Tourist Experience in Destinations: Rethinking a Conceptual Framework of Destination Experience

Journal of marketing research and case studies.

Walid BERNAKI and Saida MARSO

Encg, university of abdelmalek essaadi, tangier, morocco, academic editor: esther sleilati, cite this article as: walid bernaki and saida marso (2023), “tourist experience in destinations: rethinking a conceptual framework of destination experience ", journal of marketing research and case studies, vol. 2023 (2023), article id 340232, doi: 10.5171/2023.340232, copyright © 2023. walid bernaki and saida marso. distributed under creative commons attribution 4.0 international cc-by 4.0.

Tourism experience is a genuine source of destination attractiveness and long-lasting competitive advantage. Understanding the main drivers of the tourist experience in destinations is a critical step toward managing and delivering a satisfying destination experience to tourists. However, amidst a stream of research that explores experiences in different service settings, a framework of destination experience remains underexplored. To fill this gap in research, this article aims to draw an integrated conceptual framework of what makes a tourist experience in destinations along the travel journey and depicts the antecedents and consequences. By doing so, DMOs and other tourism stakeholders can fit their marketing strategies to cater to tourists’ needs and preferences. Also, this article discusses several measures and emerging research methods to capture the components of the destination experience.

Introduction

Recently, the concept of customer experience has received renewed attention in the tourism and leisure literature (Godovykh & Tasci, 2020a; Verhulst et al., 2020; Chen et al., 2021; Kim & Seo, 2022). Indeed, many businesses have adopted customer experience management, incorporating the concept of experience into their core objectives (Kundampully et al., 2018). Admittedly, a survey by Gartner (2014) reveals that 89% of companies consider experiences on the front line of their business competitiveness. It is now one of the leading marketing strategies embraced by hospitality firms (e.g., Disneyland, Abercrombie & Fitch, and Starbucks, to name only a few) and tourist destinations (e.g., Morocco, Thailand, Korea, Spain, etc.) (Ketter, 2018). To date, Hudson and Ritchie’s (2009) case study of branding destination experience illustrates this paradigm shift in the marketing and management of destinations. Furthermore, Berry, Carbone, and Haeckel (2002) suggest that organizations that continue to reduce their costs to support lower prices as an alternative to customer experience to gain a competitive advantage may affect the value of their product and service offerings, potentially jeopardizing their competitiveness (Vengesayi, 2003).

Nowadays, all that someone wants when one is on travel is to engage in memorable experiences to satisfy their emotional and psychological benefits, to be part of the destination experience, local culture and people, and country history (Morgan, Elbe, and de Esteban, 2009; Boswijk et al., 2007; Pine & Gilmore, 1999). This suggests that the choice of a particular tourist destination is enhanced by the significant mental image it portrays or the “pre-experience” the tourist expects to have upon arrival rather than the functional and utilitarian benefits that used to consider when making their choices (Oh et al., 2007; Kirillova et al., 2016; Ketter, 2018). Thus, destinations are now challenged to provide experiences that cater to postmodern tourists’ expectations, dazzle their senses, and go beyond alternatives in the marketplace. In this context, providing a conceptual framework of what makes an overall tourist experience in the destination is mandatory for destination marketing to design, manage and deliver a superior experience to tourists as a source of long-lasting competitive advantage (Karayilan & Cetin, 2016; Cetin et al., 2019; Crouch & Ritchie, 2005). In this framework, this study is an attempt to set an integrated conceptual framework of destination experience that depicts the factors of tourist experience during the tourist journey. Notwithstanding, despite the wide stream of research looking at tourist experience in various service settings in destination (Arnould & Thompson, 1993; Quan & Wang, 2004; Vitterso et al., 2004; Prentice et al., 1998), understanding the total experience in destinations is challenging.

This article raises several concerns. The first concern defines the theoretical knowledge of the concept of customer experience in tourism literature. The second concern comprises a conceptual framework of destination experience, including the antecedents, the formation, and the consequences of the tourist experience in destinations. The final concern concludes with marketing and management implications and avenues of future research.

Literature Review

The Customer Experience in Tourism Literature

Since the late 1970s, the concept of experience has been an important research stream in consumer research (Jensen et al., 2015). By recognizing the experiential aspects of consumption, consumption has begun to be seen as an activity of production of meanings and a field of symbolic exchanges (Baudrillard, 1970), encompassed by what Holbrook and Hirschman (1982) call “the experiential view.” In their study, Holbrook and Hirschman (1982) refer to the experience concept as a personal and subjective occurrence with high emotional significance resulting from consuming goods and services. Fundamentally, this experiential perspective questions the limitations of conceptualizing consumption as a need-driven activity, wherein a customer is considered merely a cognitive agent, passive participant, and rational decision-maker that affords no emotions, symbolic, or spiritual relief (Angus, 1989) and focuses only on the quest for information and multi-attribute assessment (Addis & Holbrook, 2001). Against this background, it has replaced this functional and utilitarian view of consumption with an experiential view that emphasizes subjective responses and hedonism in the consumer’s way of thinking and acting (Holbrook & Hirschman, 1982).

Particularly, since the emergence of the experience economy by Pine and Gilmore in 1999, the concept of customer experience has been increasingly cited at the forefront of researchers’ interest, particularly in tourism studies (e.g., Walls et al., 2011; Lugosi & Walls, 2013; Lemon & Verhoef, 2016; Andersson, 2007; Oh et al., 2007), in the same way, the management of customer/tourist experience has received growing attention in the general tourism literature (Schmitt, 2010; Verhoef et al., 2009; Tung & Ritchie, 2011; Brakus, Schmitt, & Zhang, 2008; Adhikari & Bhattacharya, 2016; Meyer & Schwager, 2007; Kundampully et al., 2018). Seemingly, tourism as a concept implies an experience. According to Holbrook and Hirschman (1982), this is explained by the fact that tourist and leisure activities, entertainment, and the arts are inherently defined by symbolic meanings and experiential aspects that make them intriguing research subjects.

Following Kim and Seo (2022), the tourism experience is central to the tourism and hospitality industry and the main determinant of tourists’ behavioral intention and decision-making (Huseynov et al., 2020; Shafiee et al., 2021; Klaus & Maklan, 2013). To date, many studies in tourism literature have described the prevalence of tourists’ emotions and their strong influence on service performance and tourists’ behavioral intentions, such as willingness to recommend and spread positive word-of-mouth (Godovykh & Tasci, 2020b; Verhulst et al., 2020; Hosany et al., 2015).

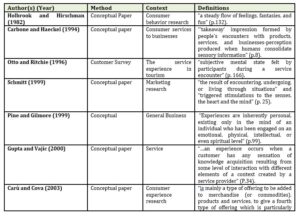

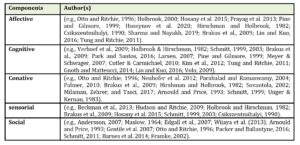

In the literature, more studies have exemplified an exhaustive and perplexing set of definitions and theoretical meanings of the experience construct (see table 1). Furthermore, numerous components emerge in the literature (e.g., affective, cognitive, conative, sensorial, and social), raising difficulties for academics and practitioners to fathom the concept of tourist experience (see table 2). These above components reflect a holistic structure of the destination’s positive and compelling tourism experiences (Godovykh & Tasci, 2020a).

Interestingly, the concept of customer experience has been approached primarily as a subjective, affective, and personal reaction to an event, market stimulus, or activity at different phases of the consumption process. For example, Otto and Ritchie (1996) define tourist experience as “the subjective mental state felt by participants during a service encounter” (p. 166). In their ground-breaking work, the authors claim that affective or emotion-based reports—i.e., the subjective, individual, and feelings experienced by tourists while traveling, are typically substantial in consumer behavior and marketing research. However, in conventional analysis, they are often neglected in explaining variances in tourists’ satisfaction evaluations, thereby limiting the understanding of consumer behavior. In addition, Schmitt (1999) considers customer experiences as “the private events that occur in response to stimulation (e.g., as provided by marketing efforts before and after purchase). They often result from direct observation and/or participation in events-whether they are real, dreamlike, or virtual” (p. 60). Also, Packer and Ballantyne (2016) refer to tourist experience as an individual’s immediate or ongoing, subjective, and personal reactions to an event, activity, or occurrence that usually happens outside one’s daily routine and familiar environment.

In anthropological and ethnological studies, experience is an individual’s expression of their own living culture (Bruner, 1986). In conceptual terms, customer experience differs from an event. While an event happens to others, to society, and to the world, an experience is unique, personal, and differs from one person to another (Abrahams, 1986, as cited in Carù and Cova, 2003, p. 270).

From a broader perspective, Verhoef et al. (2009) suggest that customer experience is more than the result of a single encounter; it is affected by every episode of the customer’s interaction process with a firm. This is in line with Larsen (2007), who argues that the tourist experience cannot be conceived simply as the various events that arise during a tourist visitation but as an accumulation of ongoing travel stages (e.g., pre-trip expectations, events at the destination, and post-visitation consequences). This implies that the experience occurs before the event or any other service and may last long after the experience (Gretzel & Jamal, 2009; Arnould, Price, & Zinkha, 2002; Lugosi & Walls, 2013). Accordingly, these mutual influences continue to affect tourists’ future behavior and expectations for the next journey (Godovykh & Tasci, 2020a). In this regard, some scholars, like Walls (2014) and Carbone and Haeckel (1994), shed light on experience as the “takeaway” impression or outcome people generate during their encounters with organizations’ products or services. For instance, Park and Santos’s (2016) investigation of the memorable experience of Korean backpackers states that the remembered experience is critical when determining future behavior and decision-making. The latter falls within the experience economy, wherein Pine and Gilmore (1999) submit that experience memorability captures customers’ hearts.

From a management and marketing standpoint, experience is seen as a novel and distinctive economic product that can be acquired as a separate good or service that satisfies postmodern consumer needs (Pine & Gilmore, 1999). As a result, the creation of an immersive backdrop for customers is now considered by the marketing discipline known as experiential marketing (Schmitt, 1999). According to Carù and Cova (2003), an experience is “mainly a type of offering to be added to merchandise (or commodities), products and services, to give the fourth type of offering which is particularly suited to the needs of the postmodern consumer” (p. 272). As an offering, experience has become closely related to a trip, journey, or even the attraction itself (Volo, 2009). Admittedly, an experience is created when “a company intentionally uses services as the stage and goods as props, to engage individual customers in a way that creates a memorable event” (Pine & Gilmore, 1999, p.11). That is, experiences are not self-generated but occur in response to staged modalities and the environment (Schmitt, 1999). Palmer (2010), in his conceptualization of customer experience in a retail setting, stated that it implies a variety of market stimuli that hold the potential to create value for customers. These stimuli are viewed as external factors that give birth to the experience.

Furthermore, Meyer and Schwager (2007) contend that contact with the service provider, whether direct or indirect, affects the customer’s experience. Direct contact occurs when a product or service is purchased, used, or provided. In contrast, indirect contact refers to unplanned encounters with service providers and touch-points that may entail reputation, a recommendation, advertising, after-sales support, and other factors (e.g., Payne et al., 2008). This shows that factors outside of an organization’s control, as well as those inside its control, have an impact on the customer experience (Verhoef et al., 2009).

In recent studies, in an attempt to define an all-comprehensive definition of the construct of experience, Lemon and Verhoef (2016) defined the concept of customer experience as “a customer’s cognitive, emotional, behavioral, sensorial, and social responses to a firm’s offerings during the customer’s entire purchase journey” (P.70). In this perspective, Bagdare and Jain (2013) refer to customer experience as all-inclusive and define it as “the sum total of cognitive, emotional, sensorial, and behavioral responses produced during the entire buying process, involving an integrated series of interaction with people, objects, processes, and environment in retailing” (p. 792). These definitions embrace the cognitive, emotional, sensory, and behavioral components of experience produced in the frame of different interactions with customers, stakeholders, and management processes. Generally speaking, managers and marketers have found it challenging to understand the relevance of the notion of the tourist experience and to identify the various interactions and relationships between customers/tourists and destination elements.

Table 1: An overview of definitions regarding the concept of customer/tourist experience

Table 2: Components of the concept of customer/tourist experience

The Value of Tourism Experience in Tourist Destinations:

Nowadays, with the increasing worldwide competition and the changing situation the world lives in due mainly to the post-pandemic period, the global economic crisis, and the emergence of a new form of technologies and behaviors, tourist destinations are not spared from these challenges. To adapt to these changes and maintain their position in the market, the tourism industry players need to develop and reinvent their tourism. Understanding their experiential offerings is therefore prominent to accomplish this. According to Pine and Gilmore (1999), the core value of destinations lies in the quality of the experience it offers. This experience can be strong that tourists might develop a deep emotional bond with their travel destination (Hidalgo & Hernandez, 2001) and influence their behavioral intentions (Prayag et al., 2017; del Bosque & San Martin, 2008). Nevertheless, limited studies address a comprehensive framework of what makes an overall tourist experience in the destination or implicitly depict the antecedents, formations, and consequences of the tourist experience in the destination (Cetin et al., 2019; Karayilan & Cetin, 2016). It is, therefore, within this context where this conceptual paper is located.

More specifically, within the context of tourist destinations, everything a “tourist goes through at a destination is an experience, be it behavioral or perceptual, cognitive or emotional, expressed or implied” (Oh et al., 2007, p. 120). Stated in another way, the destination elements, such as natural and cultural assets, spectacular scenery, and friendly local people, are no longer sufficient to satisfy the contemporary tourists’ needs and differentiate places in a highly competitive market (Hudson & Ritchie, 2009; Ketter, 2018). Instead, by providing a satisfying destination experience, destination managers and policy-makers can set their offering apart from their competitors (Schmitt, 2010), enhancing destination desirability to tourists and increasing, in return, destination profitability (Morgan, Elbe, and de Esteban, 2009; Lugosi and Walls, 2013).

To date, a great deal of research has explored experiences in specific settings, such as food experience (Quan & Wang, 2004), tourist attractions (Vitterso et al., 2000), backpackers (Park & Santos, 2016), heritage parks (Prentice et al., 1998), to name only a few. However, while these studies concentrate on a specific type of tourism experience, few studies have thoroughly approached the factors that holistically drive the tourism experience in destinations. The reality is, regarding the lack of a clear definition of the concept per se, the subjective nature of the construct, the timeframe of the experience, the dynamic nature of the destination itself, and the diverse approaches to the tourist experience are among the factors that make capturing the critical drivers of destination experience a difficult task (Godovykh & Tasci, 2020a).

Since the tourism experience extends a period of time and simultaneously involves synergistic interactions and consumption of products and services, destination managers cannot wholly orchestrate the drivers of the tourist experience in the destination (Lugosi & Walls, 2013; Walls et al., 2011). At best, they can only influence the psychological environment and the prerequisite that facilitate the conditions for the experience to take place (Mossberg, 2007). According to Lugosi and Walls (2013), experiences are a flow of emotions and thoughts that occur during destination encounters, including the influence of the physical environment (e.g., atmospherics, infrastructure, and superstructure), the social environment (e.g., the local community), and other customers (e.g., fellow tourists, friends and relatives). This is because a tourist’s experience entails a series of engagements and interactions with the tourism industry, meanings, and people’s surroundings (Moscardo, 2003). This interplay of interactions represents the core of the overall destination experience (Karayilan & Cetin, 2016). Within this analysis, the tourist experience can be regarded as a compound construct that originates from a set of interactions between tourists’ internal factors, such as cognition and senses; and an organization’s external factors, such as the physical environment, other tourists, employees, local communities, and tourism operators (Adhikari & Bhattacharya, 2016; Albayrak et al., 2018).

The Co-creation Perspective in Tourism Experience

In the last decade, consumer research has witnessed an ongoing period of changes in its theoretical and philosophical foundations. The framework within which the debates have been conducted is labelled “modernism versus postmodernism” (Featherstone, 1988; Firat, 1990; Firat & Venkatesh, 1993; Hirschman & Holbrook, 1992; Turner & Turner, 1990; Firat & Venkatesh, 1995; Fırat & Dholakia, 2006; Cova & Cova, 2009). The starting point of the first reflection is none other than the consumer who has changed status and even multiplied his functions and roles about the meanings he attributes to his consumption. Specifically, customers (e.g., tourists) have become less concerned about the material values of consumption and more interested in the experiential value they derive from activities and products (Firat & Dholakia, 2006). Arguably, Tarssanen and Kylänen (2006) put forward that the value in tourism activities is accumulated by means of more experiential elements and active participation, as opposed to simply visiting a particular tourist destination. Under this approach, Saraniemi and Kylänen (2011) consider the destination a dynamic entity where the tourist can “jump in.” Meaning that tourists are willing to co-create value with destination providers. For instance, Wu et al. (2015) argue that participatory experiences influence tourists’ perception of and satisfaction with their salt tourism experience.

Building on this theoretical analysis, the idea that the tourist experience is only determined by the industry and carried out by passive customers is contested in light of this theoretical approach. For example, Walls et al. (2011) proceed to argue that an experience is “self-generated and that the customer can control or choose whether he will have an experience or not (including negative experiences)” (p. 18). This is consistent with extant research, implying that tourists recall what they perform rather than what they see (Park & Santos, 2016). In fact, tourists form their own experiential space that fits their vision for what it should be, depending on their motivation and reasoning (Suvantola, 2002). This is why King (2002) explicitly notes that “customers interested in travel and tourism have an enormous range of experiences and destination options open to them, but they are increasingly in the driving seat when it comes to how they uptake their planning information, what they receive and the process they choose to go through in marketing their purchase” (p. 106). For this reason, many studies have emerged to recognize the modifying role of tourists in the creation and design process because the value of service and product offerings rely on tourists’ active participation in the consumption process.

Indeed, with the democratization of the Internet and the growing use of information and communication technologies (ICTs), Neuhofer et al. (2012) posit that tourists have become active participants in creating the experience they want to live in. Following these developments, Prahalad and Ramaswamy (2004) assign tourists as co-creators of their own experiences. They presume that the value creation of destinations depends on the ability of destination management processes to facilitate tourists’ interactions within the tourism system, which allows tourists to personalize their own experiences. Thus, by leaving space for tourists, Richards and Wilson (2006) imply that such an approach can lead tourists to construct their trip narrative of their surroundings and form their personal perspective.

In this context, Ritchie and Hudson (2009) exhort marketers to concentrate their marketing actions and advertising on tourism experiences to evoke tourists’ senses and inspire them to co-create their experiences while co-constructing the meanings they are looking for (Cova, 1996). Similar to this, Scott et al. (2009) propose, for future research, a shift from experience as something inherent for the visitor to a management approach in which experience is co-created by the visitor and supplier. In summary, it can be concluded that a tourist experience is highly personal, subjective, and co-created by tourists and providers through a series of interactions with the physical environment and activities, tourism businesses, and other fellow tourists.

Measurement of Experience and the Emergence of New Research Method

One of the most difficult and crucial problems for any destination or organization looking to establish a sustainable competitive edge is understanding the components of tourist experiences in the destination and managing all clues during tourists’ interactions with destination service providers (Lemon & Verhoef, 2016; Becker & Jaakkola, 2020). Indeed, by understanding the key factors of the tourist experience, managers and marketers can respond to the needs of potential tourists and influence their behavior.

However, academics and practitioners suffer from measurement myopia because the tourist/customer experience is individualized, vague, and multifaceted. Our analysis of prior research generally brings forth the core tenants of measurement complexities and challenges as follows: these complexities include a lack of an accepted definition of the concept, the multiple elements that underpin the construct in itself, the dynamic nature of the context-specific variables, the intangible nature of tourism products and services, the highly subjective, unique, and personal reactions of tourists, and the number of tourism players and stakeholders that exist within the tourism system (Godovykh & Tasci, 2020b; Hwang & Seo, 2016; Gentile et al., 2007; Meyer & Schwager, 2007; Palmer, 2010; Bagdare & Jain, 2013; Gnoth & Matteucci, 2014).

One degree of complexity arises from the fact that tourists differ in their motivations, attitudes, travel behavior, and preferences (Kundampully et al., 2018). For example, Andersson (2007) and Morgan et al. (2009) affirm that the expected value of a particular experience may differ from that of others. Similarly, Hwang and Seo (2016) suggest that the consumption experience might easily change the affective attitude generated by a customer experience over time. Furthermore, Csikszentmihalyi and Csikszentmihalyi (1988) argue that some personal characteristics may influence customers to engage in “flow” experiences more frequently, more intensely, and longer than others. Similarly, Ritchie and Hudson (2009) argue that tourists bring different social and cultural backgrounds; that is, each tourist holds a specific personal value that filters through their lives and affects their decision to select a particular destination and tourism experience (Madrigal & Kahle, 1994). Furthermore, Milman et al. (2017) report that visitor experience dimensions might not be concrete or objective when visiting a mountain attraction. This may induce different attributes and yield different interpretations, which vary from one customer to another.

Other scholars refer to the broad spectrum of research methodologies that have emerged in the business field and might be adjusted to investigate the concept of customer experience in the tourism and hospitality industry. These research methodologies are heterogeneous to the extent that customer experience is measured either quantitatively or qualitatively using a wide range of measurement tools, such as structured surveys, direct observation, structured or unstructured interviews, and measurement scales. Nevertheless, most researchers fail to consider the drivers of customer experience in its totality, for example, in pre-, during-, and post-experience (Godovykh & Tasci, 2020a). For example, many scholars (Verhulst et al., 2020; Godovykh & Tasci, 2020b; Kuppelwieser & Klaus, 2019; Palmer, 2010) have questioned the substantial reliance on conventional and retrospective self-report metrics to capture the dynamic aspects of tourists’ emotional responses from past experiences and current customers’ feelings, ignoring the dynamic nature of affective dimensions of experience. Accordingly, this may not predict consumer behavior or service performance outcomes. In this context, the online experiment by Godovykh and Tasci (2020b) supports the significant impact of post-visit emotional stimulation on several aspects of customer loyalty, demonstrating that the dynamic nature of the customer experience can be altered even long after the customer journey.

On the other hand, many scholars note a shortage of innovation-related methods to identify the key elements of the tourist experience and the inability of many researchers to convey theory to research methods. For example, Palmer (2010) deems the inadequacy of survey design to assess the changing nature of affective and experiential dimensions of experience and, adding to the above, the concern that respondents’ answers might be misrepresented by their mood when answering questions (Skard et al., 2011); alternatively, it can be biased to the fact that they may not recall experienced emotions accurately.

In this regard, Fick and Ritchie (1991) advocate using additional qualitative measures to abstract critical dimensions and highlight that a strictly quantitative scale fails to consider those affective and hedonic factors “which contribute to the overall quality of the service experience” (p. 9). From this point of view, Ritchie and Hudson (2009) argue that qualitative methods are convenient for researchers. For example, Holbrook (2006) surmises that due to the context-specific and non-linear nature of experiences, qualitative methods are well-suited to assess customer experience. Godovykh and Tasci (2020b) draw attention to more psychophysiological measures of emotions, such as electrodermal activity and electromyography, electrocardiography, pupillometry, etc., to overcome the limitations of conventional self-report measures. Correspondingly, Verhulst et al. (2020) adopt neurophysiological metrics to measure emotions and their dynamic nature along with customer experience. Their experimental results show that neurophysiological measures may better delineate arousal levels throughout different customer experience phases, although not self-reported by participants. Thus, Verhulst et al. (2020) emphasize the critical stake of such measures to managers and service designers, as they depict how emotions vary across different touch-points and channels throughout the customer experience. Hence, such a measurement approach might underpin which moments better predict customer behavioral intentions and service performance outcomes. However, using neurophysiological methods for data analysis is more difficult and costly for analyzing; therefore, managers and academics may reject it (Verhulst et al., 2019).

Hwang and Seo (2016) propose innovative methodologies to approach customer experience and recommend using experience sampling, grid techniques, netnography, structured content analysis, and emphasizing a cultural perspective. According to Lugosi and Walls (2013), a wide range of approaches and methods have been provided to studies regarding destination experiences, such as autoethnographic, ethnographic, visual methods, netnographics, and other forms of Internet research approaches, along with more traditional survey-based and quantitative approaches (see also, Hosany & Gilbert, 2010; Oh et al., 2007; Raikkonen & Honkanen, 2013). In accordance with Godovykh and Tasci (2020a), capturing the fundamental nature of tourist experiences must call upon a mixture of different research approaches, including self-report methods, interview techniques, experience sampling methods, and psychophysiological metrics, to allow researchers to instantly measure components of the total experience and respondents’ reactions as they unfold before, during, and after the experience, as opposed to looking only at transactional touch-points. Kim and Seo (2022) confirm that a combination of such methodologies reflects the true nature of customer experience. Similarly, Klaus and Maklan (2013) assert that quality of service experience (EXQ) should be considered alongside more traditional metrics for measuring customer experience. For example, customer satisfaction and net promoter score are commonly known as better and direct predictors of customer behavior, and their applicability is relatively practical and cost-effective. In general terms, Verhulst et al. (2020) and Verhulst et al. (2019) posit combining neurophysiological measures with conventional metrics (e.g., self-report and behavioral measures), which may help to strengthen validity and reliability.

Last but not least, in light of the development of ICTs, Lugosi and Walls (2013) claim that hardwired technologies, such as mobile phones, GPS, and geographic information systems, have lately gained more ground in the investigation of daily tourist movements and activities in a location.

For example, Lee et al. (1994) employed a self-initiated tape-recording model (SITRM) to gather data. This technique requires participants to wear electronic pagers and carry self-report booklets in addition to a quantitative survey form, making researchers more willing to collect immediate participant experiences. In doing so, it minimizes memory decay and mood bias. Volo (2009) sheds light on the benefits of unobtrusive methods (e.g., sensory devices, use of GPS, travel diaries, and videos) as an alternative to access tourists’ emotions and feelings. Chen (2008) examined travelers’ mental representations of their family holiday experiences and actions using the Zaltman metaphor elicitation technique (ZMET). Supplementing this approach, Lugosi and Walls (2013) recommend adopting the actor-network theory (ANT) technique to examine travel destinations and visitor experiences through various players, actions, processes, and relationships as a complement to this strategy. Kim and Seo (2022) provide insight into new big data sources for gathering information on consumer experience.

An Integrated Conceptual Framework of Destination Experience

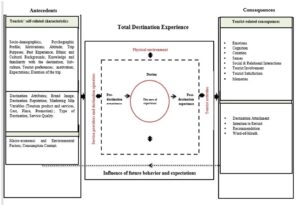

Tourist Experience is a complex and wide-ranging construct arising from a broader set of interactions with actors, stakeholders, and other tourists (Jaakola et al., 2015; Verhoef et al., 2009; Packer & Ballantyne, 2016; Kandampully et al., 2018; Meyer & Schwager, 2007). In light of the above discussion, many studies refer to the tourism experience as cumulative of each moment experienced by tourists during their journey, i.e., before the experience occurs, during the travel destination, and long after the tourist returns to their home environment. This ongoing process influences tourists’ future behavior and expectations of the next trip. To illustrate, Tung and Ritchie (2011) define an experience as “an individual’s subjective evaluation and undergoing (i.e., affective, cognitive, and behavioral) of events related to their tourist activities that begin before (i.e., planning and preparation), during (i.e., at the destination), and after the trip (i.e., recollection)” (p. 1369). Thus, different factors influencing tourist behavior can be illuminated during each stage of the experience process (Chen et al., 2014). Still, no prior holistic conceptual model exists in the literature that has examined all the elements that form the tourist experience in the destination.

Our approach to the present study is to build on the initial work of Godovykh and Tasci (2020a), Lugosi and Walls (2013), and Walls et al. (2011), an integrated conceptual framework of destination experience (see Figure 1). This conceptual framework portrays a process that covers components, processes, and stakeholders and depicts how they combine to form what is fundamentally the destination experience. It takes the tourist experience antecedents from a diverse body of literature and deals with tourist experience as a construct created due to tourist interactions with the physical and social environment of the destination along their journey (i.e., pre, during, and post-destination experience), creating, in consequence, opportunities for positive outcomes to tourists and destinations as well.

From a marketing perspective, this framework is suggested as a tool for decision-making to help DMOs and other tourism stakeholders to capture the holistic nature of the tourist experience in the destination setting. This may have practical implications for DMOs and other tourism stakeholders operating at the destination to fit their marketing practices to design a superior destination experience in response to the tourists’ needs and preferences. Practically, future research on tourist experience in destinations may pinpoint the specific roles of each stakeholder and the destination elements when considering the construction of the experience the tourists receive.

In doing so, we consider the definition proposed by Godovykh and Tasci (2020a), which is holistic from its perspective, to explain the concept of the destination experience. We include the social interaction dimension as a crucial element of the tourist experience in the definition mentioned above in order to widen the scope of experiential appeal and dwell on the implications of developing an integrated destination experience (see the works of Murphy, 2001; Milman, Zehrer, & Tasci, 2017; Bharwani & Jauhari, 2013).

In this perspective, a destination experience can be described as the total of tourists’ internal reactions (i.e., affective, cognitive, sensory, conative, and social) enhanced by external destination-related elements (e.g., destination stakeholders and managers, physical environment, tourism activities, local community, and other tourists) that occur within a series of dynamic interactions encountered directly or indirectly along the travel journey; during pre- destination experience, during the core of the experience and post-destination experience. As a result, it might be interpreted differently according to tourists’ characteristics, resulting in distinct consequences related to tourists and the visited destination. This proposed definition may be particularly constructive in explaining and measuring destination experience. It describes the holistic structure of experience components (e.g., cognitive, affective, sensorial, conative, and social) as tourist responses during their journey. Accordingly, this proposed definition is highly consistent with previous conceptualizations of other tourism and hospitality scholars (e.g., Packer and Ballantyne, 2016; Adhikari & Bhattacharya, 2016; Palmer, 2010; Verhoef et al., 2009).

Antecedents

In the tourism and hospitality industry, a number of antecedents have been offered as reliable predictors of customer experience, some of which have been argued to affect the quality, formation somewhat, and/or purchasing of experiences. This is due to the fact that each tourist’s experiences are unique based on their perceptions, consumption, and interpretation.

One set of antecedents is related to tourists’ characteristics in terms of socio-demographics (gender, age, nationality, occupation, salary), psychographic profile (personality and lifestyle), and culture (Godovykh & Tasci, 2020a; Adhikari & Bhattacharya 2016; Kim et al., 2012; Andersson, 2007; Hwang & Seo, 2016; Park & Santos, 2016; Morgan, Elbe, & de Esteban. 2009), level of familiarity, knowledge and previous experience background (Holbrook & Hirschman, 1982; Finsterwalder & Kuppelwieser, 2011; Adhikari & Bhattacharya, 2016; Hwang & Seo, 2016), group characteristics and ethnic background (Holbrook & Hirschman, 1982; Adhikari & Bhattacharya, 2016; Hwang & Seo, 2016; Heywood, 1987), tourists’ expectations (Arnould and Price, 1993; Ofir & Simonson, 2007), their preferences and purposes of trips (Adhikari et al., 2013; Hu & Ritchie, 1993; Wijaya et al., 2013), skills, abilities, and attitudes (Andersson, 2007), and tourist motivation and level of involvement (Prebensen et al., 2013). Such factors are critical drivers of one’s experience at the destination and post-purchase experience evaluation.

The other set of antecedents is concerned with destination-related features and situational characteristics. On the one hand, most researchers claim that destination attractions represent the core elements of tourism (Gunn, 1972). Furthermore, Buhalis (2000) reports that tourists’ selection of a particular destination is motivated by existing tourism attractions, accessibility, available packages, activities, and ancillary services. Similarly, Lin and Kuo (2016) suggest that the destination’s culture, history, religion, nature, events, architecture, hospitality, and other related variables likely influence the tourist experience. Also, Mossberg (2007) suggests many factors influencing the tourist experience, i.e., service personnel, physical environment, products/souvenirs, other tourists, and themes/stories. More broadly, Kim (2014) proposes ten factors to form memorable tourism experiences, including local culture, various activities, hospitality, infrastructure, environment, management, accessibility, quality of service, physiography, place attachment, and superstructure. From another perspective, marketing literature considers that tourist behavior depends heavily on the nature and quality of the tourism experience. For example, Gronroos (2001) highlights the significant determinants of service quality on customer satisfaction, behavioral intentions, and customer experience. On the other hand, situational characteristics include situational factors, such as the nature of the consumption context (Hwang & Seo, 2016) and macroeconomic and environmental factors (Grewal, Levy & Kumar, 2009; Hwang & Seo, 2016; Hudson & Ritchie, 2009) that likely influence the tourist experience in various contexts. The tourist and hospitality business as a whole has undoubtedly been impacted by several uncontrolled factors, such as natural disasters and climate change, financial crises, unfavorable exchange rates, and sanitary concerns.

Consequences

The concept of experience is central to customer behavior (Klaus & Maklan, 2013; Addis & Holbrook, 2001). Many studies have discussed the positive relationship between positive tourist experiences and behavioral intentions and attitudes to make inferences about the destination.

From a tourist perspective, as mentioned before, experiential responses have broadly been expressed as a combination of cognitive, emotional, behavioral, sensorial, and social reactions by a tourist as a result of active interactions and engagement with the destination’s physical environment, people, and tourism stakeholders. In this regard, the tourism experience is proposed to result in emotional responses such as fun, feelings, fantasies, entertainment, and refreshment (Holbrook & Hirschman, 1982; Hirschman & Holbrook, 1982; Holbrook, 2000; Tynan & McKechnie, 2009; Hwang & Seo, 2016; Babin et al., 1994); cognitive responses such as knowledge, skills, learning, and memories (Oh et al. 2007; Holbrook & Hirschman, 1982; Pine & Gilmore, 1999; Lin & Kuo, 2016); conative responses such as practices, involvement, and engagement (Palmer, 2010; Schmitt, 1999; Unger & Kernan, 1983; Kim et al., 2012; Prahalad & Ramaswamy, 2004); sensorial responses such as taste, sound, smell, sight, and touch (Berry, Carbone, and Haeckel, 2002; Hudson & Ritchie, 2009); and perceived motivation (Pearce & Caltabiano, 1983; Oh et al., 2007). In a nutshell, when tourists value the experience, they begin valuing everything they feel, hear, see, and smell during their encounters with the destination.

From a destination perspective, DMOs can meet tourists’ expectations and sway their behavioral intentions in terms of satisfaction and behavioral loyalty intentions by having an understanding of how tourists evaluate and benefit from their experiences at the destination (Klaus & Maklan, 2013; Hosany & Gilbert, 2010). According to Oppermann (2000), travelers’ positive experiences at a destination may affect their desire to return and strengthen their ability to recommend the destination to friends and family. Hidalgo and Hernandez (2001) argue that experiences might be so powerful that tourists might become attached to the destination. These marketing outcomes are based on the importance of literature and research, emphasizing their weight as a consequence (Godovykh & Tasci, 2020b).

Figure 1: A conceptual framework of total destination experience

Conclusions, Implications, and Future Research Perspectives

This study aims to develop an integrated conceptual framework of tourist experiences in the destination based on the theoretical and conceptual understanding of tourism experience as an emerging topic in tourism research and consumer behavior. This framework will assist DMOs and policy-makers in broadening their understanding of the various factors and processes when considering the formation of the tourism experience. In doing so, DMOs and other tourism stakeholders can manage the prerequisite of enjoyable experiences for tourists, which will likely inspire tourists to return to the destination and recommend it to others.

The relevance of this research lies in the topicality of experience themes in tourism studies; the different insight that stems from this conceptual paper might have theoretical and managerial implications. From a theoretical perspective, this study aims to extend the conceptual and theoretical investigations of the experiential paradigm for destination management and marketing (Lugosi and Walls, 2013; King, 2002; Morgan, Elbe, and de Esteban, 2009). Therefore, the conceptual framework supplements the traditional framework of management through an experiential approach that considers the neglected experiential reactions of tourists (i.e., affective, conative, sensorial, and social responses) evoked as a result of dynamic interactions and active engagement with destination elements and stakeholders, alongside their destination visitation. From a management and marketing perspective, we believe that the conceptual framework of destination experience management may function as a guideline framework for destination managers and marketers to empirically study tourist experiences during the tourist journey in a destination. Hence, a clearer understanding of the relationship between specific tourist experiences, as they relate to the destination, can signal destination managers and marketers to establish a well-conceived marketing strategy to stage and deliver the desired tourism experience as part of a tourist value proposition.

Recently, intensive work has shed light on the co-creation experience process as critical to marketing strategies and differentiation in the general business literature. From this perspective, tourists are no longer considered passive recipients of a pre-conceived tourism product or experience but rather active partners in the co-creation experience design and management process (Lusch & Vargo, 2006; Lugosi and Walls, 2013; Prahalad & Ramaswamy, 2003; Mossberg, 2007; Binkhorst & Den Dekker, 2009). Morgan, Elbe, and de Esteban (2009) imply that the delivery of co-creation tourist experiences can only be achieved through an effective combined effort between the private and public sectors. This is in line with previous research that considers tourist experiences derived from broader networks of actors, stakeholders, tourists, suppliers, host guests, brands, fellow tourists, and the local community (Jaakola et al., 2015; Verleye, 2015). Therefore, destination managers and marketers must focus on an eco-tourism system that includes destination managers and stakeholders in managing the co-creation destination experience. Therefore, further investigations are required to design co-creating experiential marketing strategies to assist tourists in co-constructing their desired tourism experience that provides the emotional state or pre-image they are looking to live in.

Last but not least, we propose empirical studies investigating causal linkages between different variables with related interactions, antecedents and consequences to fully leverage the relevance of the proposed conceptual framework.

Statements and Declarations

The author(s) reported no potential conflicts of interest.

The author(s) received no financial support for this article.

- Abbott, L. (1955). Quality and competition. Columbia University Press.

- Addis, M., & Holbrook, M. B. (2001). On the conceptual link between mass customisation and experiential consumption: An explosion of subjectivity. Journal of Consumer Behaviour: An International Research Review, 1(1), 50–66.

- Adhikari, A., Basu, A., & Raj, S. P. (2013). Pricing of experience products under consumer heterogeneity. International Journal of Hospitality Management, 33, 6–18.

- Adhikari, A., & Bhattacharya, S. (2016). Appraisal of literature on customer experience in tourism sector: Review and framework. Current Issues in Tourism, 19(4), 296–321.

- Albayrak, T., Herstein, R., Caber, M., Drori, N., Bideci, M., & Berger, R. (2018). Exploring religious tourist experiences in Jerusalem: The intersection of Abrahamic religions. Tourism Management, 69, 285–296.

- Andersson, T. D. (2007). The tourist in the experience economy. Scandinavian Journal of Hospitality and Tourism, 7(1), 46–58.

- Arnould, E. J., & Price, L. L. (1993). River magic: Extraordinary experience and the extended service encounter. Journal of Consumer Research, 20(1), 24–45.

- Babin, B. J., Darden, W. R., & Griffin, M. (1994). Work and/or fun: Measuring hedonic and utilitarian shopping value. Journal of Consumer Research, 20(4), 644–656.

- Becker, L., & Jaakkola, E. (2020). Customer experience: Fundamental premises and implications for research. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 48(4), 630–648.

- Berry, L. L., Carbone, L. P., & Haeckel, S. H. (2002). Managing the total customer experience. MIT Sloan Management Review, 43(3), 85–89.

- Bharwani, S., & Jauhari, V. (2017). An exploratory study of competencies required to cocreate memorable customer experiences in the hospitality industry. In Hospitality marketing and consumer behavior (pp. 159–185). Apple Academic Press.

- Binkhorst, E., & Den Dekker, T. (2013). Agenda for co-creation tourism experience research. In Marketing of tourism experiences (pp. 219–235). Routledge.

- Boswijk, A., Thijssen, T., & Peelen, E. (2007). The experience economy: A new perspective. Pearson Education.

- Brakus, J. J., Schmitt, B. H., & Zarantonello, L. (2009). Brand experience: What is it? How is it measured? Does it affect loyalty? Journal of Marketing, 73(3), 52–68.

- Buhalis, D. (2000). Marketing the competitive destination of the future. Tourism Management, 21(1), 97–116.

- Carbone, L. P., & Haeckel, S. H. (1994). Engineering customer experiences. Marketing Management, 3(3), 8.

- Carù, A., & Cova, B. (2003). Revisiting consumption experience: A more humble but complete view of the concept. Marketing Theory, 3(2), 267–286.

- Cetin, G., Kizilirmak, I., Balik, M., & Kucukali, S. (2019). Impact of superior destination experience on recommendation. Trends in Tourist Behavior , 147–160.

- Cetin, G., & Walls, A. (2016). Understanding the customer experiences from the perspective of guests and hotel managers: Empirical findings from luxury hotels in Istanbul, Turkey. Journal of Hospitality Marketing & Management, 25(4), 395-424.

- Chen, J. S., Prebensen, N. K., & Uysal, M. (2014). Dynamic drivers of tourist experiences. In N.K.

- Chen, C.-C., Huang, W.-J., & Petrick, J. F. (2016). Holiday recovery experiences, tourism satisfaction and life satisfaction–Is there a relationship? Tourism Management, 53, 140–147.

- Cohen, E. 1979 A Phenomenology of Tourist Experiences. Sociology 13:179–201.

- Cohen, E. (1995). Contemporary tourism—Trends and challenges. In R. Butler and D. Pearce (Eds.), Change in tourism (pp. 12–29). London: Routledge

- Cova, B. (1996). What postmodernism means to marketing managers. European Management Journal, 14(5), 494–499.

- Cova, B., & Cova, V. (2009). Faces of the new consumer: A genesis of consumer governmentality. Recherche et Applications En Marketing (English Edition), 24(3), 81–99.

- Cracolici, M. F., & Nijkamp, P. (2009). The attractiveness and competitiveness of tourist destinations: A study of Southern Italian regions. Tourism Management, 30(3), 336–344.

- Crouch, G. I., & Ritchie, J. B. (2005). Application of the analytic hierarchy process to tourism choice and decision making: A review and illustration applied to destination competitiveness. Tourism Analysis, 10(1), 17– 25.

- Cutler, S. Q., & Carmichael, B. A. (2010). The dimensions of the tourist experience. In M. Morgan, P. Lugosi, & J. R. B. Ritchie (Eds.), The tourism and leisure experience. Consumer and managerial perspectives (pp. 3–26). Bristol, UK: Channel View Publications.

- Del Bosque, I. R., & San Martín, H. (2008). Tourist satisfaction a cognitive-affective model. Annals of Tourism Research, 35(2), 551–573.

- Featherstone, M. (1988). In pursuit of the postmodern: An introduction. Theory, Culture & Society, 5(2–3), 195–215.

- Firat, A. F., & Venkatesh, A. (1993). Postmodernity: The age of marketing. International Journal of Research in Marketing, 10(3), 227–249.

- Firat, A. F., & Venkatesh, A. (1995). Liberatory postmodernism and the reenchantment of consumption. Journal of Consumer Research, 22(3), 239–267.

- Fırat, A. F., & Dholakia, N. (2006). Theoretical and philosophical implications of postmodern debates: Some challenges to modern marketing. Marketing Theory, 6(2), 123–162.

- Firat, A. F. (1992). Postmodernism and the marketing organization. Journal of Organizational Change Management.

- Fick, G. R., & Brent Ritchie, J. R. (1991). Measuring service quality in the travel and tourism industry. Journal of Travel Research, 30(2), 2–9.

- Finsterwalder, J., & Kuppelwieser, V. G. (2011). Co-creation by engaging beyond oneself: The influence of task contribution on perceived customer-to-customer social interaction during a group service encounter. Journal of Strategic Marketing, 19(7), 607–618.

- Framke, W. (2002). The destination as a concept: A discussion of the business-related perspective versus the socio-cultural approach in tourism theory. Scandinavian Journal of Hospitality and Tourism, 2(2), 92–108.

- Gnoth, J., & Matteucci, X. (2014). A phenomenological view of the behavioural tourism research literature. International Journal of Culture, Tourism and Hospitality Research.

- Gretzel, U. & Jamal, T. (2009). Conceptualizing the Creative Tourist Class: Technology, Mobility, and Tourism Experiences. Tourism Analysis, 14(4): 471-481.

- Grewal, D., Levy, M., & Kumar, V. (2009). Customer experience management in retailing: An organizing framework. Journal of Retailing, 85(1), 1–14.

- Grönroos, C. (2001). The perceived service quality concept–a mistake? Managing Service Quality: An International Journal.

- Godovykh, M., & Tasci, A. D. (2020). Customer experience in tourism: A review of definitions, components, and measurements. Tourism Management Perspectives, 35, 100694.

- Gunn, C. A., & Taylor, G. D. (1973). Book Review: Vacationscape: Designing Tourist Regions: (Bureau of Business Research, The University of Texas at Austin, Austin, Texas, 1972, 238 pp., $8.00.). Journal of Travel Research, 11(3), 24–24.

- Heywood, J. L. (1987). Experience preferences of participants in different types of river recreation groups. Journal of Leisure Research, 19(1), 1–12.

- Hidalgo, M. C., & Hernandez, B. (2001). Place attachment: Conceptual and empirical questions. Journal of Environmental Psychology, 21(3), 273–281.

- Hirschman, E. C., & Holbrook, M. B. (1992). Postmodern consumer research (Vol. 1). Sage.

- Hirschman, E. C., & Holbrook, M. B. (1982). Hedonic consumption: Emerging concepts, methods and propositions. Journal of Marketing, 46(3), 92–101.

- Holbrook, M. B. (2000). The millennial consumer in the texts of our times: Experience and entertainment. Journal of Macromarketing, 20(2), 178–192.

- Holbrook, M. B. (2006a). Consumption experience, customer value, and subjective personal introspection: An illustrative photographic essay. Journal of Business Research, 59(6), 714–725.

- Holbrook, M. B., & Hirschman, E. C. (1982a). The experiential aspects of consumption: Consumer fantasies, feelings, and fun. Journal of Consumer Research, 9(2), 132–140.

- Hosany, S., & Gilbert, D. (2010). Measuring tourists’ emotional experiences toward hedonic holiday destinations. Journal of Travel Research, 49(4), 513–526.

- Hudson, S., & Ritchie, J. B. (2009). Branding a memorable destination experience. The case of Brand Canada.International Journal of Tourism Research, 11(2), 217–228.

- Huseynov, K., Costa Pinto, D., Maurer Herter, M., & Rita, P. (2020). Rethinking emotions and destination experience: An extended model of goal-directed behavior. Journal of Hospitality & Tourism Research, 44(7), 1153–1177. https://doi.org/10.1177/ 1096348020936334

- Hwang, J., & Seo, S. (2016). A critical review of research on customer experience management: Theoretical, methodological and cultural perspectives. International Journal of Contemporary Hospitality Management.

- Jaakkola, E., Helkkula, A., & Aarikka-Stenroos, L. (2015). Service experience co-creation: Conceptualization, implications, and future research directions. Journal of Service Management.

- Kandampully, J., Zhang, T. C., & Jaakkola, E. (2018a). Customer experience management in hospitality: A literature synthesis, new understanding and research agenda. International Journal of Contemporary Hospitality Management.

- Karayilan, E., & Cetin, G. (2016). Tourism destination: Design of experiences. The handbook of managing and marketing tourism experiences (pp. 65–83). Emerald Group Publishing Limited

- Kaushal, V. and Yadav, R. (2021), “Understanding customer experience of culinary tourism through food tours of Delhi”, International Journal of Tourism Cities , Vol. 7 No. 3, pp. 683 701. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJTC-08-2019-0135 Download as .RIS

- Ketter, E. (2018). It‗s all about you: Destination marketing campaigns in the experience economy era. Tourism Review.

- Kim, J.-H. (2014). The antecedents of memorable tourism experiences: The development of a scale to measure the destination attributes associated with memorable experiences. Tourism Management, 44, 34–45.

- Kim, J.-H., Ritchie, J. B., & McCormick, B. (2012). Development of a scale to measure memorable tourism experiences. Journal of Travel Research, 51(1), 12–25.

- King, J. (2002). Destination marketing organisations—Connecting the experience rather than promoting the place. Journal of Vacation Marketing, 8(2), 105–108.

- Kim, H., & So, K. K. F. (2022). Two decades of customer experience research in hospitality and tourism: A bibliometric analysis and thematic content analysis. International Journal of Hospitality Management, 100, 103082.

- Klaus and Maklan (2013), ―Towards a Better Measure of Customer Experience,‖ International Journal of Market Research, 55 (2), 227–46.

- Larsen, S. (2007). Aspects of a psychology of the tourist experience. Scandinavian Journal of Hospitality and Tourism, 7(1), 7–18.

- Lemon, K. N., & Verhoef, P. C. (2016). Understanding customer experience throughout the customer journey. Journal of Marketing, 80(6), 69–96.

- Lin, C.-H., & Kuo, B. Z.-L. (2016). The behavioral consequences of tourist experience. Tourism Management Perspectives, 18, 84–91.

- Lusch, R. F., & Vargo, S. L. (2006). Service-dominant logic: Reactions, reflections and refinements. Marketing Theory, 6(3), 281–288.

- Lugosi, P., & Walls, A. R. (2013). Researching destination experiences: Themes, perspectives and challenges. Journal of Destination Marketing and Management, 2(2), 51–58.

- Madrigal, R., & Kahle, L. R. (1994). Predicting vacation activity preferences on the basis of value-system segmentation. Journal of Travel Research, 32(3), 22–28.

- Mahmud, M.S. , Rahman, M.M. , Lima, R.P. and Annie, E.J. (2021), “Outbound medical tourism experience, satisfaction and loyalty: lesson from a developing country”, Journal of Hospitality and Tourism Insights , Vol. 4 No. 5, pp. 545-564. https://doi.org/10.1108/JHTI-06-2020-0094

- Maslow, A. H. (1964). Religions, values, and peak-experiences (Vol. 35). Ohio State University Press Columbus.

- Meyer, C., & Schwager, A. (2007). Customer experience. Harvard Business Review, 85(2), 116–126.

- Milman, A., Zehrer, A., & Tasci, A. D. (2017). Measuring the components of visitor experience on a mountain attraction: The case of the Nordkette, Tyrol, Austria. Tourism Review.

- Morgan, M., Elbe, J., & de Esteban Curiel, J. (2009a). Has the experience economy arrived? The views of destination managers in three visitor‐dependent areas. International Journal of Tourism Research, 11(2), 201– 216.

- Moscardo, G. (2009). Tourism and quality of life: Towards a more critical approach. Tourism and Hospitality Research, 9(2), 159–170.

- Mossberg, L. (2007). A marketing approach to the tourist experience. Scandinavian Journal of Hospitality and Tourism, 7(1), 59–74

- Murphy, L. (2001). Exploring social interactions of backpackers. Annals of Tourism Research, 28(1), 50–67.

- Neuhofer, B., Buhalis, D., & Ladkin, A. (2012). Conceptualising technology enhanced destination experiences. Journal of Destination Marketing & Management, 1(1–2), 36–46.

- Ofir, C., & Simonson, I. (2007). The effect of stating expectations on customer satisfaction and shopping experience. Journal of Marketing Research, 44(1), 164–174.

- Oh, H., Fiore, A. M., & Jeoung, M. (2007). Measuring Experience Economy Concepts: Tourism Applications. Journal of Travel Research , 46 (2), 119–132. https://doi.org/10.1177/0047287507304039

- Otto, J. E., & Ritchie, J. B. (1996). The service experience in tourism. Tourism Management, 17(3), 165–174.

- Oppermann, M. (2000). Tourism destination loyalty. Journal of Travel Research, 39(1), 78–84.

- Packer, J., & Ballantyne, R. (2016). Conceptualizing the visitor experience: A review of literature and development of a multifaceted model. Visitor Studies, 19(2), 128–143.

- Palmer, A. (2010). Customer experience management: A critical review of an emerging idea. Journal of Services Marketing.

- Park, S., & Santos, C. A. (2017). Exploring the tourist experience: A sequential approach. Journal of Travel Research, 56(1), 16–27.

- Pearce, P. L., & Caltabiano, M. L. (1983). Inferring travel motivation from travelers’ experiences. Journal of Travel Research, 22(2), 16–20.

- Pine, B. J., Pine, J., & Gilmore, J. H. (1999). The experience economy: Work is theatre & every business a stage. Harvard Business Press.

- Prahalad, C. K., & Ramaswamy, V. (2004). Co-creation experiences: The next practice in value Journal of Interactive Marketing, 18(3), 5–14.

- Prayag, G., Hosany, S., Muskat, B., & Del Chiappa, G. (2017). Understanding the relationships between tourists’ emotional experiences, perceived overall image, satisfaction, and intention to recommend. Journal of Travel Research, 56(1), 41–54.

- Prebensen, N. K., Woo, E., Chen, J. S., & Uysal, M. (2013). Motivation and involvement as antecedents of the perceived value of the destination experience. Journal of Travel Research, 52(2), 253–264.

- Prentice, R. C., Witt, S. F., & Hamer, C. (1998). Tourism as experience: The case of heritage parks. Annals of Tourism Research, 25(1), 1–24.

- Quan, S., & Wang, N. (2004). Towards a structural model of the tourist experience: An illustration from food experiences in tourism. Tourism Management, 25(3), 297–305.

- Räikkönen, J., & Honkanen, A. (2013). Does satisfaction with package tours lead to successful vacation experiences? Journal of Destination Marketing & Management, 2(2), 108–117.

- Rather, R.A. (2020), “Customer experience and engagement in tourism destinations: the experiential marketing perspective”, Journal of Travel and Tourism Marketing, Vol. 37 No. 1, pp. 15-32

- Richards, G., & Wilson, J. (2006). Developing creativity in tourist experiences: A solution to the serial reproduction of culture? Tourism Management, 27(6), 1209–1223 doi:10.1016/j.tourman.2005.06. 002.

- Saraniemi, S., & Kylänen, M. (2011). Problematizing the concept of tourism destination: An analysis of different theoretical approaches. Journal of Travel Research, 50(2), 133–143.

- Schmitt, B. (1999). Experiential marketing. Journal of Marketing Management, 15(1–3), 53–67.

- Schmitt, B. H. (2010). Customer experience management: A revolutionary approach to connecting with your customers. John Wiley & Sons.

- Scott, N., Laws, E., & Boksberger, P. (2009). The marketing of hospitality and leisure experiences. Journal of Hospitality Marketing & Management, 18(2–3), 99–110.

- Shafiee, M. M., Foroudi, P., & Tabaeeian, R. A. (2021). Memorable experience, tourist-destination identification and destination love. International Journal of Tourism Cities. Article in press. http://dx.doi.org/10.1108/IJTC-09-2020-0176

- Sugathan, P., & Ranjan, K. R. (2019). Co-creating the tourism experience. Journal of Business Research, 100(Jul), 207–217

- Suvantola, J. 2002 Tourist‗s Experience of Place. Burlington: Ashgate

- Tarssanen, S., and M. Kylänen (2006). “A Theoretical Model for Producing Experiences—A Touristic Perspective.” In Articles on Experiences 2, 2nd edition, edited by M. Kylänen.Rovaniemi, Finland: Lapland Centre of Expertise for the Experience Industry, pp. 134-54

- Tung, V. W. S., & Ritchie, J. B. (2011a). Exploring the essence of memorable tourism experiences. Annals of Tourism Research, 38(4), 1367–1386.

- Turner, B. S., & Turner, B. S. T. (1990). Theories of modernity and postmodernity.

- Tynan, C., & McKechnie, S. (2009). Hedonic meaning creation though Christmas consumption: A review and model. Journal of Customer Behaviour, 8(3), 237–255.

- Uriely, N. (2005). The tourist experience: Conceptual developments. Annals of Tourism Research, 32(1), 199– 216.

- Unger, L. S., & Kernan, J. B. (1983). On the meaning of leisure: An investigation of some determinants of the subjective experience. Journal of Consumer Research, 9(4), 381–392.

- Vargo, S. L., & Lusch, R. F. (2004). Evolving to a new dominant logic for marketing. Journal of Marketing, 68(1), 1–17.

- Verhulst, N., De Keyser, A., Gustafsson, A., Shams, P., & Van Vaerenbergh, Y. (2019). Neuroscience in service research: An overview and discussion of its possibilities. Journal of Service Management.

- Verhulst, N., Vermeir, I., Slabbinck, H., Lariviere, B., Mauri, M., & Russo, V. (2020). A neurophysiological exploration of the dynamic nature of emotions during the customer experience. Journal of Retailing and Consumer Services, 57, 102217.

- Verleye, K. (2015). The co-creation experience from the customer perspective: Its measurement and determinants. Journal of Service Management.

- Vittersø, J., Vorkinn, M., Vistad, O. I., & Vaagland, J. (2000). Tourist experiences and attractions. Annals of Tourism Research, 27(2), 432–450

- Volo, S. (2009). Conceptualizing experience: A tourist based approach. Journal of Hospitality Marketing & Management, 18(2–3), 111–126.

- Walls, A. R., Okumus, F., Wang, Y. R., & Kwun, D. J.-W. (2011). An epistemological view of consumer experiences. International Journal of Hospitality Management, 30(1), 10–21.

- Wijaya, B. S. (2013). Dimensions of brand image: A conceptual review from the perspective of brand communication. European Journal of Business and Managemrnt, 5(31), 55–65.

- Wu, T. C., Xie, P. F., & Tsai, M. C. (2015). Perceptions of attractiveness for salt heritage tourism: A tourist perspective. Tourism Management, 51, 201–209

Conferences

Latest articles, latest coip articles, +general information, publication ethics, indexing and abstracting, international editorial board, open access, lifetime article preservation.

ORIGINAL RESEARCH article

Tourism experience and construction of personalized smart tourism program under tourist psychology.

- 1 Faculty of International Tourism and Management, City University of Macau, Macao, China

- 2 Faculty of Law, Hebei University, Baoding, China

- 3 School of Public Economics and Administration, Shanghai University of Finance and Economics, Shanghai, China

- 4 School of Business, Macau University of Science and Technology, Macao, China

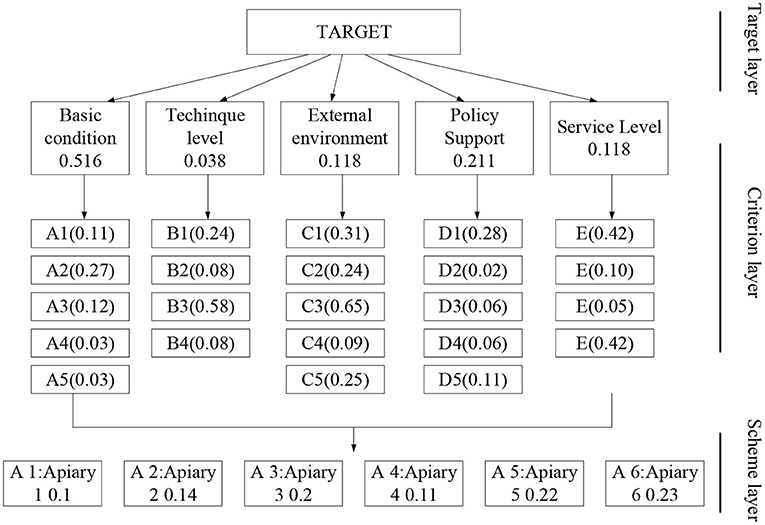

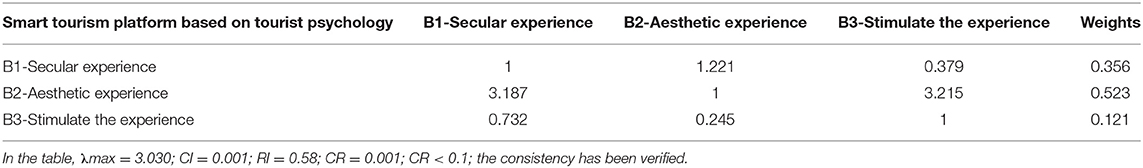

- 5 Department of Environmental Art and Design, China Academy of Art, Hangzhou, China

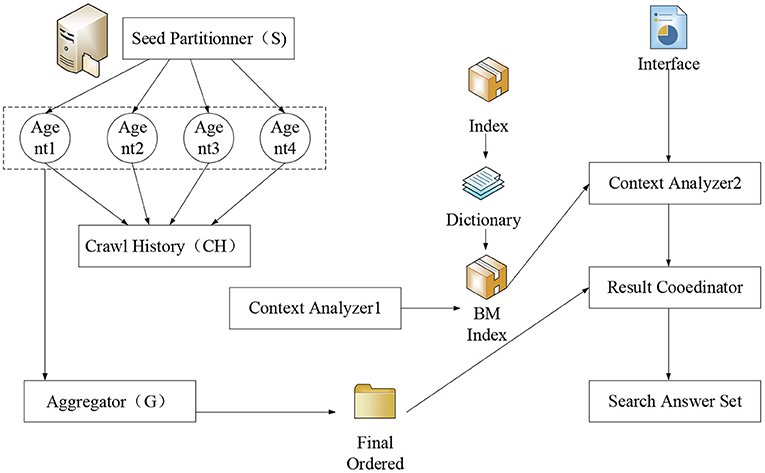

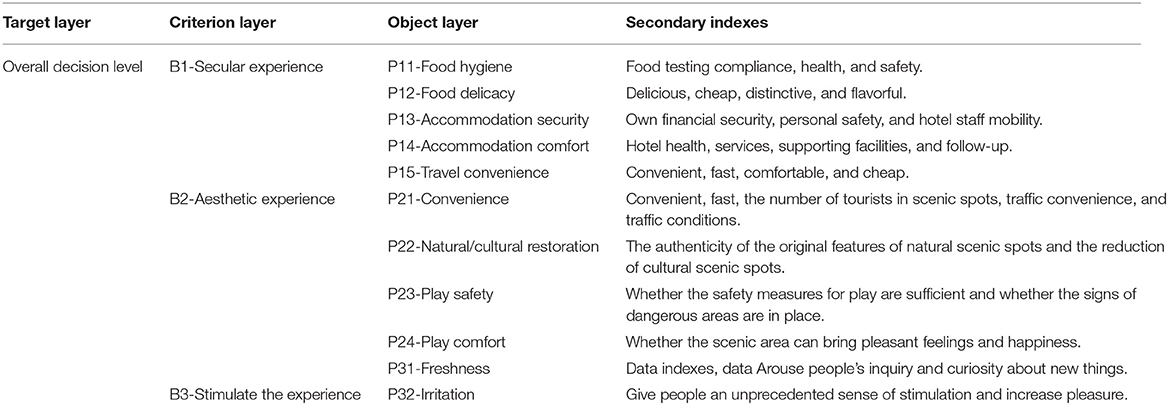

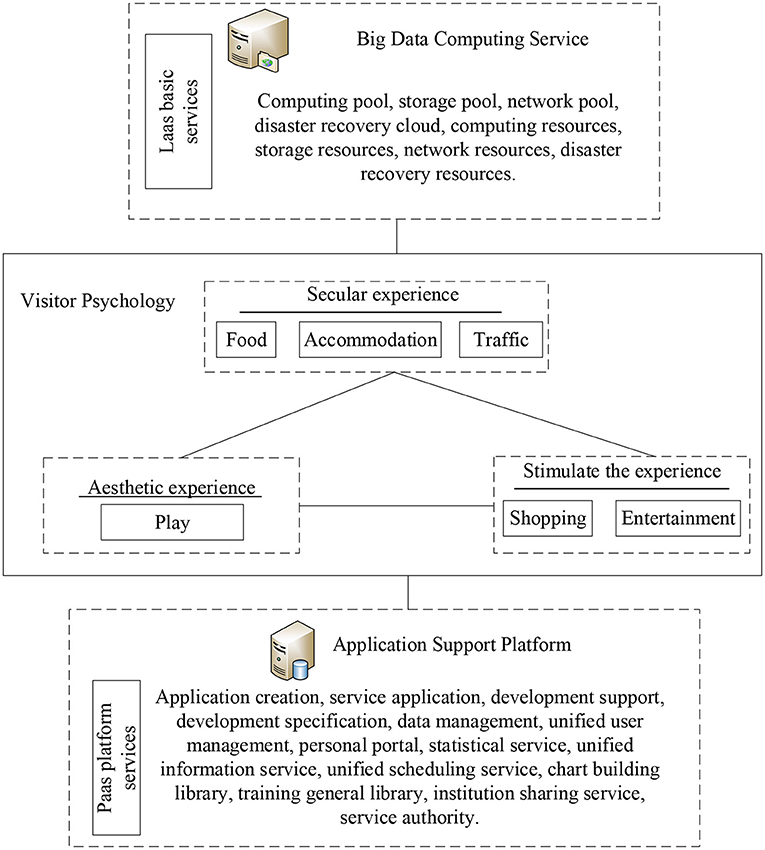

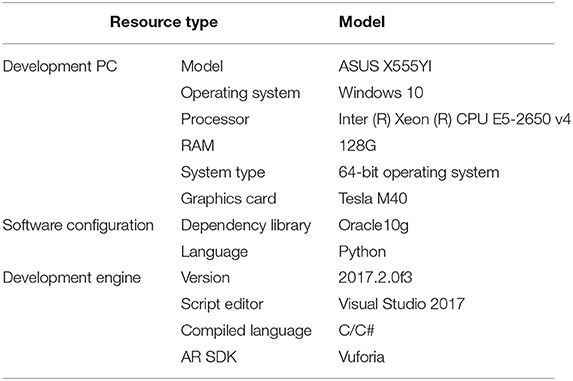

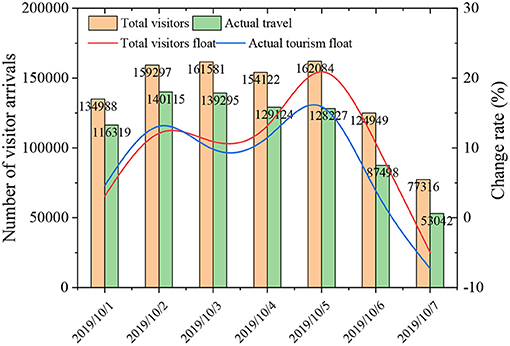

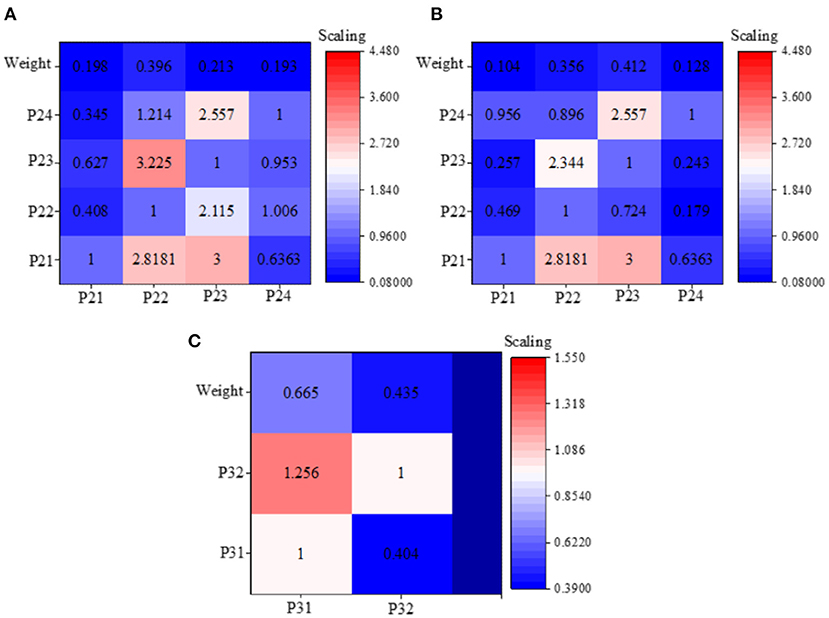

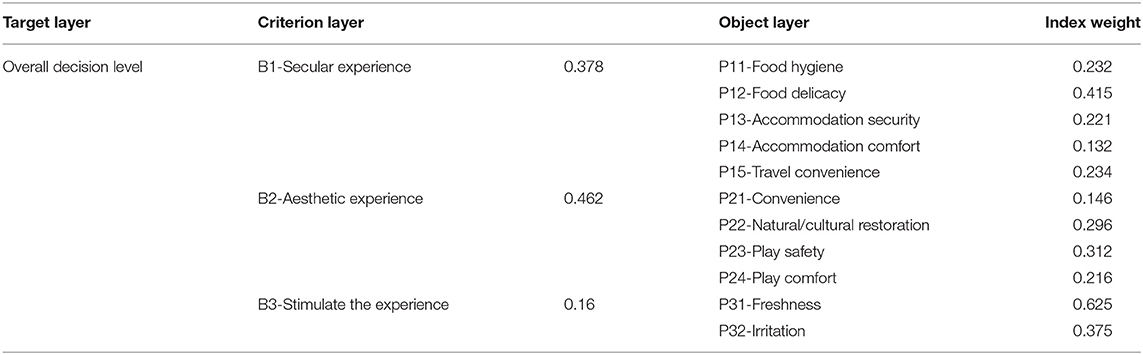

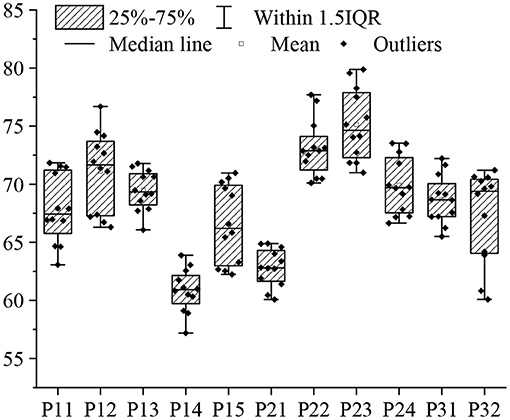

The present work aims to boost tourism development in China, grasp the psychology of tourists at any time, and provide personalized tourist services. The research object is the tourism industry in Macau. In particular, tourists' experiences are comprehensively analyzed in terms of dining, living, traveling, sightseeing, shopping, and entertaining as per their psychological changes using approaches including big data analysis, literature analysis, and field investigation. In this case, a model of tourism experience formation path is summarized, and a smart travel solution is proposed based on psychological experience. In the end, specific and feasible suggestions are put forward for the Macau tourism industry. Results demonstrate that the psychology-based smart travel solution exerts a significant impact on tourists' tourism experience. Specifically, the weight of secular tourism experience is 0.523, the weight of aesthetic tourism experience is 0.356, and the weight of stimulating tourism experience is 0.121. Tourists prefer travel destinations with excellent urban security and scenic authenticity. They give the two indexes comprehensive scores of 75.14 points and 73.12 points, respectively. The proposed smart travel solution can grasp the psychology of tourists and enhance their tourism experiences. It has strong practical and guiding significances, which can promote constructing smart travel services in Macau and enhancing tourism experiences.

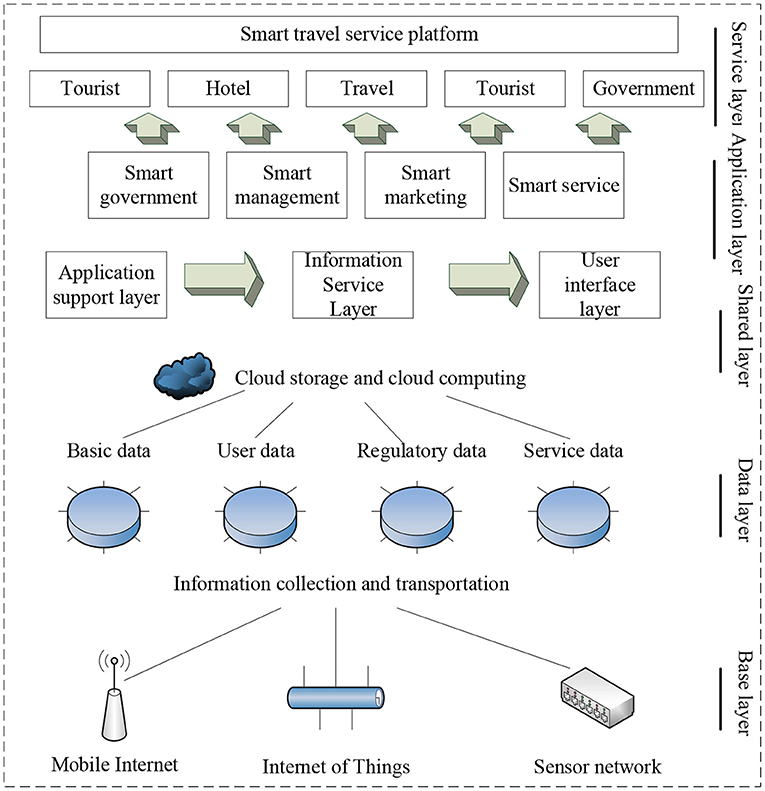

While China's national strength is improving continuously, people's requirements for the quality of life also becomes higher, and tourism expenditure has increased its share of all living consumption expenditures ( Sun et al., 2020 ). Tourism is an important indicator to measure the happiness and life satisfaction of people; it also reflects the level of living standards. In China, the central government proposed a strategic plan for the development of smart tourism in 2011 ( Watson et al., 2017 ). Supported by the national tourism policy, many smart tourism cities have emerged one after another. The key to smart tourism is to integrate tourism data, including traffic, weather, management, passenger flow, and other data that need to be integrated and considered ( Gretzel et al., 2015 ). Before tourists leave for their destinations, various types of consultation, navigation, and information-sharing services are very critical. As the internet advances, applying new information technology to the tourism industry has become a general trend; as a result, data of the tourism industry has become a hot issue ( Alaei et al., 2019 ). Big data technology is developed on the basis of information technologies, including the internet and cloud computing. This technology plays a vital role in developing tourism products, improving tourism services, and tourism marketing ( Lv et al., 2019 ). A smart tourism service platform is built according to the data of the tourism industry to provide tourists with diversified services and make the tourism experience more personalized and authentic. This model is of great significance for promoting the transformation, upgrading, and sustainable development of the tourism industry.

The smart tourism is centered on the personalization of tourists. Supported by the new generation of communication and internet technologies, smart tourism increases interactive experience, gathers tourism information, and promotes the upgrading and transformation of the tourism industry ( Skavronskaya et al., 2020a ). The research on psychology-based tourism experience focuses on the travel psychology and preferences of tourists. Analyzing several reports on tourism psychology, Cicerali et al. (2017) found that the most critical factors that harmed tourism satisfaction among tourism environmental factors were sanitary conditions, social influence, scenic area design, and tourism atmosphere. Studying the negative psychology of tourists, Nawijn and Biran (2019) discovered that different types of negative emotions would affect the lives of consumers, while traveling could promote the emotional experiences and improve the negative emotions. Skavronskaya et al. (2020b) proposed a conceptual model called “cognitive evaluation of novelty in unforgettable tourism experience.” They believed that future works should consider applying this model to advance the tourism experience and analyze such experience as a psychological phenomenon. However, the existing methods cannot solve the problems hindering the sustainable development of tourism fundamentally. Therefore, constructing a smart tourism platform based on tourists' psychology is a critical and urgent issue in the tourism industry.

Therefore, influencing factors of the smart tourism industry are analyzed to clarify the specific evaluation indexes. Besides, three tourism experiences, namely secular tourism experience, aesthetic tourism experience, and stimulating tourism experience, are analyzed from six perspectives: dining, living, traveling, sightseeing, shopping, and entertaining. At last, a personalized smart tourism platform founded on tourism psychology is proposed. Through simulation experiments, the platform's effectiveness is validated; on this basis, countermeasures and suggestions are put forward for constructing the smart tourism of Macau. To sum up, a smart tourism platform is built using data mining technology, which can promote the smart tourism development in Macau and provide a basis for the sustainable development of Macau's tourism industry.

Literature Review

Related works of smart travel.

Smart travel uses new technologies such as cloud computing and the Internet of Things (IoT) to actively perceive information about tourism resources, tourism economy, tourism activities, and tourists through the internet or mobile internet using portable terminal internet devices. It then timely releases the perceived information, allowing people to access the information they need in time to arrange their schedules. Eventually, intelligent perception and convenient use of all kinds of travel information can be achieved ( Kharisma and Muni, 2017 ). Smart travel can be reflected in tourism management, tourism services, and tourism marketing. When people propose the concept of smart travel, they put forward various thoughts on smart travel as per different research directions ( Cui and Long, 2019 ). Li et al. (2017) believed that smart travel was a unique creative tourism. Liberato et al. (2018) thought that smart travel was first a change in the concept of development. Buhalis (2019) pointed out that smart travel was an integration of the new generation of information and communication technologies. Femenia-Serra and Neuhofer (2018) researched the development momentum of smart travel regarding its driving factors. Thakuriah et al. (2020) introduced the relationship between smart city and smart travel and expounded the role of smart travel from multiple angles. Shafiee et al. (2019) introduced the history, framework, value, and development trend of smart travel. Gretzel and de Mendonça (2019 ) explained the deficiencies of smart travel. Sun et al. (2019) researched smart travel according to the current situation and problems, development countermeasures, and development prospects. Gretzel and Koo (2021) proposed to build and manage a “smart travel public service platform.” Smart travel is a significant innovation in the tourism industry. Its innovation path is formed based on the efficient flow and effective integration of tourism information in the tourism industry. The innovative means include the internet, big data, cloud computing, and other new-generation information technologies, as well as business model innovation. Ultimately, the purpose of innovation is to improve tourism services and tourists' satisfaction.

Development and Application of Big Data

Big data refers to a collection of data whose content cannot be captured, managed, and processed with conventional software tools within a time frame. Big data technology can quickly obtain valuable information from various types of data. Technologies applicable to big data include massively parallel processing databases, data mining grids, distributed file systems, distributed databases, cloud computing platforms, the internet, and scalable storage systems ( Le et al., 2019 ). Lately, new technologies such as IoT, artificial intelligence, and cloud computing have been accepted in various fields. Chen et al. (2019) believed that these new things were inseparable from the support of big data. A large number of research results have also emerged in the process of assisting in the transformation and upgrading of various industries ( Chen et al., 2019 ). Zhu et al. (2019) proved that combining big data and cloud computing could give new value to the data held by operators. Liu et al. (2020) suggested that big data could bring new ideas to the operation and management of the hotel industry. Du et al. (2020) believed that big data would contribute to tourism management and the development of global tourism. As mobile internet and big data develop rapidly, research on smart travel has gone beyond the theoretical level; scholars begin to combine smart travel with big data and cloud computing to explore a way to practice smart travel ( Du et al., 2020 ). Joubert et al. (2021) studied the operation mode of smart travel by combining value chain management, supply chain management, and other operation management theories. Gao (2021) improved the practicability of smart travel by studying the technical implementation methods behind smart travel. They also explored the combination of smart travel and rural tourism from different angles.

Related Works of Tourism Psychology

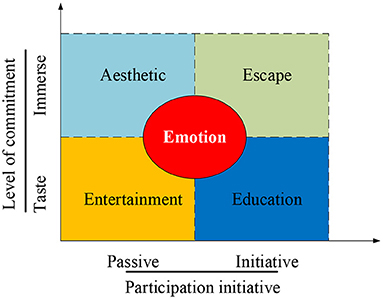

People participating in tourism activities include actual tourists, potential tourists, and various practitioners of the tourism industry. They have different psychological activities in tourism activities and therefore behave differently ( Skavronskaya et al., 2020c ). There are always contacts and connections among tourists, “tourism products,” tourism service personnel, and tourism enterprise management personnel in tourism activities. These mutual contacts and interpersonal relationships depend on people's psychological activities. Tourism psychology studies the laws of these people's psychological activities and behaviors in tourism activities. Psychological activities and behaviors are inseparable. Psychology governs behavior, and behavior reflects psychology ( Kesenheimer and Greitemeyer, 2021 ). Tourism experience is a comprehensive experience based on super-utilitarian experience. While enjoying this experience, tourists can obtain aesthetic pleasure by observing the scenery, appreciate a colorful life in the interaction with others, discover and develop themselves in the process of actively imitating other roles, and also relish secular pleasures through tourism consumption.

A Review of Related Works