- Trip Reports

- Areas & Ranges

- Huts & Campgrounds

- Logistical Centers

- Fact Sheets

- Custom Objects

- Plans & Partners

- Compass Basics: An Introduction to Orientation and Navigation

- Images (15)

- Comments (30)

- Introduction

The basics of compass usage are surprisingly simple and can be mastered quickly; and once learned they will certainly become an invaluable skill for any hiker, mountaineer, back country skier or suchlike outdoor enthusiast. However, if you are anything like most of us, chances are you have been packing a compass around for years, on your outdoor adventures, without fully utilizing it. It’s probably time to change that, isn’t it? Essentially a compass is nothing more than a magnetized needle, floating in a liquid, and responding to the Earth’s magnetic field consequently revealing directions. Over time compass markers have added features which make compasses work more harmoniously with maps and also more beneficially as stand alone tools. Today, compasses can be classified as one of four types, namely: fixed-dial (the type that you find on a key chain, or that come out of a gum ball machine) , floating dial (the needle is an integrated part of the degree dial) , cruiser (professional grade instrument used by foresters) , and orienteering. For hiking, mountaineering, back country skiing, canoeing, hunting or the like, the orienteering type is the most sensible being accurate to within 2 degrees, not requiring a separate protractor nor map orientation, and being highly affordable. Hence forth, this article focuses solely on the orienteering compass .

- Orienteering Compass Parts

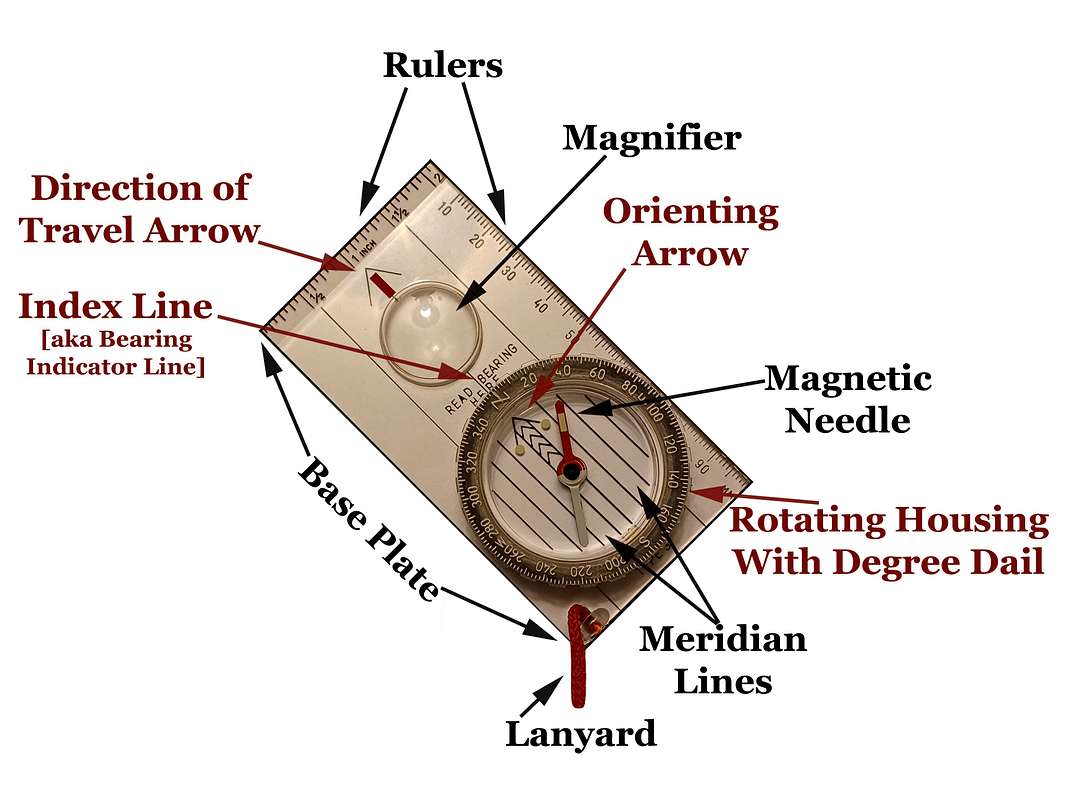

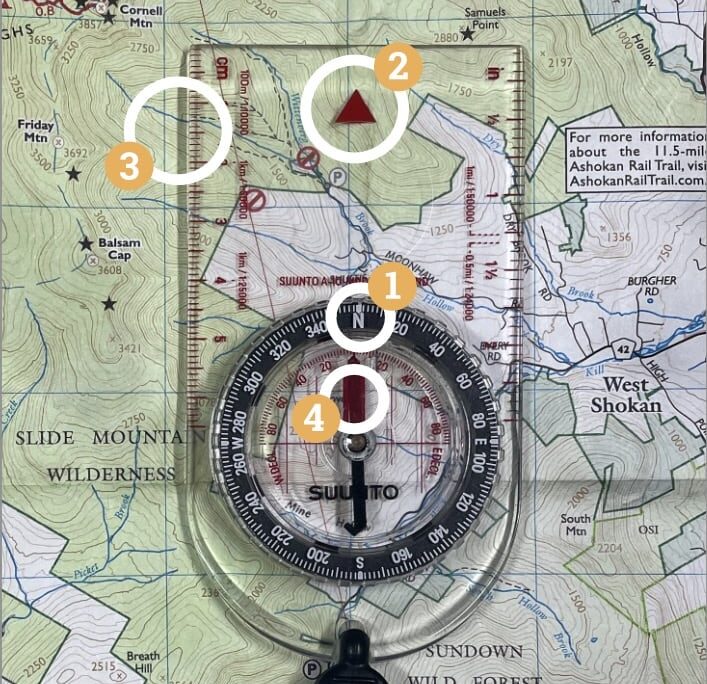

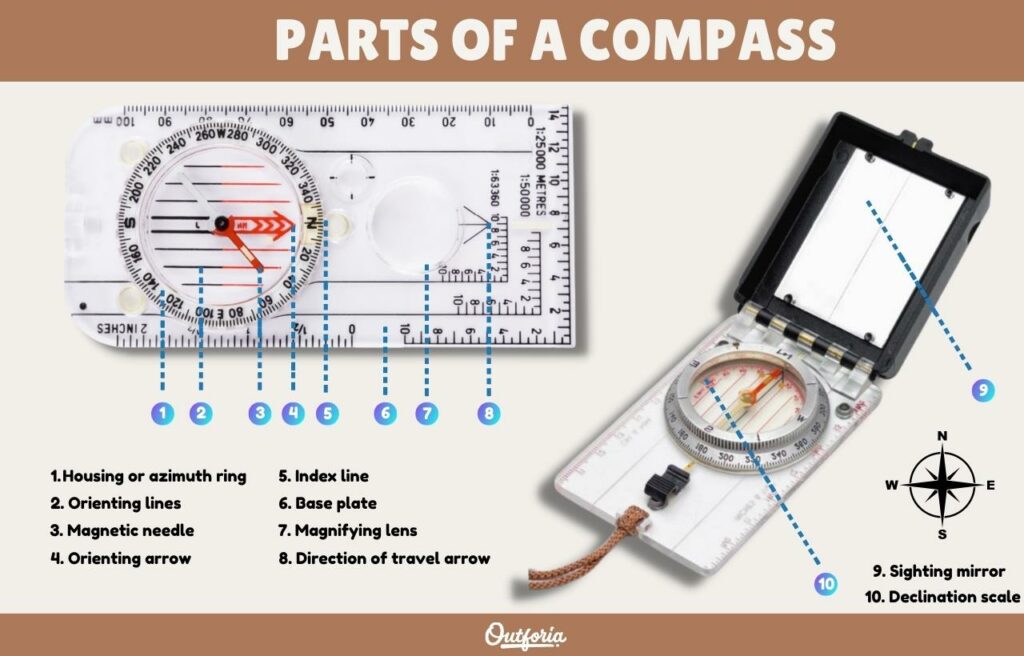

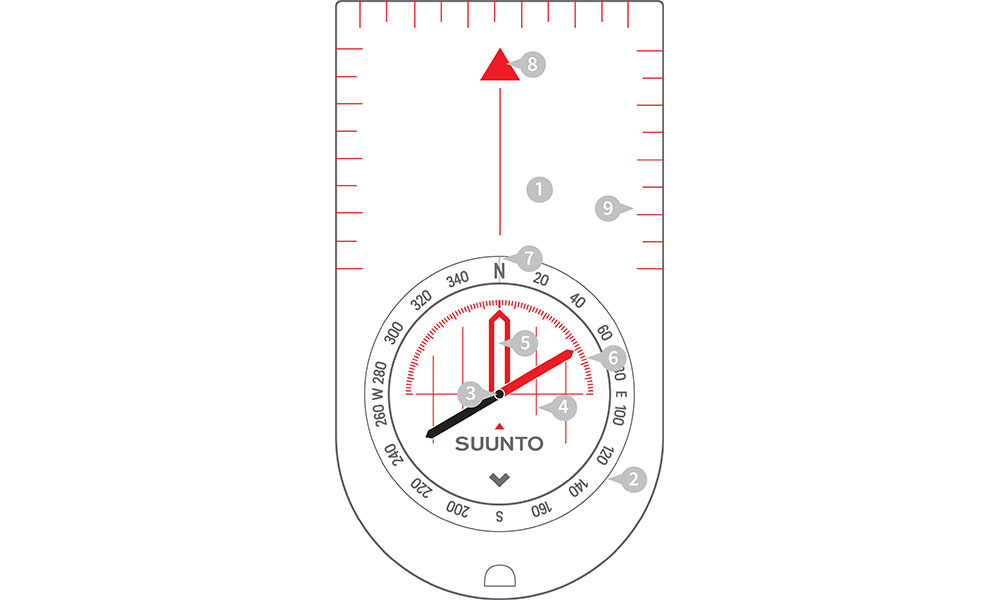

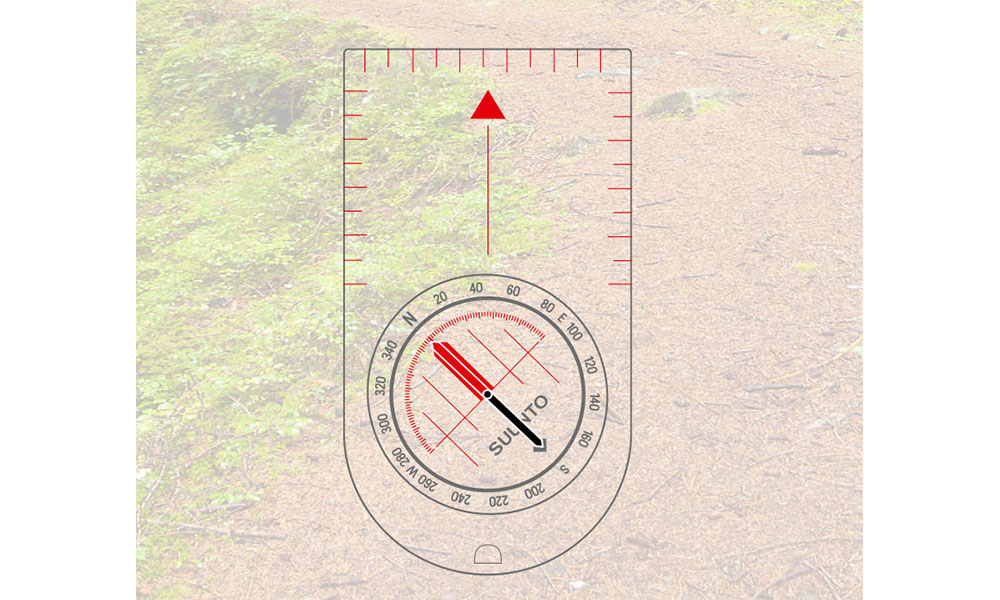

Let’s begin our introduction to compasses by taking a look at a standard, modern day, orienteering compass, and identifying its parts. As figure 1 shows an orienteering compass typically consists of three main parts: a magnetic needle, a revolving compass housing, and a transparent base plate. The magnetic needles north end is painted red and its south end white. The housing is marked with the four cardinal points of north, east, south, and west and further divided into 2 degree graduations indicating the full 360 degrees of a circle. The bottom of the rotating housing is marked with an orienting arrow, and meridian lines. The base plate is marked with a ruler (and/or USGS map scales), an index line (bearing reading line), as well as a direction of travel arrow.

- Directions and Degrees

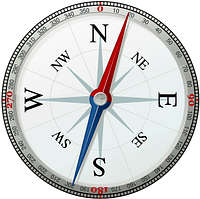

Before beginning to use a compass one should familiarize himself with basic directions and their degree readings. The four cardinal points are all 90 degrees apart, with East being at 90 degrees, South at 180 degrees, West at 270 degrees, and North at 360 degrees (or zero degrees). Identifying the degrees by 45 degree increments gives us the eight principal points of direction namely North (O or 360 degrees), North East (45 degrees), East (90 degrees), South East (135 degrees), South (180 degrees), South West (225 degrees), West (270 degrees), and North West (315 degrees). Memorizing the eight principal points can help one to instinctively associate directions and bearings, and help eliminate errors when taking bears (bearings are explained in the next section) . For example if you are told that a landmark is SE of your location, you know that is 135 degrees, or conversely if you know you need to go West but you calculate the bears as 90 degrees you will instinctively realize the bearing is wrong, as West is at 270 degrees (turn your compass around, you have committed the classic 180 degree error) . You may have heard directions given in terms like NNW or ESE, those types of directions are a result of distinguishing degrees in 22.5 degree increments resulting in the 16 traditional compass directions. Typically the eight principal points are sufficient to know. See figure 2.

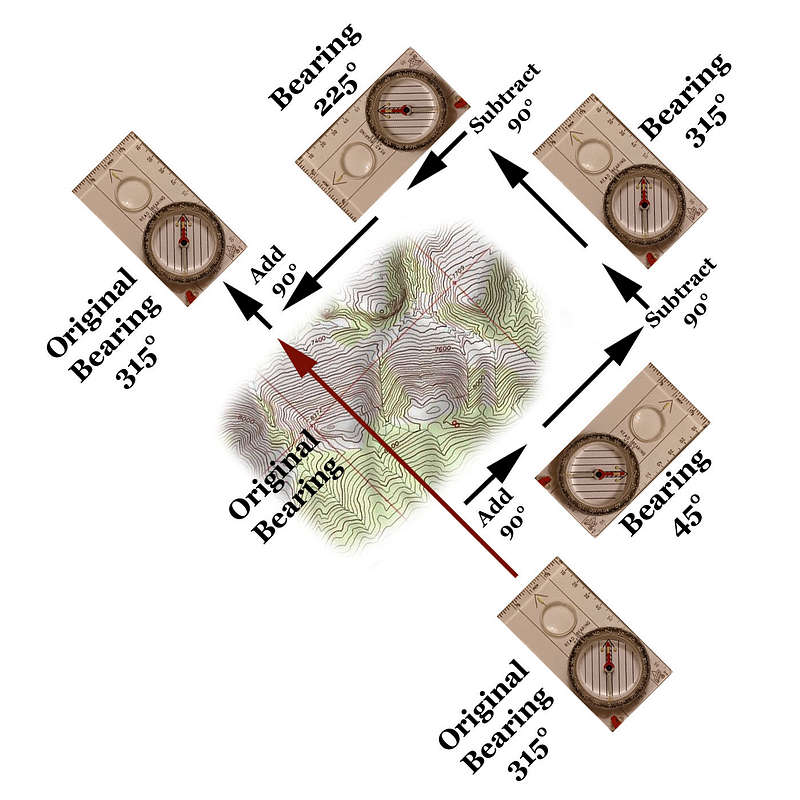

One of the most important uses of a compass is taking, and following a bearing. A bearing is the direction from one spot to another, measured in degrees, from the reference line of north; in other words it’s one of the 360 degrees of the compass rose. To take a bearing hold the compass in front of you with the direction of travel arrow pointing at the object of interest. Hold the compass level and steady, and rotate the housing dial, until the orienting arrow lines up with the red end (north end) of the magnetic needle, all the while keeping the direction of travel arrow pointed at the object. Read the number indicated at the index line, and that is your bearing. Now to follow that bearing to the object, let’s consider an example. Say you want to travel to a large rock outcropping on the horizon, which is currently visible to you, but which may leave your field of vision when you walk into a dip, or when pending clouds come in or the sun sets. Let’s say your bearing on the outcropping measured 315 degrees (or NW). Assuming you still have the direction of travel arrow pointing at the rock outcropping, and have not changed the 315 degree bearing setting on the dial, walk forward keeping the magnetic needle over the orienting arrow (by rotating your body, and not the dial), and the straight line course (as pointed out by the direction of travel arrow), will lead you to the rock outcropping. En route, when the rock outcropping leaves you line of sight pick out an intermediate landmark along the bearing, so you don’t have to constantly look down at your compass. Walk to the intermediate landmark, and repeat with another landmark until you reach your destination. Once you arrive at the rock outcropping, what bearing do you use to return to where you came from? Actually you don’t need any other bearing besides the 315 degrees already set on your compass. To return, just point the direction of travel arrow at you, instead of forward, and then rotate your body until the orienting arrow lines up with the red end (north end) of the magnetic needle, and then walk straight ahead while keeping the magnetic needle over the orienteering arrow (just as you did in going to the rock outcropping). That is the easy way to backtrack, of course you could also calculate your back bearing by subtracting 180 from your forward bearing of 315, and set the 135 degree (SE) difference at the compasses index line and then use the same body rotating method mention earlier, only this time you’d have the direction of travel arrow pointing your way. Try this. Take your compass to an empty parking lot or field and mark a spot. While standing at the spot set your compass to any bearing between 0 and 120 degrees, pick a landmark along the direction of travel and take 15 steps toward it. Stop, add 120 degrees to your initial bearing, pick out a landmark along that bearing and walk another 15 steps toward it, stop and once again increase your bearing by 120, pick out a third landmark and again walk 15 steps. Notice you have arrived back at your original starting location. Let’s return to the example above where we took a 315 degree (or NW) bearing on a rock outcropping, and lets suppose that enroute to the outcropping we encounter an obstacle which we must go around thus forcing us to deviate from our straight line course. If you are lucky enough to be able to pick out a landmark that’s along the bearing, and also on the other side of the obstacle, you have nothing to worry about, just go around the obstacle and get back on course by reaching the landmark and aligning the red end of the magnetic needle over the orienteering arrow, and continue walking.

If you can’t see a landmark along your course, there are a couple of other methods you can use to get around the obstacle and get back on your original course. One method is to have a member of your party navigate the obstacle, and then treat him like a landmark. One he has cleared the obstacle talk him into position along your original bearing. Also have him take a back bearing on you to confirm he is in indeed back on course. He can do this by pointing the direction of travel arrow of his compass at himself and then turning his body so as to align the red end of the magnetic needle over the orienteering arrow, and he should notice that you are along the bearing, if not he needs to move left or right. If the obstacle is too large for the previously described method, or you are on a solo trip, you can use right-angles to maneuver the obstacle. To do this turn 90 degrees and walk across the front of the obstacle while counting your steps. To make a 90 degree turn without changing the bearing setting on your compass, simply turn your body until the red end (north end) of the magnetic needle points at the West marking (to turn right) or East (to turn left), as opposed to the normal North marking. Once you’re past the front of the obstacle turn 90 degrees again, by rotating your body until the red end of the magnetic needle is over the orienting arrow, and walk past the obstacle. Once past the obstacle, turn 90 degrees for a third time (by pointing the red end of the magnetic need at the opposite marking or your first 90 degree turn), and walk the same number of steps you counted to get past the front of the obstacle. Once the steps are up, turn your body to align the magnetic needle back over the orienteering arrow (thus turning 90 degrees for a fourth and final time), and you will be back on course. See figure 3.

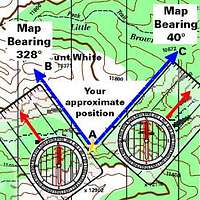

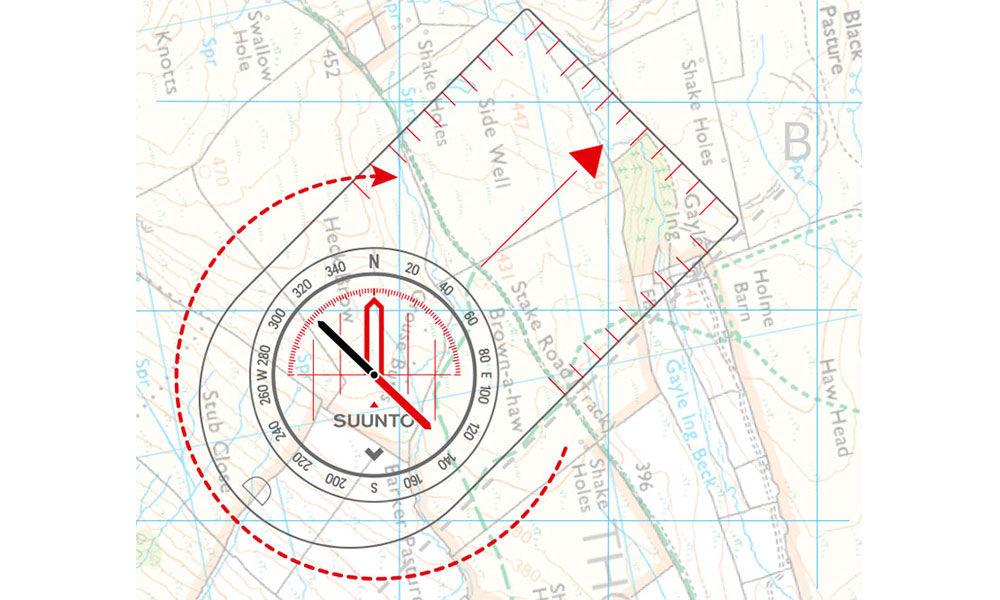

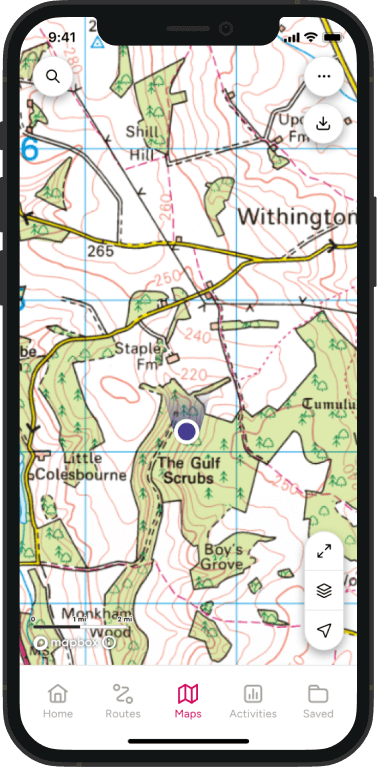

Bearings can also be calculated from a topographic map, and then used in the field. Assume you know you are at landmark A in the field, and you want to travel to landmark B, but you can’t see it. If you have a topographic map and you can identify both landmarks on the map, you can use you compass with the map to get a bearing thus enabling you to travel accurately to landmark B. On the map align either the left or the right edge of the base plate through landmarks A and B with the direction of travel arrow pointing toward B. If the base plate edge isn’t long enough to reach both landmarks simply extend it with any straight edge (for example a piece of paper), or draw a straight line between the points and align the compass edge with the line. Without moving the base plate turn the compass housing until the orienteering arrow points to the top of the map (remember that north is at the top of the map). If you are lucky enough to have one of the maps north/south grid lines visible under the compass housing you can align the meridian lines on you compass with the maps north/south grid line as you turn the housing until the orienteering arrow points to the top of the map. Now, read the bearing at the compasses index line, and follow the bearing in the field! See Figure 4A-C. A word of caution, map bearings and field bearings can differ in the USA by as much as 30 degrees east and 20 degrees west. This difference and how to deal with it is explained in the next section below on declination. Figure 4A-C, has a map with magnetic north lines, rather than true meridian lines, and so declination is not a factor.

- Declination

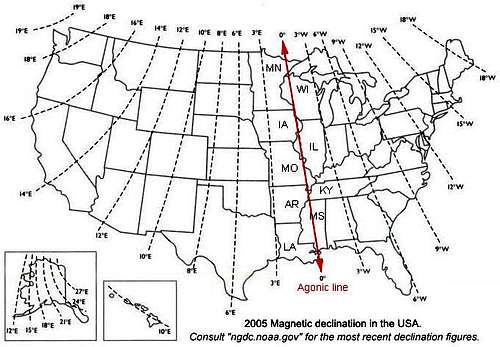

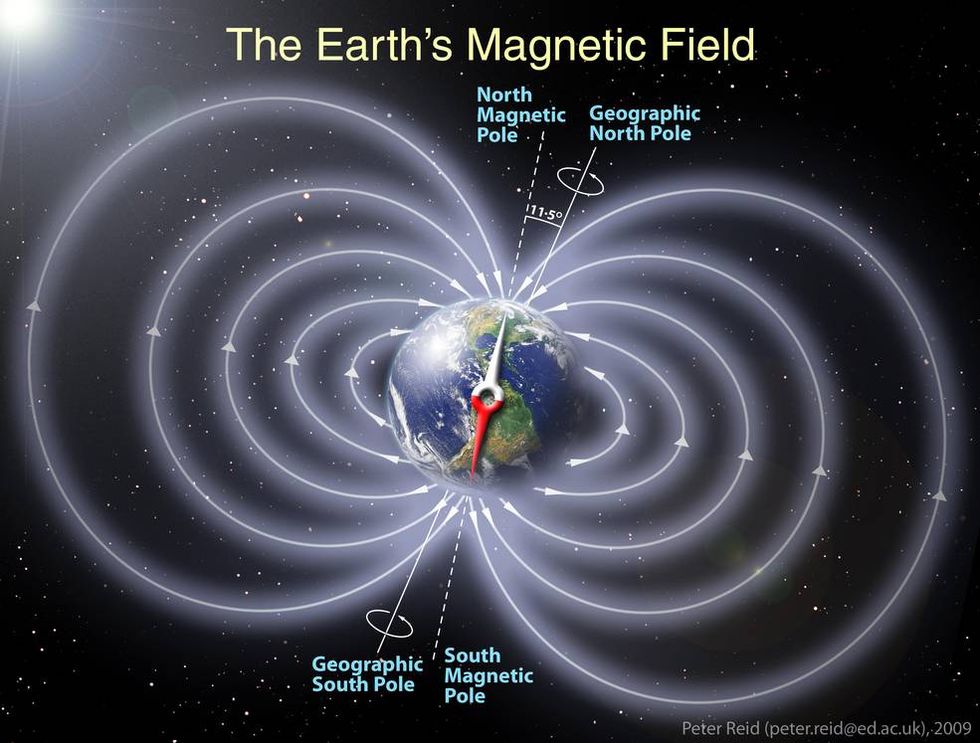

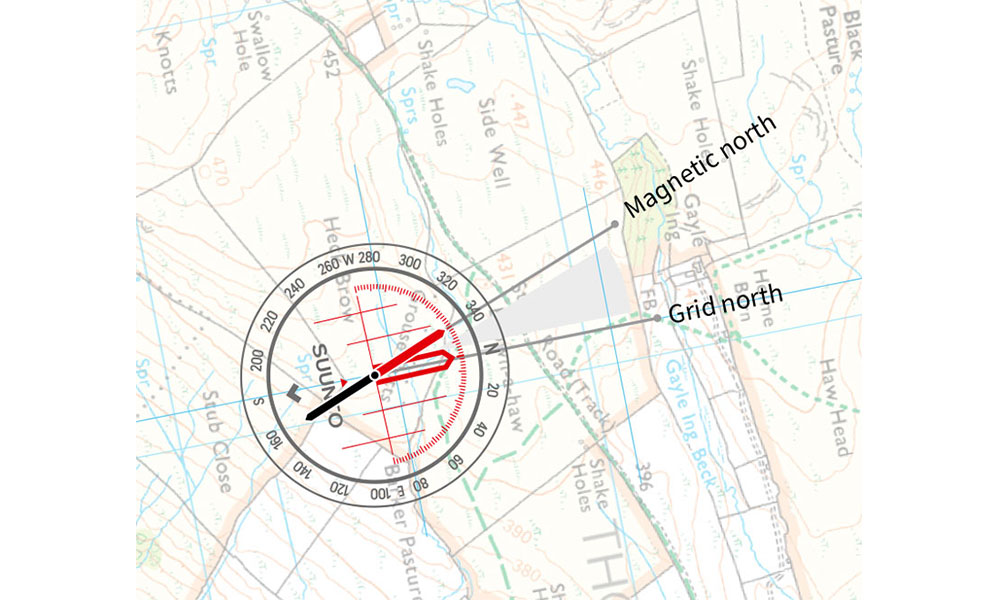

A compass needle is influenced by the earth’s magnetic field which causes it to line up with magnetic north. Maps, on the other hand, are typically oriented to the North Pole (which is truth north). The difference between these two norths is called declination, and must be accounted for when using your compass in conjunction with a map. There are places where the two norths are the same, these places fall on the so-called agonic line, see figure 5 . In areas to the left of the agonic line the magnetic compass needle points a certain number of degrees to the east of true north, and on the other side of the line the magnetic needle points a certain number of degrees to the west of true north (in other words the magnetic needle points toward the agonic line). We say areas to the left of the line have east declination and those to the right have west declination. Figure 5 shows the 2005 declinations in the USA. Note, declination numbers change over time as magnetic poles shift. Thus said it’s important to know how old the declination information on your map is before heading out into the field. Current declinations can be had at the NGDC website . The website also tells you by how much declination is changing per year. Note that easterly declinations are changing by a west amount (minutes), and westerly declinations are changing by an east amount, thus over time magnetic north is approaching true north. If you know by how many minutes on average the declination of your area is changing per year you can use that to update an out of date map figure. For example if you have a map from 1960, and you learn that the declination is changing by 0° 7' W/year, multiple that number by the elapsed years, and divide the result by 60 to get the degree change in declination. For example, (2007-1960) * 7 = 329; since there are 60 minutes in a degree 329/60 = 5.48 degrees or about 5.5 degrees. So if declination on the 1960 map is 15 degrees east, the 2007 value is 15-5.5 or 9.5 degrees east.

If you are simply taking and following bearings in the field, you can completely ignore declination. Likewise if you are only calculating and working with bearings on a map declination is unimportant. However, when you calculate map bearings from a map drawn to true north and then use the bearings in the field, you may be thrown completely off course if you don’t adjusting them for the declination of the area. Consider this, say you are in Rhode Island where the declination is 15 degrees west, and lets say your map bearing is 0 degrees (or directly north). You set your compass dial to zero, turn your body to align the magnetic needle over the orienteering arrow, and take off in the direction of the direction of travel arrow walking toward an intermediate landmark, without doing any bearing adjusts for declination . In doing so, for each 60 feet you travel, you will be 15 feet to the west of your course, thus after traveling one mile you will be one-quarter mile off course! Fortunately, it a simple matter of adding to or subtracting from a map bearing to compensate for declination. Also, modern compass are available which can be set to automatically adjust for declination if you don’t want to bother with the math, if so equipped consult your compass booklet to learn how to set it. Here is all you need to remember when converting a map bearing to a magnetic bearing for use in the field: If your declination is west (you are on the right side of the agonic line, see figure 5) , ADD the number of degrees of declination to your map bearings, and if your declination is east (you are on the left side of the agonic line, see figure 5) SUBTRACT the number of degrees of declination from your map bearing. Of course if you are plotting a field bearing on to a map do the opposite: that is ADD east declination to a magnetic (field) bearing and SUBTRACT west declination from a magnetic (field) bearing. Let’s say you are hiking in Utah where the declination is 13 degrees east. You take a bearing from you map and learn that your destination lays SE at 135 degrees. To use the bearing in the field you would subtract 13 (the declination) from 135 resulting in 122 and simply set your compass dial at 122 degrees and then follow that bearing to your destination. To get this clear in your mind, try this. Pretend your declination is 20 degrees east (your in Alaska). That means the needle on your compass is pointing 20 degrees east of true north. You need to travel due north (0 or 360 degrees), so set your compass to 360, hold it in front of you and turn your body until the magnetic needle aligns with the orienteering arrow. Think to yourself "my compass is pointing off by 20 degrees to the east, my right, so to go true north I really need to point my direction of travel arrow 20 degrees to my left" . So rotate you body counterclockwise until the magnetic needle lines up with the 20 degree marking on the compass housing dial. Now the direction of travel arrow is pointing to true north. Knowing where true north lies, now follow the declination adjustment rule by subtracting 20 east declination degrees from your 360 degree bearing and set your compass dial to 340 degrees. Again, turn your body until the magnetic needle aligns with the orienteering arrow, and notice the direction of travel arrow is now pointing to true north! So that is why you subtract east declination. To further cement this concept into your mind repeat this exercise, but use a pretend west declination instead. In field orienteering it’s all about getting the direction of travel arrow pointing in the correct direction. Some compasses have a declination scale marked within the housing. If you compass is so marked, you don’t need to adjust a map bearing before using it in the field, instead you just need to remember to align the magnetic needle with the declination marking rather than the orienteering arrow, and then follow the direction of travel arrow as usual. When you take a field bearing and want to plot it on a map, take it with the magnetic needle pointing to the declination figure rather than the orienting arrow, and then you can use the bearing on the map without adjustment. A map trick used to avoid converting a map bearing to a field bearing is to draw magnetic north lines on the map based off the diagram at the bottom center of all USGS maps. With magnetic north/south lines drawn you can then align the meridian lines of your compass dial with the hand draw lines and the bearings indicated at the index line are field ready bearings. Figure 4A-c above has magnetic north lines drawn on it, and thus no adjustment were needed to use the map bearing in the field. A compass trick used to avoid declination adjustments is to place a piece of scotch tape over the compass dial starting at the east declination and ending at the value of declination plus 180. Map bearings can then be set on the compass dial as read from the map, but the magnetic needle now needs to be aligned with the tape line, rather than the orienteering arrow. Note if the declination is west, place the tape strip at 360 minus declination to 360 minus declination minus 180. The mechanical declination adjustment on so-enabled compasses uses this very procedure.

- Compass Dip

As learned in the declination section, magnetic needles are affected by the horizontal direction of the Earth’s magnetic field. Bearing that in mind you might not find it surprising to learn that they are also affected by the vertical pull as well. You see, the closer you get to the magnetic north pole (located near Bathurst Island in Northern Canada in 2007), the more the north-seeking end of the needle is pulled downward. Whereas, at the south magnetic pole (located just off the coast of Wilkes Land, Antarctica in 2007) the north-seeking end of the needle is deflected upward. Only at the equator is the needle unaffected by vertical magnetic forces. To overcome magnetic dip manufacturers must design compasses that have the needle balanced for the geographic area in which they will be used. Thus, a compass built for use in North America, will not work in South America. The North American compass will have the pivot point the needle rests on slightly into the north half of the needle thus offsetting the downward pull. When the compass is taken to South America, the imbalance will work in the same direction as the vertical pull and the needle could very well rub against the roof of the housing making the compass unusable. In other words you will need a compasses manufactured for use in the part of the world you intend to use it. As a result of these magnetic variances, the compass industry has divided the earth into 5 "zones", which you can learn more about at thecompassstore.com . Compasses with so-called global needles are available, and they can be used accurately in any part of the world. Global needles are also useful if you tend to take bearings while moving making it difficult to hold the compass level. Global needle compasses can handle tilts up to 20 degrees.

- Triangulation

It was mentioned early that one of the most important uses of a compass is for taking and following bearings. Equally important is using a compass to pinpoint your exact location on a topographic map. If you can look at a map and determine a line you are on, such as a road, hiking trail, or mountain ridge, you can pinpoint your location with only one other piece of information. Say you are on a hiking trail, and to the west you can identify a mountain peak. You take a bearing on the peak and learn that is at 280 degrees. Next you adjust it for, say, the 10 degree easterly declination of the area arriving at a map bearing of 290 degrees - remember to convert a field bearing to a map bearing do the opposite conversion of a map bearing to a field bearing by adding east declination and subtracting west declination . Next, with the adjusted bearing set on the compass dial, find the landmark on the map, and point the direction of travel arrow in the direction of the landmark with the edge of the base plate on the landmark. Keeping the edge of the base plate on the landmark, rotate the base plate (not the dial) until the meridian lines of the compass align with the north/south lines of the map. Now plot this line back to the position line (in this case the hiking trail) you are known to be on, and where the line crosses the position line is your exact location. This method is known as free triangulation. If you are not on a position line, you will need to identify two landmarks in both the field and on the map to pinpoint your location. This method is known as triangulation. First take a bearing on landmark A, and adjust it to a map bearing and set that on the compass dial. Follow the above described process to orient the compass on the map by passing the base plate edge over the landmark and rotating the base plate (not the dial) until the meridian lines of the compass parallel the north/south lines on the map, and draw a line on the map along the base plate edge. Repeat the process with the second landmark and the intersection of the two lines is your exact location. See Figure 6. Another use for triangulation is in being able to return to an exact location. Say you are hiking and decide to stash a water bottle part way along the trail so you can drink it on your return trip and avoid carrying it for the whole hike. You take a look around, and stash the water bottle behind a rock. Next you pick out two permanent landmarks which are preferably about 90 degrees apart, and take a bearing on each. Make a note of each landmark and it’s bearing, then when you return to the general area all you need to do is position yourself where the two bearings match and you will find you hidden water bottle.

- Navigation Tips and Tricks

Understanding Maps : To be truly strong at orienteering and navigation, one must become very familiar with maps, and the abundance of information they contain. Unfortunately, it would require a separate article to fairly explain maps, but it’s still worth looking at some map basics here. Know the scale of your map. All maps list their scales in the margin. A scale of 1:250,000 means that 1 unit (be it inches, feet, meters, or whatever) on the map is the equivalent of 250,000 units in the real world. Most USGS maps are 1:24,000, (also known as 7.5 minute maps) where 1 inch equals 2,000 feet (3/8 mile) in other words 2.64 inches equals one mile, thus a 7.5 minute USGS map has a north-south extent of about 9 miles. Clearly, the smaller the scale, the more detail is revealed. Maps are drawn based on latitude and longitude lines. Latitude lines run east and west (that is, parallel to the equator) and measure the distance in degrees north or south from the equator (0° latitude), and are often called parallels. Longitude lines run north and south intersecting at the north and south poles. Longitude lines measure the distance in degrees east or west from the prime meridian that runs through Greenwich, England, and are often called meridians. Latitude and longitude are measured in degrees, minutes and seconds. One degree equals sixty minutes, and one minute equals sixty seconds. The latitude and longitude grid allows us to calculate an exact point using these lines as X axis and Y axis coordinates. Another way to identify a point on a map is with the Universal Transverse Mercator (UTM) coordinate system, which similar to latitude and longitude also uses a north/south and east/west grid. On the USGS maps you will see markings for both grids. The UTM grid is more precise than latitude/longitude because USGS maps identify UTM scales every thousand meters compared to only every 2.5 minutes (about 3500 to 5000 meters) for latitude and longitude. Working with one meter number, can be less confusing than working with three degrees, minutes, and seconds values. Trip Planning and Pseudo Maps : Before setting out on a back country trip into unfamiliar territory, it is wise to carefully study a map of the area, and make some notes. Note such things as landmarks, bearings between landmarks, distances and elevations. Notes of this type can save valuable time in the field, and will help you both stay orientated as well as assist in measuring your progress. I refer to such notes as a pseudo map. There is a tool on the Internet that I like to use to make my pseudo maps called ACME Mapper 2.0 . This tool allows you to enter a latitude/longitude and it returns a topographic map, which can be zoomed to various scales. It also allows you to mark spots on the map, and then it gives you the distance between marks as well as bearings to them. I find it faster than measuring distances with a ruler on the map, and a very precise way to calculate map bearings. Even with a pseudo map at hand sometimes it can be useful to track distances as you are hiking. A trick to do so is to count your double steps. Typically one double step (that is just counting the steps of one of your feet, while ignoring the other) is about five feet. So, a thousand double steps is about one mile. Also, if you keep an eye on your watch, and time yourself over known distances, you soon get an idea of how long it takes you to cover distances over various terrains. Altimeter : An altimeter can be a useful companion to your topographic map and compass, assuming one knows how to calibrate it. As you hike the altimeter approximates your current altitude (based on atmospheric pressure), and you can use that information as a "Z" coordinate, if you will, to determine your location on a map. Knowing your general location on the map, if you find the contour line of your current elevation you know your position. Aiming Off : When navigating to a target, if you realize that it could be easily missed if you get slightly off course one way, whereas missing the target the opposite way wouldn’t be a problem, you should use a trick known as aiming off. Consider this example; you leave your car at the north most end of a road that runs south to north. Leaving your car you walk SW at 240 degrees, making your literal return bearing 60 degrees. Returning you worry you will miss your car, if you get off course a bit and end up to far north, where there is no road. On the other hand, if you were to miss your car by being to the south you would cross the road, and you could just follow it back to the car. To avoid going to far north, you intentionally aim off so you will end up south of your car, thus guaranteeing you encounter the road. To do so, in this case, you might follow a return bearing of 70 degrees. Awareness : When hiking, or mountain climbing, in an area unfamiliar to you, make use of a topographic map and compass to learn the area. As you spot a landmark, such as a mountain peak, take a field bearing on it, and convert it to a map bearing. Starting at your current location pinpointed on the map (see the section on triangulation), plot the converted bearing on the map, and see which mountain it passes through, and then read the name of the unfamiliar mountain from the map. That quickly and that easily, you will learn the area, and that knowledge will help you stay oriented and lessens chances of becoming lost. Reverse Bearing : When hiking in and back out from somewhere one should know who to calculate a reverse (or opposite) bearing. For example, if you walked south following a 177 degree bearing, and turned around to return to your starting point what bearing would lead you back? Simply look at your compass and the straight line across the dial (the number on the opposite side) is the return bearing. The easiest way to calculate the opposite bearing is to add 180 degrees to the original bearing when it was less than or equal to 180 degrees, and to subtract 180 when the orginal bear was greater than 180. So for our example, the return bearing for the orginal bearing of 177 is 177 + 180 = 357 degrees (or almost due north). One can also leave his compass set to the orginal bearing and turn the compass 180 degrees by lining up the white end of the magnetic needle with the orienting arrow, as opposed to the normal red end of the magnetic needle. Another orientation trick, which I learned as a child from reading Louis L'Amour books, is to occasionally turn around and have a good look at the back trail, because a trail looks difference in the reverse direction. It’s also beneficial to pay attention to wind directions. For example some areas are known to have winds that blow from the west. If you are hiking in such an area, even if the wind isn’t blowing, you can often observe the results such as pine trees being leaner on their west side. We have all heard the saying that moss grows on the north side of trees. Why not verify if that is true in your area? If your trail crosses, or parallels a stream or river, pay attention to the direction it flows. Does it flow east, or northwest? Being aware, will reduce lost time, and disorientation, and make your outdoor experiences more rewarding. Wristwatch as Compass : A watch with an hour hand can be used as a makeshift compass. If is set to the correct time, simply point the hour hand at the sun, and in that position, the point halfway between the current hour and the 12, is south. In a vice versa way a compass can act as a watch. For example knowing the sun is in the east at 6:00 am, southeast at 9:00 am, south at noon, southwest at 3pm, and west at 6pm, you can take a bearing on the sun, and get a good idea of the current time.

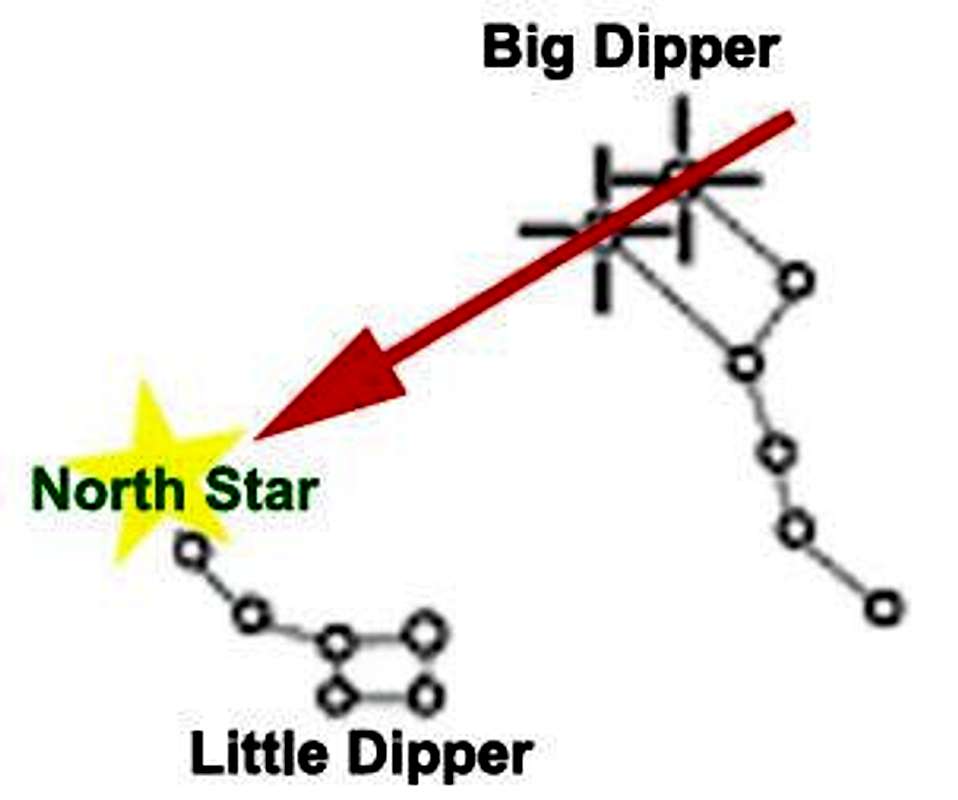

The North Star : In the Northern Hemisphere, Polaris (the North Star) is visible all year round. To find it, locate the Big Dipper and follow the two pointer stars at the end of the cup to the tail of the Little Dipper, Polaris is the last star on its tail, see Figure 7. Roughly the distance to the North Star from the Big Dipper is 5.5 times the distance between the two pointer stars forming the non-handle side of the cup. The Big Dipper rotates around Polaris. The North Star can be used to measure declination. At night, place two sticks in the ground lined up with the North Star, with the taller one to the north of the shorter. Set your compass dial at 360, and point the direction of travel arrow north at the longer stick. Look at the compass needle, and note the difference between its bearing and true north, the difference is declination. In the Northern Hemisphere, latitude is obtained by measuring the altitude of Polaris. At the Equator (0° of latitude) the North Star is on the horizon, making an angle or "altitude" of 0 degrees. Whereas at the North Pole (90° of latitude), Polaris is directly overhead making an angle or "altitude" of 90 degrees. Likewise, at 30°N the star is 30 degrees above the horizon, and so on. In other words, in the Northern Hemisphere, if you know your latitude, you can use that as an angle from the horizon to locate the North Star. To measure your latitude, point a stick at the North Star, then measure the angle the stick makes from a level horizon. Note, some compasses, include an inclination gauge (not covered in this article) by which you can easily measure the angle. Determine East and West Via a Shadow : To determine east and west, place a stick in the ground so you can see its shadow (alternatively, you can use the shadow of any fixed object). Ensure the shadow is cast on a level, brush-free spot. Mark the tip of the shadow with a pebble or scratch in the dirt; try to make the mark as small as possible so as to pinpoint the shadow's tip. Wait 10-15 minutes, as the shadow moves from west to east (the opposite side the sun moves on, ie the sun moves from the east to the west -- but both the shadow and the sun move in a clockwise direction). Mark the new position of the shadow's tip with another small object or scratch. Connect the two shadow tip markings with a straight line and you have an east-to-west line approximation. Midday readings give more accurate approximations. To get an exact east-to-west line join the marks from two shadows of equal length. In either the approximate or the exact case stand with the first mark on your left, and the second on your right, and you will be facing toward true north. Pay attention to your own shadow during the course of the day while on a long walk - if you are moving north your shadow will be over your left shoulder at sunrise and over your right shoulder at sunset. You might be the only object to throw a shadow when walking in barren terrain like a desert. Global Positioning System : The U.S. Department of Defense has 24 satellites orbiting the earth, which give off signals that handheld GPS devices can pick up and translate into a user’s position and altitude to within roughly 50 feet. These devices are useful, but are not a replacement for knowledge of the basics of orientation and navigation with a compass and map. Also always remember that a GPS unit is a delicate, battery powered device that can fail or be easily damaged. Never rely solely on, nor allow yourself to become dependent on such a piece of equipment. The tops of pine trees tend to dip to the north. If you do lose your way , keep a cool head - a cool head can accomplish much, a rattle one nothing. Note that lost people tend to wander in circles; as such above all don’t run around aimlessly. First stop, relax, and think, then look around for a familiar landmark, or climb a tree or a hill to try to find one. Estimate the time you have been traveling, and the remaining about of daylight - this will help you figure out how far you have traveled. If possible consult your compass, if not possible pay attention to sunset or sunrise which will indicate east and west, or use a wristwatch as a compass. Consider blazing your way by leaving small marks indicating the direction you have taken such as arrows in the dirt or snow, peeled bark on a tree, toilet paper on a tree branch, and/or rock cairns. If it gets dark it may be best to stay put, as such build a rousing fire, making it easier for others to find you and allowing you to stay warm. At night find the North Star and mark that direction on the ground to guide you come daylight.

- Other Outdoor Tips and Tricks

Estimating Remaining Daylight : If you can see the sun and the horizon you can estimate the remaining daylight time. To do so, hold your hand up so it appears that your pointer finger is just touch the bottom of the sun. Then count the number of finger widths to the horizon. Each finger is worth about 15 minutes of time. For example, if you can fit eight fingers (two hands without thumbs) between the bottom of the sun and the top of the horizon there is about two hours of daylight remaining. Note that this trick doesn't really work when one is near either of the poles, as the sun hovers over the horizon longer at those locations. If thirsty and can’t find water, suck on a pebble or a button, it will relieve the dryness. Make a sundial from a piece of stick stuck in the ground where the sun’s rays can cast a shadow from the stick onto the ground. Refer to a watch to mark the hours, then when the watch goes missing or the owners leaves camp, or the batteries die, you can use the sundial to tell time. To prevent sickness, keep your feet and inner cloths dry, your bowels open, and your head cool. A warm head makes you sweat causing you to remove your hat, and then leaving you open to a cold.

The surest way to stay both fit and healthy is to simple make a point of walking each and every day. Consider this statement by Soren Kierkegaard a 19th-century Danish philosopher, "Above all, do not lose your desire to walk. Every day I walk myself into a state of well-being and walk away from every illness." To dry the inside of wet boots, heat peddles in a frying pan or kettle, or in the fire and place them in the boots, shaking the boots now and then. Reliable Weather Indicators "Red at night, campers delight; red in morning campers warning." A red sunset indicates clear weather, whereas a red sunrise indicates rain and wind. Pale Yellow sky at sunset indicates wet weather. "Rain before seven quits before eleven." In other words morning rain often makes clear afternoons. Slow rain tends to last, but sudden rain is typically short in duration. Heavy dew indicates dry weather to follow. Daytime temperatures drop about five degrees Fahrenheit per 1,000 feet of elevation gain.

Seasons

In the Northern Sky the Big Dipper is one of the most familiar asterisms of the constellation Ursa Major (the Great Bear). As the Earth moves around the sun the angle of our view of the Big Dipper changes and thus is different for each season.

In summary, a compass is an invaluable tool that every outdoors enthusiast should understand how to use. Two of its main uses are to measure bearings, and to pinpoint locations. When working with bearings one needs to be aware of declination and how that causes map bearings and magnetic (field) bearings to differ. Remember it’s simply a matter of subtracting an east declination from a map bearing to convert it to a magnetic (field) bearing, and a matter of adding a west declination. Of course, when converting a magnetic bearing to a map bearing apply the opposite of the rule. Remember, the magnetic needle of a compass is for use in the field, and is never used on a map. Also recall that the top of a map is always north, so when taking map bearings always turn the compass housing to point the orienting arrow at the top of the map. Of course a compass isn’t the only thing that will help you stay oriented in the back country. Always study a map before entering unfamiliar territory. In the field always carry a map and pay attention to the surroundings, as well as make use of natural direction indicators, like shadows, stars, wind, and landmarks.

- About the Author

I considered myself to be an outdoors enthusiast. Very few activities provide me with as much joy as hiking, camping, skiing, mountain biking, rock climbing, ice climbing and exploring.

This passion began in my childhood. At the young age of 10 years, I climbed Chief Mountain in Glacier Park, MT, and not long after I back-packed the 26 mile from the USA/Canada border over Stoney Indian Pass to Goat Haunt.

Over the years, I have crossed paths with cougars, been charged by moose, and spooked by grizzly bears. I have stood on the Great Wall of China, strolled beaches in Australia, enjoyed winters in Canada, and lived in Asia. I have cycled the Golden Triangle from Banff, Alberta and the full C&O Canal Trail from Washington, DC. I have rock climbed at Stone Hill Montana, ice climbed in Ouray Colorado, scaled Denali in Alaska, explored the Copper Canyons of Mexico, skied the Trinity Chutes of Mt. Shasta California, and white-water rafted on the Gauley River of West Virginia. I have climbed to the highest point of all 50 states.

I don't like GPS and never use any type of electronic navigator.

- Enjoyed this Article?

If you enjoyed this article, perhaps you would like to read another article by this same author? Read, The Effort Scale of Highpointing the Fifty US States . I have published a book about my journey to the highest point of every U.S. state. The book, All Fifty: My Journey to the Highest Point of Every U.S. State , is available on Amazon.com.

View Compass Basics: An Introduction to Orientation and Navigation Image Gallery - 15 Images

Alpinist - Nov 19, 2007 3:56 pm - Voted 10/10

Nice addition to SP. Thanks for posting it.

vanman798 - Nov 19, 2007 4:14 pm - Hasn't voted

Your welcome! I enjoyed brushing up on my compass skills in order to write it.

Dmitry Pruss - Nov 19, 2007 4:22 pm - Voted 10/10

Nowadays most watches are dial-less, and therefore the rule should be made from analog into digital. The Sun is at 15 degrees true * military time (or one hour less if daylight savings time is in effect). A bit more complex formulas apply to sun shadow (add 180 deg), and to the Moon (subtact 13 degrees times number of days since New Mooon). Yeah, and as to retracing your steps ... most of the time I can 100% trust my dog. It is a fun and useful means of navigation :)

vanman798 - Nov 19, 2007 4:39 pm - Hasn't voted

Thanks for the digital rule. If you flesh it out a bit more I will gladly use it in the article. The Wristwatch compass rule is useful to know whether one uses an analog or a digital watch. From this rule one understands how to approximate directions based on the time of the day. If I know the time of day, but I don't have a watch, I can always scratch a drawing of one into the dirt and approximate directions based on the rule.

Mark Doiron - Nov 21, 2007 3:04 pm - Voted 10/10

Great article--thanks for this! FYI, you can use a compass with an inclination gauge to determine your latitude. Point a stick at the North Star, then measure the angle of that stick with a level horizon (a compass with an inclination gauge makes this easy). One may not think this is especially useful, but the inverse can be: The North Star is always located at an angle from your horizon approximately equal (within one degree) to your latitude. Don't bother looking anywhere else for it, and if you think you've found it, but it isn't at that angle, you haven't found it! --mark d.

vanman798 - Nov 22, 2007 12:08 pm - Hasn't voted

Great tip! I have included it in the article. Thanks a lot.

Corax - Nov 21, 2007 4:41 pm - Voted 10/10

Great addition.

tommi - Nov 22, 2007 6:19 am - Voted 10/10

A very good idea to post that article about something important like this, you did a good job.

zenalpinist - Nov 22, 2007 10:26 am - Hasn't voted

Great article! We need more people to work on their compass skills rather than their GPS skills. One way I help people remember to deal with declination in areas to the west of the line (or with East Declination) is the following: Field to Map: add the declination (and the way to remember is you are going forwards in the alphabet from F to M) Map to Field: subtract (and the way to remember is you are going backwards in the alphabet from M to F) Of course it would have to be reversed for those on the east half of the line. Good tips for aiming off too, blindly following the compass or GPS is not always the best way to go.

donhaller3 - Nov 22, 2007 12:18 pm - Voted 10/10

1) Two other tricks for remembering how declination works help in most of North America. "East is least and West is best." Visualizing the general shape of North America and remembering where the big hole at the top is(Hudson's Bay)--Shezam! roughly where mag North is-- helps this idiot. 2)If the map legend lists a "third north", grid north, the degree or so correction can be added or subtracted from from your declination correction. Not to worry if it's not there, but eliminating cumulative systemic error if it's there. It would be seen as a little set of arrows showing true, magnetic and grid north. Makes setting off the compass very easy by the way. 3)Finally, one may run across a bearing listed like "N67W." This is an alternate convention that is useful where you're doing engineering, surveying or air and sea navigation because it makes trig easier. Unless your curious, ignore it. http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Bearing_%28navigation%29 4)Anything somebody else says is an azimuth is a bearing in our author's sense.

singularity - Nov 26, 2007 3:32 pm - Voted 10/10

thx for adding it!

MakeItHappen - Nov 26, 2007 7:47 pm - Hasn't voted

Yet another reason why SP is such a useful and helpful website.

Moni - Nov 28, 2007 1:28 pm - Voted 10/10

Nicely done. I take issue with two terms, however. A bearing is a direction gotten from a compass with the quadrant scale (like N37W) while a direction from a compass with 0 - 360 is an azimuth. The term triangulation is incorrect: this technique is called resectioning and involves the intersection of any two linear features, which can be 2 compass directions but also a road and an elevation, etc. See here

vanman798 - Nov 28, 2007 3:03 pm - Hasn't voted

Synonyms. :) It seems there was a time when "bearing" was restricted to referring to the direction of a terrestrial object or point. And back then an "azimuth" referred to the direction of a celestial body. That distinction seems to no longer apply. I'm not sure, but prehaps the military uses the word azimuth instead of bearing.

Moni - Nov 28, 2007 8:10 pm - Voted 10/10

It is not an opinion. Look here - one of many sites which use the terms correctly. In fact, when you use 2 compass directions, it is called determining position by intersection, but it comes under resection Resection Azimuth

dpk - Nov 30, 2007 11:01 pm - Voted 10/10

great detail and links - an excellent reference tool thank you

idahomtnhigh - Nov 30, 2007 11:38 pm - Voted 10/10

I teach a land navigation class and I think or article was well done, Thanks for the post.

vanman798 - Dec 13, 2007 12:16 pm - Hasn't voted

That is a great compliment coming from a land navigation teacher. Thank you very much.

cp0915 - Dec 7, 2007 1:18 pm - Voted 10/10

You did a terrific job on this page! Excellent, truly.

chel3178 - May 31, 2008 10:39 pm - Voted 10/10

This looks really great. I bought a compass but haven't really used it yet, though I haven't needed it yet either. But, at some point I will and I'd like to practice where I can't get lost. I'm wondering how I can save articles also without commenting for future reference...

You need to login in order to vote!

Don't have an account.

- Rating available

- Suggested routes for you

- People who climb the same things as you

- Comments Available

- Create Albums

- PRO Courses Guides New Tech Help Pro Expert Videos About wikiHow Pro Upgrade Sign In

- EDIT Edit this Article

- EXPLORE Tech Help Pro About Us Random Article Quizzes Request a New Article Community Dashboard This Or That Game Popular Categories Arts and Entertainment Artwork Books Movies Computers and Electronics Computers Phone Skills Technology Hacks Health Men's Health Mental Health Women's Health Relationships Dating Love Relationship Issues Hobbies and Crafts Crafts Drawing Games Education & Communication Communication Skills Personal Development Studying Personal Care and Style Fashion Hair Care Personal Hygiene Youth Personal Care School Stuff Dating All Categories Arts and Entertainment Finance and Business Home and Garden Relationship Quizzes Cars & Other Vehicles Food and Entertaining Personal Care and Style Sports and Fitness Computers and Electronics Health Pets and Animals Travel Education & Communication Hobbies and Crafts Philosophy and Religion Work World Family Life Holidays and Traditions Relationships Youth

- Browse Articles

- Learn Something New

- Quizzes Hot

- This Or That Game

- Train Your Brain

- Explore More

- Support wikiHow

- About wikiHow

- Log in / Sign up

- Navigation and Directions

How to Use a Compass

Last Updated: March 29, 2024 References

Learning the Basics

Using the compass, finding your bearings when lost.

This article was co-authored by Josh Goldbach . Josh Goldbach is an Outdoor Education Expert and the Executive Director of Bold Earth Adventures. Bold Earth leads adventure travel camps for teenagers all over the world. With almost 15 years of experience, Josh specializes in outdoor adventure trips for teens both in the United States and internationally. Josh earned his B.A. in Psychology from Eckerd College in St. Petersburg, Florida. He’s also trained as a wilderness first responder, a Leave No Trace master educator, and a Level 5 Swiftwater rescue technician. There are 9 references cited in this article, which can be found at the bottom of the page. This article has been viewed 1,586,839 times.

A compass is an essential tool in wilderness survival. Along with a good quality topographical map of the area you're navigating, knowing how to use a compass will ensure that you're never lost. You can learn to identify the basic components of the compass, take an accurate reading of your bearings, and start developing the necessary skills of navigation with a few simple steps. See Step 1 to start learning to use your compass.

How do you use a compass?

Hold the compass so it's flat on your palm with your palm centered in front of your chest. Use the magnetic needle for guidance—it will spin unless you're headed north. Adjust the direction-of-travel arrow on your compass so it's pointing in the direction that you're traveling.

- The baseplate is the clear, plastic plate on which the compass is embedded.

- The direction of travel arrow is the arrow in the baseplate pointing away from the compass.

- The compass housing is the clear, plastic circle that houses the magnetized compass needle.

- The degree dial is the twistable dial surrounding the compass housing that displays all 360 degrees of the circle.

- The magnetic needle is the needle spinning within the compass housing.

- The orienting arrow is the non-magnetic arrow within the compass housing.

- The orienting lines are the lines within the compass housing that run parallel to the orienting arrow.

- Turn the degree dial until the orienting arrow lines up with the magnetic arrow, pointing them both North, and then find the general direction you're facing by looking at the direction of travel arrow. If the direction of travel arrow is now between the N and the E, say, you're facing Northeast.

- Find where the direction of travel arrow intersects with the degree dial . To take a more accurate reading, look closely at the degree markers on the compass. If it intersects at 23, you're facing 23 degrees Northeast.

- True North or Map North refers to the point at which all longitudinal lines meet on the map, at the North Pole. All maps are laid out the same, with True North at the top of the map. Unfortunately, because of slight variations in the magnetic field, your compass won't point to True North, it'll point to Magnetic North.

- Magnetic North refers to the tilt of the magnetic field, about eleven degrees from the tilt of the Earth's axis, making the difference between True North and Magnetic North different by as many as 20 degrees in some places. Depending where you are on the surface of the Earth, you'll have to account for the Magnetic shift to get an accurate reading.

- While the difference may seem incidental, traveling just one degree off for the distance of a mile will have you about 100 feet (30.5 m) off track. Think of how off you'll be after ten or twenty miles. It's important to compensate by taking the declination into account.

- In the US, the line of zero declination runs up through Alabama, Illinois, and Wisconsin, [5] X Research source at a slight diagonal. East of that line, declination orients toward the West, meaning that Magnetic North is several degrees West of True North. West of that line, the opposite is true. Find out the declination in the area in which you'll be traveling so you can compensate for it.

- Say you take a bearing on your compass in an area with West declination. You'll add the number of degrees necessary to get the correct corresponding bearing on your map. In an area with East declination, you'll subtract.

- Twist the degree dial until the orienting arrow lines up with the north end of the magnetic needle. Once they're aligned, this will tell you where your direction of travel arrow is pointing. [6] X Research source

- Take off local magnetic variation by twisting the degree dial the correct number of degrees to the left or right, depending on the declination. See where the direction of travel arrow lines up with the degree dial.

- If visibility is limited and you cannot see any distant objects, use another member of your walking party (if applicable). Stand still, then ask them to walk away from you in the direction indicated by the direction of travel arrow. Call out to them to correct their direction as they walk. When they approach the edge of visibility, ask them to wait until you catch up. Repeat as necessary.

- Draw a line along the compass edge and through your current position. If you maintain this bearing, your path from your current position will be along the line you just drew on your map.

- Rotate the degree dial until the orienting arrow points to true north on the map. This will also align the compass’s orienting lines with the map’s north-south lines. Once the degree dial is in place, put the map away.

- In this case, you'll correct for declination by adding the appropriate number of degrees in areas with West declination, and subtracting in areas with East declination. This is the opposite of what you'll do when first taking your bearing from the compass, making this an important distinction.

- Repeat this process for the other two landmarks. When you’re done, you will have three lines that form a triangle on your map. Your position is inside this triangle, the size of which depends on the accuracy of your bearings. More accurate bearings reduce the size of the triangle and, with lots of practice, you may get the lines to intersect at one point.

Community Q&A

- You can also hold the compass square to your body by holding the sides of the baseplate between both hands (making L shapes with your thumbs) and keeping your elbows against your sides. Stand facing your objective, look straight ahead, and square yourself with the object by which you are taking your bearing. The imaginary line extending out from your body will travel through your compass along the direction of travel arrow. You can even rest your thumbs (against which the end of the compass is resting) against your stomach to steady your hold. Just be sure you aren't wearing a big steel belt buckle or some other magnetic material close to the compass when doing this. [12] X Research source Thanks Helpful 0 Not Helpful 0

- Trust your compass: 99.9% of the time it is giving you the correct direction. Many landscapes look similar, so again, TRUST YOUR COMPASS. Thanks Helpful 7 Not Helpful 0

- For maximum accuracy, hold the compass up to your eye and look down the direction of travel arrow to find landmarks, guide points, etc. Thanks Helpful 6 Not Helpful 3

You Might Also Like

- ↑ https://americanhiking.org/resources/how-to-use-a-compass/

- ↑ https://www.seattleymca.org/blog/how-use-compass

- ↑ https://irp.fas.org/doddir/army/fm3-25-26.pdf

- ↑ https://www.sco.wisc.edu/learning-center/magnetic-declination/

- ↑ https://www.nationaltrust.org.uk/features/how-to-read-a-compass

- ↑ https://www.nwcg.gov/sites/default/files/publications/pms475.pdf

- ↑ https://www.usgs.gov/educational-resources/method-1

- ↑ https://www.princeton.edu/~oa/manual/mapcompass3.shtml

- ↑ http://www.princeton.edu/~oa/manual/mapcompass3.shtml#Scenarios

About This Article

To use a compass, hold the compass flat on your outspread hand in front of your chest. Next, turn the degree dial so that the orienting arrow lines up with the magnetic arrow inside the compass. Then, look at the travel arrow on the baseplate of the compass to tell you which direction you’re facing. For example, if you want to find which direction is North, rotate slowly with the compass until the travel arrow is pointing to the N on the dial. If you want to learn how to use a compass to find your bearings on a map, keep reading the article! Did this summary help you? Yes No

- Send fan mail to authors

Reader Success Stories

Mario Manzur

Jun 23, 2020

Did this article help you?

Gabriel McLaughlin

Jun 8, 2021

John Connolly

Mar 30, 2018

Ed Sommerfeld

Jan 21, 2019

Keith Brooks

Aug 18, 2017

Featured Articles

Trending Articles

Watch Articles

- Terms of Use

- Privacy Policy

- Do Not Sell or Share My Info

- Not Selling Info

wikiHow Tech Help Pro:

Level up your tech skills and stay ahead of the curve

So how do we resolve the issue of these two different Norths? Declination! Declination is simply the difference in degrees between true north and magnetic north for any particular area. But be aware: the amount of difference between true and magnetic north varies by location. (Hang in there – this gets really cool!)

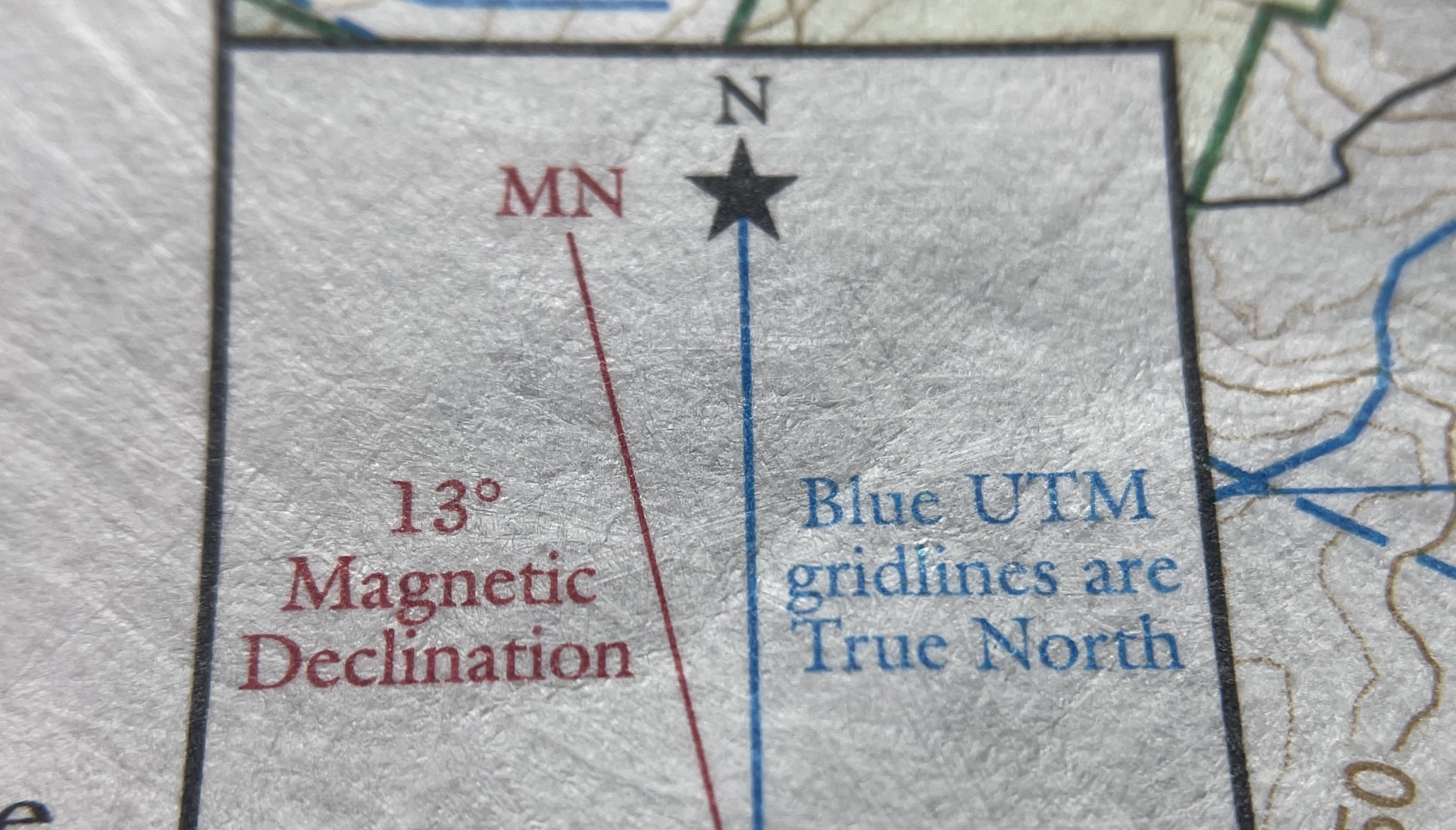

Now if you’re using a topographic map, it probably has a legend that displays the declination as two straight lines, where true north has a star at the top of the line and magnetic north is indicated as MN on the other line. If your map isn’t fairly new, please feel free to ignore this legend, because not only does declination vary by area – it varies over time. Just because the declination was 12 degrees west when the map was published, it doesn’t mean that it still is.

So what’s a person to do? Just type in the zip code or coordinates for the area you’ll be hiking at this NOAA website and you’ll have the exact current declination figured out for you!

Once you know the declination – it will be expressed in degrees west (a negative number) or degrees east (a positive number) – you should be able to adjust your compass appropriately. Sometimes there is a screw to adjust this, but it varies by model. If you no longer have the owner’s manual, you might be able to find directions at the compass manufacturer’s website.

For more information about magnetic declination and how to use your compass, we encourage you to view this page on the National Wildfire Coordinating Group website .

Traveling by Compass

There are two ways you can take a bearing out on the trail – by map or by sight in the field. Here is a very brief explanation of each method.

By map: place your map and compass on the ground. Then mark your current position as well as your intended destination and draw a straight line between them. Line up the edge of your compass on this line so that the travel arrow is in the direction you wish to travel, then twist the azimuth ring (which is simply the ring with the measured units of degrees on a compass) until north on the map and the orienting arrow are aligned. When you remove your compass from the map and turn until the orienting arrow and red magnetic needle are lined up, you will be in the right direction.

By sight, it’s much simpler. If you are heading to a mountain for example, point at it from your current position with the travel arrow on the compass. Then rotate your azimuth ring until the orienting arrow is lined up with the red end of the magnetic needle pointing towards north. Continue on your path so that the needle and its housing remain intact and you should have no problem reaching your destination.

- Odnoklassniki icon Odnoklassniki

- Facebook Messenger

- LiveJournal

How to Use a Compass

Similar Entries In: Technique , Gear , Hike Safety , Recommended Reads , Bushwhack , True Bushwhack , Tutorials , Winter Gear .

Initial bearing

Disclosure: This content may contain affiliate links. Read my disclosure policy .

If you’ve found learning how to use a compass intimidating, this guide simplifies the journey and makes each step along the way a confident and enjoyable one.

The first time I navigated by compass was on January 17, 2021 . It was so easy, I couldn’t believe it! On a solo winter bushwhack, I set a bearing beside Biscuit Brook in the Catskills, stepped off the trail, and headed directly up Fir Mountain . I didn’t have to tweak my compass until I got to the summit. Huge success! First time out of the gate! If I can do it, you can do it too.

Like most people, I’d always been too intimidated to learn how to use a map and compass to navigate. Turns out it’s actually super easy; the problem is usually how it’s taught.

This post takes a non-jargon-based approach that will walk you through the whole process, step-by-step.

Table of Contents

Basic Map & Compass Skills Make You Feel Amazing

The sense of freedom, self-reliance, and the thrill of exploring uncharted territory become more than just skills; they become the gateway to unforgettable adventures and the joys of self-discovery.

Knowing your map and compass navigation basics means…

- You’ll never feel lost again — in fact, you’ll become instantly un-get-lost-able ;

- You’ll be able to hike in a straight line through even the densest fogs and forests;

- You’ll feel a much deeper connection to the terrain around you;

- You won’t have to rely on a smartphone for backcountry navigation;

- You’ll feel 100 times more self-reliant. You will not believe the wonderful sense of freedom and accomplishment that comes from navigating with map and compass.

Learning How to Use a Compass is EASY!

You can learn how to use a compass in minutes. You will learn it in minutes. There are only 4 simple steps…

- Orient your map and compass;

- Set a bearing;

- Hang the compass around your neck;

- There’s no fourth step!

LOL. Let’s walk through it, step by step. Afterwards, we’ll get into the gear, the jargon, and the nuances. For now, I just want to show you how easy it is…

Note: This guide is focussed solely on how to set a bearing and navigate with a compass. It does not teach important map reading skills — i.e. interpreting map symbols, contours, etc. — which are, comparatively, much easier to learn.

How to Use a Compass for Hiking

Mastering the art of map and compass navigation opens up a world of possibilities for hikers and outdoor enthusiasts. It’s not just a skill; it’s a key that unlocks the beauty and wonder of the great outdoors. How do you use a compass step by step? Here’s exactly how…

STEP 1: ORIENT YOUR MAP & COMPASS

Your first step is to make sure that your map , your compass and your body are all facing magnetic north .

Turn your compass dial until it shows N at the index mark 1 under the direction-of-travel arrow 2 .

Line up a side edge of your compass with the map’s vertical gridlines 3 .

Next, holding the map and compass, turn your body until the red arrow is inside the red “shed” 4 .

Now that “red is in the shed”, you, your map, and your compass are all facing magnetic north .

Why skim the surface when you can plunge into the heart of every trail? By joining Mountain-Hiking.com on Patreon, you’re not just gaining access; you’re stepping into a passionate hiker’s world, complete with vivid imagery and personal insights. Get full access to all content on this website instantly and enjoy unique supporter benefits.

STEP 2: TAKE A BEARING

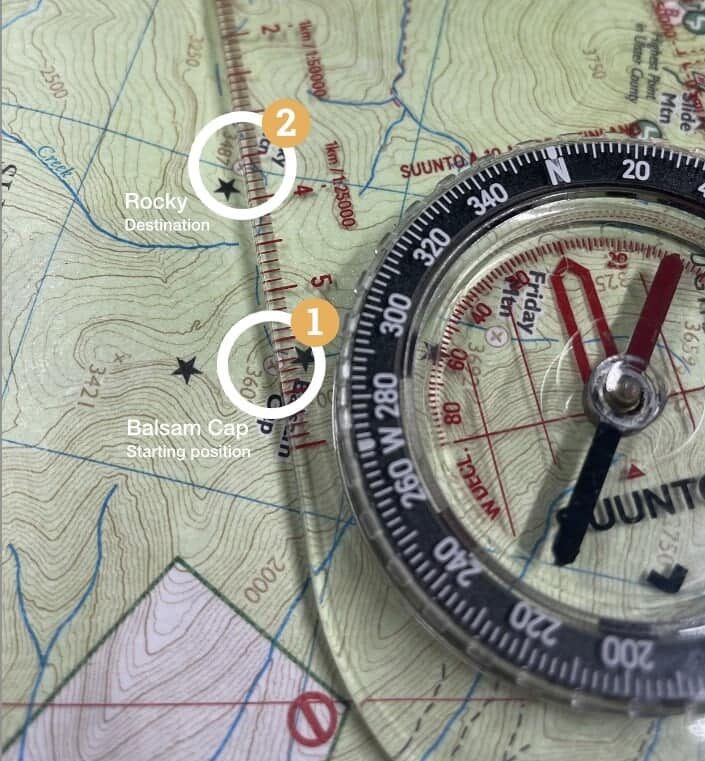

In this example, we’ll set a bearing between the summits of Balsam Cap and Rocky mountains in the Catskills.

Simply place the edge of your compass’ baseplate so it forms a line between your current/starting position 1 and your intended destination 2 .

While keeping the compass tight against the map — so it doesn’t shift — turn your compass dial until the red orientation lines on the dial are facing north and are once again parallel with the vertical gridlines on your map.

In this example, your initial bearing, visible at the index tick , would be 247°.

Adjust your bearing…

If true north and magnetic north were one and the same, you would now be finished and ready to set off.

Usually, they are not, and because they are not we have to make a small adjustment to account for the difference between the two.

This is the part that confuses people the most. But it’s easy…

Every topographic map includes the key you need. Near the edge of your map, look for a small diagram like the one below which will tell you that (in our example area) Magnetic North is 13° west/left of True North.

Elsewhere in the world, this value is very different. This is why you need high-quality topographic maps for any area you plan to navigate with a map and compass. (Thanks to NYNJTC for allowing me to use their amazing maps for this tutorial.)

Okay. 13° West. How do we use this piece of information? Read on…

It’s easy to remember…

If Magnetic North is to the LEFT of True North, turn your dial to the LEFT (counter-clockwise). If Magnetic North is to the RIGHT of True North, turn your dial to the RIGHT (clockwise). The mnemonic for this is: “West is best / East is least.”

In our example, magnetic north is to the west/left of true north, so we will turn our dial 13° to the left. This adds to our initial bearing: 247 + 13 = 260°.

For now, you no longer need your map — and the bearing itself is no longer very important either because…

Your compass is ready to use!

STEP 3: USING YOUR COMPASS

First, hang the compass around your neck. Good job. 50% done.

Second, whenever you want to check which way to walk, hold the compass in your hand and turn your body until red is back in the shed 1 . Then simply follow the direction of travel arrow 2 .

That’s it! 100% done!

You just learned how to use a compass. Remember, practice makes perfect. The more you practice navigating with a map and compass, the more confident you’ll become in your navigation skills.

Get the Step-by-Step Visual Guide

If you’d like an even more thorough walk-through of the whole process — with clearly labeled photos of every single step — grab this step-by-step visual guide from my Ko-fi store…

- Map & Compass Navigation: A Step-by-Step Visual Guide

“As a very active senior citizen Catskill mountain hiker I would highly recommend your map and compass navigation skills guide. It refreshed my memory of a long forgotten skill in 10 minutes. It’s the best 12 bucks I’ve spent in a long time.” — Bob G .

You’ll also learn…

- The best compass to buy

- How to deal with magnetic interference

- How to think about terrain issues

- How to navigate in low visibility (e.g. thick fog and dense forest)

- The individual part names of your compass

The step-by-step visual guide is designed in 9:16 aspect ratio as a PDF, perfect for reading on your phone. This is independently produced content with excellent reviews. Buy it here . I appreciate your support.

Frequently Asked Questions

How do you read a compass for beginners.

There are only three steps. This guide shows you how to read a compass correctly. The Step-by-Step Visual Guide breaks it down even further, with more detail and clear photographs of each step.

How to use a compass for orienteering?

The process is the exact same as shown above. A compass is used in combination with a topographic map to orient yourself and direct your travel.

How do you find north on a compass?

The red needle always points north. Just make sure to hold it away from any other metal.

Does a compass always point north?

In the absence of any magnetic interference, the red needle on every compass always points north.

Which arrow do you follow on a compass?

When used correctly, the red arrow always points north.

You might also enjoy…

- Challenge › Fire Tower Challenge 2024

- New › Say Goodbye to Blisters

- Follow › Sean’s content on Instagram

- Identify › Black Fly Season Means Black Fly Bites

- Explore › The Hardest Hikes You Can Do

- Hike More › Catskills , Adirondacks , Hudson Highlands , Gunks , Berkshires

Get full access…

Get instant access to the full version of this site and enjoy great supporter benefits: full galleries, full trail notes, early access to the latest content, and more.

Hot on the website right now…

Follow for more….

Follow my @TotalCatskills content on Instagram for regular hiking inspo and safe, inclusive community.

I also stay active on Facebook and Threads .

You might like…

One response to “ how to use a compass ”.

- Pingback: How to Properly Use a Compass: A Clear and Confident Guide - surviving another day

Your comments are welcome here… Cancel reply

Hello, I’m Sean

I write independent hiking content to help hikers like you find amazing hikes in the Catskills, Adirondacks, Gunks, Hudson Highlands, Taconics and beyond.

On social media, I’m @TotalCatskills. Follow me on Facebook , Twitter , YouTube and Instagram .

My free weekly hiking newsletter is low key awesome.

You won’t regret signing up…

How To Use A Compass | The Complete Beginners Guide

It’s hard to imagine life without the handiest orientation tool of them all, the humble compass. If you are a true hiker, camper, hunter or even just general outdoors enthusiast then you would definitely have a basic understanding of how to use a compass. You would swear by one of these bad boys as you would never know when you could become lost or stranded for whatever reason.

The humble compass has been used and improved over the years and has surprisingly been around for centuries! In fact, it is well documented that the first compass can be dated back to the ancient Han dynasty of China between 202 BC – 220 AD. They were created from a naturally magnetised ore of iron called ‘Iodstone’. As time progressed and improvements were made, they were then conveniently upgraded using iron needles. These iron needles were magnetised by striking them with a lodestone. That is where they get their form that we know of today. They were more than likely created as navigational backups for when the sun, stars, or other landmarks could not be seen. But enough of the history lesson as this article is designed for you who want to learn how to use a compass. Not only that, we’ll try to make it as simple as possible for you to do so!

Why would you need to learn how to use a compass?

Learning to use a compass is a basic outdoor skill that you should learn and master if you are serious about making sure that you never get yourself lost for whatever reason. The skill itself is pretty much like learning to ride a bike, once you do it a few times and succeed and you gain confidence within it, you’ll find that it’s very hard to forget. Sure, there’s a ton of gizmos and gadgets out there today that can do it all for you but in a way, they kind of dumb you down a bit. Not only that, what happens if you run out of battery or the power grid goes down? If it ain’t broke, don’t fix it. This rings true with the ancient skill of compass reading. So when all else fails, it’s just a heck of a lot more reassuring to be able to get out the old map and compass and just put your sure fire skills to the test!

Things you should understand before you begin

There are a few things to think about before even attempting to take your chances in the lost art of orienteering. Any expert would tell you that it’s super important to make sure that you get your head round these small issues before you begin. So let’s go through some of the basics first and then with extra confidence, take those skills out onto the field.

Getting to know your compass

If you have never even laid your eyes upon a compass before then you’ve come to the right place. Here we have some of the most common components of a compass, what they look like and their function.

Take note that a lot of compass designs may vary but they all share one common factor. That is that they include some sort of magnetized needle which orients itself to the magnetic fields of the earth. The most simple and common design is the baseplate compass, A.K.A. ‘The field compass’. We have chosen to base our learnings on this design due to it’s common nature. It features the following simple components which you should familiarize yourself with to enable you to continue forward.

Baseplate: The clear plastic, rectangular shaped plate which the compass housing is mounted on. It’s transparent to enable the user to hover it over a map and see the map underneath without any restrictions. It has a ruled edge to help with triangulation and contains directional lines/rulers and scaled numbers to help the user to navigate.

Scales & Rulers: The lines and numbers marked out along the edges of the baseplate. These numbers help the user to convert distances on a map to real life distances on a scaled level (Ratios). Eg: 1cm on the map equals 1km on the ground. Scales will vary from map to map. Depending on the maps scale, you may need to convert your compass scale to match that of your map before you begin. Meaning, if your compass is in inches and your map is in cms, you will have to convert your map to inches to suit your compass. The good thing is that when you do it once, you don’t have to keep doing it for the duration of the map usage.

Compass housing: The clear plastic, liquid filled, raised circular container part which houses the magnetic needle. It’s the main part of the compass in terms of function. The needle spins inside of the container as the user either rotates its body or the dial itself.

Direction of travel arrow: Marked on the baseplate, the arrow that begins at the compass housing and points away from it towards the top/front side of the compass. Shows the user which direction to point the compass to obtain a bearing in the direction that they wish to travel in. The user would hold the compass flat and the direction of travel arrow would face outwards, away from the user.

Magnifier: Small, circular magnifying glass used to help the user see smaller details on the map.

Index Pointer/Index Line: The base end of the direction of travel arrow. Begins at the edge of the dial and is where the user takes degree readings to navigate their path.

Degree dial: Rotating circular dial which surrounds the compass housing and displays all 360 degrees of the circle.

Declination Scale/Marks: This part is used to orient the compass in an area with known declination (When magnetic north and true north don’t align) Declination is a term used to show the difference between the 2 ‘norths’ There are many variables that can occur to change the state of declination. Knowing how to adjust your compass for it is vital.

Orienting Arrow: The non-magnetic arrow marked on the base/floor of the housing. Commonly marked in a colour such as red. It rotates with the housing when the dial is turned. When lined up with the magnetic needle, it ensures its user is properly following its bearing.

Orienting Lines: The lines inside the compass housing that run parallel to the orienting arrow. They rotate with the orienting arrow.

Needle: The needle is a magnetised piece of metal that spins within the compass housing. It’s the key component of a compass. One of the ends of the needle is commonly coloured red and and will always point to magnetic north (Not true north as they can be up to hundreds of miles apart depending on your location).

Understanding the difference between True North/Flat North or Magnetic North

Just because there are 2 Norths to think about, it doesn’t mean that it has to be confusing so let’s look at how to easily distinguish between the 2 to save you from any further headaches!

True North or Flat North: This is a fixed point on our earth realm. The two ends of the earth realms axis are documented as the geographic poles, North and South – known as True North and True South.

Magnetic North: On the other hand, magnetic north isn’t fixed and can vary depending on where you are located at the time. The term Magnetic North refers to the tilt of the magnetic field. Magnetic north is estimated to be about 11 degrees from the tilt of the earth’s axis. Meaning that the difference between true north and magnetic north can differentiate up to 20 degrees in some places. If you want the most accurate reading possible then it is important to account for the magnetic shift. Even the tiniest of miscalculations could throw you off kms from where you want to be.

Adjusting your compass for declination

First of all, what even is declination? Declination is the angle between true north and magnetic north. This angle can vary depending on the user’s location and it will gradually change over time due to the shifting of the earth’s tectonic plates.

Most maps will have declination diagrams as well as that date that it was last revised so you can use those figures to more accurately locate your starting position. Of course, the newer the map, the more accurate the figures will be as the declination will change over time. You would usually find an angle and a direction. For example, your map may show something like ‘11 degrees West’

Any time you venture out, it is advised that you check your maps to see what state they are in and how old they are. Some of the older maps may be a little tricky so you might want to check online for any updated maps of the area. You may even be able to find the declination somewhere on the internet which you can write down and use as a reference for your expedition.

Once you have obtained your declination figure, you should either add the figure from your compass bearing for west or subtract the figure to your compass bearing for east. An easy way to remember whether to add or subtract is “ West is best and East is least .” So for West declination, add to the true reading (West is best, and therefore a larger number) and for East declination subtract from the true reading (East is least, and therefore a smaller number).

How to hold your compass

One thing that you should always remember is to hold the compass flat. Whether that be on the palm of your hand or resting on a map. Keep the compass flat at all times.

You should also establish the direction that you are actually facing to get a feel of how the compass functions. You can do this by orienting yourself. Have a look at the magnetic needle, as you hold the compass flat in the palm of your hand and rotate your body. The needle should swing from side to side depending on which way you rotate.