- Transportation

The Cruise Industry Is On a Course For Climate Disaster

T o future archeologists, mega cruise ships might be some of the strangest artifacts of our civilization—these goliaths of mass-engineered delight, armed with dangling water slides and phalanxes of umbrellas. Looking up at one, you might gain the impression that cruise companies are trying to awe their customers into having a nice time. We have built battleships of pleasure, toiling the world’s oceans, hunting for fun.

It probably won’t come as a shock that the whole thing isn’t exactly sustainable. A medium-sized cruise ship spews greenhouse gas emissions equivalent to those of 12,000 cars , while environmentalists accuse big industry players of investing little in decarbonization, and of covering up endless delay tactics in a heavy coat of greenwash. And for years, the industry has been dogged by bad PR from everything from routine dumping of toxic sludge to increasingly organized outrage from communities tired of hordes of tourists getting dumped at their docks.

The big question, though, is whether those customers buying cruise packages to the Bahamas or Alaska particularly care. It’s easy to make the case that they don’t. Despite the industry’s continued investment in new fossil fuel-powered ships, cruise ticket sales are projected to climb back to record 2019 sales levels this year after a hit during the pandemic, according to the latest industry association report .

More from TIME

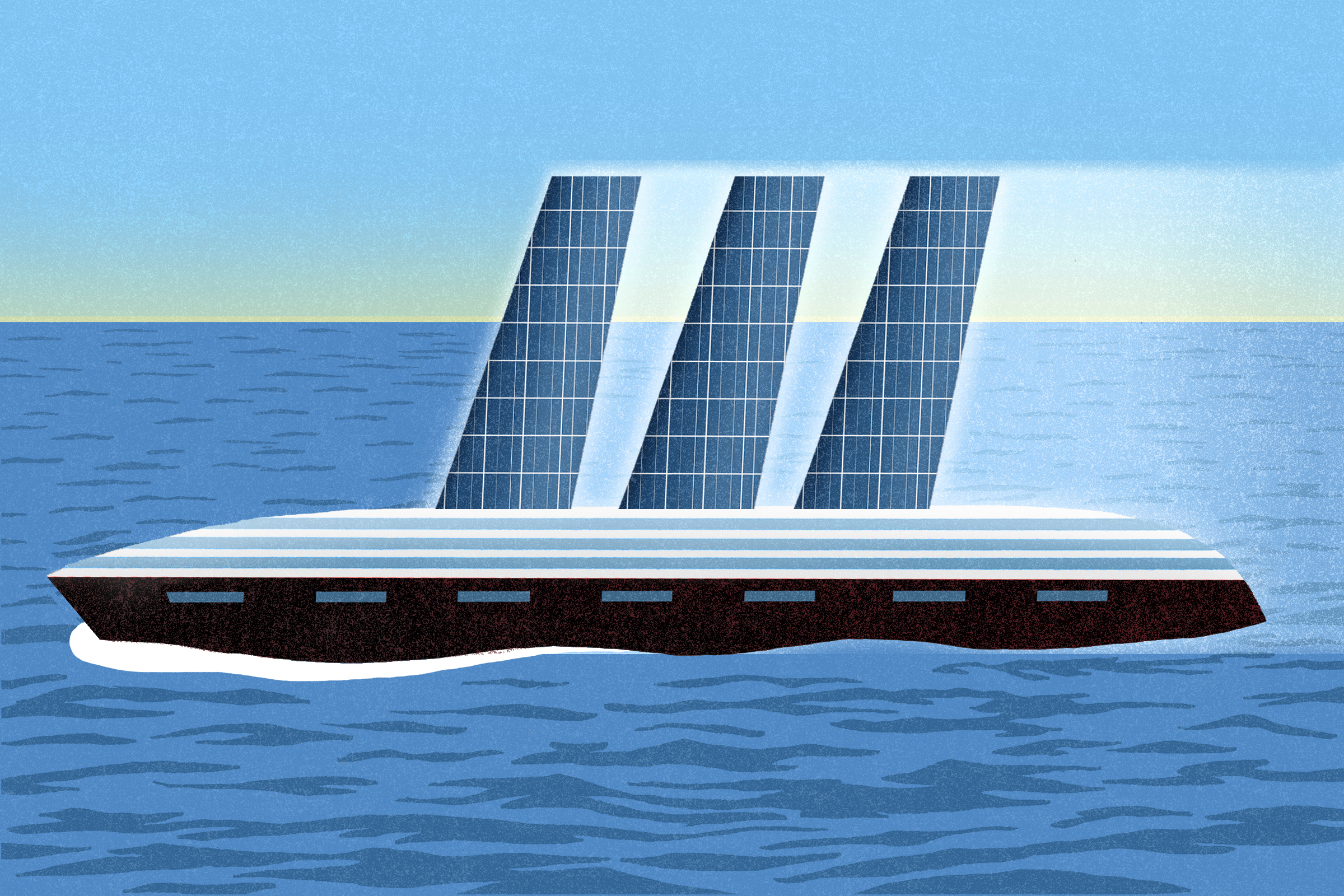

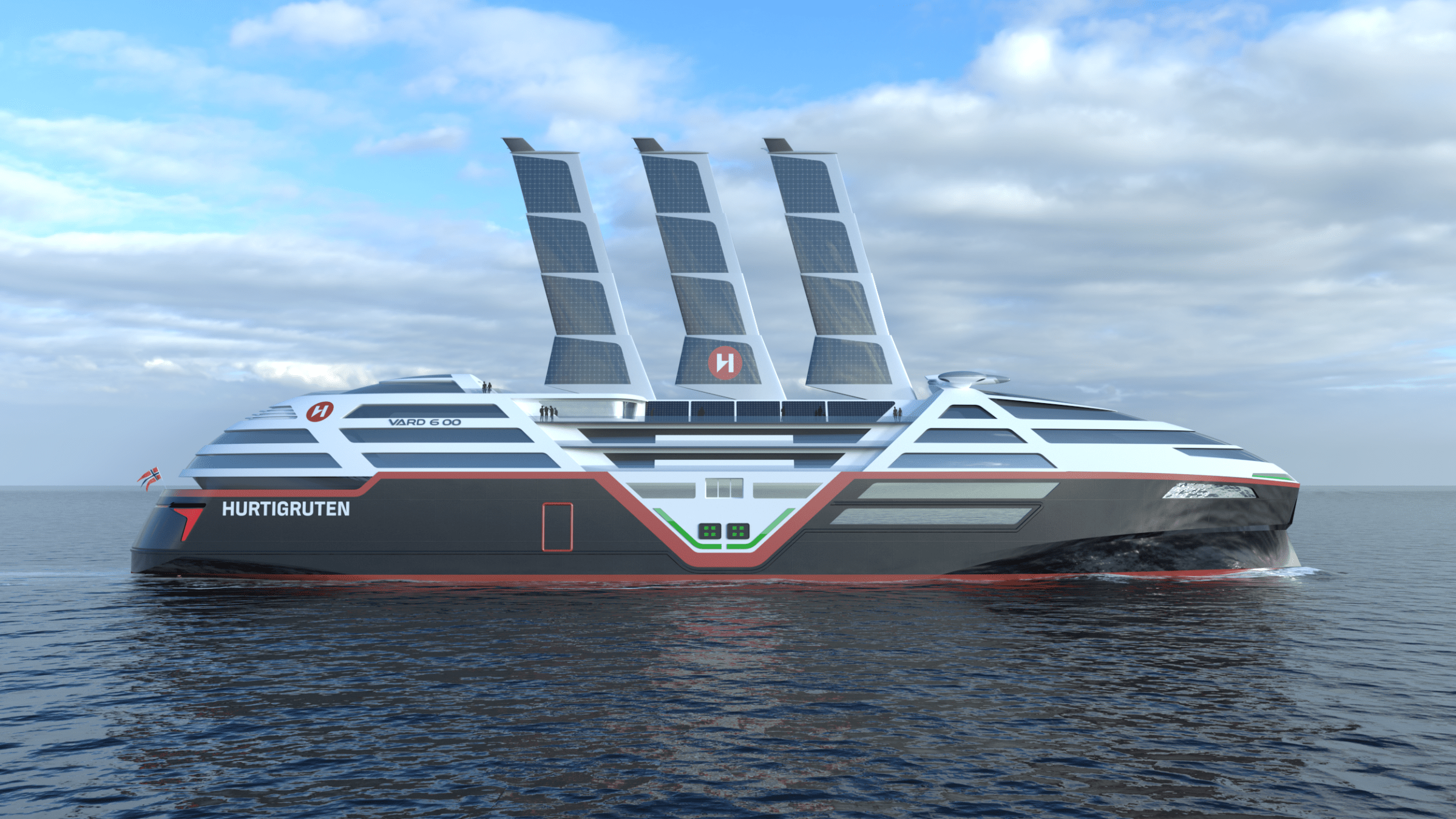

At least one cruise company, though, is betting that at least some potential customers care about sustainable vacations. Hurtigruten, a specialty cruise line based in Norway, says it has built its last fossil fuel-powered ship. On June 7, the company unveiled new details about the technologies it’s testing in pursuit of the world’s first zero-emission cruise ship, and renderings of what the boat might look like. Instead of towering over the ocean, the ship seems to cling close to the water, the better to reduce air resistance. In place of smokestacks, the designers envision retractable sails that double as solar panels. It runs on batteries instead of the thick, sticky fuel oil that powers most ships. And it’ll be ready, the company hopes, by 2030.

With time running short to phase out fossil fuels and avert the worst effects of climate change, the moral argument is compelling. But big businesses often make their decisions on what they might consider more practical concerns than what is “right” and “wrong.” It’s possible that Hurtigruten and its zero-emissions vessels could turn the industry ship around. But it could just be a green fluke, a new offering for a small slice of climate-conscious vacationers, as the rest of the industry chugs on as before.

Designing a green cruise line

Just about every CEO wants to be counted as an environmentalist these days. But Daniel Skjeldam, the CEO of Hurtigruten is one of those few who doesn’t dance around one of the more uncomfortable dimensions of our climate problem: the apparent conflict between the endless pursuit of more, bigger, better, and the limits of the earth’s biosphere.

“I think it’s sheer wrong to build bigger and bigger and bigger cruise ships,” Skjeldam says. The average cruise ship has around 3,000 passengers, but cruise companies have been investing in ever-bigger liners. “7,000 [passengers], 8,000, 9,000,” Skjeldam says. “It’s just wrong.”

The idea of running a cruise line occurred to Skjeldam back in 2012. Hurtigruten (the name means “Express Route” in English) was losing money, and Skjeldam, then commercial director at European budget airline Norwegian Air Shuttle, thought he could turn things around. He wasn’t in consideration for the role, though, so over the course of several weeks, the ambitious then-37-year-old executive repeatedly called through to the switchboard at the office of the company’s chairman, until finally he was able to come in and give his pitch in person.

It wasn’t long after that Skjeldam, officially appointed as CEO in October of that year, was on a Hurtigruten ship sailing past the Svalbard archipelago, home to the world’s northernmost inhabited town. He was on the bridge, having a cup of coffee with the captain, a five-decade veteran at the company, who pointed out a glacier several miles away. When he started sailing for the company in 1980, the captain said, the glacier had reached all the way to where they were floating now.

The experience, for Skjeldam, was eye-opening, and under his leadership, the company began making investments in sustainability long before some of the bigger players in the industry started doing the same. In 2016, the company began outfitting its ships to use power from the grid while tied up in port instead of burning their own fuel—the technology can reduce air pollution when ships are docked by up to 70%. That year, Hurtigruten ordered the world’s first hybrid-power cruise ships, and started offering cruises on its first, the MS Roald Amundsen in 2019, which the company says has about 20% lower emissions than a similarly sized conventional ship. The company now operates four such vessels.

Skjeldam says the changes have to do with both customer desires for more sustainable travel, which he expects to grow in the years ahead, as well as employee demands. Hurtigruten is the largest employer in Longyearbyen, Svalbard’s main settlement. Temperatures there are warming six times faster than the global average, bringing unseasonably hot weather, glacial retreat, and more frequent avalanches triggered by unstable snow. “I speak to these people, and they reflect upon the massive changes that have happened just over the last decade, and it scares them,” says Skjeldam. “That’s driven this interest and desire from within the company on driving change and being part of the solution.”

Hurtigruten is aiming for carbon-neutral operations by 2040, and to cut all scope three emissions—those from the company’s supply chain—by 2050. But despite investing more than $70 million into emissions-reduction technology, progress has been slow, which the company blames partially on energy prices, which made it more expensive to buy low-carbon biofuels. Indeed, while Hurtigruten managed to cut about 2% of overall emissions between 2018 and 2022—emissions per customer trip remained essentially unchanged.

Still, Skjeldam is pushing ahead with the company’s next major project: building the industry’s first entirely zero-emission vessel. In 2021, the team began reaching out to technology firms and shipbuilders, and doing feasibility studies, figuring out what technologies—a small nuclear reactor, perhaps, or maybe using more biofuels—might work. Eventually, they settled on batteries.

There was no way to make a battery that would last long enough to use on what the company calls its “expedition” cruises—where trips vary from week-long pleasure rides the Galapagos to multi-month odysseys between the Arctic and Antarctica, and fares can range from a few thousand dollars to the price of a luxury sports car. But it might work for their flagship service: a multi-stop cruise up the Norwegian coast (which also serves as a mail and transit service between isolated fjord communities) that would offer frequent opportunities to recharge.

Even with many stops, the battery would have to be huge. Currently, the engineers are eyeing a capacity of 60 megawatt-hours, equivalent to 1,200 Tesla Model 3 batteries. This would allow it to run for well over 300 miles before recharging. Maximizing that range means finding ways to drastically cut the ship’s energy usage. To do this, the company is exploring using underwater maneuvering jets that can retract into the hull to cut drag, and a streamlined profile with a tiny cockpit-style bridge to reduce air resistance, as well as adding sails and solar panels to harness extra power. The company plans to have a final design by 2025.

Batteries vs. Biofuels

Hurtigruten’s work may prove out some worthy technologies that the rest of the cruise industry could adopt. But the central idea of using a big battery may ultimately be impossible for bigger cruise ships, because batteries can’t store enough power in a small enough space—to get across an ocean, you’d need a battery that might take up much of an entire ship. Sails can help, but they wouldn’t be able to do more than provide an energy boost for many kinds of shipping. That leaves either biofuels or synthetic fuels produced using renewable energy—each with its own drawbacks.

Methanol, made from renewable energy and CO2, is a good choice, but making it requires obtaining CO2 from a limited supply of global biomass (demand for agricultural waste and other forms of plant-based carbon are set to explode with global demand for alternative fuels) or else using huge amounts of renewable energy to pull CO2 from the atmosphere. Ammonia is another option for the shipping industry, and it gets around the CO2 supply problem, but it wouldn’t work for passenger ships, since a leak would expose thousands of people to poisonous ammonia fumes. Then there’s hydrogen, though the lightest element can be tricky to work with , since it leaks easily and needs to be supercooled to get to high enough densities to transport, which uses a lot of energy.

Four companies—Carnival, Royal Caribbean, Norwegian Cruise Lines, and MSC—control the lion’s share of the cruise market. They’ve made some positive moves, such as investing in ships capable of running on methanol, though such vessels might continue to mostly use diesel for the time being due to lack of refueling infrastructure . But, with the notable exception of Norwegian , the big players’ current environmental plans primarily hinge on using liquified natural gas (LNG) in the newest generation of ships. Using LNG does cut down on particulate emissions and certain dangerous pollutants like sulfur and nitrogen oxides. The industry also cites the fact that LNG has about 30% lower carbon dioxide emissions than using heavy fuel oil. But CO2 isn’t the only thing that escapes from the smokestacks—the engines popular in the cruise industry leave a lot of the natural gas unburned, which gets emitted as well.

Natural gas, also known as methane, is itself a powerful greenhouse gas. With a warming potential more than 80 times greater than CO2 over a 20-year timescale, the overall emissions picture of using LNG is likely worse for global climate change than if the cruise lines had stuck with petroleum.

When asked about the use of LNG on its vessels, a representative for Carnival pointed to the company’s “long term aspirations to achieve net carbon-neutral ship operations by 2050.” MSC Cruises and Royal Caribbean did not respond to requests for comment. “There is [an] abundance of scientific data and well-respected studies that showcase the environmental benefits and value of using LNG, one of the cleanest fuels available today,” the Carnival spokesperson wrote over email. “We also are piloting other next-generation green technologies such as biofuels, fuel cells and large battery storage systems, among others.”

Currently there’s little in the way of regulations to limit greenhouse gasses like CO2 and methane from shipping. Cruise industry emissions fall under the jurisdiction of the International Maritime Organization (IMO) of the United Nations, which technically has the authority to force deep sustained emissions cuts across worldwide shipping. In practice, though, the IMO has historically been heavily influenced by those very interests, with many countries appointing industry representatives to their IMO delegations. And the powerful Cruise Lines International Association (CLIA), the industry’s international lobbying arm, has not exactly fallen over itself to help strengthen emissions standards in ongoing IMO talks on greenhouse gas reductions, according to Bryan Comer, marine shipping program lead at the International Council on Clean Transportation.

“Anything that they can do to try and make the math work in their favor and to not have to do anything is what they’re trying to do at the International Maritime Organization,” says Comer. “They set targets that already include loopholes for them, and then they fight against climate regulations in foreign policy forums, and then once the regulations are agreed, they start fighting for exemptions and adjustment factors and special treatment. And oftentimes they get it.” CLIA representatives did not respond to requests for comment. Hurtigruten is not a member of the organization.

What matters to vacationers?

Some climate activists say there’s a good argument that the cruise industry shouldn’t exist at all. Cruise ships are, on the whole, basically inherently wasteful—if you want to see the world, dragging an entire resort around with you is probably not going to be the most efficient way to do it. Compared to flying to a destination and staying in a hotel, cruising almost always has a far higher emissions profile, according to research by Comer and others . A five-night, 1,200 mile cruise results in about 1,100 lbs of CO2 emissions, according to Comer. Flying the same distance and staying in a hotel would emit less than half of that. And that’s not counting for the fact that cruise guests often also have to fly to the port where they will embark.

Bringing that argument to cruise customers, though, can be an uphill battle. The cruise industry puts a lot of money into defending its environmental image. Activists in cities like Seattle, Wash., and Juneau, Ala., often greet disembarking passengers with leaflets on cruising’s environmental effects. But some campaigners say that passengers are often impervious to volunteers’ arguments. Some passengers, says Karla Hart, an activist with Juneau Cruise Control and co-founder of the Global Cruise Activist Network, will even stop to defend the industry, saying how switching to LNG or phasing out plastic straws has solved cruising’s environmental problem. It’s a symptom, in her view, of a broader dynamic between the cruise industry and its passengers: that customers want to believe they can have the perfect vacations advertised on television and online, even though they know the reality of what they will get is far different.

“It’s a suspension of reality, to go with one’s desire for an experience that you must know you can’t have,” Hart says. “The same as suspending your rational thinking that because they’re not using plastic straws, and they switch to LED lights, that they’re not completely polluting the environment.”

A new TIME survey conducted by The Harris Poll backs up some of those points. To environmental campaigners, cruising stands out as perhaps the most polluting sort of vacation. But fully half of Americans surveyed consider taking a cruise to be “eco-friendly,” with only one in three regarding such vacations as being bad for the environment.

More Americans regard flying as being bad for the environment, despite cruising’s bigger carbon footprint per passenger.

Trying to convince vacationers to make greener choices probably has limited effectiveness anyway. Many Americans consider cruising to be an affordable vacation option—mega cruises especially tend to benefit from economies of scale. Three out of five Americans surveyed by Harris Poll consider cost to be a very important factor in their vacation planning. Meanwhile, only one in five Americans think of the environmental impacts of their vacation in the same way.

Ujwal Arkalgud, who studies consumer decision-making at Lux Research, says that a specialty cruise provider like Hurtigruten might be able to attract customers genuinely interested in sustainability, but that the mass market customers will likely only ever be interested in having a kind of green alibi. “People are not buying to save the planet,” says Arkalgud. “Because you know, one simple way to save the planet would be to not go on the cruise.”

Absent a real push from customers, activists and environmental experts say that only regulation on the level of the IMO, or across enough big ports or markets like the U.S. or the E.U., can make the industry invest in decarbonization in a serious way. “The reason why you’re not seeing a lot of investment and innovation in zero-emission vessels is because it’s a competitive global industry,” says Comer. “If you do something that costs you more, and you’re still competing on price, and you can’t demonstrate to the passenger why they ought to pay more for this, there’s not really any incentive for you to do it.”

Skjeldam supports more regulation—to a certain extent, he says, such measures to limit cruise industry pollution are inevitable. But he also has more faith that cruise-goers actually care about the environment than either activists or other cruise executives. And as the effects of climate change become more pronounced, he says, more of the world’s cruise-buying masses will begin to see the light.

“Unfortunately, there is a misconception in part of the industry, where they don’t think that their guests really are focusing on this. I think that is wrong—I think the guests will focus heavily on it in the future,” Skjeldam says. “The public demands are coming.”

More Must-Reads from TIME

- How Kamala Harris Knocked Donald Trump Off Course

- Introducing TIME's 2024 Latino Leaders

- George Lopez Is Transforming Narratives With Comedy

- How to Make an Argument That’s Actually Persuasive

- What Makes a Friendship Last Forever?

- 33 True Crime Documentaries That Shaped the Genre

- Why Gut Health Issues Are More Common in Women

- The 100 Most Influential People in AI 2024

Write to Alejandro de la Garza at [email protected]

Fraught with environmental baggage, the cruise industry is trying to go green, but is it enough?

The cruise industry has come under fire for its environmental footprint from environmental organizations, and the U.S. Department of Justice has taken up cases against specific lines for environmental violations .

Meanwhile, the cruise industry insists it is making great strides in reducing its environmental impact by implementing new technologies and following or exceeding international guidelines.

One environmental organization, Friends of the Earth (FOE), even released a 2019 "report card" in June, grading each cruise line and its ships. Most received D's and F's. Cruise lines rejected the grades, questioning FOE's methodology.

FOE asserts taking a cruise can be more harmful to the environment and human health than other forms of travel.

So how will cruises go green?

Brian Salerno, senior vice president of maritime policy at Cruise Lines International Association (CLIA), said the industry as a whole has taken steps toward going green both on its own accord and in accordance with the International Maritime Organization's set MARPOL rules, which have been updated over many decades. IMO is an agency of the United Nations.

"This is certainly something that has been a focus of the cruise industry, really even the maritime industry overall," Salerno said.

CLIA, which is the largest trade organization in the cruise industry, has 270 member ships, according to Salerno, who estimated there are more than 300 cruise ships operating around the globe.

“CLIA cruise lines are pioneers in maritime environmental protection and committed to responsible tourism – with policies that often exceed those required by law," CLIA said in a statement.

The initiatives include a commitment from CLIA members to reducing carbon emissions by 40% by 2030 (in comparison to 2008).

"These investments are already showing significant progress towards reducing the environmental impact of the cruise industry, with many more technologies and practices currently under development," the statement continued.

John Kaltenstein, deputy director of oceans and vessels at FOE, said that while the industry is making some small strides, there's a long way to go.

"I think they’ve made strides ... with the use of what we call advanced wastewater treatment systems," Kaltenstein said. The systems have improved filtering and treating grey water.

But for the majority of the industry, there's a long way to go, according to Kaltenstein.

The United States Department of Justice has brought lawsuits against several major cruise lines.

Currently the DOJ has an open case against Princess Cruises. The cruise line and parent Carnival Cruise Lines pleaded guilty for probation violations in June , stemming from a 2017 felony conviction over dumping oil-contaminated waste from one of its ships and intentional acts to cover it up, according to the DOJ.

"The people doing things perfectly, we aren't going to see," Joe Poux, assistant chief in the Environmental Crimes Section of the Environment and Natural Resources Division of the DOJ told USA TODAY.

The cruise lines that are coming to the DOJ's attention on the criminal enforcement side are in scope because something has "not gone well for them."

So with some progress and some missteps by cruise lines, it's a mixed bag in terms of how the industry as a whole is doing.

The cruise industry says it's improving. But is it?

Salerno said that over the last decade, the cruise industry has focused on four areas to reduce cruising's environmental impact, including controlling emissions, sewage treatment, fuel efficiency and recycling.

So are all these areas really evolving in terms of environmental impact? Yes and no, according to CLIA, the DOJ and FOE.

Controlling emissions

"In recent years there's been renewed emphasis placed on what is going into the air," Salerno said.

That includes air pollutants such as sulfur oxide and nitrogen oxide, which can cause respiratory problems. The industry is beginning to control emissions by using an exhaust gas cleaning system (EGCS).

According to CLIA, those systems can reduce sulfur oxide levels by as much as 98% and can reduce nitrogen oxides up to 12%.

As of Jan. 1, the entire shipping world, which includes cruise ships, was required to reduce pollutants by using EGCS, using fuel with a lower sulfur level or using an alternative fuel source.

But according to Kaltenstein, that isn't enough.

The cruise industry is implementing ECGS to be compliant with regulations in the U.S. and on a global scale but instead of using more refined marine fuel, he says they're still using heavy fuel oil and just treating it, which isn't ideal.

Some newer ships are being designed to operate on clean alternative fuels including liquefied natural gas (LNG), which has lower sulfur emissions, Salerno explained.

FOE doesn't see that as a silver bullet solution either.

"Not going to see really any greenhouse gas benefits," said Kaltenstein. "A lot of the environmental community does not see LNG as an answer to the climate problem."

Sewage treatment

"While international law allows for discharge of untreated sewage beyond 12 miles [from the shore], CLIA’s Waste Management Policy prohibits the discharge of untreated sewage at sea anywhere around the world under normal operating conditions," Salerno said.

For those some 270 ships that are a part of the CLIA fleet, compliance with the policy is a condition for membership, he added.

Advanced wastewater treatment systems are installed on all new ships and many older ones, as well. They include advanced filtration and disinfecting technology that exceeds regulatory requirements put in place by the IMO.

"These advanced wastewater treatment systems rival the best systems on land," Salerno said.

Kaltenstein said that in terms of waste, the industry has done better over the last several years. Putting in advanced wastewater treatment systems has been a good step forward.

Fuel efficiency

Cruise lines have made their ships more fuel efficient by implementing a few different tactics, according to CLIA.

They have added air lubrication systems to many ship hulls, which reduce drag and fuel consumption. Those reductions lead to greater efficiency as do energy-efficient engines that consume less fuel.

"Air lubrication systems are a good example of kinds of technology employed on many new ships to reduce fuel consumption," Salerno said. Not all ships have those systems in place yet though.

"When you consider most of them when they're built, you're looking at a 30-year life cycle," he explained. "It pays to put in the most efficient systems that you can. Doing that allows the ship to operate into the future without having to undergo major retrofits. The more efficient you can start out, the better off you are."

Shoreside, ships are also able to "plug in" at ports, which reduces emissions overall.

Like some hotels onshore , cruises have been doing what they can to reduce single-use plastics.

"Many cruise lines have adopted policies against the use of single-use plastic," Salerno said.

One of those lines is Norwegian Cruise Line . It announced last year that it would eliminate single-use plastics in 2020 by partnering with rapper, actor and activist Jaden Smith's JUST Goods Inc. to use paper cartons for water.

The cruise line previously got rid of single-use plastic straws in 2018 across its private islands and resort as well as its 16 ships.

And according to the Miami Herald , Royal Caribbean was looking to replace its more than 65 million plastic utensils with compostable options, along with other reusable options.

Carnival has also said it will take steps to reduce plastic use onboard by stopping balloon drops, using reusable straws and other steps.

Kaltenstein said he believes that the progress away from single-use plastics is a positive step forward for the industry.

"I think to not provision as much in terms of plastic is important; I'd like to see it all be done away with," he said.

One of the issues with plastics, Kaltenstein said, is that the systems for controlling plastic, to make sure it doesn't end up in the ocean, have been breaking down.

"The less you have, the lesser possibility of the materials going into the ocean, one would hope," he explained.

What needs to change?

From the outside looking in, Poux from the DOJ, said it's the corporate culture that needs to change.

Having a judge explain to corporate officers why what is happening on ships with waste is a problem is a "wake-up call" that can "bring in meaningful change," Poux said.

"These are systemic problems," Kaltenstein added. "The only way to address it is to change the corporate culture from the top, to set a mandate."

If a high importance is placed on environmental compliance and making sure that systems are being maintained and used properly to allow the ships to meet standards, then a change is more likely to occur, he added.

MoreUshuaia, Argentina: Cruising to the 'end of the world' and Earth's southernmost city

Cruises: What is wave season? And are these early-season deals really worth it?

Contributing: Adrienne Jordan, David Oliver

- Español (Spanish)

- Français (French)

- Bahasa Indonesia (Indonesian)

- Brasil (Portuguese)

- India (English)

- हिंदी (Hindi)

- Feature Stories

- Explore All

- Subscribe page

- Submissions

- Privacy Policy

- Terms of Use

- Advertising

- Wild Madagascar

- Selva tropicales

- Mongabay.org

- Tropical Forest Network

Cleaning up cruise ships’ environmental wake

Share this article.

If you liked this story, share it with other people.

- For years, campaigners have highlighted the unsustainable practices of the cruise ship industry, including the massive vessels’ dumping of sewage and wastewater, and their emissions of air pollutants and greenhouse gases.

- The cruise industry says it’s working hard to limit its environmental footprint, with the adoption of advanced wastewater treatment systems, cleaner fuels, and other sustainability measures.

- Jurisdictions around the globe have begun tightening rules to limit the effects of visiting ships.

- Critics and advocates remain unconvinced, arguing that much more needs to be done at a far faster pace to tackle cruisers’ global impact on the ocean and air.

In July, Amsterdam became the latest in a series of cities to regulate against huge cruise ships in an attempt to tackle pollution and the burden of overtourism. The Dutch capital joins other cities, such as Venice in Italy, Monterey Bay in California, and Bar Harbor in Maine, in seeking to limit the impact of cruises.

Around the same time, Transport Canada, a national regulator, took its own steps to tackle cruise waste: It upgraded measures that prohibit ship wastewater disposal in the sea from voluntary to mandatory. For years, Canada’s national waters were likened to a “ toilet bowl ” due to lax regulations enabling cruise ships passing through the country’s waters to dump sewage at will, according to campaigners.

“Making the voluntary program into a mandatory one allows enforcement to come in and brings the possibility of fines,” Anna Barford, shipping campaigner for U.S.- and Canada-based NGO Stand.Earth , told Mongabay. She said cruisers dumped as much as 32 billion liters (8.45 billion gallons) of waste in Canadian waters in 2019. “This is absolutely a good and right step.”

Meanwhile, the cruise industry says it’s working hard to limit its environmental footprint across the globe, including greenhouse gas emissions and harm to oceans and air. Critics and advocates argue that much more needs to be done at a far faster pace to tackle cruisers’ global impact.

U.S.-based NGO Friends of the Earth releases an annual scorecard that grades cruise ship companies on their environmental impacts. The most recent, from 2022, looked at 18 major cruise lines, giving the top overall grade, a C+, to a single company. Three others received C-range grades, seven got D-range grades, and seven got the lowest grade: an F. Despite the poor overall scores, some companies are improving when it comes to issues such as air and water pollution, said Marcie Keever, the group’s oceans and vessels program director. But the industry writ large remains mired in harmful activities, underpinned by a general lack of transparency by many players, she said.

“For all the parameters that we look at with our report card on the cruise industry — for all of the big cruise ship companies almost across the board — none of them are doing what they should be doing when it comes to environmental protection and their footprint,” Keever told Mongabay.

Cleaning up waterborne waste

For some time, campaigners have highlighted the dumping of sewage and wastewater as the face of an unsustainable cruise industry.

To tackle the issue, cruise ship owners are installing advanced wastewater treatment systems. Such treatment systems can completely cleanse a ship’s wastewater — from sources such as sinks, showers and toilets — to the point that some of it can be recycled for other on-ship uses, according to Sascha Gill, vice president of sustainability at Cruise Lines International Association (CLIA). The trade group represents the owners of 292 cruise ships, roughly 95% of the global fleet, according to Gill. CLIA member companies served roughly 30 million passengers per year pre-COVID-19.

Of the 264 ships in CLIA members’ fleets whose owners responded to a survey by the association, 202, or 76.5%, are equipped with advanced wastewater treatment systems (28 did not respond). Gill told Mongabay that CLIA members will achieve 100% coverage as older vessels are retired and new ones come with readymade systems installed. He didn’t give a time frame for this transition.

However, critics contend a lack of oversight and transparency persists in the industry when it comes to the treatment facilities’ effectiveness. “We don’t have the details, and we don’t have, which is the most important, independent third-party audits or third-party assessment of technology,” Hrvoje Carić, a researcher at Croatia’s Institute for Tourism, told Mongabay.

Current international regulations, under the International Convention for the Prevention of Pollution from Ships (MARPOL) Annex IV , require ships to have treatment facilities installed, prohibit the discharge of treated sewage within 3 nautical miles (5.6 kilometers) of shore, and prohibit the discharge of untreated sewage within 12 nmi (22 km) of shore. Advocates say illegal dumping continues to occur.

Experts are also concerned that while these advanced systems may offer a high degree of waste treatment, they don’t fix all problems. Maartje Folbert, a Ph.D. researcher in environmental sciences at the Open University of the Netherlands, said that similar to onshore treatment methods, shipboard systems capture contaminants, such as microplastics, but concentrate them in sewage sludge .

“Even though treatment will be quite effective at removing microplastics and other contaminants from wastewater, a large proportion would still end up in the ocean if sewage sludge is discharged overboard,” whether legally or illegally, she said.

In Folbert’s view, simply treating waste isn’t sufficient and companies must take a “broad perspective” on the variety and sources of pollutants to ensure adequate wastewater management. This means considering the fate of substances like microplastics, caffeine and pharmaceuticals that can escape treatment. Potential solutions include transparent regulation of sewage-sludge handling, addressing pollutants at the source by phasing out single-use plastics and products that may contain microplastics, such as cosmetics and cleaning products, applying laundry filters, and improving both the use and availability of port reception facilities to deal with sewage sludge, she said.

Shifting to the air

Air pollution is another significant impact of cruise ships. A report released earlier this year by the Brussels-based NGO Transport & Environment detailed that Europe’s fleet of 218 cruise ships emitted as much sulfur oxide in 2022 as a billion cars. The cruise industry disputes the figure.

To comply with regulations put in place in 2020 under MARPOL that mandate emissions reductions, the industry is building new cruise ships that use alternative fuels , mainly liquefied natural gas (LNG). This offers the potential to reduce pollution and lower CO2 emissions. However, via a process known as “ methane slip ,” this fuel can also exacerbate emissions of this shorter-lived, but more potent greenhouse gas, according to research.

Other efforts to reduce air pollution, such exhaust-gas cleaning systems, also known as scrubbers, can contribute to water contamination. These systems wash seawater through ship exhaust. Open-loop systems send the wash water directly into the sea, and it can be hot, highly acidic and contain a host of pollutants, including particulate matter, polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons, and heavy metals. Closed-loop systems recirculate and continuously treat freshwater, collecting the resulting waste on board for later disposal on shore. Hybrid systems can toggle between open and closed loops.

CLIA states that around 150 ships in its members’ fleets are equipped with scrubbers, of which around one-third are open-loop systems. Their use will be phased out with the switch to new fuels such as LNG, Gill said.

The scrubber problem isn’t confined to cruise ships. A survey by the International Council on Clean Transportation estimates that, worldwide, the shipping industry dumps at least 10 billion metric tons of scrubber wash water into the sea annually; cruise ships account for around 15% of that figure. This can exacerbate ocean acidification, already ramping up with climate change, and directly impact ocean life, including fragile coral reefs, the council’s website states .

According to Stand.Earth’s Barford, the vast majority — around 90% — of wastewater pollution in Canada’s waters is scrubber water. Canada’s newly mandatory regulations don’t touch scrubbers, she said, meaning they don’t address a large portion of pollution. “What we’re asking for is a ban on the use of scrubbers,” she said.

At the global level, regulators should remove an exemption that allows ships to use scrubbers instead of burning low-sulfur fuels, she added. “We know that sulfur in the air is a problem for humans and for wildlife. In the water, it’s also going to cause problems,” she said.

Fast enough?

To reduce cruise ships’ environmental footprint, advocates argue that the industry and regulators must do much more, particularly when it comes to the largest ships.

CLIA’s Gill, however, said international MARPOL regulations are already strict and clear. In addition, future-ready fleets are being fitted with various technologies to tidy themselves up: advanced wastewater treatment systems, onshore electricity connectivity to reduce air pollution in ports, and clean fuels will all become standard, he added.

But advocates, such as Stand.Earth and Friends of the Earth, state that these steps must be taken immediately.

Carić said there’s a further need for “a very transparent and hard look” at the entirety of cruise ships’ environmental impacts, particularly for the largest vessels, via life-cycle assessments. “Governments should involve science in this process,” he said, “not only crews, corporations, and interested stakeholders.”

Banner image: A study published last year in the journal Marine Pollution Bulletin states the cruise industry “remains a major source of air, water (fresh and marine) and land pollution affecting fragile habitats, areas and species, and a potential source of physical and mental human health risks.” Experts say the largest vessels generally have the most significant environmental impacts. Image by Adam Gonzales via Unsplash (Public domain).

Correction 10/7/23: This story was updated to state that cruise ships dumped 32 billion liters, not 32 billion gallons, of waste into Canadian waters in 2019, according to Anna Barford of Stand.Earth. We regret the error.

Ytreberg, E., Hansson, K., Hermansson, A. L., Parsmo, R., Lagerström, M., Jalkanen, J., & Hassellöv, I. (2022). Metal and PAH loads from ships and boats, relative other sources, in the Baltic Sea. Marine Pollution Bulletin , 182 , 113904. doi: 10.1016/j.marpolbul.2022.113904

Folbert, M. E., Corbin, C., & Löhr, A. J. (2022). Sources and leakages of microplastics in cruise ship wastewater. Frontiers in Marine Science , 9 . doi: 10.3389/fmars.2022.900047

Lloret, J., Carreño, A., Carić, H., San, J., & Fleming, L. E. (2021). Environmental and human health impacts of cruise tourism: A review. Marine Pollution Bulletin , 173 , 112979. doi: 10.1016/j.marpolbul.2021.112979

Kotrikla, A. M., Zavantias, A., & Kaloupi, M. (2021). Waste generation and management onboard a cruise ship: A case study. Ocean & Coastal Management , 212 , 105850. doi: 10.1016/j.ocecoaman.2021.105850

Endres, S., Maes, F., Hopkins, F., Houghton, K., Mårtensson, E. M., Oeffner, J., … Turner, D. (2018). A new perspective at the ship-air-sea-Interface: The environmental impacts of exhaust gas scrubber discharge. Frontiers in Marine Science , 5 . doi: 10.3389/fmars.2018.00139

FEEDBACK: Use this form to send a message to the editor of this post. If you want to post a public comment, you can do that at the bottom of the page.

To wipe or to wash? That is the question

Toilet paper: Environmentally impactful, but alternatives are rolling out

Rolling towards circularity? Tracking the trace of tires

Getting the bread: What’s the environmental impact of wheat?

Consumed traces the life cycle of a variety of common consumer products from their origins, across supply chains, and waste streams. The circular economy is an attempt to lessen the pace and impact of consumption through efforts to reduce demand for raw materials by recycling wastes, improve the reusability/durability of products to limit pollution, and […]

Free and open access to credible information

Latest articles.

Maasai women struggle to survive amid forced evictions in conservation area

Wildcat miners: will cyanide displace mercury?

Honduras taps armed forces to eliminate deforestation by 2029. Will it work?

Malaysian court shuts down hydroelectric dam project on Indigenous land

Why I quit the film industry to work on ecological restoration (commentary)

Report links killings to environmental crimes in Peru’s Amazon

Marine ecosystems still overlooked in Indonesia’s new conservation law, critics say

To save endangered trees, researchers in South America recruit an army of fungi

you're currently offline

How the cruise industry is pivoting to sustainability

Cruise ships are notoriously bad for the environment, but this might be changing

- Newsletter sign up Newsletter

The cruise industry is back and booming. By the end of 2023, an estimated 31.5 million passengers will travel on a cruise ship, according to Statista , and that figure exceeds even pre-pandemic numbers. The sector is expected to keep growing exponentially, with Statista estimating nearly 40 million annual cruisers by 2027.

With this uptick, though, comes renewed questions about the cruise industry's negative effect on the environment. Cruise ships are "an environmental disaster," Popular Science reported, with the behemoth ships "having a massive effect on the climate." One study from the University of Exeter showed that the average cruise ship produces the same amount of carbon emissions as 12,000 cars.

While other transportation sectors, like air travel , are working to become more eco-friendly, cruise ships have long been the bane of environmentalists. Groups like Friends of the Earth claim that "everything that cruise ships come in contact with are likely to be harmed along their journey." However, the industry has begun working on alternatives to their fuel-guzzling vessels, and is exploring ways to make voyages by ship both enjoyable and green.

Subscribe to The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

How bad are cruise ships for the environment?

Traditional diesel-powered cruise ships pump out massive quantities of toxic emissions, experts say. While the entire shipping industry emits "2.9% of global carbon dioxide emissions," cruise ships "produce more carbon dioxide annually on average than any other kind of ship due to their air conditioning, heated pools and other hotel amenities," The Associated Press reported, citing a study from the European Federation for Transport and Environment.

Then there are the passengers themselves. A person's carbon footprint " triples in size when taking a cruise," Forbes said, and "the emissions produced can contribute to serious health issues." The scale of cruise ships causes a tremendous amount of garbage to accumulate onboard, and "cruise ships have been caught discarding trash, fuel, and sewage directly into the ocean," Forbes added.

Many resort towns that welcome cruise ships have been directly affected by pollution from the vessels, and there has been a purported rise in medical problems in some of these areas. In the French city of Marseille, for instance, shipping pollution "is estimated to account for up to 10% of the city's air pollution problem," The Guardian reported. One man who lives above the ship-docking area in Marseille has "noticed that the cancer cases here began emerging in the years after the cruise ship boom, as the ships got bigger and more arrived," he told The Guardian.

How are cruise lines reacting?

Many companies within the industry are attempting to pivot to sustainability, and a variety of greener options have been proposed. Nearly every cruise line "is investing in green initiatives, from looking at carbon footprint to refining emissions," Colleen McDaniel, editor-in-chief of Cruise Critic, told CNN .

One of the key aspects of the shift is an attempted move toward alternative fuel sources. Industry trade group Cruise Lines International Association (CLIA) has committed to net-zero carbon emissions by 2050. Two main alternates are battery and hydrogen-powered ships. Despite the well-publicized danger of hydrogen vehicles, "more than 15% of cruise ships debuting in the next five years" will be equipped with hydrogen fuel cells or battery incorporations, CLIA said, with Stanford University professor Marc Jacobsen telling CNN they are "far cleaner solutions" for ships.

Norwegian cruise line Hurtigruten has said it will no longer build fossil fuel-based ships, and is attempting to craft the world's first zero-emission liner. The ship will operate on batteries that "would allow it to run for well over 300 miles before recharging," Time reported. To maximize the ship's range before charging, Hurtigruten "is exploring using underwater maneuvering jets that can retract into the hull to cut drag," and will potentially be "adding sails and solar panels to harness extra power." The company told Time will have a final design for the ship by 2025, with plans to have it water-ready by 2030.

Other initiatives include onboard changes, and "most lines have reduced or eliminated single-use plastics aboard," Travel + Leisure noted. "Waste heat recovery systems are allowing ships like those in the Disney Cruise Line fleet to reduce water usage," the outlet added, and "many cruise lines are also making investments in big-picture sustainability efforts."

Sign up for Today's Best Articles in your inbox

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

Justin Klawans has worked as a staff writer at The Week since 2022. He began his career covering local news before joining Newsweek as a breaking news reporter, where he wrote about politics, national and global affairs, business, crime, sports, film, television and other Hollywood news. Justin has also freelanced for outlets including Collider and United Press International.

The Week Recommends Elizabeth Catlett, Tamara de Lempicka and Marina Abramovic are in the spotlight

By Catherine Garcia, The Week US Published 13 September 24

In the spotlight A sneak peek at how the Supreme Court's decision has panned out

By Theara Coleman, The Week US Published 13 September 24

Instant Opinion Opinion, comment and editorials of the day

By Justin Klawans, The Week US Published 13 September 24

Under the Radar It is estimated that mines will only meet 80% of copper needs by 2030

By Justin Klawans, The Week US Published 12 June 24

Under the Radar But questions remain as to whether they can overtake battery-powered electric cars

By Justin Klawans, The Week US Published 12 March 24

in depth When will it happen, and who will it be?

By Justin Klawans, The Week US Published 15 February 24

The Explainer A growing number of companies in the U.S. are illegally hiring children — and putting them to work in dangerous jobs.

By The Week US Published 30 October 23

Speed Read New cars come with helpful bells and whistles, but also cameras, microphones and sensors that are reporting on everything you do

By Peter Weber Published 9 September 23

Speed Read The pandemic kept people home and now city buildings are vacant

By Devika Rao Published 3 September 23

Speed Read As the industry transitions to EVs, union workers ask for a pay raise and a shorter workweek

By Joel Mathis Published 30 August 23

The Explainer The gap between rich and poor continues to widen in the United States

By Justin Klawans Published 24 August 23

- Contact Future's experts

- Terms and Conditions

- Privacy Policy

- Cookie Policy

- Advertise With Us

The Week is part of Future plc, an international media group and leading digital publisher. Visit our corporate site . © Future US, Inc. Full 7th Floor, 130 West 42nd Street, New York, NY 10036.

Rough seas or smooth sailing? The cruise industry is booming despite environmental concerns

Professor and Director, Ted Rogers School of Hospitality and Tourism Management, Toronto Metropolitan University

Teaching Faculty, Geography and Environmental Studies, Wilfrid Laurier University

Disclosure statement

The authors do not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organization that would benefit from this article, and have disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

Toronto Metropolitan University provides funding as a founding partner of The Conversation CA.

Toronto Metropolitan University provides funding as a member of The Conversation CA-FR.

View all partners

Cruise ship season is officially underway in British Columbia. The season kicked off with the arrival of Norwegian Bliss on April 3 — the first of 318 ships that are scheduled to dock in Victoria this year. Victoria saw a record 970,000 passengers arrive in 2023, with more expected in 2024.

The cruise industry was badly hit by the suspension of cruise operations due to the COVID-19 pandemic in 2020. Fuelled by heavy consumer demand and industry innovation, cruising has made a comeback. It is now one of the fastest-growing sectors, rebounding even faster than international tourism.

While many predicted a difficult recovery , a recent industry report shows a remarkable post-pandemic rebound . Two million more people went on cruises in 2023 versus 2019, with demand predicted to top 35 million in 2024.

But environmental issues plague the sector’s revival. Are they an indication of rough seas ahead? Or will a responsive industry mean smooth sailing?

Cruising has long been criticized for being Janus-faced : on the surface, cruises are convenient, exciting holidays with reputed economic benefits. But lurking underneath are its negative environmental and social impacts .

Unprecedented growth

Newly constructed mega-ships are part of the industry’s unprecedented growth. Royal Caribbean’s Icon of the Seas is the largest cruise ship in the world , with 18 decks, 5,600 passengers and 2,350 crew.

MSC World Europa with 6,700 passengers and 2,100 crew, P&O Arvia with 5,200 passengers and 1,800 crew, and Costa Smeralda with 6,600 passengers and 1,500 crew also claim mega-ship status.

Those sailing to and from Alaska via Victoria will be some of the estimated 700,000 passengers departing Seattle on massive ships three sport fields in length.

Baby boomers represent less than 25 per cent of cruise clientele. Gen X, Millennials and Gen Z have more interest than ever in cruising, with these younger markets being targeted as the future of cruise passengers.

The Cruise Lines International Association asserts that 82 per cent of those who have cruised will cruise again . To entice first-timers and meet the needs of repeat cruisers, companies are offering new itineraries and onboard activities, from simulated skydiving and bumper cars to pickleball and lawn bowling.

Solo cruise travel is also on the rise, and multi-generational family cruise travel is flourishing, explaining the extensive variety of cabin classes, activities and restaurants available on newly constructed and retrofitted ships.

However, only a few cruise ports are large enough to dock mega ships. Cruise lines are responding by offering off-beat experiences and catering more to the distinct desires of travellers.

In doing so, there is a move towards smaller vessels and luxury liners , river cruises and expedition cruising . Leveraging lesser-known ports that can only be accessed via compact luxury ships offers more mission-driven, catered experiences for the eco-minded traveller.

Cruising and environmental costs

Cruise ship visitors are known to negatively impact Marine World Heritage sites. While most sites regulate ballast water and wastewater discharge, there are concerns about ship air emissions and wildlife interactions .

Cruise ship journeys along Canada’s west coast, for example, are leaving behind a trail of toxic waste . A study by environmental organization Friends of the Earth concluded that a cruise tourist generates eight times more carbon emissions per day than a land tourist in Seattle.

Also, a rise in expedition cruising means more negative impacts (long-haul flights to farther ports, less destination management in fragile ecosystems, last chance tourism ) and a rise in carbon dioxide emissions.

Toxic air pollutants from cruise ships around ports are higher than pre-pandemic levels, leaving Europe’s port cities “choking on air pollution .” Last year, Europe’s 218 cruise ships emitted as much sulphur oxides as one billion cars — a high number, considering the introduction of the International Maritime Organization’s sulphur cap in 2020 .

Rough seas ahead or smooth sailing?

Royal Caribbean said its Icon of the Seas is designed to operate 24 per cent more efficiently than the international standard for new ships. International Maritime Organization regulations must be 30 per cent more energy-efficient than those built in 2014.

But despite the industry using liquefied natural gas instead of heavy fuel oil and electric shore power to turn off diesel engines when docking, industry critics still claim the cruise sector is greenwashing . As a result, some cities like Amsterdam, Barcelona and Venice are limiting or banning cruise ships .

Environmental critiques remain strong, especially for polar expeditions . The industry must respond and increase sustainability efforts , but their measures remain reactive (i.e., merely meeting international regulations) rather than proactive. In addition, by sailing their ships under flags of convenience , cruise companies evade taxes and demonstrate an unwillingness to abide by a nation’s environmental, health and labour regulations.

In any case, environmental concerns are escalating along with the industry. Travel agents and industry figures are aware of these impacts and should help promote cruise lines that demonstrate a commitment to sustainable practices.

Local residents need to expect more from port authorities and local governments in order to cope with cruise tourism . Cruise consumers should recognize the environmental costs of cruising, and demand accountability and transparency from cruise lines.

- British Columbia

- Cruise ship

- Cruise liner

- Cruise ships

Want to write?

Write an article and join a growing community of more than 189,800 academics and researchers from 5,044 institutions.

Register now

IMAGES

VIDEO

COMMENTS

Highlights from the industry’s 2024 Environmental Technologies and Practices Report include: Fleet Profile. The CLIA member ocean fleet includes 303 ships and a total capacity of 635,000 lower berths operated by 45 cruise line brands representing 90% of capacity — an increase of 3.6% and 3.34% respectively, compared to the prior year.

According to a recent study published in Marine Pollution Bulletin, a large cruise ship can have a carbon footprint greater than 12,000 cars, while passengers on an Antarctic cruise can produce...

Cruise ships are a catastrophe for the environment — and that’s not an overstatement. They dump toxic waste into our waters, fill the planet with carbon dioxide, and kill marine wildlife. Cruise ships’ environmental impact is never ending, and they continue to get bigger. They once were small ships, around 30,000 tons.

A medium-sized cruise ship spews greenhouse gas emissions equivalent to those of 12,000 cars, while environmentalists accuse big industry players of investing little in decarbonization, and of...

The cruise industry has come under fire for its environmental footprint from environmental organizations, and the U.S. Department of Justice has taken up cases against specific lines for ...

The cruise industry says it’s working hard to limit its environmental footprint, with the adoption of advanced wastewater treatment systems, cleaner fuels, and other sustainability measures. Jurisdictions around the globe have begun tightening rules to limit the effects of visiting ships.

How bad are cruise ships for the environment? Traditional diesel-powered cruise ships pump out massive quantities of toxic emissions, experts say.

The cruise industry transported nearly 30 million passengers and contributed over $154 billion to the global economy pre-pandemic, in 2019; despite the hiccups of the pandemic, it’s on track...

2023 data from Cruise Lines International Association shows investment in technologies and alternative fuels that will accelerate the maritime transition towards net zero.

The cruising industry is two-faced: on the surface, cruises are convenient, exciting holidays with economic benefits. But lurking underneath are its environmental and social impacts.