars, one that leads them to the Declaration of Independence.

Step 2. The Call to Adventure

The inciting incident takes place and the hero is called to act upon it. While they're still firmly in the Known World, the story kicks off and leaves the hero feeling out of balance. In other words, they are placed at a crossroads.

Ian (the wealthy patron of the Charlotte operation) steals the pipe from Ben and Riley and leaves them stranded. This is a key moment: Ian becomes the villain, Ben has now sufficiently lost his funding for this expedition, and if he decides to pursue the chase, he'll be up against extreme odds.

Step 3. Refusal of the Call

The hero hesitates and instead refuses their call to action. Following the call would mean making a conscious decision to break away from the status quo. Ahead lies danger, risk, and the unknown; but here and now, the hero is still in the safety and comfort of what they know.