- Skip to primary navigation

- Skip to main content

- Skip to primary sidebar

- Skip to footer

TravelAwaits

Our mission is to serve the 50+ traveler who's ready to cross a few items off their bucket list.

18 Beautiful Coastal Towns To Visit Around The World

- Destinations

From cobblestone streets to white sand beaches, small coastal towns harness a charm unmatched by popular tourist destinations. Something about quaint atmospheres and untouched coastlines gives you a feeling you must be the only person in the world to discover these little pieces of paradise. Luckily, there are many all over the globe offering a taste of authentic culture with a side of luxury. Let’s explore 18 of these beautiful coastal towns you must visit around the world.

1. Loreto, Mexico

To get that authentic taste of Mexico, Loreto is the perfect small town. Located about 300 miles north of Cabo San Lucas, this coastal town is quiet, quaint, and relaxed. The charm of this area can be found in cobblestone streets, family-style restaurants, and the historical downtown. The Loreto National Marine Park is one of Mexico’s most important reserves with more than 800 species of fish and marine life. To explore, take a guided hike which will give you breathtaking views of the Sea of Cortez and the jagged rock formations that rise out of it. If you visit in January or March, take a whale-watching tour to get a glimpse of humpback and blue whales that migrate down the Baja peninsula.

2. Sayulita, Mexico

The village of Sayulita on the Pacific coast of Mexico is known for its fishing and world-class surfing. An hour’s drive from Puerto Vallarta, this coastal town has a laid-back beach vibe with tons of culture and character. The cobblestone streets are lined with art galleries, local shops, and unique restaurants. The waters off the beaches are filled with surfers from all levels from beginners to pros. You can find many surf schools that offer lessons. Huichol art is also popular in Sayulita. The Huichol, one of four Indigenous peoples in the Riviera Nayarit, are direct descendants of the Aztecs. You can find unique pieces of art which tell a historic or mythical story.

Read our picks for the best hotels in Sayulita.

3. Placencia, Belize

This beach town on the Caribbean coast of Belize has 16 miles of beaches. Placencia is one of the most popular destinations in Belize for those looking for a coastal town. It has everything from fishing to water activities to Mayan ruins and tropical jungles. Go kayaking, fly fishing, snorkeling, or scuba diving with white sharks. There are also luxury beach resorts, world-class restaurants, and fun beach bars. But all that hasn’t impacted its quaint feeling. Quiet restaurants with tables in the sand serve lobster, a staple in the area. One highlight is to visit the Turtle Inn, owned by Francis Ford Coppola, so while you dine you can also enjoy an extensive collection of Coppola wines.

4. Tamarindo, Costa Rica

The popular beach town of Tamarindo is located in Guanacaste Province, on Costa Rica’s Pacific coast. It’s the spot for surfing, sport fishing, scuba diving, and basking in the sun. Get out and explore the area in some thrilling activities like sailing, snorkeling, volcano hiking, and zip lining. All of which you can do on a guided tour. If you visit between October and March, there are also guided tours of turtle nests. Las Baulas National Marine Park is the largest nesting ground in the world for endangered leatherback turtles. Restaurants in Tamarindo serve tacos, burritos, and beans and rice with chicken or shrimp.

10 Costa Rica Vacation Rentals For Your Next Tropical Trip

5. Paracas, Peru

Located on Peru’s West Coast, Paracas is known for its beaches. While enjoying the sand and crystal waters, you can spot sea lions, pelicans, and Humboldt penguins, all of which call this town home. Tours will get you up close and personal with these incredible creatures in their natural habitats. A unique experience is a massive candlestick carved into the side of a bluff called Paracas Candelabra. No one knows how this relic of an ancient civilization got there or why. A favorite dish is a ceviche since the seafood is so fresh and don’t miss the chance to drink authentic Peruvian pisco at a local vineyard, or any restaurant since it’s so popular.

6. Estoril, Portugal

Just 40 minutes from Lisbon, Portugal, is the beach town of Estoril . Once a destination for royalty and celebrities, this quiet town is perfect for a getaway. The soft, sand beaches allow for some sunbathing or grabbing a meal and a drink at one of the restaurants which line it. Sports fans will enjoy visiting to catch a car race, tennis match, or fútbol match. Of course, we have to mention James Bond. Ian Fleming, the creator of the character, came up with 007 while he was staying at the Estoril Palacio Hotel. James Bond and the first book, Casino Royale were inspired by the environment and spies he met there. Additionally, portions of the film, On Her Majesty’s Secret Service, were filmed here.

7. Plymouth, England

Plymouth is a port city in southwest England known for its maritime heritage and charming cobblestone streets. The city is more famously known though for being the location where the Mayflower departed in 1620 with 102 pilgrims onboard headed for America. A trip to Smeaton’s Tower will give you a glimpse of the town’s past photos. Visit the National Marine Aquarium and see more than 5,000 ocean animals including sharks and rays. Take a tour of the Plymouth Gin Distillery and taste gin from England’s oldest working distillery, established in 1793. While it’s a coastal town, you can also explore the countryside or do some antique shopping through many of the town’s shops.

8. Portofino, Italy

The fishing village of Portofino is located on the Italian Riviera. It’s one of the most popular resort towns visited by the rich and famous but still holds its charm as a fishing village. It’s known for its unique pastel-colored buildings that line the shore of the harbor that’s filled with yachts and fishing boats. Get a taste of the area’s history through a visit to Brown’s Castle and San Martino Church. Scuba divers get the rare chance to dive 56 feet down to see Christ of the Abyss , an 8-foot-tall bronze statue placed there in 1950 in memory of Italy’s first scuba diver who died there. There are also plenty of amazing restaurants and elegant shops for those who prefer to stay on shore.

9. Sidi Bou Said, Tunisia

Cobblestone streets and blue-and-white houses make the town of Sidi Bou Said in Tunisia unforgettable. The African town sits high on a cliff and overlooks the Mediterranean. Along the streets, you’ll find al fresco cafés, art galleries, and local shops. A favorite spot to see the view of the Gulf of Tunis is from the lighthouse. There aren’t many hotels to choose from, but one of the most popular is La Villa Bleue, which has just 13 rooms, a gourmet restaurant, a swimming pool with a sea view, and a spa. Reserve your place early!

10. Nafplio, Greece

The coastal Grecian city of Nafplio is one of the most romantic cities in the country. Located on the Peloponnese on the shore of the Argolic Gulf, this town was the capital of Greece until 1834. It’s rich in history and according to mythology, was founded by Nafplios, the son of Poseidon and the daughter of Danaus Anymone. Visit three castles located in the area: Akronafplia Castle, Bourtzi Castle, and Palamidi Castle. The Arvanitia Promenade is a popular walk to see the sunset or take a tourist train to see sites and local souvenir shops.

11. Amasra, Turkiye (Turkey)

The small Black Sea coastal town of Amasra is an easy one to explore. Located on a promontory and formed by two islands, this ancient town is steeped in Roman and Byzantine history with stunning views of the sea. What also makes it unique is how it is untouched by tourism. Some important spots to visit include the castle with an underground tunnel that leads to a freshwater pool, the archaeological museum, and the Bird’s Rock Road Monument, carved into the rock between 41-54 A.D. A must-try are Black Sea anchovies, called hamsi . From Amasra, enjoy all that the Black Sea Coast of Turkiye has to offer.

12. Michamvi, Tanzania

The small fishing village of Michamvi, Tanzania , is located on the southeastern coast of Zanzibar. White sand beaches and clear blue waters make this location magical for those looking for a peaceful getaway. You can watch the sunrise over the Indian Ocean and see it set over Chwaka Bay. The fringe reef is popular with divers and snorkelers alike looking for marine life. Thrill-seekers will find world-class kite surfing, kayaking, paddle boarding, and surfing. There are plenty of luxurious beach resorts and hideaway stays.

13. Prachuap Khiri Khan, Thailand

Four hours south of Bangkok sits the fishing village of Prachuap Khiri Khan, Thailand . The main attraction is the temple on top of the hill at the center of town. You’ll also want to visit the iconic large Buddha. Along the waterfront at night is a market with souvenirs and local cuisine. You’ll go through the military base to get to the beach where you can stroll, rent a chair, and grab some food. There is a colony of monkeys located here. Inside Wing 5, they are friendly and calm. But beware of the other species by the more aggressive temple, and, if you’re not careful, may rob you!

14. Hoi An, Vietnam

The well-preserved ancient town of Hoi An is on Vietnam’s Central Coast. Enjoy a relaxing afternoon at An Bang Beach or a bike tour of the countryside where you can see views of the sea buffalo in their natural habitat, vegetable farms, and lovely ponds. Stroll along the cobblestone streets of Old Town, classified as a UNESCO World Heritage Site, with 21 historical sites to visit. You can also visit local boutiques, coffee shops, and restaurants. Three dishes to try in Hoi An are Cao Lau, Hoanh Thanh, and white rose dumplings. Take a walk across the Japanese Bridge built in the 1590s.

15. Byron Bay, Australia

This popular holiday destination is known for its beaches, surfing, and scuba diving. Byron Bay, Australia , has no high rises and plenty of national parks. It’s home to the iconic Cape Byron lighthouse, which sits at the country’s easternmost point, creating incredible views. There’s a comfortable contrast between its alternative culture and hippie lifestyle, award-winning restaurants, luxurious hotels, and beach houses, as well as craft breweries. You can spend the day on the white sand beaches doing yoga, sunbathing, or exploring the tropical rainforests or farmlands. If you visit between May and November, take a whale-watching tour to see the migrating humpback whales.

16. Lakes Entrance, Australia

Known for its Gippsland Lakes, Lakes Entrance, Australia , is a coastal town in Victoria. It’s home to one of the longest and most unspoiled beaches on Earth: Ninety Mile Beach. There is plenty to do outdoors. Surf the waters, kayak the lakes, take a paddleboat, or do some beach camping. Keep your eyes peeled for wildlife like kangaroos, pelicans, and dolphins along the beaches. Lakes Entrance is renowned as a seafood capital because it’s a fishing town. You can try it at a local restaurant or catch your own. Check out the Griffiths Sea Shell Museum to learn about local marine life and coral reefs.

17. Russell, New Zealand

The charming town of Russell, New Zealand , is located in the Bay of Islands on the North Island. It was the country’s first seaport and first European settlement, so it is rich in history. The town’s streets still have the original layout and names from 1843. You can also visit many of the historic buildings. Spend some time at The Russell Museum to learn about Maori culture. If you’re up for some adventure, you’ll want to take in the views from a parasail in Russell. Plan to spend an afternoon at Oneroa Bay, one of the best beaches in the bay. The waves are perfect for swimming, boogie boarding, or surfing.

18. Napier, New Zealand

The coastal city of Napier sits on New Zealand’s North Island and is a renowned wine-producing region. So you’ll want to visit some wineries and vineyards on your trip. For art lovers, Napier is famous for having one of the most complete collections of Art Deco buildings in the world. If you visit in February, you can take part in the Art Deco Festival, which celebrates 1930s vintage cars, fashion, and music.

Bike, walk, or run the popular Napier Walkway which goes right through the city center and for miles in both directions right along the sea. The Marine Parade takes you by the Pania of the Reef statue depicting a Maori maiden, a symbol of the city. Enjoy fantastic restaurants, quaint cafés, fun bars, and boutique shops.

To read other articles about coastal towns, check out:

- 16 Amazing U.S. Beach Towns That Top Our Readers’ Travel Lists (2023)

- 7 Quick Facts About Piran, Slovenia’s Beautiful Coastal Town

- The Unique Ways To Experience The Coastal Vineyards Of South Australia

Allison spent almost 20 years of her career as a TV news anchor. She’s covered everything from political conventions to Super Bowl LV to hurricanes and, most recently, the pandemic. She is a two-time Emmy award-winning journalist. She's been recognized for her work nationally and regionally by organizations including the Associated Press, the Society of Professional Journalists, and the Florida Association of Broadcast Journalists.

- Show search

Perspectives

How Tourism Can Be Good for Coral Reefs

Data highlights opportunities for the tourism industry to support better conservation outcomes

April 25, 2017

View The Study

Coral reefs could be considered the poster child of nature-based tourism. People come specifically to visit the reefs themselves, to swim over shimmering gardens of coral amongst hordes of fish. But even if you aren’t snorkeling or diving on a reef, your tropical beach vacation was likely made possible by a coral reef.

The world’s coral reefs perform many essential roles. They are home to the fish that provide the food - and often livelihoods - for nearly 100 million people. They also act as barriers against the worst impacts of storms, protecting the beaches and the millions of people who live around and rely upon them. By modelling the economic contributions of coral reefs to global and local economies, this work can be used to persuade governments of the importance of investing in their protection.

Quote : Source: Mapping Ocean Wealth

The global economic value of coral reefs for tourism is $36 billion/year

Source: Mapping Ocean Wealth

In a study published in the Journal of Marine Policy , The Nature Conservancy’s Mapping Ocean Wealth (MOW) initiative and partners, used an innovative combination of data-driven academic research and crowd-sourced and social media-related data to reveal that 70 million trips are supported by the world’s coral reefs each year, making these reefs a powerful engine for tourism.

In total, coral reefs represent an astonishing $36 billion a year in economic value to the world. Of that $36 billion, $19 billion represents actual “on-reef” tourism like diving, snorkeling, glass-bottom boating and wildlife watching on reefs themselves. The other $16 billion comes from “reef-adjacent” tourism, which encompasses everything from enjoying beautiful views and beaches, to local seafood, paddleboarding and other activities that are afforded by the sheltering effect of adjacent reefs.

There are more than 70 countries across the world that generate more than 1 million dollars per square mile.

In fact, there are more than 70 countries and territories across the world that have million dollar reefs—reefs that generate more than one million dollars per square kilometer. These reefs support businesses and people in the Florida Keys, Bahamas, Mexico, Indonesia, Australia, and Mauritius, to name a few. Demonstrating this value creates a powerful incentive for local businesses and governments to preserve these essential ecosystems.

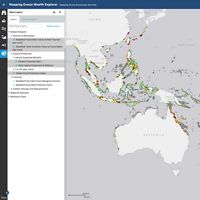

The Conservancy’s Atlas of Ocean Wealth , and the accompanying interactive mapping tool , serves as a valuable resource for managers and decision makers to drill down to determine not just the location of coral reefs or other important natural assets, but how much they’re worth, in terms of their economic value as well as fish production, carbon storage and coastal protection values. By revealing where benefits are produced and at what level, the MOW maps and tools can help businesses fully understand and make new investments in protecting the natural systems that underpin their businesses.

The Methodology

Along with traditional data-driven academic research, and research from the emerging fields of crowd-sourced and social media-related data, a combination of tourism datasets that included hotel rooms, general photographs, underwater photographs, dive centers and dive site were used to render and improve crude national statistics, and also to cross-validate with independent datasets – for example, using hotel locations alongside number of photos taken in a location to independently show tourism spread at national levels, and using dive-sites and locations of underwater photographs to distinguish between tourism activities that take place directly on the reef (e.g., snorkeling, diving) versus tourism activities that indirectly benefit from the presence of coral reefs (e.g., enjoying pristine beaches, calm waters, and fresh seafood).

The data is available in the mapping application , which allows users to view and compare economic and visitation values of coral reef tourism around the world. Users can also focus on specific geographies, such as Florida, the Bahamas, the Eastern Caribbean, and Micronesia, to view a more fine-scale distribution of values in these regions.

Armed with concrete information about the value of these important natural assets, the tourism industry can start to make more informed decisions about the management and conservation of the reefs they depend on—and thus become powerful allies in the conservation movement.

The concept of valuing nature isn’t a new one, but the detailed, targeted knowledge of the MOW initiative presents an opportunity for the travel and tourism industry to lead both in the private sector, institutionalizing the value of nature into business practices and corporate sustainability investments, and in the sustainability movement more broadly by capturing the business opportunities that exist when we realize that we need nature.

Quote : Dr. Robert Brumbaugh

It’s clear that the tourism industry depends on coral reefs. But now, more than ever, coral reefs are depending on the tourism industry."

Dr. Robert Brumbaugh

For those interested in learning more, or if you have questions or feedback, contact us at [email protected] .

Atlas of Ocean Wealth

This Atlas represents the largest collection to date of the economic, social and cultural values of coastal and marine habitats globally. View Atlas

Mapping Ocean Wealth

Understanding in quantitative terms all that the ocean does for us today, so that we make smarter investments and decisions for the ocean of tomorrow. Visit Site

Recreation and Tourism Data Portal

Dig in to visualize and simplify global, regional and local ecosystem benefits for use in natural resource planning and policy decisions. Explore the Data

Related Reading

Insuring Nature to Ensure a Resilient Future

Integrated solutions linking nature and insurance can help to reduce risk and build resilience to the impacts of climate change.

It's Not Too Late to Save Coral Reefs

Coral reefs are imperiled worldwide, but engaging new sectors in conservation could help us save these vital ecosystems.

By Mark Spalding

Could Insuring Mangroves Save Them—and Protect Coastal Communities?

New research demonstrates the feasibility of mangrove insurance projects in the Gulf of Mexico and the Caribbean, as well as identifying the most cost-effective locations to start.

Global Insights

Check out our latest thinking and real-world solutions to some of the most complex challenges facing people and the planet today.

We personalize nature.org for you

This website uses cookies to enhance your experience and analyze performance and traffic on our website.

To manage or opt-out of receiving cookies, please visit our

- View source

- View history

- Community portal

- Recent changes

- Random page

- Featured content

- What links here

- Related changes

- Special pages

- Printable version

- Permanent link

- Page information

- Browse properties

Impact of tourism in coastal areas: Need of sustainable tourism strategy

This article discusses the current status of coastal tourism , the associated issues and impacts. The article further provides recommendations for future management of coastal tourism.

- 1 Introduction

- 2.1 Causes of coastal degradation

- 3.1 Tourist infrastructure

- 3.2 Careless resorts, operators, and tourists

- 5.1 Environmental impacts

- 5.2 Impacts on biodiversity

- 5.3 Socio-cultural impacts

- 6.1 Economic benefits

- 6.2 Environmental Management and Planning benefits

- 6.3 Socio-cultural benefits

- 7.1 Analysis of status-quo

- 7.2 Strategy development

- 7.3 Action plan

- 8 Conclusions

- 9.1 External links

- 9.2 Internal Links

- 10 References

Introduction

Since the 1992 Earth Summit in Rio de Janeiro, there is increasing awareness of the importance of sustainable forms of tourism. Although tourism , one of the world largest industries, was not the subject of a chapter in Agenda 21 , the Programme for the further implementation of Agenda 21, adopted by the General Assembly at its nineteenth special session in 1997, included sustainable tourism as one of its sectoral themes. Furthermore in 1996, The World Tourism Organization jointly with the tourism private sector issued an Agenda 21 for the Travel and Tourism Industry, with 19 specific areas of action recommended to governments and private operators towards sustainability in tourism.

On the other hand, an analysis of the sustainability policies, strategies and instruments of 21 European countries revealed a gap between good theoretical approaches and the general willingness to support a sustainable tourism development and the realisation of it, and concluded that in hardly any of the countries is sustainable tourism put in the centre of the national tourism policy as a priority area [1] .

Specific situation of coastal areas

Coastal areas are transitional areas between the land and sea characterized by a very high biodiversity. They include some of the richest and most fragile ecosystems on earth, like mangroves and coral reefs . At the same time, coasts are under very high population pressure due to rapid urbanization processes. More than half of today’s world population live in coastal areas (within 60 km from the sea) and this number is on the rise.

Additionally, among all different parts of the planet, coastal areas are those which are most visited by tourists and in many coastal areas tourism presents the most important economic activity. In the Mediterranean region for example, tourism is the first economic activity for islands like Cyprus, Malta, the Balearic Islands and Sicily.

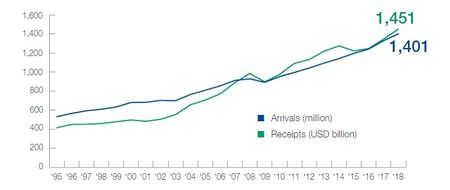

Forecast studies carried out by WTO in 2000 estimated that international tourist arrivals to the Mediterranean coast would amount to 270 millions in 2010 and to 346 millions in 2020. However, the latter figure was reached already in 2015 [2] .

Causes of coastal degradation

Tourisms often contributes to coastal degradation. There are many other causes:

- Coastal zone urbanization

- Fisheries and aquaculture

- Port development and shipping

- Land reclamation

- Land-use conversion (Agriculture, Industrial development)

- Climate change and sea level rise

See also Threats to the coastal zone .

How does tourism damage coastal environment

Massive influxes of tourists, often to a relatively small area, have a huge impact. They add to the pollution, waste, and water needs of the local population, putting local infrastructure and habitats under enormous pressure. For example, 85% of the 1.8 million people who visit Australia's Great Barrier Reef are concentrated in two small areas, Cairns and the Whitsunday Islands, which together have a human population of about 130,000.

Tourist infrastructure

In many areas, massive new tourist infrastructure has been built - including airports, marinas, resorts, and golf courses. Overdevelopment for tourism has the same problems as other coastal developments, but often has a greater impact as the tourist developments are located at or near fragile marine ecosystems . A few examples:

- mangrove forests and seagrass meadows have been removed to create open beaches;

- tourist developments such as piers and other structures have been built directly on top of coral reefs ;

- nesting sites for endangered marine turtles have been destroyed and disturbed by large numbers of tourists on the beaches.

Careless resorts, operators, and tourists

The damage is not only due to the construction of tourist infrastructure. Some tourist resorts empty their sewage and other wastes directly into water surrounding coral reefs and other sensitive marine habitats . Recreational activities also have a strong impact. For example, careless boating, diving, snorkeling, and fishing have substantially damaged coral reefs in many parts of the world, through people touching reefs, stirring up sediment , and dropping anchors. Marine animals such as whale sharks, seals, dugongs, dolphins, whales, and birds are also disturbed by increased numbers of boats, and by people approaching too closely. Tourism can also add to the consumption of seafood in an area, putting pressure on local fish populations and sometimes contributing to overfishing. Collection of corals, shells, and other marine souvenirs - either by individual tourists, or local people who then sell the souvenirs to tourists - also has a detrimental effect on the local environment.

The case of cruise ship tourism

Cruise ship tourism is a fast growing sector of the tourism industry during the past decades. While world international tourist arrivals in the period 1990 – 1999 grew at an accumulative annual rate of 4.2%, that of cruises did by 7.7%. In 1990 there were 4.5 million international cruise arrivals which had increased to a number of 8.7 million in 1999 and to 27 million in 2019, with gross economic benefits estimated at $150 billion in direct, indirect and induced economic benefits [3] [4] . From the 1980s to 2018, the global cruise fleet grew from 79 to 369 vessels operating worldwide, and the average cruise ship size and capacity grew from 19.000 to 60.000 gross registered tonnage (GRT). Carrying on average 4,000 passengers and 1,670 crew, these enormous floating towns are a major source of marine pollution through the dumping of garbage and untreated sewage at sea, and the release of other shipping-related pollutants.

Problems caused by cruise tourism are ubiquitous and well-documented, especially for small island nations and the Mediterranean [5] [6] .

- Discharge of sewage in marinas and nearshore coastal areas . The lack of adequate port reception facilities for solid waste, especially in many small islands, as well as the frequent lack of garbage storing facilities on board can result in solid wastes being disposed of at sea, and being transported by wind and currents to shore often in locations distant from the original source of the material.

- Coral reefs. Land-based activities such as port development and the dredging that inevitably accompanies it in order to receive cruise ships with sometimes more than 3000 passengers can significantly degrade coral reefs through the build-up of sediment . Furthermore, sand mining at the beaches leads to coastal erosion . In the Cayman Islands damage has been done by cruise ships dropping anchor on the reefs. Scientists have acknowledged that more than 300 acres of coral reef have already been lost to cruise ship anchors in the harbour at George Town, the capital of Grand Cayman.

- Socio-cultural impacts. Cruise-ship tourism can produce socio-cultural stress, since it means that during very short periods there is high influx of people, sometimes more than the local inhabitants of small islands, possibly overrunning local communities. Vital resources such as food, energy, land, water, etc. may become depleted.

- Ship emissions. Fuel-based cruise ships currently produce large amounts of greenhouse gases. The gradual replacement is only now starting. From the approximately 100 new builds planned up to 2027, one-fifth are LNG powered, corresponding to 39% of the new tonnage and 41% of the added capacity [7] .

Cruise tourism is often ascribed as hedonistic. However, a positive effect of expedition cruise tourism is its educational and awareness-creation potential for sustainability values and issues. It can transform a ‘sense of place’ to a ‘care of place’, encouraging tourists and locals to assume more responsibility [8] .

Impacts of coastal tourism

Environmental impacts

- The intensive use of land by tourism and leisure facilities

- Overuse of water resources, especially groundwater, leading to soil subsidence and saline intrusion

- Changes in the landscape due to the construction of infrastructure, buildings and facilities

- Vulnerability to natural hazards and sea level rise

- Pollution of marine and freshwater resources

- Energy demand and consumption

- Air pollution and waste

- Disturbance of fauna and local people (for example, by noise)

- Loss of marine resources due to destruction of coral reefs , overfishing

- Compaction and sealing of soils, soil degradation due to overuse of fertilizers and loss of land resources (e.g. desertification , erosion )

- Loss of public access

Impacts on biodiversity

Tourism can cause loss of biodiversity in many ways, e.g. by competing with wildlife for habitat and natural resources or by providing pathways for the introduction of alien species. Negative impacts on biodiversity are caused by various other factors, such as those mentioned above.

Socio-cultural impacts

Change of local identity and values:

- Commercialization of local culture: Tourism can turn local culture into commodities when religious traditions, local customs and festivals are reduced to conform to tourist expectations and resulting in what has been called "reconstructed ethnicity".

- Standardization: Destinations risk standardization in the process of tourists desires and satisfaction: while landscape, accommodation, food and drinks, etc., must meet the tourists expectation for the new and unfamiliar situation. They must at the same time not be too new or strange because few tourists are actually looking for completely new things. This factor damages the variation and beauty of diverse cultures.

- Adaptation to tourist demands: Tourists want to collect souvenirs, arts, crafts, cultural manifestations. In many tourist destinations, craftsmen have responded to the growing demand and have made changes in the design of their products to make them more attractive to the new customers. Cultural erosion may occur in the process of commercializing cultural traditions.

Cultural clashes may arise through:

- Economic inequality - between locals and tourists who are spending more than they usually do at home.

- Irritation due to tourist behaviour - Tourists often, out of ignorance or carelessness, fail to respect local customs and moral values.

- Job level friction - due to a lack of professional training, many low-paid tourism-jobs go to local people while higher-paying and more prestigious managerial jobs go to foreigners or "urbanized" nationals.

Benefits of Sustainable coastal tourism

Economic benefits.

The main positive economic impacts of sustainable (coastal) tourism are: contributions to government revenues, foreign exchange earnings, generation of employment and business opportunities. Employing over 3.2 million people, coastal tourism generates a total of € 183 billion in gross value added and represents over one third of the maritime economy of the European Union. As much as 51% of bed capacity in hotels across Europe is concentrated in regions with a sea border [10] .

Contribution to government revenues Government revenues from the tourism sector can be categorised as direct and indirect contributions. Direct contributions are generated by income taxes from tourism and employment due to tourism, tourism businesses and by direct charges on tourists such as ecotax. Indirect contributions derive from taxes and duties on goods and services supplied to tourists, for example, taxes on tickets (or entry passes to any protected areas), souvenirs, alcohol, restaurants, hotels, service of tour operators.

Foreign exchange earnings Tourism expenditures, the export and import of related goods and services generate income to the host economy. Tourism is a main source of foreign exchange earnings for at least 38 % of all countries.

Employment generation The rapid expansion of international tourism has led to significant employment creation. Tourism can generate jobs directly through hotels, restaurants, taxis, souvenir sales and indirectly through the supply of goods and services needed by tourism-related businesses (e.g. conducted tour operators). Tourism represents around 7 % of the world’s employees. Tourism can influence the local government to improve the infrastructure by creating better water and sewage systems, roads, electricity, telephone and public transport networks. All this can improve the standard of living for residents as well as facilitate tourism.

Contribution to local economies Tourism can be a significant or even an essential part of the local economy. As environment is a basic component of the tourism industry’s assets, tourism revenues are often used to measure the economic value of protected areas. Part of the tourism income comes from informal employment, such as street vendors and informal guides. The positive side of informal or unreported employment is that the money is returned to the local economy and has a great multiplier effect as it is spent over and over again. The Global Sustainable Tourism Council (GSTC) estimates that tourism generates an indirect contribution equal to 100 % of direct tourism expenditures.

Direct financial contributions to nature protection Tourism can contribute directly to the conservation of sensitive areas and habitats . Revenue from park-entrance fees and similar sources can be allocated specifically to pay for the protection and management of environmentally sensitive areas. Some governments collect money in more far-reaching and indirect ways that are not linked to specific parks or conservation areas. User fees, income taxes, taxes on sales or rental of recreation equipment and license fees for activities such as hunting and fishing can provide governments with the funds needed to manage natural resources.

Competitive advantage More and more tour operators take an active approach towards sustainability. Not only because consumers expect them to do so but also because they are aware that intact destinations are essential for the long term survival of the tourism industry. More and more tour operators prefer to work with suppliers who act in a sustainable manner, e.g. saving water and energy, respecting the local culture and supporting the well-being of local communities. In 2000 the international Tour Operators initiative for Sustainable Tourism was founded with the support of UNEP. In 2014 it merged with the Global Sustainable Tourism Council (GSTC) .

Environmental Management and Planning benefits

Sound and efficient environmental management of tourism facilities and especially hotels (e.g.water and energy saving measures, waste minimization, use of environmentally friendly material) can decrease the environmental impact of tourism. Planning helps to make choices between the conflicting interests of industry and tourism, in order to find ways to make them compatible. Planning sustainable tourism development strategy at an early stage prevents damages and expensive mistakes, thereby avoiding the gradual deterioration of the quality of environmental goods and services significant to tourism.

Socio-cultural benefits

Tourism as a force for peace Travelling brings people into contact with each other. As sustainable tourism has an educational element it can foster understanding between people and cultures and provide cultural exchange between guests and hosts. This increases the chances for people to develop mutual sympathy, tolerance and understanding and to reduce prejudices and promote the sense of global brotherhood.

Strengthening communities Sustainable Coastal Tourism can add to the vitality of communities in many ways. For example through events and festivals of the local communities where they have been the primary participants and spectators. Often these are refreshed, reincarnated and developed in response to tourists’ interests. The jobs created by tourism can act as a very important motivation to reduce emigration from rural areas. Local people can also increase their influence on tourism development, as well as improve their jobs and earnings prospects through tourism-related professional training and development of business and organizational skills.

Revitalization of culture and traditions Sustainable Tourism can also improve the preservation and transmission of cultural and historical traditions . Contributing to the conservation and sustainable management of natural resources can bring opportunities to protect local heritage or to revitalize native cultures, for instance by regenerating traditional arts and crafts.

Encouragement social involvement and pride In some situations, tourism also helps to raise local awareness concerning the financial value of natural and cultural sites. It can stimulate a feeling of pride in local and national heritage and interest in its conservation. More broadly, the involvement of local communities in sustainable tourism development and operation seems to be an important condition for the sustainable use and conservation of the biodiversity .

Benefits for the tourists of Sustainable Tourism The benefits of sustainable tourism for visitors are plenty: they can enjoy unspoiled nature and landscapes, environmental quality of goods or services (clean air and water), a healthy community with low crime rate, thriving and authentic local culture and traditions.

Sustainable Tourism Strategy

The sustainable management of tourism is a complex managerial undertaking, requiring the involvement of multiple stakeholder groups, at local, regional and international levels. It entails a large set of actors and stakeholders, ranging from tour operators, industry associations and NGOs to local public authorities, businesses and independent small vendors. Indirectly, ‘producing holiday experiences’ involves entire communities and is subject to a multiplicity of motives, interests and perspectives [7] . In other words, the tourism economy consists of an entire network of institutional and business actors, that should be engaged in sustainable practices through rules and incentives.

Below a few steps are listed for the development and implementation of a strategy for sustainable tourism.

Analysis of status-quo

- Analysis of previous tourism management strategies for the specific area: What can be used? Has it been implemented? Which lessons are to be learnt?

- A stakeholder analysis: Who has an interest in sustainable tourism development? Who are the main actors?

- Facts and figures of the local educational system, economic and social structure

- Anecdotal and traditional knowledge

This information can be collected through

- Interviews with stakeholders

- Questionnaires distributed and collected by e-mail, fax or personally in order to compile standardised data and perform a statistical analysis

- Participation in focus group meetings (e.g. meetings on environmental education, biodiversity management, good governance and fisheries)

- Literature search (including the local library)

Strategy development

A Sustainable Tourism Strategy is based on the information collected. It defines the priority issues, the stakeholder community, the potential objectives and a set of methodologies to reach these objectives. These include:

- Conservation of specific coastal landscapes or habitats that make the area attractive or protected under nature conservation legislation

- Development of regionally specific sectors of the economy that can be interlinked with the tourism sector (e.g. production of food specialities and handicrafts)

- Maximising local revenues from tourism investments

- Enabling self-determined cultural development in the region, etc.

Action plan

The Action Plan describes the steps needed to implement the strategy and addresses a number of practical questions such as: which organizations will take up which activities, over what time frame, by what means and with which resources? As the actions have to be considered on the basis of regional circumstances, there is no standard action plan for all. However, Action Plans usually include measures in the following fields:

- Administration: e.g. promotion of co-operation between sectors and of cross-sectorial development models; involving local people in drafting tourism policy and decisions

- Socio-economical sector: e.g. promoting local purchasing of food and building material; setting up networks of local producers for better marketing; development of new products to meet the needs of tourists, etc.

- Environment: e.g. improving control and enforcement of environmental standards (noise, drinking water, bathing water, waste-water treatment, etc.); identification and protection of endangered habitats; creation of buffer zones around sensitive natural areas; prohibition of environmentally harmful sports in jeopardised regions; strict application of Environmental Impact Assessment (EIA) and Strategic Environmental Assessment procedures on all tourism related projects and programs

- Knowledge: training people involved in coastal tourism about the value of historical heritage; environmental management; training protected area management staff in nature interpretation; raising environmental awareness among the local population; introducing a visitors information programme (including environmental information)

Conclusions

During the last century, the role of beaches has completely reversed: they have become the driving force behind economic welfare instead of just being an inhospitable place. Demographic pressure, excessive land use and related factors, both in the hinterland (e.g. river dams, water diversion) and on the beach itself (e.g. hard coastal protection structures , sand/coral mining), have led to a general decrease in the contribution of sediments to the maintenance of the beaches and foreshores. It is hard to find a unique solution for all those problems. However, the following points are essential:

- The implementation of Integrated Coastal Zone Management

- A better dissemination of the existing information should be achieved. For that purpose, a better coordination of the existing governmental bodies that deal with coastal management is necessary

- Improvement of environmental education is a precondition for sustainable development of the coast

External links

https://www.gstcouncil.org/ The Global Sustainable Tourism Council (GSTC) is managing the GSTC Criteria, global standards for sustainable travel and tourism; as well as providing international accreditation for sustainable tourism Certification Bodies.

Internal Links

- Coastal pollution and impacts

- Threats to the coastal zone

- ↑ Dickhut, H. and Tenger, A. (eds.) 2022. Review and Analysis of Policies, Strategies and Instruments for Boosting Sustainable Tourism in Europe. European SME Going Green 2030 Report, p. 505

- ↑ https://www.f-cca.com/downloads/2018-Cruise-Industry-Overview-and-Statistics.pdf 2018 Cruise Industry Overview]

- ↑ Papathanassis, A. 2022. Cruise tourism. In D. Buhalis (ed), Encyclopedia of Tourism Management and Marketing. Cheltenham: Edward Elgar Publishing, pp. 687–690

- ↑ Moscovici, D. (2017) Environmental Impacts of Cruise Ships on Island Nations, Peace Review, 29: 366-373

- ↑ Caric, H. and Mackelworth, P, (2014) Cruise tourism environmental impacts – The perspective from the Adriatic Sea. Ocean & Coastal Management. 102: 350-363

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 Papathanassis, A. 2023. A decade of ‘blue tourism’ sustainability research: Exploring the impact of cruise tourism on coastal areas. Cambridge Prisms: Coastal Futures 1: 1–11

- ↑ Walker, K. and Moscardo, G. 2016. Moving beyond sense of place to care of place: The role of indigenous values and interpretation in promoting transformative change in tourists’ place images and personal values. Journal of Sustainable Tourism 24: 1243–1261

- ↑ International Tourism Highlights (2019) https://www.e-unwto.org/doi/pdf/10.18111/9789284421152

- ↑ Ecorys (2016) Study on specific challenges for a sustainable development of coastal and maritime tourism in Europe EC Maritime Affairs

- Articles by Lal Mukherjee, Abir

- Reviewed articles

- Integrated coastal zone management

- This page was last edited on 5 May 2023, at 17:28.

- Privacy policy

- About Coastal Wiki

- Disclaimers

- The Ocean’s Importance

What is the Ocean Panel?

Advisory Network

The Agenda: Transformations

Ocean Wealth

Ocean Health

Ocean Equity

Ocean Knowledge

Ocean Finance

Sustainable Ocean Plans

Progress Reports

Action Groups

Sustainable Coastal & Marine Tourism

- Publications

Coastal and marine tourism represents at least 50 percent of total global tourism . It constitutes the largest economic sector for most small island developing states and many coastal states. Securing the long-term sustainability and viability of this sector is critical for the continued prosperity of the destinations and communities that rely on it.

Featured Resources

Accessibility Tools

Privacy overview.

Thank you for visiting nature.com. You are using a browser version with limited support for CSS. To obtain the best experience, we recommend you use a more up to date browser (or turn off compatibility mode in Internet Explorer). In the meantime, to ensure continued support, we are displaying the site without styles and JavaScript.

- View all journals

- Explore content

- About the journal

- Publish with us

- Sign up for alerts

- Brief Communication

- Published: 09 January 2023

Coral reefs and coastal tourism in Hawaii

- Bing Lin ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-5905-9512 1 ,

- Yiwen Zeng 1 ,

- Gregory P. Asner ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0001-7893-6421 2 &

- David S. Wilcove 1 , 3

Nature Sustainability volume 6 , pages 254–258 ( 2023 ) Cite this article

3133 Accesses

2 Citations

106 Altmetric

Metrics details

- Biodiversity

- Conservation biology

- Ecosystem services

- Environmental impact

An Author Correction to this article was published on 14 March 2023

This article has been updated

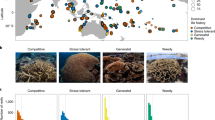

Coral reefs are popular for their vibrant biodiversity. By combining web-scraped Instagram data from tourists and high-resolution live coral cover maps in Hawaii, we find that, regionally, coral reefs both attract and suffer from coastal tourism. Higher live coral cover attracts reef visitors, but that visitation contributes to subsequent reef degradation. Such feedback loops threaten the highest quality reefs, highlighting both their economic value and the need for effective conservation management.

This is a preview of subscription content, access via your institution

Access options

Access Nature and 54 other Nature Portfolio journals

Get Nature+, our best-value online-access subscription

24,99 € / 30 days

cancel any time

Subscribe to this journal

Receive 12 digital issues and online access to articles

111,21 € per year

only 9,27 € per issue

Buy this article

- Purchase on Springer Link

- Instant access to full article PDF

Prices may be subject to local taxes which are calculated during checkout

Similar content being viewed by others

Decadal stability in coral cover could mask hidden changes on reefs in the East Asian Seas

Y. K. S. Chan, Y. A. Affendi, … D. Huang

Social–environmental drivers inform strategic management of coral reefs in the Anthropocene

Emily S. Darling, Tim R. McClanahan, … David Mouillot

The value of US coral reefs for flood risk reduction

Borja G. Reguero, Curt D. Storlazzi, … Michael W. Beck

Data availability

The live coral cover data are available in the Zenodo repository ( https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.4292660 ). The human activity, site accessibility and water conditions data are available through the Ocean Tipping Points project ( http://www.pacioos.hawaii.edu/projects/oceantippingpoints ) and the Hawaii Statewide GIS Program ( https://geoportal.hawaii.gov/search?collection=Dataset ). Meta reached out to the authors after publication and asked that the original Instagram dataset uploaded in the accompanying Zenodo repository be removed from public access to limit user data exposure and its risk of misuse.

Code availability

Meta reached out to the authors after publication and asked that the original web-scraping script uploaded in the accompanying Zenodo repository be removed from public access to limit user data exposure and its risk of misuse.

Change history

14 march 2023.

A Correction to this paper has been published: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41893-023-01102-y

Hughes, T. P. et al. Global warming and recurrent mass bleaching of corals. Nature 543 , 373–377 (2017).

Article CAS Google Scholar

Arkema, K. K., Fisher, D. M., Wyatt, K., Wood, S. A. & Payne, H. J. Advancing sustainable development and protected area mManagement with social media-based tourism data. Sustainability 13 , 2427 (2021).

Article Google Scholar

Tourism in the 2030 Agenda (UNWTO, 2015); https://www.unwto.org/tourism-in-2030-agenda

Cowburn, B., Moritz, C., Birrell, C., Grimsditch, G. & Abdulla, A. Can luxury and environmental sustainability co-exist? Assessing the environmental impact of resort tourism on coral reefs in the Maldives. Ocean Coast. Manag. 158 , 120–127 (2018).

Lin, B. Close encounters of the worst kind: reforms needed to curb coral reef damage by recreational divers. Coral Reefs 40 , 1429–1435 (2021).

Asner, G. P. et al. Large-scale mapping of live corals to guide reef conservation. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 117 , 33711–33718 (2020).

Wood, S. A., Guerry, A. D., Silver, J. M. & Lacayo, M. Using social media to quantify nature-based tourism and recreation. Sci. Rep. 3 , 2976 (2013).

Wood, S. A. et al. Next-generation visitation models using social media to estimate recreation on public lands. Sci. Rep. 10 , 15419 (2020).

Hausmann, A. et al. Social media data can be used to understand tourists’ preferences for nature-based experiences in protected areas. Conserv. Lett. 11 , e12343 (2018).

Tenkanen, H. et al. Instagram, Flickr, or Twitter: assessing the usability of social media data for visitor monitoring in protected areas. Sci. Rep. 7 , 17615 (2017).

Sessions, C., Wood, S. A., Rabotyagov, S. & Fisher, D. M. Measuring recreational visitation at U.S. National Parks with crowd-sourced photographs. J. Environ. Manag. 183 , 703–711 (2016).

Mancini, F., Coghill, G. M. & Lusseau, D. Using social media to quantify spatial and temporal dynamics of nature-based recreational activities. PLoS One 13 , e0200565 (2018).

Spalding, M. et al. Mapping the global value and distribution of coral reef tourism. Mar. Policy 82 , 104–113 (2017).

van Zanten, B. T. et al. Continental-scale quantification of landscape values using social media data. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 113 , 12974–12979 (2016).

Department of Land and Natural Resources. Beach Access (Office of Conservation and Coastal Lands, 2013); https://dlnr.hawaii.gov/occl/beach-access/

Mobile LTE Coverage Map (Federal Communications Commission, 2021).

Arkema, K. K. et al. Embedding ecosystem services in coastal planning leads to better outcomes for people and nature. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 112 , 7390–7395 (2015).

Neuvonen, M., Pouta, E., Puustinen, J. & Sievänen, T. Visits to national parks: effects of park characteristics and spatial demand. J. Nat. Conserv. 18 , 224–229 (2010).

Rodgers, K., Cox, E. & Newtson, C. Effects of mechanical fracturing and experimental trampling on hawaiian corals. Environ. Manag. 31 , 0377–0384 (2003).

Downs, C. A. et al. Toxicopathological effects of the sunscreen UV filter, oxybenzone (benzophenone-3), on coral planulae and cultured primary cells and its environmental contamination in Hawaii and the U.S. Virgin Islands. Arch. Environ. Contam. Toxicol. 70 , 265–288 (2016).

Côté, I. M., Darling, E. S. & Brown, C. J. Interactions among ecosystem stressors and their importance in conservation. Proc. R. Soc. B. 283 , 20152592 (2016).

Bruno, J. F. & Valdivia, A. Coral reef degradation is not correlated with local human population density. Sci. Rep. 6 , 29778 (2016).

Johnson, J. V., Dick, J. T. A. & Pincheira-Donoso, D. Local anthropogenic stress does not exacerbate coral bleaching under global climate change. Glob. Ecol . Biogeogr. (2022).

Darling, E. S., McClanahan, T. R. & Côté, I. M. Combined effects of two stressors on Kenyan coral reefs are additive or antagonistic, not synergistic. Conserv. Lett. 3 , 122–130 (2010).

Severino, S. J. L., Rodgers, K. S., Stender, Y. & Stefanak, M. Hanauma Bay Biological Carrying Capacity Survey 2019–20 2nd Annual Report https://www.honolulu.gov/rep/site/dpr/hanaumabay_docs/Hanauma_Bay_Carrying_Capacity_Report_August_2020.pdf (City and County of Honolulu Parks and Recreation Department, 2020).

Selenium WebDriver (Software Freedom Conservancy, 2022); https://www.selenium.dev/documentation/en/webdriver/

Geospatial Data Portal. Hawaii Statewide GIS Program (Hawaii State Office of Planning, 2017); https://geoportal.hawaii.gov/

Wedding, L. M. et al. Advancing the integration of spatial data to map human and natural drivers on coral reefs. PLoS One 13 , e0189792 (2018).

Nguyen, T., Liquet, B., Mengersen, K. & Sous, D. Mapping of coral reefs with multispectral satellites: a review of recent papers. Remote Sens. 13 , 4470 (2021).

Wicaksono, P., Aryaguna, P. A. & Lazuardi, W. Benthic habitat mapping model and cross validation using machine-learning classification algorithms. Remote Sens. 11 , 1279 (2019).

Download references

Acknowledgements

We thank T. Bearpark, F. Guo, M. Donovan, A. Friedlander, K. Oleson, J. Lecky and J. Abraham for input that informed the study’s conception, design and analyses; T. W. Shawa for help with geospatial modeling; T. Bearpark, A. M. Zuranski, J. A. G. Torres, B. J. Arnold and N. Ondrikova for input on machine learning models; Z. Volenec for the base Selenium WebDriver Python code; the Ocean Tipping Points project and the Hawaii Statewide GIS Program for all site accessibility, human activity and water condition data; and the High Meadows Foundation and Princeton University for ongoing support of this work. Airborne mapping was funded by the Lenfest Ocean Program of The Pew Charitable Trust.

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Princeton School of Public and International Affairs, Princeton University, Princeton, NJ, USA

Bing Lin, Yiwen Zeng & David S. Wilcove

Center for Global Discovery and Conservation Science, Arizona State University, Hilo, HI, USA

Gregory P. Asner

Department of Ecology and Evolutionary Biology, Princeton University, Princeton, NJ, USA

David S. Wilcove

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Contributions

B.L. conceived this study and wrote the first draft; G.P.A. provided the live coral cover data; B.L. and Y.Z. carried out the analyses with input from G.P.A. and D.S.W.; B.L., Y.Z., D.S.W. and G.P.A. contributed to all subsequent iterations of the manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Correspondence to Bing Lin or David S. Wilcove .

Ethics declarations

Competing interests.

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information.

Nature Sustainability thanks Robert Richmond and the other, anonymous, reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Extended data

Extended data fig. 1 instagram and hawaii tourism authority visitation validation (2018–2021)..

Aggregated Instagram visitation data plotted against yearly daily censuses at the county level conducted by the Hawaii Tourism Authority from 2018 to 2021. The line shows the regression point estimate between variables and the shaded area depicts 95% confidence intervals.

Extended Data Fig. 2 Live coral cover and overall visitation at the 20 most-visited sites in Hawaii.

Overall visitation at the top 20 most-visited sites in the main Hawaiian islands plotted against absolute median live coral cover at each of these sites. The name, location and visitation rank of the top 10 most-visited sites are labeled.

Extended Data Fig. 3 Relationship between overall and on-reef visitation in Hawaii.

The relationship between on-reef and overall visitation across 333 bays and beaches in the main Hawaiian islands. The line depicts the regression point estimate between variables and the shaded region represents 95% confidence intervals.

Extended Data Fig. 4 Littoral buffer construction schematic.

A schematic of how each littoral buffer was constructed in ArcGIS Pro 3.0 for various calculations of benthic composition, human activity, and water conditions at each coastal site.

Extended Data Fig. 5 Histograms of on-reef and overall visitation across coastal sites in Hawaii.

Histograms depicting the discontinuous distribution between high- and low-visitation sites for both overall visitation (top figures) and on-reef visitation (bottom figures) across both the most-visited sites ( n = 100) and all sites ( n = 333).

Supplementary information

Supplementary information, reporting summary, rights and permissions.

Springer Nature or its licensor (e.g. a society or other partner) holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Cite this article.

Lin, B., Zeng, Y., Asner, G.P. et al. Coral reefs and coastal tourism in Hawaii. Nat Sustain 6 , 254–258 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41893-022-01021-4

Download citation

Received : 14 June 2022

Accepted : 15 November 2022

Published : 09 January 2023

Issue Date : March 2023

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1038/s41893-022-01021-4

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

This article is cited by

Not such a rare species, after all insights into drymonema gorgo müller 1883 (cnidaria, scyphozoa), a large and little-known jellyfish from brazil.

- L. S. Nascimento

- M. A. Noernberg

- M. Nogueira Júnior

Aquatic Ecology (2023)

Coastal tourism

EU coastal areas are amongst the most preferred touristic destinations for European and international travellers, making coastal and maritime tourism the biggest, growing sector of the EU Blue Economy in terms of GVA and employment. Coastal tourism comprises recreational activities taking place in the proximity of the sea (such as swimming, sunbathing, coastal walks, and wildlife watching) as well as those taking place in the maritime area, including nautical sports (e.g. sailing, scuba diving, cruising, etc.). Over half of the EU bed capacity is concentrated in regions with a sea border. For the economy of many non-landlocked EU Member States, tourism generates a significant portion of the national revenue. It has a wide-ranging impact on economic growth, employment and social development. Tourism is particularly significant for Southern European countries, such as Spain, Portugal, Italy, Malta and Greece. At the same time, coastal tourism is characterised by high seasonality , with demand concentrated in a limited number of months, usually July and August.

In 2020, Coastal tourism kept generating the largest share of employment and GVA in the EU Blue Economy, with 51% and 26%, respectively. EU Blue Economy Report 2023

The statistics presented in this section originate from the following expenditures by tourists in EU coastal areas: • Accommodation • Transport • Other expenditures (e.g. food, culture, recreational activities, water-sport equipment and clothing).

The sector was hit hard by the COVID-19 pandemic. Because of the COVID-19 pandemic, millions of European citizens suddenly could not travel.

In March 2020, tourism came to a grinding halt, and its turnover did not fully recover until 2022 when the total number of nights spent in EU tourist accommodation reached 2.73 billion (against the pre-pandemic level of 2.88 billion nights in 2019).

In 2022, tourism figures in all months were higher than in 2021, with the fourth quarter of 2022 recording 472 million nights. In total, nights spent went up by 49% compared to 2021 (1.83 billion nights).

In 2020, the GVA generated by the sector amounted to €33.9 billion, down from €81.5 billion registered in 2019, i.e., a year-on-year 58% contraction.

Gross profits, at €3.9 billion, shrunk by more than 85% in 2019.

Click here to read more

While recovering from the Covid-19 pandemic, the Coastal tourism sector has engaged in the sustainability transition with the aim to green its operations, reduce its negative impacts on the marine environment, and strengthen its resilience to exogenous shocks such as commodity and fuel price inflation.

For this purpose, the European Commission has published the Tourism Transition Pathway involving all tourism stakeholders. The updated Industrial Strategy (2021) calls for the acceleration of green and digital transformation to increase the European economy's resilience.

The strategy also identifies 27 initiative areas for the green and digital transition to improve tourism in the EU. These include:

• Regulation and public governance , which includes; improving statistics and indicators for tourism and comprehensive tourism strategies.

• Green and digital transition , which includes; research and innovation projects on circular and climate-friendly tourism and support for digitalisation of tourism SMEs and destinations.

• Resilience , which includes; seamless cross-border travelling, fostering skills in tourism, promoting fairness and equality in tourism jobs, and accessibility.

As part of the EU Sustainable Blue Economy , the coastal and maritime tourism sector has been identified as an area with potential to foster a smart, sustainable and inclusive Europe. The EU's tourism policy aims to keep Europe's position as a leading tourist destination while also maximising the industry's contribution to economic growth and jobs.

![coastal tourism tourists [Bathing boxes on the beach]](https://blue-economy-observatory.ec.europa.eu/sites/default/files/styles/embed_large/public/2022-04/AdobeStock_5838556.jpeg?itok=OihAUMSO)

Interaction with other sectors

While European destinations are welcoming tourists at pre-pandemic levels, the rise in tourist numbers and their concentration in attractive touristic destinations may generate issues of over tourism, particularly in coastal areas and small island. Increasing tourism intensity requires long-term solutions .

At the same time, Covid-19 will likely have long-term impacts on EU citizens’ travelling behavior. A recent Eurobarometer survey showed that 82% of EU citizens are ready to change their travel and tourism habits to be more sustainable, for example, by consuming local products (55%), choosing ecological means of transport (36%) or by paying more to protect the natural environment (35%) or to benefit the local community (33%). The survey also found out that 38% of European respondents are expecting more domestic travelling in the future .

One example of a sustainable approach to coastal and maritime tourism is the ECO-CRUISING FU_TOUR .

For many experts in the business, this is a game-changing opportunity that will lead to greater and faster adoption of more sustainable environmental solutions and greater respect for coastal natural and cultural qualities of coastal areas. The European Green Deal and the new EU Sustainable Blue Economy can help in such green transitions, thanks to policy reforms, specific financial mechanism, as well as innovation, digitalisation, education and training.

Share this page

Coastal Tourism

- Pre-covid-19

10% of all international visitors that arrive in UK go to coast

The Coast comprises a very high rate of SMEs (with less than 3% corporate brands represented)

Coastal Tourism in England is highly seasonal, but change was happening as a result of investment in research, product development and marketing:

Key challenges facing coastal communities:

Seasonality

- Productivity

- Perceptions (consumers, media and government)

Climate Change – coastal storms / flooding Business ownership and investment

- Large number of micro and small businesses – difficult to coordinate and deliver change

- Prior to covid, 28% of businesses said they were “planning to sell / retire in next 5 years”

High dependency on Tourism average 15-20% of employment - but 50%+ in places like St. Ives, Exmoor, Whitby and Newquay

Socio-economic pressures on Coastal Communities Skills Brexit

But there are opportunities:

Addressing seasonality and attracting off peak growth markets

- International visitors

- Domestic visitors - Wellness, Slow tourism, Business Events, Under 35s, Empty nesters (over 55s) and Active Experiences

Wider sector or coastal opportunities…

- England Coast Path

Impact of Covid-19

Pre-COVID spend £13.7bn in England

2020 England – coastal impact of COVID-19

Based on July re-opening, loss of international travel and reduced capacity due to social distancing, November lockdown

Verified with National Business Survey data on capacity and revenue

- 95m trips and day visits

- £7.64bn loss in tourism spend

- Equivalent of circa 131,000 jobs

2021 England – coastal impact of COVID-19

Based on closure Jan-Mar, partial April reopening, very limited international travel, reduced capacity and busy summer

- 44m trips and day visits (-23% on pre-Covid-19)

- £5.15bn loss in tourism spend

- -37% on pre-Covid spend / 41% increase on 2020

Hotel Solutions forecast 20-25% of accommodation in coastal communities will close

Institute of Fiscal Studies - there “is no longer a north-south, or urban-rural divide… coastal areas are notably vulnerable to both the health and economic impacts of the crisis” – especially Isle of Wight, Torquay, Blackpool, Dorset and Northumberland

Other reports highlighting impact on coast

Centre for Towns, The Effect of the COVID-19 Pandemic on our Towns and Cities report 2020 Institute for Employment Studies, Labour Market Statistics June 2020: IES Analysis Social Markets Foundation Report HOPE not hate Charitable Trust, Understanding Community Resilience in Our Towns report 2020 Social Investment Business Group: Covid-19 Coastal Communities The Place Bureau Report

Domestic tourism on the Coast

South west is the most popular region for seaside visits:

Visitor Profile demographics:

Source:GBTS 2019

Socio-economic group

International visitors to the coast

10% visit the English coast at some point during their stay in UK

88% are on break of 4+nights (non coastal visitors = 55% on 4+ night break)

210,000 jobs worth £3.6bn (Sheffield Hallam University 2014) + 1% growth

Higher than average concentration of SMEs in coastal visitor economy

<3% corporate brands on the coast (National Coastal Tourism Academy 2015)

31% of residents work part-time → Net outflow of commuters (ONS 2014)

Contact details

+44(0)1202 093 429 [email protected]

- International edition

- Australia edition

- Europe edition

‘This coast is saturated’: Italian village braces for post-Ripley crowds

Netflix hit series based on Patricia Highsmith novel brings prospect of surge in visitors to Atrani area of Amalfi coast

When Andrew Scott’s eponymous character in the hit new Netflix series Ripley travels from Naples to the village of Atrani, the rickety bus has the road almost to itself; a solitary Vespa passes going the other way. When he tracks down Dickie Greenleaf at the beach, the rich American and his girlfriend are the only people sunbathing on the pristine sands.

Visitors to the Amalfi coast today will note the contrast. Unlike in 1961, the road between Positano and Salerno is now known as much for its traffic jams as for the views. Atrani may be less busy than its neighbour Amalfi, but in summer its beach is taken over by rows of umbrellas and sunbeds. A small area, perhaps a fifth of the space, is public spiaggia libera .

In the village, which has one four-star hotel and a few B&Bs and holiday lets, some businesses are pleased about the Netflix exposure. Antonio Buonocore, who runs the beachside restaurant Le Arcate, said: “The impeccable photography has certainly brought our little village extra publicity.”

But others worry how sustainable this will be. Antonella Florio, of Maison Escher apartments, said: “This coast is saturated with overtourism. If more visitors come because of the series, I sincerely hope they come in low season.”

Luisa Criscolo, property manager at Chiara’s House, agreed: “If tourism does grow, the risk is that it’s not managed intelligently. Our village can’t cope with huge numbers of tourists. Cars, buses and motorbikes leave the traffic paralysed. The authorities need to keep a decent amount of places open longer so some visits can be channelled to other times of year, and must also encourage use of waterborne transport, and offer more frequent services on smaller buses.”

In Patricia Highsmith’s 1955 book The Talented Mr Ripley, Greenleaf is living in fictional Mongibello. The TV crew switched to Atrani after searching the coast for a location to suit their black-and-white period style (inspired by the 2018 illustrated book Neorealismo: The New Image in Italy 1932-1960 ). The series’ production designer, David Gropman, told Netflix he loved Atrani’s “incredible geography … the relationship of the main square to the beach, all of those unbelievable paths, that maze of stairs and corridors”. These all help make early episodes visually arresting. “Su, su, su [up, up, up],” says post office operator Matteo, directing Tom Ripley up to Greenleaf’s house.

That opulent villa, however, is not actually in Atrani, but on the nearby island of Capri. Villa Torricella was built in 1902 in eclectic style – turrets, Moorish colonnades, pointed arches and twisted columns – for an earlier pair of American socialites, Kate Perry and Saidee Wolcott, who hid their gay relationship by portraying themselves as sisters.

The villa, whose onion-domed tower is easily spotted from the ferry, is privately owned, but a one-bedroom apartment with panoramic terrace and the gorgeous tiled floors Johnny Flynn as Dickie is seen pacing around on, is for rent on Airbnb from £189 a night. There is still some summer availability, and plenty in autumn, though this may soon change.

After Ripley was released, Airbnb said it had seen a 93% increase in bookings to the Atrani area, which includes Ravello, a larger town a few miles north-east.

Canny beachgoers can avoid the crowds, though. The London-based musician Adam McCulloch visited last October, taking a bus to Positano – “the beach was rammed” – then a ferry to Amalfi. “We left the crowds behind and walked to Atrani over hills via Torre dello Ziro. Up there, you see no one. After steep steps down to the village, we had a swim, and a drink at Bar Nettuno, then walked the coast road back to Amalfi.”

The makers of Ripley closed the centre of Atrani for a month in October 2021 to take it back to the early 60s, paying local businesses for the disruption. (A year later the cameras descended again for filming of The Equalizer 3, also starring Dakota Fanning , who plays Dickie’s girlfriend, Marge.)

Later in the Netflix series, Ripley’s misdeeds take him to Naples, Rome, Palermo and Venice. In each city, writer-director Steven Zaillian uses paintings by Caravaggio to mirror the 20th-century con artist’s descent into violence, and perhaps his repressed sexuality.

But Rome and Venice are no strangers to film crews or mass tourism. Atrani, permanent population of about 800, is braced for change.

- TV streaming

- Patricia Highsmith

- Andrew Scott

- Dakota Fanning

Most viewed

International tourist figures still millions below pre-COVID levels as slow recovery continues

For two years, Marcela Ribeiro worked three jobs to save for her dream holiday to Australia.

Like millions of people across the globe, the 35-year-old from Brazil had long wanted to explore the country's world-famous destinations, specifically the Great Barrier Reef, World Heritage-listed rainforest and sandy beaches.

"I worked really, really hard, many jobs, to get here," Ms Ribeiro said.

"The flights were very expensive, so I have to watch everything I spend. I can't afford to eat out in the restaurants every day."

It's been a similar story for William Grbava from Canada and Amelia Mondido from the Philippines, who last week arrived in Australia for a holiday.

"It's expensive here, much more than we were expecting. We have only been able to factor in a short stop in Sydney," Mr Grbava said.

"We just had a beer and a pizza in Circular Quay for $50.

"What I really wanted to do was drive up the coast to Brisbane, through Byron Bay and those beautiful towns. That's what I did when I was younger. But with the cost of fuel and car rental, it wasn't possible."

Industry yet to recover to pre-COVID levels

It's been more than four years since Australia's borders suddenly closed to the rest of the world and became one of the most isolated destinations on the globe.

COVID-19 wreaked havoc across the country's economy, but nowhere was the pain as instant or more devastating as in the tourism industry.

In 2019, 8.7 million tourists visited Australia from overseas in an industry that was worth $166 billion.

New figures from Tourism Research Australia show there were only 6.6 million international visitors last year, a deficit of more than 2 million compared to 2019 levels.

Victoria experienced the largest loss in international visits at 33 per cent, followed by Queensland at 24 per cent and New South Wales at 22 per cent.

Nationally, Chinese visitor numbers — which made up the bulk of visitors to Australia pre-pandemic — slumped to 507,000 last year, down from 1.3 million in 2019.

Figures for the month of February show more than 850,000 people visited Australia, an increase of 257,000 for the same time in 2023, but 7.5 per cent less than pre-COVID levels.

Gui Lohmann from Griffith University's Institute for Tourism said there were a number of reasons for the slow return of international visitors.

"The airfares are significantly high and we are under an inflationary situation with labour and food costs," Professor Lohmann said.

"It could be challenging for Australia to reach above 8 million international visitors in the scenario we are in at the moment."

Professor Lohmann said cost-of-living pressures were also at play in the return of international tourists, as was a "reset" in European thinking.

"Many Europeans believe a long-haul trip is quite damaging to the environment and they're also flying less generally," he said.

"Their domestic airline routes no longer exist [and] have been replaced by train trips."

He said China's ongoing economic problems, the war in Ukraine and United States' election were also having an impact.

"It's a much more complicated world we are facing after the pandemic," he said.

A long road to recovery

Oxford Economics has forecast it could take until 2025-26 before Australian tourism returned to pre-pandemic levels.

Tourism Australia, a government agency that promotes holidays, said the strongest markets since borders reopened had been New Zealand, the United States and the United Kingdom.

"We always knew that the recovery of international travel to Australia would take time, and we have continued to see the steady return of international visitors to our shores," a spokeswoman said.

Maneka Jayasinghe, a tourism expert at Charles Darwin University, said affordability was a key factor in attracting visitors Down Under.