Suggested Searches

- Climate Change

- Expedition 64

- Mars perseverance

- SpaceX Crew-2

- International Space Station

- View All Topics A-Z

Humans in Space

Earth & climate, the solar system, the universe, aeronautics, learning resources, news & events.

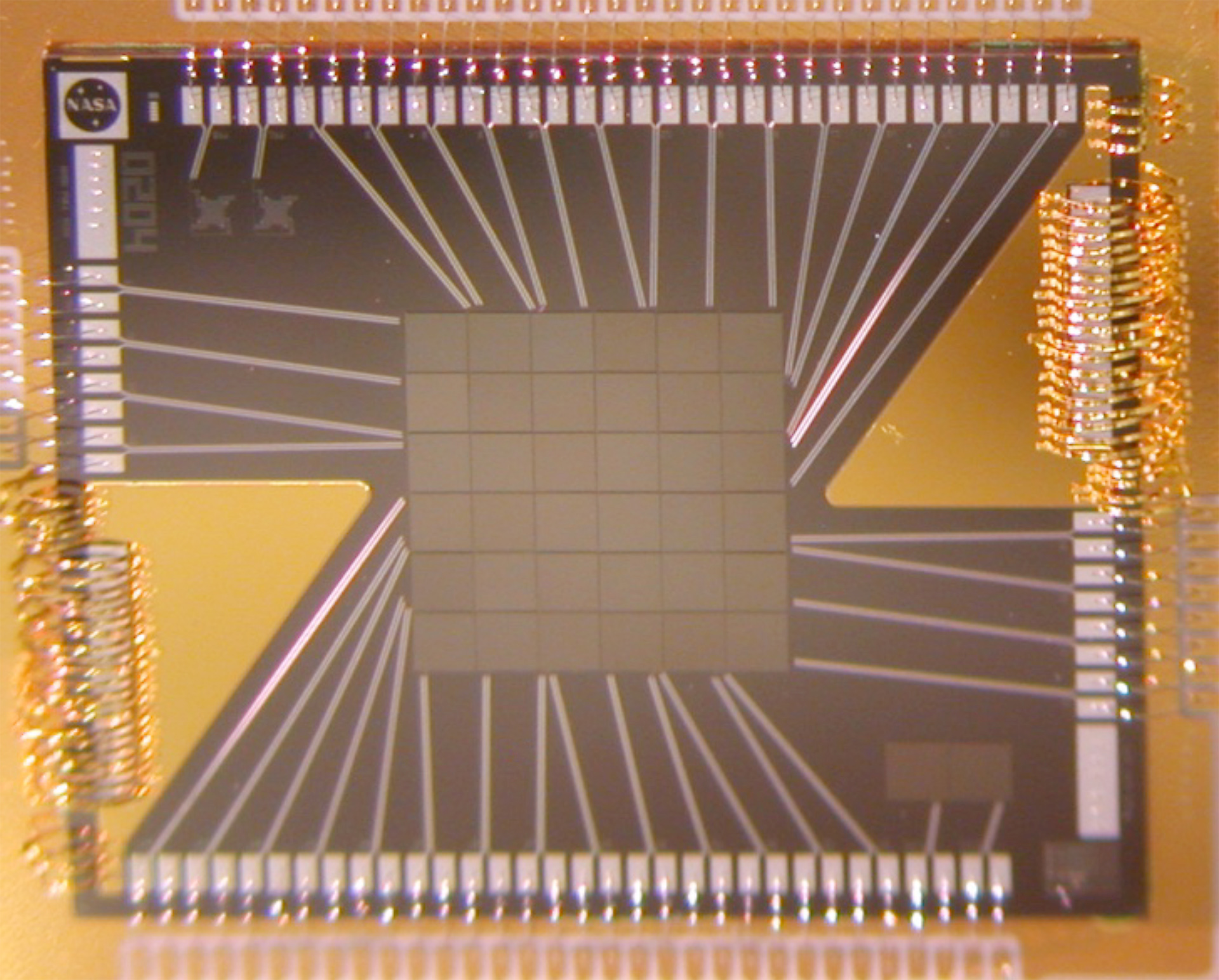

NASA/JAXA’s XRISM Mission Captures Unmatched Data With Just 36 Pixels

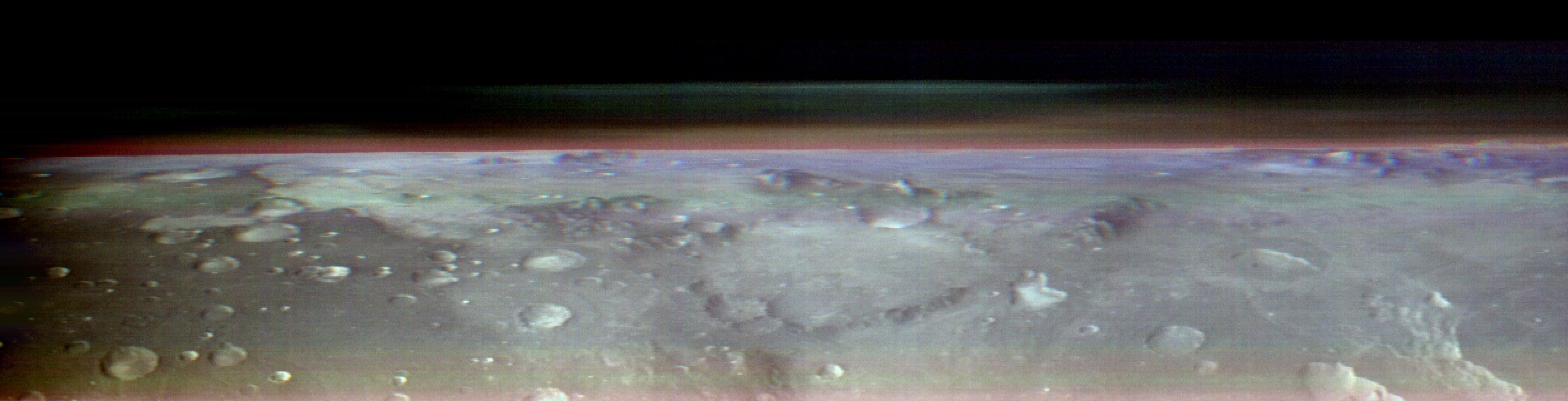

NASA Scientists Gear Up for Solar Storms at Mars

NASA Uses Small Engine to Enhance Sustainable Jet Research

- Search All NASA Missions

- A to Z List of Missions

- Upcoming Launches and Landings

- Spaceships and Rockets

- Communicating with Missions

- James Webb Space Telescope

- Hubble Space Telescope

- Why Go to Space

- Astronauts Home

- Commercial Space

- Destinations

- Living in Space

- Explore Earth Science

- Earth, Our Planet

- Earth Science in Action

- Earth Multimedia

- Earth Science Researchers

- Pluto & Dwarf Planets

- Asteroids, Comets & Meteors

- The Kuiper Belt

- The Oort Cloud

- Skywatching

- The Search for Life in the Universe

- Black Holes

- The Big Bang

- Dark Energy & Dark Matter

- Earth Science

- Planetary Science

- Astrophysics & Space Science

- The Sun & Heliophysics

- Biological & Physical Sciences

- Lunar Science

- Citizen Science

- Astromaterials

- Aeronautics Research

- Human Space Travel Research

- Science in the Air

- NASA Aircraft

- Flight Innovation

- Supersonic Flight

- Air Traffic Solutions

- Green Aviation Tech

- Drones & You

- Technology Transfer & Spinoffs

- Space Travel Technology

- Technology Living in Space

- Manufacturing and Materials

- Science Instruments

- For Kids and Students

- For Educators

- For Colleges and Universities

- For Professionals

- Science for Everyone

- Requests for Exhibits, Artifacts, or Speakers

- STEM Engagement at NASA

- NASA's Impacts

- Centers and Facilities

- Directorates

- Organizations

- People of NASA

- Internships

- Our History

- Doing Business with NASA

- Get Involved

- Aeronáutica

- Ciencias Terrestres

- Sistema Solar

- All NASA News

- Video Series on NASA+

- Newsletters

- Social Media

- Media Resources

- Upcoming Launches & Landings

- Virtual Events

- Sounds and Ringtones

- Interactives

- STEM Multimedia

NASA Balloons Head North of Arctic Circle for Long-Duration Flights

NASA’s Hubble Pauses Science Due to Gyro Issue

NASA’s Commercial Partners Deliver Cargo, Crew for Station Science

NASA Shares Lessons of Human Systems Integration with Industry

Work Underway on Large Cargo Landers for NASA’s Artemis Moon Missions

NASA-Led Study Provides New Global Accounting of Earth’s Rivers

NASA’s ORCA, AirHARP Projects Paved Way for PACE to Reach Space

Amendment 11: Physical Oceanography not solicited in ROSES-2024

Major Martian Milestones

Correction and Clarification of C.26 Rapid Mission Design Studies for Mars Sample Return

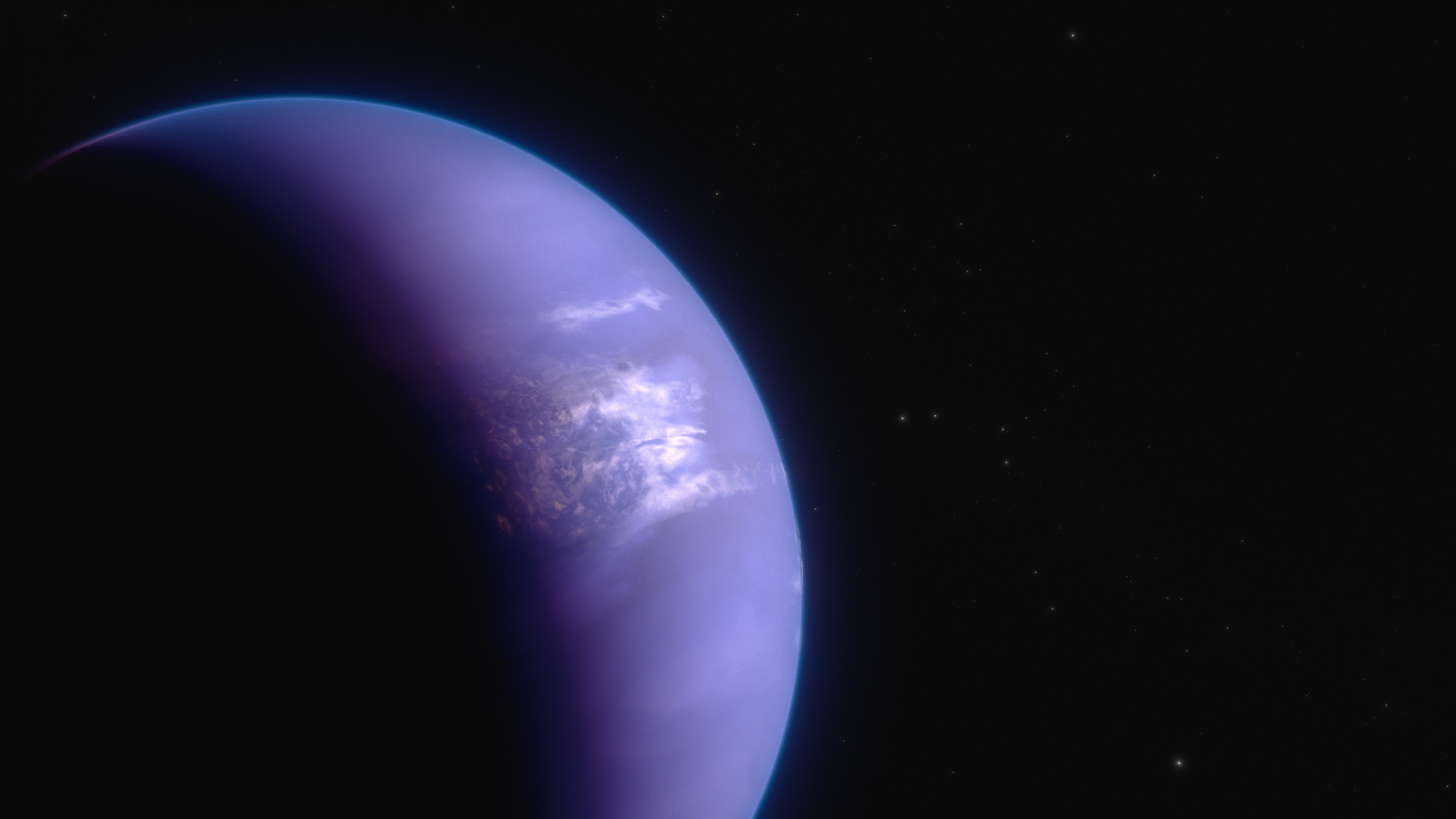

NASA’s Webb Maps Weather on Planet 280 Light-Years Away

Webb Captures Top of Iconic Horsehead Nebula in Unprecedented Detail

NASA Photographer Honored for Thrilling Inverted In-Flight Image

NASA’s Ingenuity Mars Helicopter Team Says Goodbye … for Now

Tech Today: Stay Safe with Battery Testing for Space

NASA Data Helps Beavers Build Back Streams

NASA Grant Brings Students at Underserved Institutions to the Stars

Washington State High Schooler Wins 2024 NASA Student Art Contest

NASA STEM Artemis Moon Trees

NASA’s Commitment to Safety Starts with its Culture

NASA Challenge Gives Space Thruster Commercial Boost

Diez maneras en que los estudiantes pueden prepararse para ser astronautas

Astronauta de la NASA Marcos Berríos

Resultados científicos revolucionarios en la estación espacial de 2023

April 1961 – first human entered space.

Yuri Gagarin from the Soviet Union was the first human in space. His vehicle, Vostok 1 circled Earth at a speed of 27,400 kilometers per hour with the flight lasting 108 minutes. Vostok’s reentry was controlled by a computer. Unlike the early U.S. human spaceflight programs, Gagarin did not land inside of capsule. Instead, he ejected from the spacecraft and landed by parachute.

- History Classics

- Your Profile

- Find History on Facebook (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on Twitter (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on YouTube (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on Instagram (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on TikTok (Opens in a new window)

- This Day In History

- History Podcasts

- History Vault

This Day In History : April 12

Changing the day will navigate the page to that given day in history. You can navigate days by using left and right arrows

Soviet cosmonaut Yuri Gagarin becomes the first man in space

On April 12, 1961, aboard the spacecraft Vostok 1, Soviet cosmonaut Yuri Alekseyevich Gagarin becomes the first human being to travel into space . During the flight, the 27-year-old test pilot and industrial technician also became the first man to orbit the planet, a feat accomplished by his space capsule in 89 minutes. Vostok 1 orbited Earth at a maximum altitude of 187 miles and was guided entirely by an automatic control system. The only statement attributed to Gagarin during his one hour and 48 minutes in space was, “Flight is proceeding normally; I am well.”

After his historic feat was announced, the attractive and unassuming Gagarin became an instant worldwide celebrity. He was awarded the Order of Lenin and given the title of Hero of the Soviet Union . Monuments were raised to him across the Soviet Union and streets renamed in his honor.

The triumph of the Soviet space program in putting the first man into space was a great blow to the United States, which had scheduled its first space flight for May 1961. Moreover, Gagarin had orbited Earth, a feat that eluded the U.S. space program until February 1962, when astronaut John Glenn made three orbits in Friendship 7 . By that time, the Soviet Union had already made another leap ahead in the “space race” with the August 1961 flight of cosmonaut Gherman Titov in Vostok 2 . Titov made 17 orbits and spent more than 25 hours in space.

To Soviet propagandists, the Soviet conquest of space was evidence of the supremacy of communism over capitalism. However, to those who worked on the Vostok program and earlier on Sputnik (which launched the first satellite into space in 1957), the successes were attributable chiefly to the brilliance of one man: Sergei Pavlovich Korolev. Because of his controversial past, Chief Designer Korolev was unknown in the West and to all but insiders in the USSR until his death in 1966.

Born in the Ukraine in 1906, Korolev was part of a scientific team that launched the first Soviet liquid-fueled rocket in 1933. In 1938, his military sponsor fell prey to Soviet leader Joseph Stalin’s purges, and Korolev and his colleagues were also put on trial. Convicted of treason and sabotage, Korolev was sentenced to 10 years in a labor camp. The Soviet authorities came to fear German rocket advances, however, and after only a year Korolev was put in charge of a prison design bureau and ordered to continue his rocketry work.

In 1945, Korolev was sent to Germany to learn about the V-2 rocket, which had been used to devastating effect by the Nazis against the British. The Americans had captured the rocket’s designer, Wernher von Braun, who later became head of the U.S. space program, but the Soviets acquired a fair amount of V-2 resources, including rockets, launch facilities, blueprints, and a few German V-2 technicians. By employing this technology and his own considerable engineering talents, by 1954 Korolev had built a rocket that could carry a five-ton nuclear warhead and in 1957 launched the first intercontinental ballistic missile.

That year, Korolev’s plan to launch a satellite into space was approved, and on October 4, 1957, Sputnik 1 was fired into Earth’s orbit. It was the first Soviet victory of the space race, and Korolev, still technically a prisoner, was officially rehabilitated. The Soviet space program under Korolev would go on to numerous space firsts in the late 1950s and early ’60s: first animal in orbit, first large scientific satellite, first man, first woman, first three men, first space walk, first spacecraft to impact the moon, first to orbit the moon, first to impact Venus, and first craft to soft-land on the moon. Throughout this time, Korolev remained anonymous, known only as the “Chief Designer.” His dream of sending cosmonauts to the moon eventually ended in failure, primarily because the Soviet lunar program received just one-tenth the funding allocated to America’s successful Apollo lunar landing program.

Korolev died in 1966. Upon his death, his identity was finally revealed to the world, and he was awarded a burial in the Kremlin wall as a hero of the Soviet Union. Yuri Gagarin was killed in a routine jet-aircraft test flight in 1968. His ashes were also placed in the Kremlin wall.

Also on This Day in History April | 12

Martin Luther King Jr. is jailed in Birmingham

This Day in History Video: What Happened on April 12

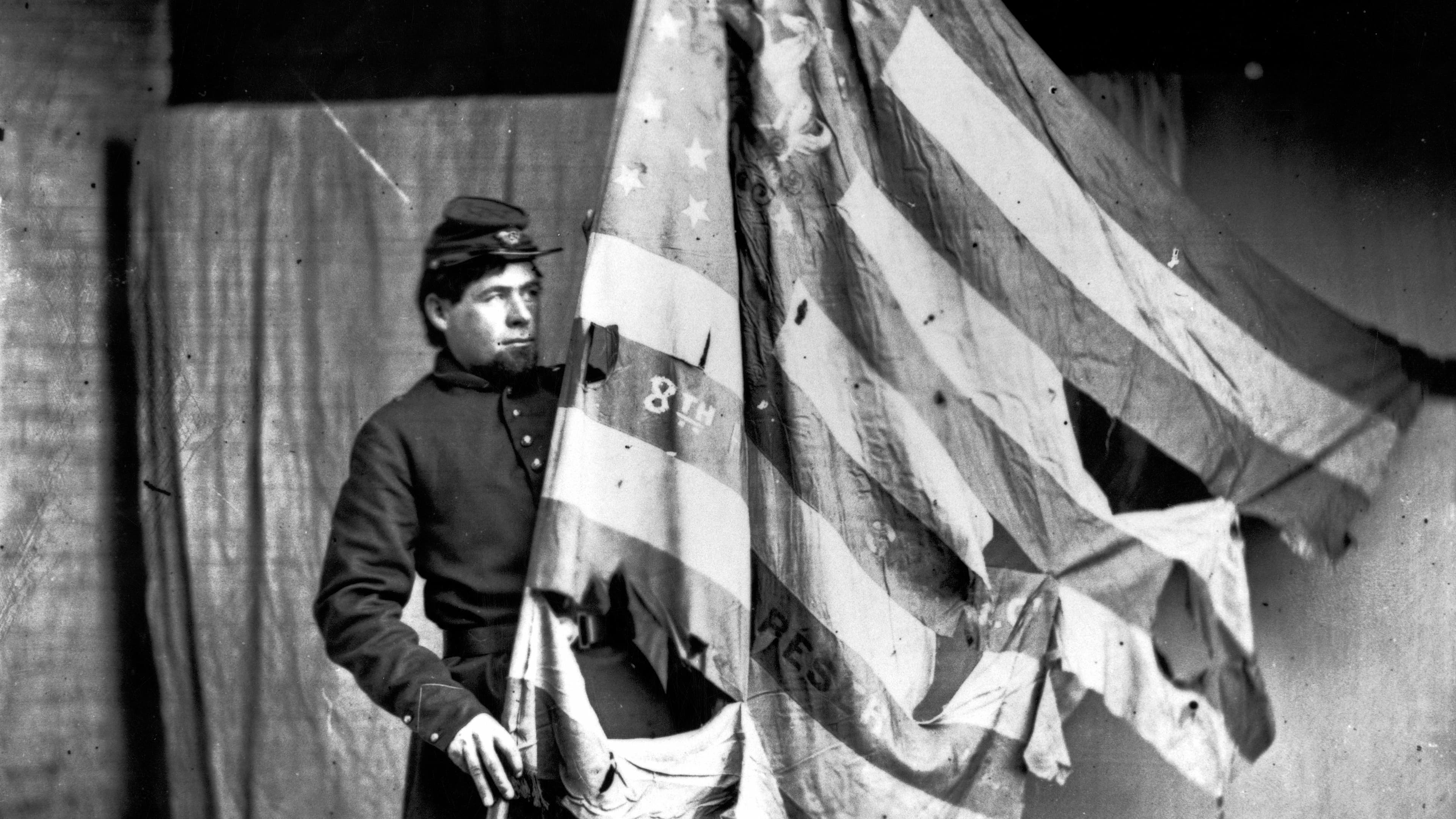

Hundreds of union soldiers killed in fort pillow massacre, bill haley and his comets record “rock around the clock”, the space shuttle columbia is launched for the first time, civil war begins as confederate forces fire on fort sumter.

Wake Up to This Day in History

Sign up now to learn about This Day in History straight from your inbox. Get all of today's events in just one email featuring a range of topics.

By submitting your information, you agree to receive emails from HISTORY and A+E Networks. You can opt out at any time. You must be 16 years or older and a resident of the United States.

More details : Privacy Notice | Terms of Use | Contact Us

U.S. Embassy in Cambodia evacuated

Galileo goes on trial for heresy

Soviets admit to katyn massacre of world war ii, british king approves repeal of the hated townshend acts, canadians capture vimy ridge in northern france.

April 12, 2021

First in Space: New Yuri Gagarin Biography Shares Hidden Side of Cosmonaut

It’s been 60 years, to the day, since Soviet cosmonaut Yuri Gagarin was the first human to travel to space in a tiny capsule attached to an R-7 ballistic missile, a powerful rocket originally designed to carry a three- to five-megaton nuclear warhead. In this new episode marking the 60th anniversary of this historic space flight—the first of its kind— Scientific American talks to Stephen Walker, an award-winning filmmaker, director and book author, about the daring launch that changed the course of human history and charted a map to the skies and beyond.

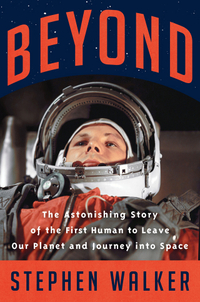

Walker discusses his new book Beyond: The Astonishing Story of the First Human to Leave Our Planet and Journey into Space , out today, and how Gagarin’s journey—an enormous mission that was fraught with danger and planned in complete secrecy—happened on the heels of a cold war between the U.S. and the Soviet Union and sparked a relentless space race between a rising superpower and an ailing one, respectively.

Walker, whose films have won an Emmy and a BAFTA, revisits the complex politics and pioneering science of this era from a fresh perspective. He talks about his hunt for eyewitnesses, decades after the event; how he uncovered never-before-seen footage of the space mission; and, most importantly, how he still managed to put the human story at the heart of a tale at the intersection of political rivalry, cutting-edge technology, and humankind’s ambition to conquer space and explore new frontiers.

By Pakinam Amer

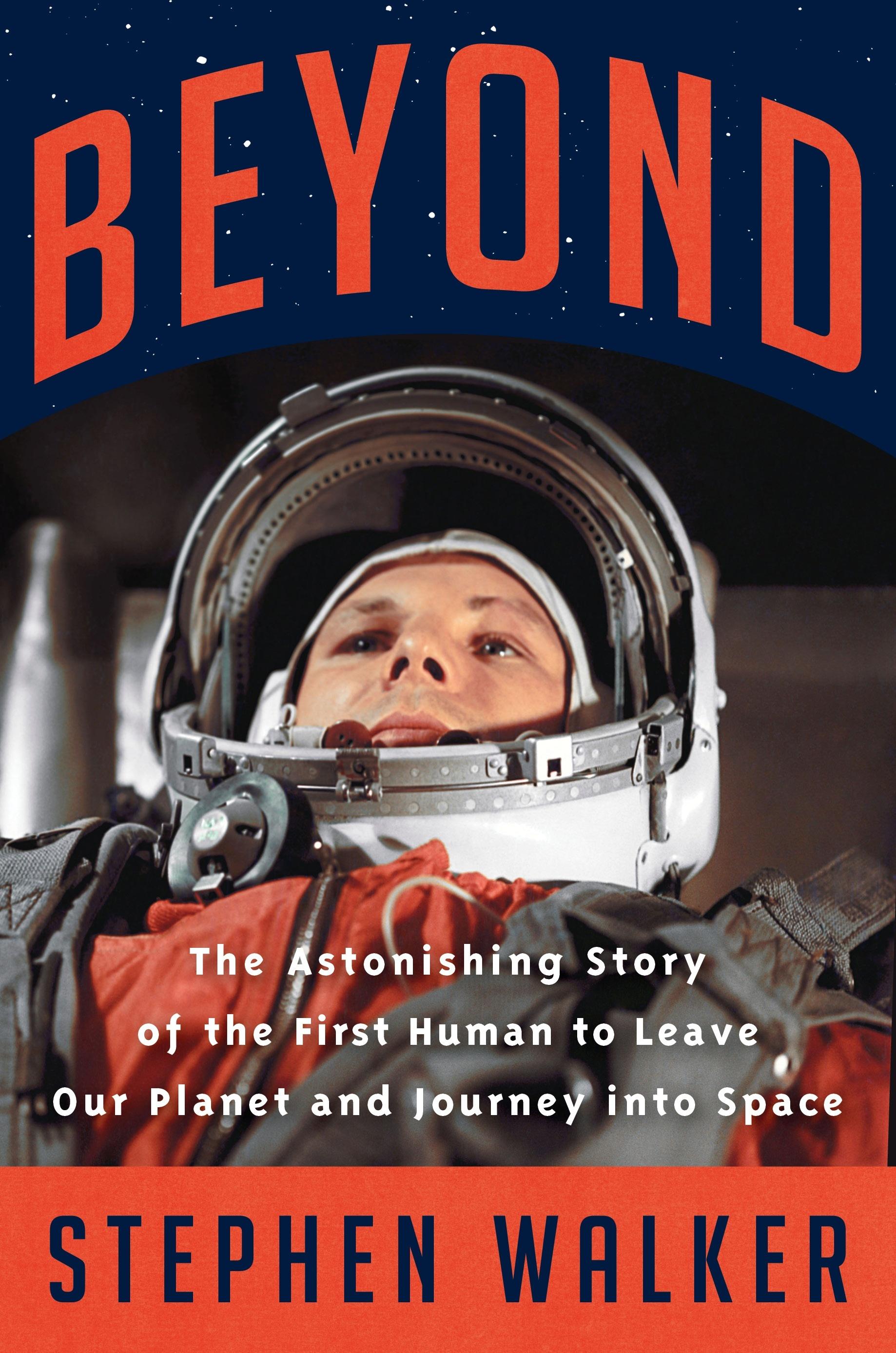

Soviet cosmonaut Yuri Gagarin, the first human to journey into outer space.

Getty Images

Pakinam Amer: It was at 09.07 am Moscow time on April 12, 1961 that a new chapter of history was written. On that day, without much fanfare, Russia sent the first human to space and it happened in secrecy, with very few hints in advance.

Yuri Gagarin, 27-year-old Russian ex-fighter pilot and cosmonaut, was launched into space inside a tiny capsule on top of a ballistic missile, originally designed to carry a warhead.

The spherical capsule was blasted into orbit, circling the Earth at a speed of about 300 miles per minute, 10 times faster than a rifle bullet.

On supporting science journalism

If you're enjoying this article, consider supporting our award-winning journalism by subscribing . By purchasing a subscription you are helping to ensure the future of impactful stories about the discoveries and ideas shaping our world today.

Accounts vary on exactly how long Gagarin spent circling our blue planet before he re-entered the atmosphere, hurtling towards Earth, gravity rapidly pulling him in.

Some say it was 108 [ one hundred and eight ] minutes. Stephen Walker, my guest today and the author of a new book on Gagarin’s historic feat and the world it happened in, puts at 106 [ one hundred and six ].

Give or take a few minutes, that space venture aboard Vostok 1 — orbiting the earth at a maximum altitude of roughly 200 miles and putting the first man in space — still set the record for space achievement.

It sparked a space race between the US and Russia that, 8 eight years later, put other men on the moon for that small step hailed as a giant leap.

It is said that Gagarin whistled a love song as his capsule prepared for launch

One man, five feet five, in an orange space suit, strapped into a seat inside a capsule attached to a modified R-7, the world’s first intercontinental ballistic missile. …

… 106 minutes or 108, man’s first pilgrimage around the planet we call home

... a solitary journey that is still celebrated as monumental and game-changing 60 years on.

This is Pakinam Amer, and you’re listening to Science Talk, a Scientific American podcast. And today, my guest Stephen Walker and I will talk about a legendary astronaut and a super secret space mission that changed everything.

Stephen Walker: [I] came across a book that was written by a guy called [Vladimir] Suvorov who had kept a diary, a secret diary of the secret Soviet space program which he was filming from about 1959 right the way through into the 60s and it was fascinating because it was so secret that he wasn't even able to tell his wife what he was doing but he was away filming all this stuff and he says in his diary this felt like science fiction.

It was just so incredible what was happening in secret and I thought myself I want to find the footage because if I can find that footage which is apparently shot in color and on 35 millimeter I can appraise that footage and turn it into a theatrical feature film which gives you the inside image, the inside sight into this incredible first step to space to the beyond.”

That was Stephen Walker, British director and New York Times bestselling author of Shockwave: Countdown to Hiroshima. And this was his attempt to dust off decades-old footage showing months of preparing Vostok 1 to put a Soviet citizen into orbit before the Americans.

Stephen traveled to Russia, tracked down eye witnesses who worked at the top secret rocket site in the USSR, shot the interviews in high-definition and gathered some raw, never-before-seen insider material shot between 1959 and 61, that he describes as pristine.

But he couldn’t get access to the rest of the footage. What he had was great but wasn’t enough for a full feature film.

So instead, he wrote a book.

It’s called Beyond and it’s published by HarperCollins.

Pakinam Amer: So Stephen, you’re one of those people who actually wrote a book in lockdown.

Stephen Walker: It was incredibly exciting in a way but it was weird, because all this other stuff was going on outside. And I didn't see it. Really. Of course, I did see it. But when people talk about Corona for me at that point, I wasn't thinking about the Coronavirus, I was thinking about the corona spy satellite system that the Americans had in 1961, which I talk about in my book where they were spying on secret Soviet missile complexes. I mean, I was in a different world. I was literally in 1961. And I was also in 2020. It was a really weird experience>

Pakinam Amer: But you began weaving the yarn in 2012?

Stephen Walker: Yeah, I mean, I've done lots of other things since then. I did three trips to Russia. One in 2012. One in 2013. I think I actually had another in 2014 or 2015. The last one was actually a short trip to St. Petersburg, where I met this incredible couple and one of things is wonderful about the Soviet space program at that time, was that actually very unlike NASA, which seemed to have a real major problem about women being anywhere near NASA.

I mean, actually women were not even allowed in the launch blockhouses at Cape Canaveral in 1961. They were forbidden to get in them … There was one woman, a wonderful woman, I interviewed called Joanne Morgan, who was the only woman engineer of all of them [who was allowed] in the launch Center at Kennedy Space Center in 1969. For the moon landing, she's the only one woman and everybody else is a guy. And back in 61, she was telling me over crab cocktails in Cape Canaveral. She told me that you know, she was actually not even allowed to go into the launch of the launch blockhouse, she was forbidden to go in.

Whereas actually in the USSR, oddly enough, it wasn't like that. And I interviewed this couple called Vladimir and Khionia Kraskin, and they're in my book. And they were this wonderful husband and wife in their 80s. And they entertained me in this wonderful little Soviet-style flat in Saint Petersburg, and told me glorious stories about how they were both engineers, telemetry engineers, that have moved there with their child to this weird place in the middle of the Kazakh Steppe, you know, where this new rocket cosmodrome was being built.

And they actually were working right at the epicenter of the Soviet space program, and for that matter, the Soviet missile program, and these were their glory days. It was quite an incredible thing to sort of talk to them both about and they were there when Gagarin launched and with all of that stuff, they were there all the way through it. It was wonderful; it was so Russian, we ended up sitting and drinking vodka until four o'clock in the morning.

I interviewed them on camera, and we had this wonderful, it was quite glorious. This guy had actually out of chocolate wrappers from Ferrero Roche chocolates had constructed a two-meter-high replica of the R-7 rocket that took Yuri Gagarin into space and it was in his sitting room. It was Incredible. It was all made out of chocolate, you know, gold wrappers, it was beautiful.

And, and so I kind of fell in love with these people. And I also sort of felt, you know, I want to tell their stories because they just aren't being heard by anybody. It's all moon, moon, moon, lunar, lunar, lunar. And that's great. Don't get me wrong, it's really important. It's a landmark. It's all of that I get it. But this is an amazing story. And these are amazing stories that people don't know about, and they are really exciting, and really dramatic and really touching and really moving and really, you know, epoch changing, in my opinion.”

Pakinam Amer: Stephen, when I read your book, it almost felt like a novelization of that era. It's a very intricate and intimate account of the people who were involved in that space mission. A very rich account, not just of the orbit itself, but of the tensions reminiscent of the cold war between the US and the Sovient Union, then the space race. But yours is primarily a human story. What inspired you to write it, decades down the line?

Stephen Walker: It is a major philosophical leap for humankind, this is not just advanced Soviet v. America, it really isn't. And to think of it in those terms, is to miss the essential point. Because what I believe

is that the first human being in space is one of the most epoch call moments in all human history.

For essentially three and a half billion years since, or any life began on this planet, anything, okay? This man is the first to leave, he is the first human eye to look down on the biosphere from outside, he is the first--to use the words of Plato--he is the first to escape the cave that we are all in. He steps into the beyond; it is that very first step outside. Nobody had seen this before.

It is one of the things that when you actually put yourself back into that world at that time, and Gagarin very quickly became the most famous man on the planet. You understand why? Because what this is all pre-moon, none of that had happened is this guy was seeing something that no one else in all history whether a human or anything had ever seen. When he looked out in that porthole window, he saw the stars, he saw the earth. And he saw a sunrise in fast motion, and a sunset in fast motion. He saw the incredible fragility of the earth. He saw what we're all destroying, frankly, right now, he saw all of that. And he was the first to see it.

So for me, that is a philosophical psychological quarter, which will be emotional, it is somebody stepping out of the cave into the sunlight as it were to pursue the metaphor and blinking in the light and going, Oh, my God, what's this? What's this that's out here? What is this? He was the first to do it at incredible risk.

It happened because of the politics. It happened because of the race. It happened because of the iron curtain. We know all of those things are valid at all that but actually, in the end, the event, the achievement, better than that the moment is bigger than all of those things way, way, way bigger than all of those things, three and a half billion years. And something changes on April the 12th 1961, at you know, ten past nine in the morning, Moscow time. And that's this. And that's the story.

So for me, it's everything. That's the first thing that kind of animated me to write the book. And I felt that I even had a sign above my desk saying, “remember, Stephen, three and a half billion years, remember,” I kept thinking that when I started to get into the politics too much or got a bit lost in whatever details, as one always does, and pull back from it. What is this really about?

And the other thing that I thought was really important about this. And it animated my writing too. I'm not interested in writing history books that end up in library stacks for decades. I mean, I'm a filmmaker. I want to reach people. And what I tried to do in this story was tell people about people. What interests me most of all, I'm interested, obviously in the technical achievement and really interested in the politics. Of course I am. I couldn't write this book if I wasn't. But what I'm really, really interested in people.

Who was this guy? What was this rivalry like between him and this guy, Titov? He was [the Soviet] number two.

There's an incredible story there, which I kind of talked about, where you get these two men who are both competing to be the first human in space. They are best friends. They are next door neighbors. And they have a child each the same kind of age little infant child, but Titov's child Igor dies at the age of eight months, right in the middle of their Cosmonaut Training, and the Gagarin husband and wife with their own child about the same age, a little girl ... they are incredible to him. They are and his wife, Tamara, they are locked in embrace, they are supportive, they are wonderful. And I know this because I interviewed Titov's wife in Moscow. And she told me all of this, it was quite incredible. She was in tears when she told me this stuff.

And yet, these two men with this love with this tragedy that they kind of shared and helped each other through living next door and on adjoining balconies and crossing over each other's balconies to spend time with each other and late nights talking and drinking vodka and all those sorts of things. They're also rivals for immortality, effectively. And we're not really talking about Titov today, we're talking about Yuri Gagarin. So he lost, he lost. And yet underlying that rivalry is love.

And to me, that becomes human that becomes rich and interesting. It's not just ‘Oh, who came first,’ it's actually a real, it's a relationship of brothers, with all the complexities that fraternal relationships like that would have, you know, the rivalry, the kind of male rivalry, but also the love and the connection in the background. So it's complicated, difficult, it doesn't fit easily into boxes, but a very, very human mix of emotions that drives forward. So characters, people who make the story, this pivotal moment in human history happen, is what really excites me.

Pakinam Amer: Stephen painted an interesting picture of the world where Gagarin’s extraordinary mission happened. How back then, the Soviet Union and the United States were head to head, taking colossal risks in the race to be first in space.

Before Gagarin’s mission, the Soviet Union had already blasted the first satellite in into space, Sputnik 1.

Only three weeks after Gagarin’s earth orbit, American astronaut Alan Shepard--part of the so-called Mercury-7--was launched into space aboard a rocket called Freedom 7.

Less than a year later, John Glenn became the first American to orbit the Earth, circling it three times in 1962.

But Gagarin’s leap into the unknown, being a first, was terrifying.

No one knew what would happen to a person once they’re launched into space. Would they go mad? Can their body withstand it?

Like Stephen aptly describes, there was no textbook for that mission … anywhere. So what exactly were the challenges …

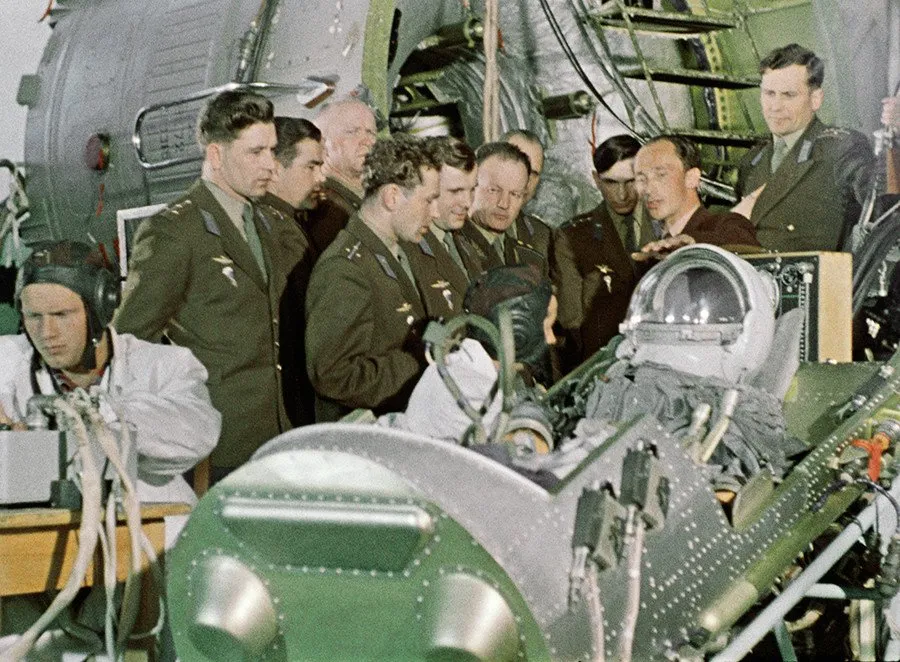

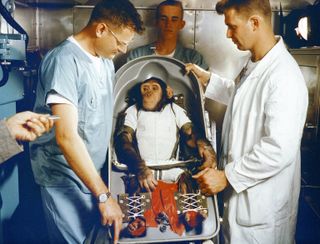

Stephen Walker: The challenges are physiological and psychological, the physiological challenges, some of which had been kind of looked at and dealt with some of the animal flights they do, which I write about in the book with dogs in a Soviet Union and with monkeys, and then finally, obviously a chimpanzee called Ham in the United States. But what actually, they didn't know really was what a human physiology would do in that environment.

So what you're talking about are unbelievable, first of all, acceleration forces in a rocket. Nobody, let's just get this really clear. From the beginning. Nobody had sat on top of a nuclear missile, replacing the nuclear bomb, and then firing it upwards, nobody.

And this particular missile, the R-7, was the biggest missile in the world, it was much bigger than any missile the Americans had, it was powerful enough to fly from Kazakhstan, to New York with a thermonuclear weapon on top of it... It was astonishingly radically advanced for its time. And no human had sat on top of one with a million pounds of thrust and lit the fuse and see what happens.

So they didn't know. I mean, it could blow up straight there on the pad. It could be that the physiological experiences, the actual acceleration, or G-forces could be too much for a body to withstand. And once this rocket had actually got into orbit, and the capsules there, nobody knew what weightlessness would do to a human body.

There were real fears that a human wouldn't be able to breathe properly, even obviously, in an oxygenated atmosphere. The human being wouldn't be able to swallow, for example, that weightlessness would do really, really strange things to the heart, they wouldn't beat properly. You know, nobody knew because nobody experienced weightlessness of any kind for more than a few seconds in one of those aeroplanes that simulated weightlessness with his parabolas, they kept flying. But that was only for about 20 seconds. This is going to be much, much longer than that.

So they just didn't know. They were tremendous concerns about how he'd get down again, everybody knew that a capsule returning through the atmosphere would build up massive amounts of friction, the temperatures would reach 1500 degrees centigrade, even more, you know, would it burn away? Would whatever protection he had in the form of a heat shield, or in the design of the capsule itself? Would it work already burn up as he came down? You know, would that be a problem?

And then, beyond all of those problems, there was, as I said, the psychological problem. And the psychological problem basically boiled down to very simple sentence, or rather a very simple question, but with a very simple answer. And that was, would he go insane? Was he going mad in space, because the real fear, and it was a real fear at that time.

And there were, there was psychological textbooks that were written about something called space horror , was that the first human being divorced from the planet below divorce from life or life as we know it divorce for all of that sailing alone, and this is ultimate loneliness or isolation, in the vacuum of space in his little sphere, might go mad.

So they had to think about that, too. And what they thought about as I described in my book was a very Soviet response, they decided that flight will be completely automated. So the guy wouldn't have to do anything at all inside it, except essentially endure it, whatever “endure” actually meant. But they then decided at the last moment, that if actually, something did go wrong, and he needed to take manual control, then how are they going to let him have manual control.

And they came up with this extraordinary solution, which is just utterly mad, where they basically had a three digit code, which you press on, like, the kind of thing you have in a hotel safe on the side of his capsule, and you press these three numbers, which I think will one to five; it's in the book, and that would unlock the manual controls. But then they worried that he might go so crazy that he might just do that anyway, take control, and God knows what he'll do, you know, destroy himself, defect to America, in his spacecraft.

These were proper discussions that took place, literally a few days before he flew. And in the end, what they decided to do was to put the code in an envelope, and seal the envelope, and glue it somewhere in the lining of the inside of his spacecraft. The idea being somehow-- this is crazy logic, it's not even logic-- that if he was able to find it, open it, read the code and press the correct numbers, then he won't be insane. And that was seriously discussed in a state commission of the top politicians, KGB people and space engineers, one week before Yuri Gagarin flew in space.

That's, that's what they dealt with, because they were they didn't know space, horror, insanity. So you're, again, it comes back to my saying at the very beginning, everything here is a first everything is an unknown, nobody's done it before. Nobody. And what increases that feeling of isolation that would have made the possibility of insanity a real one. Why they were so frightened was because they didn't have reliable radio communications with the ground.

They didn't have what the [American] Mercury astronauts would have, which was a chain of stations basically, in circling the globe, where they would always have somebody to talk to, and we're very used to the moon landings and there's all those, you know, communications with beeps on the end, and even with Apollo 13, the one that went wrong, they're always communicating with Mission Control in Houston. But for Gagarin's flight, I would say a substantial part of his flight.

I'm not sure if you'd actually say the majority, but a substantial part of his flight hidden nobody's talked to. He had nobody to talk to, except a microphone with a tape recorder that was installed inside his cabin. And as I say, in the book, it turns out that whoever installed the tape in the tape recorder didn't put enough tape in. So he ran out halfway around the world. And he sat there and made probably one of the few independent decisions that he made in the cabinet, in that Vostok spacecraft, which was to rewind the tape to the beginning, and then record over everything he just said. This is the first mind in space and that's what happened.

You can't really make this stuff up.

Although the radio communication with the first human who stepped beyond our planet involved few words, what we know for instance was that Yuri’s first spoken words were, “The Earth is blue, how wonderful,” Stephen includes part of the transcript of the tape that Yuri recorded during orbit aboard the capsule, as he looked out of the porthole of his capsule.

“The Earth was moving to the left, then upwards, then to the right, and downwards … I could see the horizon, the stars, the Sky,” Gagarin said. “I could see the very beautiful horizon, I could see the curvature of the Earth.”

Pakinam Amer: You’ve heard from Stephen Walker, filmmaker and author of Beyond: The Astonishing Story of the First Human to Leave Our Planet and Journey into Space. His book is on sale today. You can get it through HarperCollins, its publisher, or wherever you buy your books. For more information visit www.stephenwalkerbeyond.com

That was Science Talk, and this is your host Pakinam Amer. Thank you for listening.

- International edition

- Australia edition

- Europe edition

Sergei Korolev: the rocket genius behind Yuri Gagarin

I t remains the one untarnished triumph of Soviet science. On 12 April 1961, a peasant farmer's son with a winsome smile crammed himself into a capsule eight feet in diameter and was blasted into space on top of a rocket 20 storeys high. One hundred and eight minutes later, after making a single orbit of our world, the young pilot parachuted back to Earth. In doing so, Yuri Gagarin became the first human being to journey into space.

The flight of Vostok 1 – whose 50th anniversary will be celebrated next month – was a defining moment of the 20th century and opened up the prospect of interplanetary travel for our species. It also made Gagarin an international star while his mission was hailed as clear proof of the superiority of communist technology. The 27-year-old cosmonaut became a figurehead for the Soviet Union and toured the world. He lunched with the Queen; was kissed by Gina Lollobrigida; and holidayed with the privileged in Crimea.

Gagarin also received more than a million letters from fans across the world, an astonishing outpouring of global admiration – for he was not obvious star material. He was short and slightly built. Yet Gagarin possessed a smile "that lit up the darkness of the cold war", as one writer put it, and had a natural grace that made him the best ambassador that the USSR ever had. Even his flaws seem oddly endearing by modern standards, his worst moment occurring when he gashed his head after leaping from a window to avoid his wife who had discovered a girl in his hotel room.

To many Russians, Gagarin occupies the same emotional territory as John F Kennedy or Princess Diana. The trio even share the intense attention of conspiracy theorists with alien abduction, a CIA plot and suicide all being blamed for Gagarin's death in 1968.

At the same time, his flight's anniversary will give Russians a chance to reflect on the former might of the Soviet empire. Ravaged by a war that had killed more than 26 million of its citizens, the USSR learned, within a generation, how to orbit satellites, aim probes at the moon and finally put a man into space. It was an extraordinary demonstration of the might of the Soviet people. At least, that is what was claimed at the time.

In fact, Gagarin's flight was anything but a collective affair. In the years that have followed the USSR's disintegration, it has become clear that his mission was a highly individualistic business with one man dominating proceedings: Sergei Korolev, the chief designer – a shadowy figure who was only revealed to have masterminded the USSR's rocket wizardry after his death in 1966. The remarkable story of his genius, his survival in the Gulags; his transformation into one of the most powerful men in the Soviet Union – and his interaction with his favourite cosmonaut, his "little eagle" Yuri Gagarin, is the real story behind that flight on 12 April 1961. Gagarin became the face of Soviet space supremacy, while Korolev was its brains. The pair made a potent team and their success brought fame to one and immense power to the other. Neither lived long to enjoy those rewards, however.

The man who would lead the world into the space age, Sergei Pavlovich Korolev, was born on 12 January 1907, in Zhitomir, in modern-day Ukraine. His mother Maria left her husband Pavel while Sergei was young and remarried – though Korolev went on to have a good relationship with his stepfather. Like Gagarin, he was besotted with flying and aeronautics and studied in Moscow under Andrei Tupolev, the distinguished Soviet aircraft designer. Tupolev described his young student "as a man with unlimited devotion to his job and his ideas".

Korolev qualified as a pilot and began designing gliders to which he added rocket engines. In 1933, he successfully launched the first liquid-fuelled rocket in the USSR. He prospered for he was hard-working and loyal to the Soviet system. It was not enough. On 27 June 1938, four secret service agents broke into his apartment and arrested him as a spy. Korolev was beaten. He asked for a glass of water and a jailer smashed the jug in his face. In the end, Korolev was forced to admit to crimes of treason and sabotage and was sentenced to 10 years' hard labour at the Kolyma gold mine, the most notorious of all Gulag prison camps. Korolev never found out why he had been picked out.

He survived Kolyma but lost all his teeth, his jaw was broken and he may have suffered a heart attack. He was, as his biographer James Harford says, just another "egregious example of the incredible stupidity, not to speak of callous cruelty, of the purges of Joseph Stalin". More than five million Soviet men and women were arrested and either shot, jailed or sent to the Gulags during the Great Purge that was unleashed in the 30s.

After five months, Korolev was released from Kolyma – probably because Tupolev intervened on his behalf – and he spent the next five years in jail in Moscow working, officially, on aircraft and rocket design with other imprisoned engineers. Then, in 1945, he was made a colonel in the Red Army and sent to Germany. It was a remarkable change in his fortunes and it occurred for a simple reason: the Russians had captured Nazi stores of V2 rocket components and wanted to use them to develop their own missile system. Korolev's credentials were ideal.

The V2's guidance systems, turbo-pumps and engines were of startling sophistication, Korolev realised. However, the rocket's designer, Werner von Braun, and his team had defected to the Americans, with several complete V2s. This gave the US a huge advantage in the race to develop missiles from the Nazis' technology. But Korolev was a gifted engineer and designer – and an obsessive worker. "I can never forget, on going home, if there is something wrong with a technique," he told a colleague. He slept for only a few hours a night, lived frugally and on 21 August 1957 launched the Soviet R-7 rocket, the world's first intercontinental ballistic missile, on a 4,000-mile journey from Baikonur cosmodrome, in modern-day Kazakhstan, to the Kamchatka peninsula. He had beaten the USA by 15 months.

"His ability to inspire large teams, as well as individuals, is proverbial," says Harford in Korolev: How One Man Masterminded the Soviet Drive to Beat America to the Moon . "He had a roaring temper, was prone to shout and use expletives, but was quick to forgive and forget. His consuming passion was work, work, work for space exploration and for the defence of his country. One wonders how he maintained such an unswerving loyalty to a system that had treated him so cruelly."

Von Braun may have built the V2 and later the Saturn V rocket that took Armstrong and Aldrin to the moon, but his achievements were dwarfed by those of Korolev. The chief designer – he was never named in state communiqués because of official disapproval of "the cult of personalities" – developed the first intercontinental missile and then launched the world's first satellite, Sputnik 1. He also put into space the first dog, the first two-man crew, the first woman, the first three-man crew; directed the first walk in space; created the first Soviet spy satellite and communication satellite; built mighty launch vehicles and flew spacecraft towards the moon, Venus and Mars – and all on a shoestring budget.

However, it was the launch of the first man into space that truly marked out Korolev – and Gagarin – for greatness.

Yuri Gagarin was born on 9 March 1934, in Klushino, in the Smolensk region, 100 miles west of Moscow. His father and mother worked on the local collective farm, he as a storeman, she with a dairy herd, according to Jamie Doran and Piers Bizony in their book Starman: The Truth behind the Legend of Yuri Gagarin . In October 1942, the village was overrun by retreating German troops. The Gagarins were thrown out of their home and had to dig a shelter to survive the winter. Later Yuri's brother Valentin and sister Zoya were deported to labour camps in Poland.

Remarkably the family survived and in 1950 Yuri was sent to Moscow to train as a steel foundryman before enrolling in the newly built technical school in Saratov, where he took up flying, eventually becoming a military pilot. He was stationed in Murmansk and flew MiG-15 jets on reconnaissance missions.

In October 1959, a set of recruiting teams began visiting air bases across the Soviet Union. Nothing was said about the nature of their mission. In any case, most pilots failed the tests they were set. A privileged few, including Gagarin, were selected and sent to Burdenko military hospital in Moscow where the pilot recalled being examined, intensely, by groups of doctors. "They tapped our bodies with hammers, twisted us about on special devices and checked the vestibular organs in our ears," Gagarin recalled. "They tested us from head to toe."

Korolev – who had already stunned the world with the launch of Sputnik 1, the first satellite – was now preparing for his ultimate achievement: putting a human in space. After his earlier experiment with the ill-fated Laika, he had successfully flown a dog into orbit and returned it safely to Earth. And if a dog could do it, it was surely time for a human. However, at the time, doctors – both in the east and the west – were unsure about how the human frame would respond to the intense forces of launch and then the weightlessness of orbit. Hence their obsession with astronauts' fitness. In the end, 20 pilots were selected – only for them to find that the early version of the Vostok capsule that Korolev had come up with was so cramped, only those under 5ft 6in could get in it. The slightly built Gagarin fitted in nicely. Many of the others did not.

In the end, only Gherman Titov provided real competition for Gagarin. He was a brilliant pilot, intense, self-possessed and, as befits a teacher's son, was well-educated and fond of quoting poetry. A week before Vostok's lift-off, the choice was whittled down to the two of them.

Titov was convinced he would win but days before launch was told it would be Gagarin who would be going. Titov never got over being the second, largely unremembered man in space – he flew Vostok 2 on 6 August 1961 – and in 1998, shortly before his death, he still spoke bitterly about his rival: "Some people will tell you I gave him a hug [when his selection was announced]. Nonsense. There was none of that."

Behind the scenes, powerful forces had been backing Gagarin. Khrushchev knew spaceflight was a potent propaganda weapon. "Khrushchev and Gagarin were both peasant farmers' sons while Titov was middle-class," argue Bizony and Doran. "If Gagarin could reach the greatest heights, then Khrushchev's rise to power from similarly humble origins was validated."

So it was the peasant workers' son who headed for glory on the morning of 12 April 1961. He took the bus to the launch pad with Titov in tow – just in case there was a last-minute emergency. Both were wearing spacesuits. Then Gagarin stood up to go. "According to Russian tradition, one should kiss the person going away three times on alternating cheeks," cameraman Vladimir Suvorov recalled. "But they were wearing spacesuits with helmets attached, so they simply clanged against each other."

Gagarin squirmed into his capsule and waited. There was no countdown – a silly, American affectation according to Korolev who, at 9.06am, simply pressed an ignition key and the R-7 rose slowly from the pad. Gagarin shouted: " Poyekhali !" ("Let's go!")

"After the launch, there was complete silence in mission control apart from an operator repeating, every 30 seconds, that 'the flight is normal'," recalls Mikhail Marov, one of Korolev's research engineers. "Then he announced the ship had reached orbit and there was huge shout of joy." Marov – a fellow of the Russian Academy of Science who subsequently headed several space missions – today remembers Gagarin's talking quietly and calmly. "I can see clouds. I can see everything. It's beautiful," he told mission control. Around 9.50 Vostok began its sweep over America. Half an hour later its engine was retrofired and the capsule began its descent. Every manoeuvre had been controlled by Korolev from the ground.

"Those minutes seemed like eternity," Marov recalls. Then it was announced that Gagarin had landed safely. The Soviet press agency Tass immediately broadcast details of the flight and within minutes, crowds began to fill the streets of Moscow. "They looked like surging seas," says Marov. "I have never seen such enthusiasm of ordinary people. They took Gagarin's triumph as a personal victory."

In fact, his flight came perilously close to being a personal loss. As it began its descent, Gagarin's capsule should have separated from the main spaceship but a cable did not detach. The capsule began to spin and tumble "like a yo-yo" as one engineer later described it, exposing unprotected areas to the searing heat of re-entry. The temperature inside rose dangerously. "I was in a cloud of fire rushing toward Earth," Gagarin recalled. Ten minutes later the errant cable burned through; the two modules separated; and Gagarin's capsule ceased its wild rotation. The cosmonaut, who had nearly lost consciousness, blew open its hatch and was ejected, as planned, to make a parachute descent. He landed close to the village of Smelovka, near Saratov in southern Russia. "I saw a woman and a little girl coming toward me. I began to wave my arms and yell. I said I was a Soviet and had come from space."

News of Gagarin's flight swept round the globe. "Man in space!" the London Evening News announced that day while the following morning's Guardian proclaimed: "Russia hails Columbus of space: World's first astronaut home safely." In the US, which had its own space ambitions, the news was less welcome. Reporters pressed Nasa for a quote and phoned press officer John "Shorty" Powers at 4.30am. Powers, outraged at the call, snarled: "What is this! We're all asleep down here!" Next morning's US headlines included the classic: "Soviets put man in space. Spokesman says US asleep."

Powers wasn't far wrong, of course. At the time, Nasa was preparing its own manned Mercury missions but had got no further than a 17-minute test-flight with a chimp called Ham. Korolev had beaten the USA easily. "He seemed to be able to play these little games with his adversaries at will," says Tom Wolfe in The Right Stuff . "There was the eerie feeling that he would continue to let Nasa struggle furiously to catch up – and then launch some startling new demonstration of how just how far ahead he really was." One newspaper cartoon even showed a chimpanzee telling another: "We are a little behind the Russians and a little ahead of the Americans."

Hugo Young, writing in the Times , was more straightforward. "Gagarin's triumph pitilessly mocked the image of dynamism which President Kennedy had offered the American people. It had to be avenged almost as much for his sake as for the nation's." So Kennedy wrote a memo demanding that a space programme be found that promised dramatic results and that the United States could win. The crucial words were "dramatic" and "win". Only a manned lunar landing filled those criteria.

Thus, on 25 May 1961 – a few weeks after Gagarin's flight – Kennedy made his speech committing the United States to sending a man to the moon and returning him safely before the end of the decade. The Space Race was on. "That speech, that reaction needs to be understood as a key part of the fight of Yuri Gagarin because his mission was the immediate stimulus for the landing of Neil Armstrong and Buzz Aldrin ," says space expert Professor John Logsdon of George Washington University.

Few observers gave America much chance of victory. The Soviet programme looked unbeatable with Gagarin and Korolev as its face and brains. It was not to be, however. Korolev was living on borrowed time. He had already suffered one heart attack and was now succumbing slowly to illnesses brought on by his treatment in the Gulag. "People thought of him as a burly man, built like a bear, but the truth was that his body was made rigid by countless ancient injuries," say Doran and Bizony. "He could not turn his neck, but had to swivel his upper torso to look people in the eye; nor could he open his jaws wide enough to laugh out loud."

On 5 January 1966, Korolev was admitted to hospital for what was supposed to be routine surgery. But during the operation, on 14 January, he haemorrhaged on the operating table. Doctors tried to put a tube into his lungs to keep him breathing but found his jaw had been broken so badly in the Gulag, they couldn't pass it through his damaged throat. He never regained consciousness and died, aged 59, later that day. For the first time, the Soviet people learned who the chief designer was. Pravda ran a two-page obituary and Korolev was given a state funeral. Thousands gathered as his ashes were carried through Red Square to the Kremlin Wall. Gagarin gave the final eulogy.

Korolev's little eagle only survived his mentor by two years. On 27 March, Gagarin took off from Chkalovsky airbase on a MiG-15UTI jet with fellow pilot Vladimir Seryogin. It crashed a few minutes later, killing both men. A KGB investigation suggested that a near-miss with another jet had sent Gagarin's plane spinning out of control, though the cause of the accident remains unclear and the subject of unending conspiracy theories. On 4 April 1968 – after a huge state funeral in which tens of thousands gathered – Gagarin's ashes were interred close to Korolev's. The Soviet space programme had been orphaned.

Before his death, Korolev had designed a mighty launcher, the N1, which was intended to carry men to the moon. Engineers continued to work on it but without the chief designer's guidance and inspiration, they were lost. In 1969, just as America was perfecting its Apollo missions, two unmanned test N1 launches were carried out. The first exploded in flight. The second didn't even make it off the launch pad. "The rocket fell over, destroying the entire launch complex," says Harford. The Soviet lunar dream was over. Weeks later, Armstrong and Aldrin were walking on the moon.

The might of the US aerospace industry had prevailed and America emerged as winners of the space race, though there is an ironic coda to this story, one that Korolev would have certainly enjoyed. After Apollo, the US went on to develop the space shuttle, the world's first reusable spacecraft, which was used – among many tasks – to construct the international space station. By the 1980s, the US was flaunting its space prowess. Then things went badly awry. Two shuttle accidents caused the deaths of 14 astronauts. As a result, the craft will be grounded later this year.

And after that, there will be only one way to get astronauts – no matter what their nationality – to the space station: on a Russian Soyuz launcher, a rocket derived from the R-7 that Korolev designed to put Gagarin into space. As Logsdon says: "The rocket we now rely on to put humans into space is essentially the same launch vehicle, taking off from the same launch pad, that was built by Korolev and which took Gagarin into space. Half a century later, we are back where we started. It raises the question of whether or not the world is serious about human spaceflight."

It also demonstrates, starkly, the enduring genius of Sergei Pavlovich Korolev, the man who launched Yuri Gagarin.

- The Observer

- Yuri Gagarin

- South and central Asia

- Buzz Aldrin

First orbit tracks gagarin's historic space flight - video.

Russian cosmonaut Yuri Gagarin to be honoured with statue in London

Yuri Gagarin - in pictures

Comments (…), most viewed.

- Biographies & Memoirs

Enjoy fast, free delivery, exclusive deals, and award-winning movies & TV shows with Prime Try Prime and start saving today with fast, free delivery

Amazon Prime includes:

Fast, FREE Delivery is available to Prime members. To join, select "Try Amazon Prime and start saving today with Fast, FREE Delivery" below the Add to Cart button.

- Cardmembers earn 5% Back at Amazon.com with a Prime Credit Card.

- Unlimited Free Two-Day Delivery

- Streaming of thousands of movies and TV shows with limited ads on Prime Video.

- A Kindle book to borrow for free each month - with no due dates

- Listen to over 2 million songs and hundreds of playlists

- Unlimited photo storage with anywhere access

Important: Your credit card will NOT be charged when you start your free trial or if you cancel during the trial period. If you're happy with Amazon Prime, do nothing. At the end of the free trial, your membership will automatically upgrade to a monthly membership.

Buy new: .savingPriceOverride { color:#CC0C39!important; font-weight: 300!important; } .reinventMobileHeaderPrice { font-weight: 400; } #apex_offerDisplay_mobile_feature_div .reinventPriceSavingsPercentageMargin, #apex_offerDisplay_mobile_feature_div .reinventPricePriceToPayMargin { margin-right: 4px; } -47% $15.97 $ 15 . 97 FREE delivery Monday, May 6 on orders shipped by Amazon over $35 Ships from: Amazon Sold by: OTTNOT

Return this item for free.

Free returns are available for the shipping address you chose. You can return the item for any reason in new and unused condition: no shipping charges

- Go to your orders and start the return

- Select the return method

Save with Used - Good .savingPriceOverride { color:#CC0C39!important; font-weight: 300!important; } .reinventMobileHeaderPrice { font-weight: 400; } #apex_offerDisplay_mobile_feature_div .reinventPriceSavingsPercentageMargin, #apex_offerDisplay_mobile_feature_div .reinventPricePriceToPayMargin { margin-right: 4px; } $11.50 $ 11 . 50 FREE delivery Monday, May 6 on orders shipped by Amazon over $35 Ships from: Amazon Sold by: Books Today For You

Download the free Kindle app and start reading Kindle books instantly on your smartphone, tablet, or computer - no Kindle device required .

Read instantly on your browser with Kindle for Web.

Using your mobile phone camera - scan the code below and download the Kindle app.

Image Unavailable

- To view this video download Flash Player

Follow the author

Beyond: The Astonishing Story of the First Human to Leave Our Planet and Journey into Space Hardcover – April 13, 2021

Purchase options and add-ons.

“This remarkable account of the 1961 race into space is a thrilling piece of storytelling. . . . It is high definition history: tight, thrilling and beautifully researched.”— The Times, London, Front Page Lead Review

“ Beyond has the exhilaration of a fine thriller, but it is vividly embedded in the historic tensions of the Cold War, and peopled by men and women brought sympathetically, and sometimes tragically, to life.”—Colin Thubron, author of Shadow of the Silk Road

09.07 am. April 12, 1961. A top secret rocket site in the USSR. A young Russian sits inside a tiny capsule on top of the Soviet Union’s most powerful intercontinental ballistic missile—originally designed to carry a nuclear warhead—and blasts into the skies. His name is Yuri Gagarin. And he is about to make history.

Travelling at almost 18,000 miles per hour—ten times faster than a rifle bullet—Gagarin circles the globe in just 106 minutes. From his windows he sees the earth as nobody has before, crossing a sunset and a sunrise, crossing oceans and continents, witnessing its beauty and its fragility. While his launch begins in total secrecy, within hours of his landing he has become a world celebrity – the first human to leave the planet.

Beyond tells the thrilling story behind that epic flight on its 60th anniversary. It happened at the height of the Cold War as the US and USSR confronted each other across an Iron Curtain. Both superpowers took enormous risks to get a man into space first, the Americans in the full glare of the media, the Soviets under deep cover. Both trained their teams of astronauts to the edges of the endurable. In the end the race between them would come down to the wire.

Drawing on extensive original research and the vivid testimony of eyewitnesses, many of whom have never spoken before, Stephen Walker unpacks secrets that were hidden for decades and takes the reader into the drama of one of humanity’s greatest adventures – to the scientists, engineers and political leaders on both sides, and above all to the American astronauts and their Soviet rivals battling for supremacy in the heavens.

- Print length 512 pages

- Language English

- Publisher Harper

- Publication date April 13, 2021

- Dimensions 6 x 1.49 x 9 inches

- ISBN-10 0062978152

- ISBN-13 978-0062978158

- See all details

Frequently bought together

Similar items that may deliver to you quickly

From the Publisher

Editorial Reviews

“Dramatic and dynamic. Stephen Walker’s passion for his subject along with his exceptional research and attention to detail have brought my father’s extraordinary journey vividly to life.” — Elena Gagarina, daughter of Yuri Gagarin

“ A spellbinding and completely authoritative account of Gagarin’s unexpected journey to immortality, this masterful book had me enthralled from the outset. A guaranteed gem.” — Colin Burgess, author of Freedom 7: The Historic Flight of Alan B. Shepard

“Exciting, well researched, and fascinating. I loved every word.” — Laura Shepard Churchley, daughter of Alan Shepard, America's first astronaut

“ Beyond brings to life the space race and the extraordinary story of Yuri Gagarin. Using first-hand testimony, Walker evokes the personalities, the science and the atmosphere of the time in a history that reads like a thriller ." — Anne Applebaum, author of Twilight of Democracy

“Vivid. . . .Dramatic. . . .This entertaining and carefully researched history achieves liftoff.” — Publishers Weekly

“This remarkable account of the 1961 race into space is a thrilling piece of storytelling….It is high definition history: tight, thrilling and beautifully researched.” — Sunday Times (London)

“Energetic history of the first years of the space race, focusing on Soviet cosmonaut Yuri Gagarin (1934-1968)… A welcome addition to the literature of space exploration.” — Kirkus Reviews

“A thrilling account of the first manned space flight…A great introduction to the gripping tale of Gagarin’s flight and its impact on space exploration history.” — Library Journal

"A fine tale...told with verve and suspense...A cliffhanger." — Wall Street Journal

"Scintillating...The thrilling ride to be the first man in space is vividly captured here." — Financial Times

About the Author

Stephen Walker was born in London. He has a BA in History from Oxford and an MA in the History of Science from Harvard. His previous book was Shockwave: Countdown to Hiroshima, a New York Times bestseller. As well as being a writer he is also an award-winning documentary director. His films have won an Emmy, a BAFTA and the Rose d’Or, Europe’s most prestigious documentary award.

Product details

- Publisher : Harper (April 13, 2021)

- Language : English

- Hardcover : 512 pages

- ISBN-10 : 0062978152

- ISBN-13 : 978-0062978158

- Item Weight : 1.54 pounds

- Dimensions : 6 x 1.49 x 9 inches

- #395 in Aeronautics & Astronautics (Books)

- #729 in Astrophysics & Space Science (Books)

- #1,044 in Scientist Biographies

About the author

Stephen walker.

Discover more of the author’s books, see similar authors, read author blogs and more

Customer reviews

Customer Reviews, including Product Star Ratings help customers to learn more about the product and decide whether it is the right product for them.

To calculate the overall star rating and percentage breakdown by star, we don’t use a simple average. Instead, our system considers things like how recent a review is and if the reviewer bought the item on Amazon. It also analyzed reviews to verify trustworthiness.

Reviews with images

- Sort reviews by Top reviews Most recent Top reviews

Top reviews from the United States

There was a problem filtering reviews right now. please try again later..

Top reviews from other countries

- Amazon Newsletter

- About Amazon

- Accessibility

- Sustainability

- Press Center

- Investor Relations

- Amazon Devices

- Amazon Science

- Sell on Amazon

- Sell apps on Amazon

- Supply to Amazon

- Protect & Build Your Brand

- Become an Affiliate

- Become a Delivery Driver

- Start a Package Delivery Business

- Advertise Your Products

- Self-Publish with Us

- Become an Amazon Hub Partner

- › See More Ways to Make Money

- Amazon Visa

- Amazon Store Card

- Amazon Secured Card

- Amazon Business Card

- Shop with Points

- Credit Card Marketplace

- Reload Your Balance

- Amazon Currency Converter

- Your Account

- Your Orders

- Shipping Rates & Policies

- Amazon Prime

- Returns & Replacements

- Manage Your Content and Devices

- Recalls and Product Safety Alerts

- Conditions of Use

- Privacy Notice

- Consumer Health Data Privacy Disclosure

- Your Ads Privacy Choices

It’s been 60 years since Yuri Gagarin became the first man in outer space

- By Daniel Ofman

Soviet cosmonaut Major Yuri Gagarin, first man to orbit the earth, is shown in his space suit. Photo undated.

Sixty years ago on Monday, the Earth sent its first human into outer space — Russia’s Yuri Gagarin.

On this day in 1961, Gagarin’s space capsule completed one orbit around Earth and returned home, marking a major milestone in the space race. As he took off, you could hear Gagarin’s muffled yet iconic “ Poehali, ” which means “Let’s go” in Russian.

Gagarin’s pioneering, single-orbit flight made him a hero in the Soviet Union and an international celebrity. After putting the world’s first satellite into orbit with the successful launch of Sputnik in October 1957, the Soviet space program rushed to secure its dominance over the United States by putting a man into space. Gagarin’s steely self-control was a key factor behind the success of his pioneering, 108-minute flight.

The World’s Marco Werman spoke to Stephen Walker, who has just published a book about Yuri Gagarin called “Beyond: The Astonishing Story of the First Human to Leave Our Planet and Journey into Space.”

Marco Werman: Stephen, tell us a little more about Yuri Gagarin. Before he became known as the first man in space, who was he?

Stephen Walker: Well, it’s a really interesting question. He was actually brought up in a little village just to the west of Moscow. And in 1941, Nazis invade Russia, and they swallow Gagarin’s village. And something very seminal happens to Gagarin, which I think determines, in some respects, the course of his life. At the age of 7, he is horrified to see that his little brother, Boris, age 5, is being hanged from an apple tree by an SS officer, and he tries to cut his brother down from this branch. But he’s very small. He can’t do it. So, he races back, yells at his mother, Anna, who comes racing out, rushes across and cuts down little Boris from this tree just in time. And that experience seared Gagarin for life. It gave him kind of an inner toughness and inner resilience, which is why he was able to sit effectively on top of the world’s biggest nuclear missile, waiting to be blasted into space.

Right. And as we know, the Americans were stunned when the space capsule orbited the Earth. So, I casually told the story of this day in 1961, earlier, basically the rocket launch; Gagarin went up, did an orbit and then came back down alive. But that doesn’t quite capture the intense drama of the day, does it?

Not at all. This rocket — it’s called an R-7 — is unbelievably dangerous. The chances of Yuri Gagarin getting back alive were less than 50-50. Almost everything you can think of goes wrong. No one knows what happens to a human being in space. And then, of course, the rocket itself is so dangerous because many of them have blown up. The Russians were desperate to get ahead of America, which means they took risks. So, it’s an incredibly dramatic tale of this 106 minutes that sort of changed the world.

What was the mission of the Soviet rocket and what did Gagarin himself think at the time about it?

Well, the mission was basically to see if a human being could survive in space and fly in orbit around the Earth. And there is this secret briefing given by Yuri Gagarin the day after his flight, and he tells the story of what happened 11 minutes after launch. Gagarin separated from the rest of his rocket, and he started very gently to spin. And then, he turned to the little porthole on his right and he saw the Earth. He had escaped the biosphere.

Incredible perspective. How was Gagarin received once he touched down some 90 minutes later?

Well, he actually landed hundreds of kilometers, of course. So, he ejects from this capsule at about 20,000 feet and the capsule lands separately. And Gagarin by parachute lands in a potato field. And there’s no one there except an old lady and her granddaughter who were picking potatoes. So, he goes up to them and they run away. They’re absolutely terrified. They see this, kind of, orange spacesuit. He manages to convince them he’s a comrade, he’s Soviet, he’s safe, and he says, “I need to get to a phone. Have you got any way of my getting to a phone?” So, they offer him the use of a horse. This guy’s been around the world at 18,000 miles an hour. And they’re talking about putting him on a horse to get to a telephone. It’s just crazy. Just before the horse arrives, some tractor drivers turn up, very curious. They’ve heard about him on the radio, on the kind of state radio, because it’s now being broadcast. And then within minutes, this jeep arrives with soldiers and they all start taking photographs. And there is a photograph of him, which is in my book, and it’s just wonderful. He’s just been around the whole planet and he’s landed in this potato field. And there’s this photograph. It’s quite extraordinary.

I mean, it speaks of the high ambition and also the low reality of the Soviet Union during the Cold War. The USSR, as you said, Stephen, was determined to beat the US in getting a human into space. What was the reaction in the West when Yuri Gagarin went up and came home, and specifically in the United States?

Absolute shock. I mean, there is a press conference which President Kennedy, remember new in the job, gave that afternoon, and he looks completely and utterly shell shocked. He says he extends his congratulations to Khrushchev, who was the premier of the USSR at the time and also to the man who was involved. He can’t even say his name, but it is a real bad moment for him and for the American space program. You’re looking at somebody who is on the back foot. And we know this because two days later, Gagarin was celebrated in a, basically, parade that was millions of people, the biggest party really in Moscow’s history.

And at the very time that Gagarin was being celebrated and having the hero of the Soviet Union gold star medal pinned to his chest, we know that Kennedy was in the Cabinet Room at the White House with his advisers, and Kennedy is tapping his teeth with his pencil, which is always a sign of nervousness with him. And he says, “What can we do? What can we do to catch up? How do we leapfrog them?” And he comes up with a wonderful line. He says, “Even if the janitor in the White House has an answer, I want to hear that answer.” And this is when the moon idea really starts to take hold. And what I hope I have managed to do is to put readers right in the center, in the epicenter, of events, the little fly on the wall, that gives us an often very jaundiced view, but really fascinating inside story of what was really happening and how different that was from the presentation to the world of what was happening.

This interview has been lightly edited and condensed for clarity.

The article you just read is free because dedicated readers and listeners like you chose to support our nonprofit newsroom. Our team works tirelessly to ensure you hear the latest in international, human-centered reporting every weekday. But our work would not be possible without you. We need your help.

Make a gift today to help us reach our $25,000 goal and keep The World going strong. Every gift will get us one step closer.

NOW AVAILABLE IN PAPERBACK, ORDER YOUR COPY Here.

“a thrilling piece of storytelling” the sunday times, 12 april 1961.

“Always thrilling … brings a huge amount that is fresh and new to our understanding of the Space Race.”

Daily telegraph, explore humanity’s greatest adventure.

Twenty-seven-years old, a loyal communist and father of two, Yuri Gagarin blasts into the skies inside a tiny cannonball-shaped capsule at the top of a modified Soviet R-7 missile – replacing the nuclear warhead it was originally designed for.

“The most gripping, exciting and intense book I have read in the year that I have been interviewing writers on this show. Just a wonderful book, I can't recommend it enough."

The darkest days of the cold war. the usa and ussr confront each other across an iron curtain. their new battleground is space., two teams are training towards that goal, in the us there are seven astronauts, in the ussr there are twenty cosmonauts, two teams are training towards that goal, in the usa there are seven astronauts.

AND The race will come down to the wire

“Exciting and fascinating. I loved every word."

“ beyond has the exhilaration of a fine thriller - brought sympathetically, and sometimes tragically, to life.", "an exhilarating journey into space. beyond is a dramatic tour de force.", “vivid... dramatic. this entertaining history achieves lift off.", “gripping, rich in novelistic detail… highly recommended.”, “outstanding”, "cinematic.", the spectator, "scintillating.", financial times, discover the inside story of the event that shook the world.

"This book is a triumph."

Beyond is available to order today.

ALSO AVAILABLE AT BOOKSHOP.ORG , SUPPORTING INDEPENDENT BOOKSHOPS.

- TN Navbharat

- Times Drive

- ET Now Swadesh

technology science

10 Key Facts About Yuri Gagarin - The First Man In Space

Updated Jan 4, 2024, 14:50 IST

Yuri Gagarin, Soviet cosmonaut who became the first man to travel into space. (Image Credit: NASA)

Chelsea NYC Shooting: Man Hurt In Officer Involved Gunfire On West 24th Street | All You Need To Know

'Young Kit': How Wildlife Fan's Kindness Turned Fox Into a Furry Friend

Charlotte Shooting Victims: All About Thomas Weeks Jr, Joshua Eyer, Sam Poloche and Alden Elliott

Asteroid Hits Earth With Fastest Spin Ever; NASA Shares Shocking Details

Changpeng Zhao, Ex Binance CEO, Will Be The Richest Person In US Prison

Drake Dissed In Euphoria: Netizens Debate Who Did It Better Kanye West, Kendrick Lamar Or Nicki Minaj

Mayank Yadav Injured Again? LSG Speedster Leaves Field Without Completing Spell During IPL 2024 Match vs MI

Horoscope Today: Astrological Predictions on May 1, 2024, for all Zodiac Signs

Google Bans Two Android Apps From Play Store; Here Is Why

iPhone 16 Camera Design Leaked: What To Expect From Apple This September

iPhone 16 Pro Max Design Leaks Online, Here Is Everything You Need To know

OnePlus 12T Price, Launch Date In India, Specifications And More: Check Latest Leaks Here

AIR & SPACE MAGAZINE

How yuri gagarin was picked to be first in space.

NASA had the Mercury Seven. The Soviets had the Vanguard Six.

Stephen Walker

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/8b/f0/8bf0f603-a68b-49aa-9678-8eb5210cb171/gagarin_before_flight.jpg)

Sixty years ago, early on the morning of April 12, 1961, Soviet air force pilot Yuri Gagarin launched from Kazakhstan on Vostok-1, narrowly beating out American Alan Shepard (by three weeks) to become the first person to travel beyond Earth’s atmosphere into the dark silence of space. Gagarin’s story gets a fresh look in Stephen Walker’s riveting and thoroughly researched new book Beyond , from which the following excerpt is taken.

DEEP IN A birch forest in the Shchyolkovsky District northeast of Moscow, far from the main highway to the city and hidden from prying eyes, stood a small, old-fashioned two-story building half-buried in the snow. Everywhere the snow lay on the ground, even more thickly than it did eight thousand kilometres away in Washington. It had piled on the building’s steeply pitched roof, on the overhanging porch of its front door, and on the tangled branches of the birch trees, accentuating the heavy silence of the forest.

Apart from its curious location, there was nothing especially remarkable about the building itself. Perhaps its very anonymity helped to disguise its true purpose. For this nondescript edifice sitting in the middle of the forest in fact housed one of the most secret institutions in the USSR. Its code name was Military Unit 26266, but it was also known by its initials TsPK or Tsentr Podgotovki Kosmonavtov: the Cosmonaut Training Centre. And it was here on this particular Wednesday, January 18, 1961—two days before President John F. Kennedy’s inauguration in Washington and the day before Alan Shepard’s selection as America’s first astronaut—that six men were competing to be the first cosmonaut of the Soviet Union, if not the world.

Like NASA’s Mercury Seven astronauts in Langley, Virginia, the six men were also sitting in a classroom. But the similarities ended there. They were all obviously younger than the Americans, in their twenties and not thirties. They were all wearing military uniforms, not the casual Ban-Lon shirts favored by the Mercury pilots. And, discounting Gus Grissom, they were all visibly shorter, short enough to fit inside the Vostok spherical capsule replacing the thermonuclear warhead on top of the R-7 missile that they all hoped one day soon to fly in space.

Unlike the Mercury Seven, the Soviet pilots were not expecting an imminent decision on who would fly first. Instead, they were sitting an examination. Later that afternoon they would each be interrogated by a committee responsible for their training. The same committee had already assessed their performance the previous day in a crude simulator of the Vostok capsule. This simulator, the only one in the USSR, was not located in the forest but in a palatial pre-revolutionary building in Zhukovsky on the opposite side of Moscow, codenamed LII and otherwise known as the Gromov Flight Research Institute. For up to fifty minutes, under the watchful eyes of their examiners, each of the six men had practised procedures in the mock-up of the Vostok’s cockpit on the second floor of what had once been a tuberculosis sanatorium under the jurisdiction of the People’s Commissariat for Labour.

The building in the birch forest where the men were now sitting their examinations was the first structure in what would become, over time, a vast, heavily guarded complex closed to the outside world and dedicated solely to the training of the USSR’s cosmonauts. In 1968 it would change its name to Zvyozdny Gorodok—Star City—but that was still far in the future. Until then the area itself was known as Green Village, a nod perhaps to the acres of trees that shrouded it. When the new Cosmonaut Training Centre was established on January 11, 1960, by order of the commander of the Soviet Air Force, Chief Marshal Konstantin Vershinin, Green Village was chosen as the best site for its construction. It had many advantages. It was shielded by its forest but not far from Moscow. It was also only a few kilometres from Chkalovsky air base, the largest military airfield in the Soviet Union. And it was close to OKB-1, the secret design and production plant at Kaliningrad where the Vostok capsules were being built.

The six men had been training for ten months since March 1960, although the classroom building had only been in use since June. They had also used other anonymous centres in Moscow and continued to do so. In years to come, many of them would move into specially built residential blocks in Star City, but in January 1961 they were living near the Chkalovsky air base in basic two-room apartments with their wives and children if they had them, or in even more basic bachelors’ quarters if they did not.