Take advantage of the search to browse through the World Heritage Centre information.

Sustainable Tourism

UNESCO World Heritage and Sustainable Tourism Programme

The UNESCO World Heritage and Sustainable Tourism Programme represents a new approach based on dialogue and stakeholder cooperation where planning for tourism and heritage management is integrated at a destination level, the natural and cultural assets are valued and protected, and appropriate tourism developed.

World Heritage and tourism stakeholders share responsibility for conservation of our common cultural and natural heritage of Outstanding Universal Value and for sustainable development through appropriate tourism management.

Facilitate the management and development of sustainable tourism at World Heritage properties through fostering increased awareness, capacity and balanced participation of all stakeholders in order to protect the properties and their Outstanding Universal Value.

Focus Areas

Policy & Strategy

Sustainable tourism policy and strategy development.

Tools & Guidance

Sustainable tourism tools

Capacity Building

Capacity building activities.

Heritage Journeys

Creation of thematic routes to foster heritage based sustainable tourism development

A key goal of the UNESCO WH+ST Programme is to strengthen the enabling environment by advocating policies and frameworks that support sustainable tourism as an important vehicle for managing cultural and natural heritage. Developing strategies through broad stakeholder engagement for the planning, development and management of sustainable tourism that follows a destination approach and focuses on empowering local communities is central to UNESCO’s approach.

Supporting Sustainable Tourism Recovery

Enhancing capacity and resilience in 10 World Heritage communities

Supported by BMZ, and implemented by UNESCO in collaboration with GIZ, this 2 million euro tourism recovery project worked to enhance capacity building in local communities, improve resilience and safeguard heritage.

Policy orientations

Defining the relationship between world heritage and sustainable tourism

Based on the report of the international workshop on Advancing Sustainable Tourism at Natural and Cultural Heritage Sites (Mogao, China, September 2009), the World Heritage Committee at its 34th session adopted the policy orientations which define the relationship between World Heritage and sustainable tourism ( Decision 34 COM 5F.2 ).

World Heritage and Tourism in a Changing Climate

Providing an overview of the increasing vulnerability of World Heritage sites to climate change impacts and the potential implications for and of global tourism.

Sustainable Tourism Tools

Manage tourism efficiently, responsibly and sustainably based on the local context and needs

People Protecting Places is the public exchange platform for the World Heritage and Sustainable Tourism Programme, providing education and information, encouraging support, engaging in social and community dialogue

The ' How-To ' guides offer direction and guidance to managers of World Heritage tourism destinations and other stakeholders to help identify the most suitable solutions for circumstances in their local environments and aid in developing general know-how.

English French Russian

Helping site managers and other tourism stakeholders to manage tourism more sustainably

Capacity Building in 4 Africa Nature Sites

A series of practical training and workshops were organized in four priority natural World Heritage sites in Africa (Lesotho, Malawi, South Africa, Tanzania, Zambia and Zimbabwe) with the aim of providing capacity building tools and strategies for site managers to help them manage tourism at their sites more sustainably.

Learn more →

15 Pilot Sites in Nordic-Baltic Region

The project Towards a Nordic-Baltic pilot region for World Heritage and Sustainable Tourism (2012-2014) was initiated by the Nordic World Heritage Foundation (NWHF). With a practical approach, the project has contributed to tools for assessing and developing sustainable World Heritage tourism strategies with stakeholder involvement and cooperation.

Supporting Community-Based Management and Sustainable Tourism at World Heritage sites in South-East Asia

Entitled “The Power of Culture: Supporting Community-Based Management and Sustainable Tourism at World Heritage sites in South-East Asia", the UNESCO Office in Jakarta with the technical assistance of the UNESCO World Heritage and Sustainable Tourism Programme and the support from the Government of Malaysia is spearheading the first regional effort in Southeast Asia to introduce a new approach to sustainable tourism management at World Heritage sites in Malaysia, the Philippines and Indonesia.

Cultural tourism is one of the largest and fastest-growing global tourism markets. Culture and creative industries are increasingly being used to promote destinations and enhance their competitiveness and attractiveness.

Many locations are now actively developing their cultural assets as a means of developing comparative advantages in an increasingly competitive tourism marketplace, and to create local distinctiveness in the face of globalization.

UNESCO will endeavour to create networks of key stakeholders to coordinate the destination management and marketing associated with the different heritage routes to promote and coordinate high-quality, unique experiences based on UNESCO recognized heritage. The goal is to promote sustainable development based on heritage values and create added tourist value for the sites.

UNESCO World Heritage Journeys of the EU

Creating heritage-based tourism that spurs investment in culture and the creative industries that are community-centered and offer sustainable and high-quality products that play on Europe's comparative advantages and diversity of its cultural assets.

World Heritage Journeys of Buddhist Heritage Sites

UNESCO is currently implementing a project to develop a unique Buddhist Heritage Route for Sustainable Tourism Development in South Asia with the support from the Korea International Cooperation Agency (KOICA). South Asia is host to rich Buddhist heritage that is exemplified in the World Heritage properties across the region.

Programme Background

In 2011 UNESCO embarked on developing a new World Heritage and Sustainable Tourism Programme.

The aim was to create an international framework for the cooperative and coordinated achievement of shared and sustainable outcomes related to tourism at World Heritage properties.

The preparatory work undertaken in developing the Programme responded to the decision 34 COM 5F.2 of the World Heritage Committee at its 34th session in Brasilia in 2010, which requested

“the World Heritage Centre to convene a new and inclusive programme on World Heritage and Sustainable Tourism, with a steering group comprising interested States Parties and other relevant stakeholders, and also requests the World Heritage Centre to outline the objectives and approach to the implementation of this programme".

The Steering Group was comprised of States Parties representatives from the six UNESCO Electoral Groups (Germany (I), Slovenia (II), Argentina (III), China (IV), Tanzania (Va), and Lebanon (Vb)), the Director of the World Heritage Centre, the Advisory Bodies (IUCN, ICOMOS and ICCROM), the United Nations World Tourism Organization (UNWTO) and the Swiss Government as the donor agency.

The Government of Switzerland has provided financial support for specific actions to be undertaken by the Steering Group. To coordinate and support the process, the World Heritage Centre has formed a small Working Group with the support of the Nordic World Heritage Foundation, the Government of Switzerland and the mandated external consulting firm MartinJenkins.

The World Heritage Committee directed that the Programme take into account:

- the recommendations of the evaluation of the concluded tourism programme ( WHC-10/34.COM/INF.5F.3 )

- the policy orientation which defines the relationship between World Heritage and sustainable tourism that emerged from the workshop Advancing Sustainable Tourism at Natural and Cultural Heritage Sites (Mogao, China, September 2009) ( WHC-10/34.COM/INF.5F.1 )

Overarching and strategic processes that the new World Heritage and Sustainable Tourism Programme will be aligned with include the Strategic Objectives of the World Heritage Convention (the five C's) ( Budapest Declaration 2002 ), the ongoing Reflections on the Future of the World Heritage Convention ( WHC-11/35.COM/12A ) and the Strategic Action Plan for the Implementation of the World Heritage Convention 2012-2022 ( WHC-11/18.GA/11 ), the Relationship between the World Heritage Convention and Sustainable Development (WHC-10/34.COM/5D), the World Heritage Capacity Building Strategy ( WHC-10/34.COM/5D ), the Global Strategy for a Representative, Balanced and Credible World Heritage List (1994), and the Evaluation of the Global Strategy and PACT initiative ( WHC-11/18.GA/8 - 2011 ).

In addition, the programme development process has been enriched by an outreach to representatives from the main stakeholder groups including the tourism sector, national and local governments, site practitioners and local communities. The programme design was further developed at an Expert Meeting in Sils/Engadine, Switzerland October 2011. In this meeting over 40 experts from 23 countries, representing the relevant stakeholder groups, worked together to identify the overall strategic approach and a prioritised set of key objectives and activities. The proposed Programme was adopted by the World Heritage Committee in 2012 at its 36th session in St Petersburg, Russian Federation .

International Instruments

International Instruments Relating to Sustainable Development and Tourism.

Resolutions adopted by the United Nations, charters adopted by ICOMOS, decisions adopted by the World Heritage Committee, legal instruments adopted by UNESCO on heritage preservation.

Resolutions adopted by the United Nations

- Report by the Department of Economics and Social Affairs: Tourism and Sustainable Development: The Global Importance of Tourism at the United Nations’ Commission on Sustainable Development 7th Session (1999)

- Resolution A/RES/56/212 and the Global Code of Ethics for Tourism adopted by the United Nations World Tourism Organization (1999)

Charters adopted by ICOMOS

- The ICOMOS International Cultural Tourism Charter (1999)

- The ICOMOS Charter for the Interpretation and Presentation of Cultural Heritage Sites (2008)

Decisions adopted by the World Heritage Committee

- Decision (XVII.4-XVII.12) adopted by the World Heritage Committee at its 25th Session in Helsinki (2001)

- Decision 33 COM 5A adopted by the World Heritage Committee at its 30th Session in Seville (2009)

- Decision 34 COM 5F.2 adopted by the World Heritage Committee at its 34th Session in Brasilia (2010)

- Decision 36 COM 5E adopted by the World Heritage Committee at its 36th Session in Saint Petersburg (2012)

Legal instruments adopted by UNESCO on heritage preservation in chronological order

- Convention on the Means of Prohibiting and Preventing the Illicit Import, Export and Transfer of Ownership of Cultural Property (1970)

- The Recommendation for the Protection of Movable Cultural Property (1978)

- The Recommendation on the Safeguarding of Traditional Culture and Folklore (1989)

- The Convention on the Protection of the Underwater Cultural heritage (2001)

- The Convention on the Protection and Promotion of the Diversity of Cultural Expressions (2005)

Other instruments

- Other instruments OECD Tourism Trends and Policies 2012 (French forthcoming)

- Programme on Sustainable Consumption and Production (In English)

- Siem Reap Declaration on Tourism and Culture 2015 – Building a New Partnership Model

Decisions / Resolutions (5)

The World Heritage Committee,

- Having examined Document WHC/18/42.COM/5A,

- Recalling Decision 41 COM 5A adopted at its 41st session (Krakow, 2017) and Decision 40 COM 5D adopted at its 40th session (Istanbul/UNESCO, 2016), General:

- Takes note with appreciation of the activities undertaken by the World Heritage Centre over the past year in pursuit of the Expected Result to ensure that “tangible heritage is identified, protected, monitored and sustainably managed by Member States, in particular through the effective implementation of the 1972 Convention ”, and the five strategic objectives as presented in Document WHC/18/42.COM/5A;

- Welcomes the proactive role of the Secretariat for enhancing synergies between the World Heritage Convention and the other Culture and Biodiversity-related Conventions, particularly the integration of relevant synergies aspects in the revised Periodic Reporting Format and the launch of a synergy-related web page on the Centre’s website;

- Also welcomes the increased collaboration among the Biodiversity-related Conventions through the Biodiversity Liaison Group and focused activities, including workshops, joint statements and awareness-raising;

- Takes note of the Thematic studies on the recognition of associative values using World Heritage criterion (vi) and on interpretation of sites of memory, funded respectively by Germany and the Republic of Korea and encourages all States Parties to take on board their findings and recommendations, in the framework of the identification of sites, as well as management and interpretation of World Heritage properties;

- Noting the discussion paper by ICOMOS on Evaluations of World Heritage Nominations related to Sites Associated with Memories of Recent Conflicts, decides to convene an Expert Meeting on sites associated with memories of recent conflicts to allow for both philosophical and practical reflections on the nature of memorialization, the value of evolving memories, the inter-relationship between material and immaterial attributes in relation to memory, and the issue of stakeholder consultation; and to develop guidance on whether and how these sites might relate to the purpose and scope of the World Heritage Convention , provided that extra-budgetary funding is available and invites the States Parties to contribute financially to this end;

- Also invites the States Parties to support the activities carried out by the World Heritage Centre for the implementation of the Convention ;

- Requests the World Heritage Centre to present, at its 43rd session, a report on its activities. Thematic Programmes:

- Welcomes the progress report on the implementation of the World Heritage Thematic Programmes and Initiatives, notes their important contribution towards implementation of the Global Strategy for representative World Heritage List, and thanks all States Parties, donors and other organizations for having contributed to achieving their objectives;

- Acknowledges the results achieved by the World Heritage Cities Programme and calls States Parties and other stakeholders to provide human and financial resources ensuring the continuation of this Programme in view of its crucial importance for the conservation of the urban heritage inscribed on the World Heritage List, for the implementation of the Recommendation on the Historic Urban Landscape and its contribution to achieving the 2030 Sustainable Development Goals related to cities as well as for its contribution to the preparation of the New Urban Agenda, and further thanks to China and Croatia for their support for the implementation of the Programme;

- Also acknowledges the results achieved of the World Heritage Marine Programme, also thanks Flanders, France and the Annenberg Foundation for their support, notes the increased focus of the Programme on a global managers network, climate change adaptation strategies and sustainable fisheries, and invites States Parties, the World Heritage Centre and other stakeholders to continue to provide human and financial resources to support for the implementation of the Programme;

- Further acknowledges the results achieved in the implementation of the World Heritage Sustainable Tourism Programme, in particular the development of the Sustainable Tourism and Visitor Management Assessment tool and encourages States Parties to participate in the pilot testing of the tool, expresses appreciation for the funding provided by the European Commission and further thanks the Republic of Korea, Norway, and Seabourn Cruise Line for their support in the implementation of the Programme’’s activities;

- Further notes the progress in the implementation of the Small Island Developing States Programme, its importance for a representative, credible and balanced World Heritage List and building capacity of site managers and stakeholders to implement the World Heritage Convention , thanks furthermore Japan and the Netherlands for their support as well as the International Centre on Space Technology for Natural and Cultural Heritage (HIST) and the World Heritage Institute of Training & Research for the Asia & the Pacific Region (WHITRAP) as Category 2 Centres for their technical and financial supports and also requests the States Parties and other stakeholders to continue to provide human, financial and technical resources for the implementation of the Programme;

- Takes note of the activities implemented jointly by the International Astronomical Union (IAU) and ICOMOS under the institutional guidance of the World Heritage Centre, in line with its Decision 40 COM 5D, further requests the World Heritage Centre to disseminate among the States Parties the second volume of the IAU/ICOMOS Thematic Study on Astronomical Heritage and renames this initiative as Initiative on Heritage of Astronomy, Science and Technology;

- Also takes note of the progress report on the Initiative on Heritage of Religious Interest, endorses the recommendations of the Thematic Expert Consultation meetings focused on Mediterranean and South-Eastern Europe (UNESCO, 2016), Asia-Pacific (Thailand, 2017) and Eastern Europe (Armenia, 2018), thanks the States Parties for their generous contribution and reiterates its invitation to States Parties and other stakeholders to continue to support this Initiative, as well as its associated Marketplace projects developed by the World Heritage Centre;

- Takes note of the activities implemented by CRATerre in the framework of the World Heritage Earthen Architecture Programme, under the overall institutional guidance of the World Heritage Centre, and of the lines of action proposed for the future, if funding is available;

- Invites States Parties, international organizations and donors to contribute financially to the Thematic Programmes and Initiatives as the implementation of thematic priorities is no longer feasible without extra-budgetary funding;

- Requests furthermore the World Heritage Centre to submit an updated result-based report on Thematic Programmes and Initiatives, under Item 5A: Report of the World Heritage Centre on its activities, for examination by the World Heritage Committee at its 44th session in 2020.

1. Having examined document WHC-12/36.COM/5E,

2. Recalling Decision 34 COM 5F.2 adopted at its 34th session (Brasilia, 2010),

3. Welcomes the finalization of the new and inclusive Programme on World Heritage and Sustainable Tourism and notes with appreciation the participatory process for its development, objectives and approach towards implementation;

4. Also welcomes the contribution of the Steering Group comprised of States Parties representatives from the UNESCO Electoral Groups, the World Heritage Centre, the Advisory Bodies (IUCN, ICOMOS, ICCROM), Switzerland and the United Nations World Tourism Organisation (UNWTO) in the elaboration of the Programme;

5. Thanks the Government of Switzerland, the United Nations Foundation and the Nordic World Heritage Foundation for their technical and financial support to the elaboration of the Programme;

6. Notes with appreciation the contribution provided by the States Parties and other consulted stakeholders during the consultation phase of the Programme;

7. Takes note of the results of the Expert Meeting in Sils/Engadin (Switzerland), from 18 to 22 October 2011 contributing to the Programme, and further thanks the Government of Switzerland for hosting the Expert Meeting;

8. Adopts the World Heritage and Sustainable Tourism Programme;

9. Requests the World Heritage Centre to refine the Draft Action Plan 2013-2015 in an Annex to the present document and to implement the Programme with a Steering Group comprised of representatives of the UNESCO Electoral Groups, donor agencies, the Advisory Bodies, UNWTO and in collaboration with interested stakeholders;

10. Notes that financial resources for the coordination and implementation of the Programme do not exist and also requests States Parties to support the implementation of the World Heritage and Sustainable Tourism Programme;

11. Further requests the World Heritage Centre to report biennially on the progress of the implementation of the Programme;

12. Notes with appreciation the launch of the Programme foreseen at the 40th Anniversary of the World Heritage Convention event in Kyoto, Japan, in November 2012

1. Having examined Document WHC-10/34.COM/INF.5F.1 and WHC-10/34.COM/INF.5F.3,

2. Highlighting that the global tourism sector is large and rapidly growing, is diverse and dynamic in its business models and structures, and the relationship between World Heritage and tourism is two way: tourism, if managed well, offers benefits to World Heritage properties and can contribute to cross-cultural exchange but, if not managed well, poses challenges to these properties and recognizing the increasing challenges and opportunities relating to tourism;

3. Expresses its appreciation to the States Parties of Australia, China, France, India, Sweden, Switzerland and the United Kingdom, and to the United Nations Foundation and the Nordic World Heritage Foundation for the financial and technical support to the World Heritage Tourism Programme since its establishment in 2001;

4. Welcomes the report of the international workshop on Advancing Sustainable Tourism at Natural and Cultural Heritage Sites (Mogao, China, September 2009) and adopts the policy orientation which defines the relationship between World Heritage and sustainable tourism ( Attachment A );

5. Takes note of the evaluation of the World Heritage Tourism Programme by the UN Foundation, and encourages the World Heritage Centre to take fully into account the eight programme elements recommended in the draft final report in any future work on tourism ( Attachment B );

6. Decides to conclude the World Heritage Tourism Programme and requests the World Heritage Centre to convene a new and inclusive programme on World Heritage and Sustainable Tourism, with a steering group comprising interested States Parties and other relevant stakeholders, and also requests the World Heritage Centre to outline the objectives and approach to implementation of this programme, drawing on the directions established in the reports identified in Paragraphs 4 and 5 above, for consideration at the 35th session of the World Heritage Committee (2011);

7. Also welcomes the offer of the Government of Switzerland to provide financial and technical support to specific activities supporting the steering group; further welcomes the offer of the Governments of Sweden, Norway and Denmark to organize a Nordic-Baltic regional workshop in Visby, Gotland, Sweden in October 2010 on World Heritage and sustainable tourism; and also encourages States Parties to support the new programme on World Heritage and Sustainable Tourism including through regional events and the publication of materials identifying good practices;

8. Based upon the experience gained under the World Heritage Convention of issues related to tourism, invites the Director General of UNESCO to consider the feasibility of a Recommendation on the relationship between heritage conservation and sustainable tourism.

Attachment A

Recommendations of the international workshop

on Advancing Sustainable Tourism at Natural and Cultural Heritage Sites

Policy orientations: defining the relationship between World Heritage and tourism

1. The tourism sector

The global tourism sector is large and rapidly growing, is diverse and dynamic in its business models and structures.

Tourists/visitors are diverse in terms of cultural background, interests, behaviour, economy, impact, awareness and expectations of World Heritage.

There is no one single way for the World Heritage Convention , or World Heritage properties, to engage with the tourism sector or with tourists/visitors.

2. The relationship between World Heritage and tourism

The relationship between World Heritage and tourism is two-way:

a. World Heritage offers tourists/visitors and the tourism sector destinations

b. Tourism offers World Heritage the ability to meet the requirement in the Convention to 'present' World Heritage properties, and also a means to realise community and economic benefits through sustainable use.

Tourism is critical for World Heritage:

a. For States Parties and their individual properties,

i. to meet the requirement in the Convention to 'present' World Heritage

ii. to realise community and economic benefits

b. For the World Heritage Convention as a whole, as the means by which World Heritage properties are experienced by visitors travelling nationally and internationally

c. As a major means by which the performance of World Heritage properties, and therefore the standing of the Convention , is judged,

i. many World Heritage properties do not identify themselves as such, or do not adequately present their Outstanding Universal Value

ii. it would be beneficial to develop indicators of the quality of presentation, and the representation of the World Heritage brand

d. As a credibility issue in relation to: i. the potential for tourism infrastructure to damage Outstanding Universal Value

i. the threat that World Heritage properties may be unsustainably managed in relation to their adjoining communities

ii. sustaining the conservation objectives of the Convention whilst engaging with economic development

iii. realistic aspirations that World Heritage can attract tourism.

World Heritage is a major resource for the tourism sector:

a. Almost all individual World Heritage properties are significant tourism destinations

b. The World Heritage brand can attract tourists/visitors,

i. the World Heritage brand has more impact upon tourism to lesser known properties than to iconic properties.

Tourism, if managed well, offers benefits to World Heritage properties:

a. to meet the requirement in Article 4 of the Convention to present World Heritage to current and future generations

b. to realise economic benefits.

Tourism, if not managed well, poses threats to World Heritage properties.

3. The responses of World Heritage to tourism

The impact of tourism, and the management response, is different for each World Heritage property: World Heritage properties have many options to manage the impacts of tourism.

The management responses of World Heritage properties need to:

a. work closely with the tourism sector

b. be informed by the experiences of tourists/visitors to the visitation of the property

c. include local communities in the planning and management of all aspects of properties, including tourism.

While there are many excellent examples of World Heritage properties successfully managing their relationship to tourism, it is also clear that many properties could improve:

a. the prevention and management of tourism threats and impacts

b. their relationship to the tourism sector inside and outside the property

c. their interaction with local communities inside and outside the property

d. their presentation of Outstanding Universal Value and focus upon the experience of tourists/visitors.

a. be based on the protection and conservation of the Outstanding Universal Value of the property, and its effective and authentic presentation

b. work closely with the tourism sector

c. be informed by the experiences of tourists/visitors to the visitation of the property

d. to include local communities in the planning and management of all aspects of properties, including tourism.

4. Responsibilities of different actors in relation to World Heritage and tourism

The World Heritage Convention (World Heritage Committee, World Heritage Centre, Advisory Bodies):

a. set frameworks and policy approaches

b. confirm that properties have adequate mechanisms to address tourism before they are inscribed on the World Heritage List

i. develop guidance on the expectations to be include in management plans

c. monitor the impact upon OUV of tourism activities at inscribed sites, including through indicators for state of conservation reporting

d. cooperate with other international organisations to enable:

i. other international organisations to integrate World Heritage considerations in their programs

ii. all parties involved in World Heritage to learn from the activities of other international organisations

e. assist State Parties and sites to access support and advice on good practices

f. reward best practice examples of World Heritage properties and businesses within the tourist/visitor sector

g. develop guidance on the use of the World Heritage emblem as part of site branding.

Individual States Parties:

a. develop national policies for protection

b. develop national policies for promotion

c. engage with their sites to provide and enable support, and to ensure that the promotion and the tourism objectives respect Outstanding Universal Value and are appropriate and sustainable

d. ensure that individual World Heritage properties within their territory do not have their OUV negatively affected by tourism.

Individual property managers:

a. manage the impact of tourism upon the OUV of properties

i. common tools at properties include fees, charges, schedules of opening and restrictions on access

b. lead onsite presentation and provide meaningful visitor experiences

c. work with the tourist/visitor sector, and be aware of the needs and experiences of tourists/visitors, to best protect the property

i. the best point of engagement between the World Heritage Convention and the tourism sector as a whole is at the direct site level, or within countries

d. engage with communities and business on conservation and development.

Tourism sector:

a. work with World Heritage property managers to help protect Outstanding Universal Value

b. recognize and engage in shared responsibility to sustain World Heritage properties as tourism resources

c. work on authentic presentation and quality experiences.

Individual tourists/visitors with the assistance of World Heritage property managers and the tourism sector, can be helped to appreciate and protect the OUV of World Heritage properties.

Attachment B

Programme elements recommended by the Draft Final Report of the Evaluation of the World Heritage Tourism Programme by the UN Foundation:

1. Adopt and disseminate standards and principles relating to sustainable tourism at World Heritage sites;

2. Support the incorporation of appropriate tourism management into the workings of the Convention ;

3. Collation of evidence to support sustainable tourism programme design, and to support targeting;

4. Contribution of a World Heritage perspective to cross agency sustainable tourism policy initiatives;

5. Strategic support for the dissemination of lessons learned;

6. Strategic support for the development of training and guidance materials for national policy agencies and site managers;

7. Provision of advice on the cost benefit impact of World Heritage inscription;

8. Provision of advice on UNESCO World Heritage branding.

1. Having examined Documents WHC-09/33.COM/5A, WHC- 09/33.COM/INF.5A.1, WHC-09/33.COM/INF.5A.2, and WHC-09/33.COM/INF.5A.3 ,

2. Recalling Decision 32 COM 5 adopted at its 32nd session (Quebec City, 2008),

3. Takes note with appreciation of the activities undertaken by the World Heritage Centre over the past year in pursuit of the Committee's five Strategic Objectives;

4. Takes also note of the findings of the study undertaken by UNESCO's Internal Oversight Service on the mapping of the workload of the World Heritage Centre presented in Document WHC-09/33.COM/INF.5A.3;

5. Notes with satisfaction that the World Heritage Centre is working with the secretariats of intergovernmental committees of related conventions such as the Convention for the Safeguarding of Intangible Cultural Heritage , and the Convention for the Protection of the Underwater Cultural Heritage-2001 and recommends that such cooperation be encouraged as this would further strengthen the work of the Centre;

6. Requests the World Heritage Centre to prepare a document on the World Heritage Convention and its cooperation and exchange with other conventions and programmes in the field of cultural heritage for discussion at the 34th session of the World Heritage Committee (2010);

7. Also requests the World Heritage Centre, in future reports on activities undertaken, to further strengthen the information and analysis available to States Parties by:

a) Retaining the current format to report activities and including an update on progress with implementing the Committee's decisions,

b) Describing the criteria by which the World Heritage Centre makes decisions as to which activities under the Convention it undertakes,

c) And including, on a discretionary basis, analysis of strategic issues and new directions;

8. Further requests the World Heritage Centre to produce, on an experimental basis, an indexed audio verbatim recording of the proceedings of the 33rd Session in addition to the standard summary records (as produced since the 26th session of the World Heritage Committee);

9. Notes the outline provided by the World Heritage Centre of its roles and the roles of the Advisory Bodies and agrees that this topic be further discussed at the 34th session of the Committee in 2010 under a separate agenda item;

10. Requests furthermore the World Heritage Centre to outline the forward direction of the World Heritage thematic programmes and initiatives, to enable an understanding of how these themes connect with and integrate into general programmes, and how they might be resourced;

11. Notes that the Centre already proactively engages women in its Heritage Programmes in Asia, Africa and the Caribbean as part of its gender balance policy and the provision of equal opportunity to all, and recommends that gender balance and community involvement be prioritized in the Centre's programmes;

12. Adopts the World Heritage Thematic Programme on Prehistory presented in Annex 1 of document WHC-09/33.COM/5A ;

13. Requests the World Heritage Centre to reconsider the term "prehistory", to better recognize the continuing cultures of indigenous communities, to ensure global representation in the identification and conservation of related properties, and to present a report on progress in developing an Action Plan on Prehistory and World Heritage at its 34th session in 2010;

14. Notes with concern the ongoing destruction of some of these fragile sites, including the recent destruction of the Rock Art sites of Tardrat Acacus in Libya, and requests the State Party to take immediate action and other measures as necessary to address the problem in consultation with the World Heritage Centre and to invite a joint World Heritage Centre / ICOMOS mission;

15. Expresses its gratitude to the Governments of Bahrain, South Africa and Spain for the financial and technical support for the various international scientific encounters, and recognizes the proposal of the Government of Spain in establishing a centre for the research of Prehistory;

16. Recalling the Decision of the World Heritage Committee 31 COM.21C to carry out a programme of sustainable development concerning the conservation of earthen architecture, thanks the Governments of Italy and France for their support of the programme on earthen architecture in Africa and the Arab States in particular, and requests the potential financial donors and the States Parties to support the implementation of activities and further requests the World Heritage Centre to submit a progress report at its 35th session in 2011;

17. Takes note of the progress report on the World Heritage Tourism Programme;

18. Thanks the Governments of Australia, China, France, India, Switzerland and United Kingdom, who have worked in close collaboration with the World Heritage Centre and the Advisory Bodies, the World Tourism Organization and other partners, for contributing to the Initiative of Sustainable Tourism;

19. Expresses its gratitude to the Governments of Australia and China for the organization of a workshop on sustainable tourism at the World Heritage site, Mogao Caves, China, in September-October 2009 and requests that the following elements be submitted to the Committee for examination at its 34th session in 2010:

a) A report on the workshop,

b) The subsequent recommendations of the workshop regarding the adoption of best practices policy guidance, and concerning the changes proposed for the Operational Guidelines for the implementation of the World Heritage Convention ,

c) A document concerning the progress of the World Heritage Programme on Tourism;

20. Finally requests the Director of the World Heritage Centre to identify supplementary sources of funding to put into place a sufficient number of staff and resources at the World Heritage Centre and the Advisory Bodies in order to continue to efficiently contribute to the resolution of problems related to World Heritage conservation.

XVII.8 The Secretariat provided the following justifications for the selection:

- Tourism - growing threats on World Heritage sites from tourism which, if sustainably managed could offer socio-economic development opportunities;

- Forests - since close to 60 of the natural sites on the World Heritage List are forests and that the lessons being learned from the large-scale UNESCO-UN Foundation projects in the tropical forest sites in the Democratic Republic of the Congo can serve as case studies to enrich the programme;

- Cities - since close to 200 of the cultural sites on the List are historic centres or entire cities, and because 20% of the Fund's international assistance have served to address the challenge of urban heritage conservation;

- Earthen structures - since some 30 of the cultural sites on the List are included in this category, and due to the particularity of conservation of earthen heritage, and threats.

XVII.10 The Committee expressed its appreciation for the clarity of the presentation and the justifications provided. Indicating strong support for the overall programming approach, the Committee however indicated the need for the programme to respond to the priorities established by the Committee and to create strong links with the results of the Global Strategy actions and Periodic Reporting. The Committee approved the four proposed themes of the programmes in this first series of initiatives and authorized the Centre to proceed in their development.

- Research article

- Open access

- Published: 19 July 2021

Joint development of cultural heritage protection and tourism: the case of Mount Lushan cultural landscape heritage site

- Zhenrao Cai 1 ,

- Chaoyang Fang ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-6695-7169 1 , 2 , 5 ,

- Qian Zhang 1 &

- Fulong Chen 3 , 4

Heritage Science volume 9 , Article number: 86 ( 2021 ) Cite this article

8091 Accesses

31 Citations

Metrics details

A Correction to this article was published on 08 November 2021

This article has been updated

The joint development of cultural heritage protection and tourism is an essential part of sustainable heritage tourism. Mount Lushan in China is such a site which in the past has had shortcomings in heritage protection and heritage tourism marketing. The present research addresses this issue by using digital technologies such as oblique aerial photography, 3D laser scanning technology, and 360 degrees panorama technology to digitize the Mount Lushan cultural landscape heritage site, integrating all elements to create a virtual tourism subsystem. It provides users with a virtual experience of cultural landscape heritage tourism and promotes cultural landscape tourism marketing. In addition, tourist flow and environmental subsystems were built through the integration of Internet of Things (IoT) technology and analytical models. The tourist flow subsystem can help managers to regulate tourist flow according to the tourist carrying capacity threshold. Managers can also conduct environmental health assessment and management through the "pressure-state-response" model provided by the environmental subsystem. Finally, a comprehensive platform was developed based on the system concept, which integrated the three subsystems and their functions, and developed different versions to provide a visual platform for tourists and managers. This study provides a new model for the joint development of cultural heritage protection and tourism activities.

Introduction

Cultural heritage tourism is an increasingly prominent form of tourism globally, bolstered by heritage listings of UNESCO [ 1 ]. Built environment or other forms of heritage are often regarded as a focus of social and economic development [ 2 ], and the tourism industry can be a driving force to promote heritage protection. Cultural heritage management departments generally assume asset ownership and daily management tasks, while the tourism industry is responsible for product development and marketing [ 3 ]. However, poor management of cultural heritage may lead to its degradation. Heritage sites may be damaged by fire or natural disasters, or by human-induced factors [ 4 ]. For example, the large flow of people typical of popular tourist destinations may indirectly damage the principal tangible and intangible cultural value of a heritage site [ 5 ]. It is thus imperative to strengthen the protection and management of heritage. The Internet has become an important marketing tool for tourism promotion [ 6 ], mainly because it can speed up information dissemination. However, whether the website efficiently conveys travel information or effectively promotes destinations is often uncertain as designers tend to focus on aesthetics rather than content [ 7 ]. In addition, the quantity and quality of information will affect the time it takes for users to visit the website pages, thereby further restricting the development of the tourism industry.

The "digitalization" of heritage can provide a suitable way to address these issues. Field surveys and mapping, photo files, and data collection are traditional methods of acquiring cultural heritage data, and these results have become an essential foundation for heritage protection [ 8 ]. Novel and advanced technologies, such as digital photogrammetry and spectral imaging, are becoming more widely employed in heritage science and are often used to comprehensively record, understand and protect historical relics and artworks [ 9 ]. Some examples of these advances include the use of drones to obtain high-resolution images and using the data for 3D modeling [ 10 ]; using 360 degrees panorama technology to obtain panoramic photos [ 11 ]; or using terrestrial laser scanners to obtain point clouds. Such observations can be used to generate highly accurate models or drawings [ 12 ]. GIS also plays a vital role in protecting and utilizing cultural heritage. Using the Web and mobile GIS support, cultural heritage data, such as text, audio, or video stories, location information, and images, can be obtained through portable devices. GIS has unique advantages for data collection, storage, and manipulation of datasets [ 13 ]. By integrating historical building information models and 3D-GIS attribute data, the visibility and interactivity of the information models used in cultural heritage sites can be enhanced [ 14 ]. Virtual reality (VR) technology also has exceptional value in tourism marketing and cultural relic protection, involving computer graphic rendering, artificial intelligence, networks, and sensor technology, and can virtually reconstruct and simulate cultural heritage. These are examples of effective "digital protection" of cultural heritage [ 15 ] which can also assist in attracting more tourists [ 16 ].

In addition to the digitization of heritage resources, the flow of visitors and its associated impact to the environment of heritage sites is also intimately related to heritage protection and tourism development, and this factor may also be assisted by advanced technology. The Internet of Things (IoT) can be used to monitor and manage the tourist flow, for example, beam sensors can be employed to count the number of tourists and use these numbers to improve tourist management [ 17 ]. The adoption of video monitoring technology in combination with GIS can be used to analyze and visualize the spatial distribution of pedestrian numbers and flow in different areas, providing a strong foundation for tourist flow management [ 5 ]. Ground laser scanning technology, sensor monitoring technology, and digital photography can be used to monitor and manage the local environment [ 18 , 19 , 20 ], and IoT technology can dynamically evaluate whether environmental conditions are suitable to protect cultural heritage.

Such digital technologies have helped to promote the modernization of heritage tourism. Many studies have considered these issues from discrete and separated aspects such as heritage protection, tourism marketing, and tourism management, but less attention has given to the integration of heritage protection and tourism development. Cultural heritage protection and tourism are interdependent by nature [ 21 ], and a holistic approach to cultural heritage protection and tourism management is likely to be more effective for all concerned [ 22 ]. This research will explore a sustainable development model of cultural heritage to construct a bridge between cultural heritage protection and tourism development via an integrated platform approach.

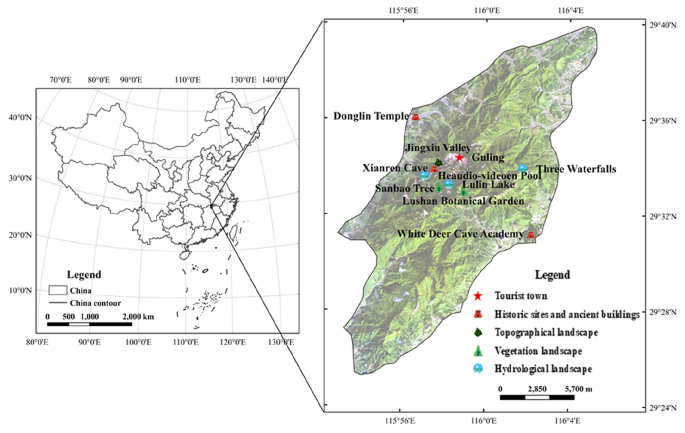

Mount Lushan (29°28'-29° 40' N, 115°50'-116°10' E) is located in Lushan County, Jiujiang City, Jiangxi Province, China. Figure 1 shows the location and main attractions of Mount Lushan. It has a rich cultural and natural heritage and is known for its beautiful and unique scenery. The mountains, rivers, and lakes of Mount Lushan blend into landscape tapestry, and Buddhist, Taoism, Christianity, Catholicism, and Islam coexist here. It is known as a mountain of culture, education, and politics. Historically, it has inspired artists, philosophers, and thinkers and inspired many famous works of art. Thirty churches and schools built in the 1920s remain, and 600 villas are influenced by the architectural styles of 18 countries. It is a site of historical importance to the Chinese Nationalist Party and the Chinese Communist Party, and many major meetings are still held here. It is a world-famous cultural landscape heritage site and one of the spiritual centers of Chinese civilization. Its main area covers 30,200 hectares, and its buffer area is greater than 50,000 hectares. Ontological areas and buffer zones include ancient buildings, ruins, modern villas, stone carvings, alpine plants, waterfalls, and streams. Mount Lushan in its entirety for the conservation of the subtropical forest ecosystem and historical sites [ 23 ]. These elements fully demonstrate the cultural and natural elements of the Mount Lushan World Heritage Site. Mount Lushan is listed as one of the top ten most famous mountains in China in 2003 and was rated as a national 5A Tourist attraction (5A is the highest level of China's tourist scenic spots, representing the level of China's world-class quality scenic spots) in 2007. These accolades have stimulated the rapid development of tourism in Mount Lushan, attracting tens of millions of tourists every year.

Geographical location and main attractions of Mount Lushan

However, online and field research on Mount Lushan has revealed significant obstacles to the sustainable development of cultural heritage tourism in this area. On one hand, Mount Lushan promotes and displays the cultural heritage landscape through tourism websites, such as the "China Lushan Network" ( http://www.china-lushan.com/ ). This approach only introduces this heritage site in a two-dimensional way (through pictures and text). Although there is a virtual tour section, tourists can only browse a few scenic spots via panoramic views. The possible immersion and interaction, and thus, the virtual experience, is not adequate or conducive to tourism marketing in the heritage site. On the other hand, the increased influx of tourists has given rise to a series of ecological and environmental problems [ 23 , 24 ]. There is a lack of equipment to monitor the flow of passengers and environmental quality, and there is little visual management information or monitoring capability of tourist flow and environmental information. The quantity and quality of information available at a heritage site directly affects the time spent by users visiting the website and also affects the satisfaction of users (or tourists) [ 25 , 26 ].

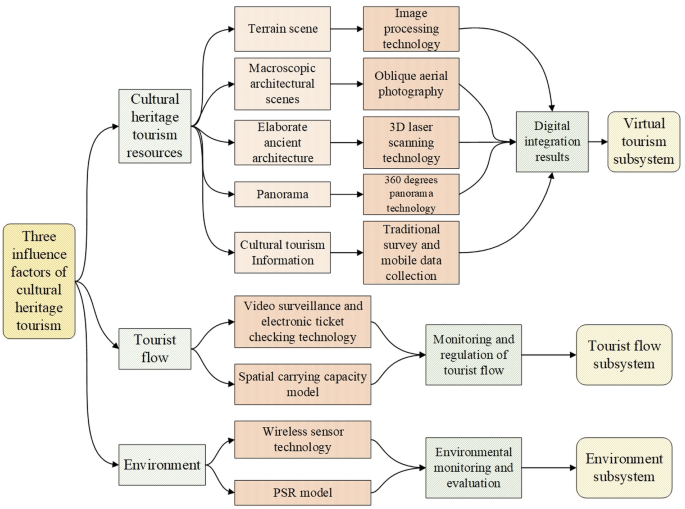

Technologies and models

In the method of system thinking [ 27 ], a cultural heritage tourism system can be divided into cultural heritage tourism resource elements, tourist flow elements, and environmental elements. Here we construct subsystems for each of these elements. Our approach involves the digitization of cultural landscape resources to realize a virtual cultural heritage tourism and marketing system. This subdivision into a virtual tourism subsystem, tourist flow subsystem, and environment subsystem build a complete foundation for cultural heritage protection and tourism development. The technical flow chart of the holistic construction of these three subsystems is shown in Fig. 2 .

Technical process of the subsystems in the holistic cultural heritage protection and tourism development

Digitalization technologies

Different digital technologies were adopted for cultural tourism information, such as macro-topographic scenes, ancient buildings, panoramic views which considered the complex landscape composition, diverse tourism elements, and the wide geographical diversity of Mount Lushan. The comprehensive application of multiple digitization technologies avoids the deficiencies associated with a single digitization technology and allows large cultural landscape heritage sites to be comprehensively and systematically digitized.

For the large-scale terrain scene of Mount Lushan, it was necessary to purchase 350 km 2 of digital orthophoto map (DOM) data and digital elevation model (DEM) data from the government and use image processing technology to process the original data.

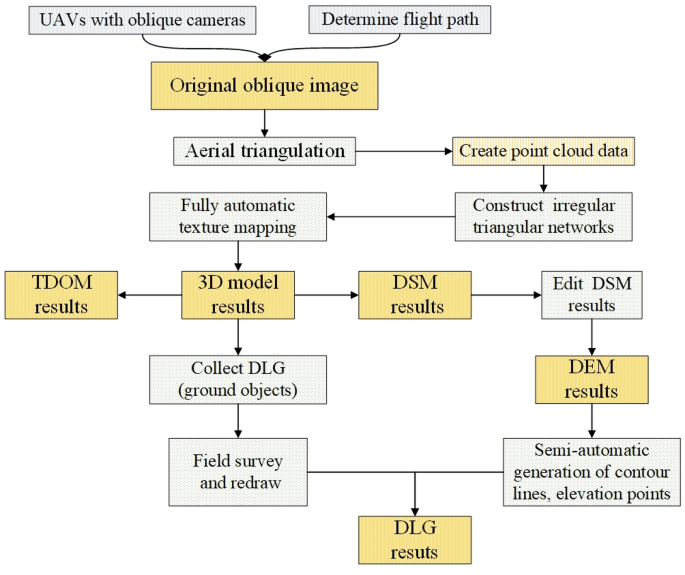

We used an integrated production technology process of 3D models, digital line graphs (DLG), DEM, and digital orthopedic maps (TDOM). The flow chart of this process is shown in Fig. 3 . First, aerial photography was used to obtain oblique photography images [ 28 ]. The flight route and altitude of unmanned aerial vehicles (UAV) were planned, the aerial photography area was delineated, and then the UAV was equipped with a digital oblique camera, and stereo images were then extracted from the UAV videos for aerial triangulation [ 29 ]. Next, 3D models were constructed by creating point clouds, constructing irregular triangulations, and performing texture mapping. The 3D model results were edited to obtain the digital surface model (DSM) results and TDOM results. The DEM results were then obtained by editing the DSM results, and the original DLG data were collected from the 3D models. The DLG data were further supplemented and improved, and were redrawn through field surveys to improve their accuracy. Finally, contour lines and elevation points were generated to supplement the line elements in the DLG supported by the DEM results.

Flow chart of the integrated production technology process

Terrestrial laser scanners allow rapid scans of measured objects. They can directly obtain high-precision scanning point clouds, efficiently carrying out 3D modeling and virtual reproduction of historic buildings [ 30 ]; here, we applied this approach to obtain point clouds of historical buildings in Mount Lushan. Using the point cloud data, the Smart3D software was used to perform fine 3D modeling.

360 degrees panorama technology can yield a 360 degrees horizontal viewing angle and a 180 degrees vertical viewing angle, and can integrate 360 degrees panoramas in a virtual environment [ 11 ]. We employed this technology, using a digital camera to take initial images, then using Photoshop for image stitching to form spherical and cube panoramas.

This study also used traditional data collection methods such as digital photography, digital video shooting, digital recording, image, and text scanning, and interview records to collect cultural heritage resource information. We additionally employed a mobile collection method, using personal digital assistants (PDAs) to obtain real-time wireless communication with the back-end system through the wireless data transmission network, and sent the collected cultural heritage coordinate data to the back-end system in real-time [ 31 ].

Monitoring technologies

We employed IoT technology to monitor and manage the flow of tourists and the environmental conditions in the cultural heritage landscape. Video surveillance technology and electronic ticket checking technology were used to monitor travel traffic, and Internet technology was used to visualize surveillance data. First, cameras were set up at the entrance and exit of the scenic spot and near its main attractions to monitor the flow of tourists. Electronic ticketing technology was used to measure the total number of tourists entering the scenic spot. Then, an established tourist flow subsystem was used to process tourist video data and obtain statistics of the flow of tourists in real-time. In addition, we used wireless sensor technology for environmental monitoring in scenic spots [ 32 ]. We installed sensors to measure the levels of harmful oxygen ion concentrations, sulfur dioxide, temperature, and humidity. Finally, we connected the environmental data with the established environment subsystem to display the environmental status of the cultural heritage site in real-time.

To fully exploit the monitoring data, we applied several analytical models to strengthen cultural landscape management. Specifically, we combined a spatial carrying capacity model with the tourist flow monitoring data and the "pressure-state-response" (PSR) model for environmental monitoring of the cultural landscape heritage site.

The spatial carrying capacity model was adopted to represent the tourist carrying capacity of Mount Lushan. The model refers to the number of tourist activities that can be effectively accommodated by tourism resources within a certain period and still maintain the quality of the resource. It can also reflect the capacity of the cultural heritage landscape, which can be measured from the aspects of planar capacity and linear capacity.

The planar calculation method applies to areas with relatively flat terrain and relatively uniform distribution of scenic spots and reception facilities [ 33 ], expressed as:

where C 1 is the spatial carrying capacity (persons/day, i.e., the number of persons suitable for the scenic spot every day), A is the scenic spot (m 2 ), A 0 is the reasonable area occupied per capita (m 2 ), and T is the average daily opening time (hours). Although the scenic spot is open 24 h per day, tourists are mainly visiting during the daytime, so T is set for 8 h in our study. t 0 is the average time required for visitors to visit the scenic spot (h).

The linear capacity calculation method is suitable for tourism sites along a path, with the resource space capacity expressed as:

If the path is incomplete and the entrance and exit are in the same position, tourists can only return by retracing their steps on the original path. In this case, the spatial carrying capacity formula becomes:

In Eqs. ( 2 ) and ( 3 ), C 2 and C 3 both refer to spatial carrying capacity (persons /d). L is the length of the path (m), L 0 is the length of reasonable possession per capita (m), and t 1 is the return time along the original route (h). The total number of tourists calculated using the area method and the line method constitutes the resource space capacity of the cultural heritage landscape.

The PSR model was first proposed in 1979 to study environmental problems. It has become a commonly used model to evaluate environmental quality [ 34 ]. In the PSR model, "P" refers to the pressure index, which is used to describe the pressure applied to the ecological environment under the influence of human activities. "S" refers to the state index, which is used to describe the status of the ecological environment. "R" refers to the response indicator, which describes the positive management actions taken by human beings towards the ecological environment. The PSR model answers three basic sustainable development questions: what happened, why it happened, and what will happen in the future.

Our study used this comprehensive evaluation index to reflect the ecosystem quality of Mount Lushan. A weighted summation method was used to perform the calculation [ 35 ]:

where Z represents the comprehensive evaluation index, X i is the normalized value of a single index, and Y i is the normalized weight of the evaluation index.

Case study verification

Heritage digitization and visualization, multiple types of digitization.

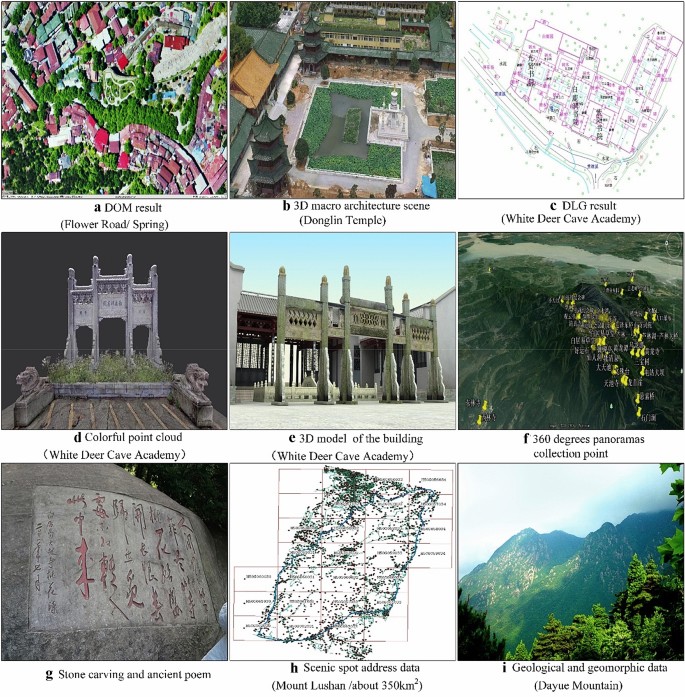

Digitized results are shown in Fig. 4 a–i. For the 350 km 2 DOM, image fusion, color uniformity, stitching, and resampling were used to generate DOM data with a resolution of 0.2 m (Fig. 4 a shows the spring scene in Guling). Using oblique aerial photography, we made 3D models of White Deer Cave Academy, Donglin Temple, Guling, and Mao Zedong Poetry Garden. The generated large-scale scene 3D model has high accuracy, for example, the accuracy of the 3D model of Donglin Temple is 0.06 m (Fig. 4 b). The DLG data collected only has a small margin of error that satisfies the accuracy of a 1/1000 scale map (such as White Deer Cave Academy shown in Fig. 4 c).

Digitization results for selected spots in Mount Lushan

Education, politics, architecture, natural scenery, religion, and other elements of typical cultural heritage landscapes were considered when conducting the digital modeling process. This process was based on 3D laser scanning, 3D modeling, 360-degree panoramas, and other technologies. These results are shown in Fig. 4 d–f. 3D laser scanner was used to model ancient buildings such as the White Deer Cave Academy, Mao Zedong Poetry Garden, and Xianren Cave and obtain delicate point clouds of the buildings. The point clouds contain important appearance features (as shown in Fig. 4 d), such as the characteristic feature lines. The elevation, plan, and cross-sectional views of ancient buildings generated from the point clouds were combined with the collected DLG data to generate a 3D model with fine texture and spatial characteristics (Fig. 4 e). These 3D models can provide accurate and detailed information for cultural heritage protection. UAVs and ground collection equipment were used to obtain aerial and ground panoramas of the cultural landscape heritage site in each season, and a total of 304 main scenic spots in Mount Lushan were collected (Fig. 4 f).

We collected and digitized materials from Taoist and Buddhist cultures, including ancient poems and paintings, ancient books, ancient cultural relics, historical narratives, and written accounts by using traditional data collection methods. Figure 4 g shows a stone carving, which is a poem (its title is "Peach Blossoms in Dalin Temple") written by a famous ancient Chinese poet. Other data on the heritage site (scenic spots, traffic, shopping, accommodations, entertainment, tourist facilities, geological data, vertical zonal soil profiles, plant communities) were collected and digitized using mobile data collection. Figure 4 h displays 7,128 geographical names and addresses covering an area of about 350 km 2 were collected. Figure 4 i shows major geological and geomorphologic features of Xiufeng Mountain.

Virtual tourism of Mount Lushan

From the digitized results, a fundamental geographic information database and a cultural heritage resource database were constructed. The SuperMap software was then used to develop the virtual tourism subsystem. This software can manage a large amount of data, can support directly imported data, has high-quality rendering capabilities, and can optimize the scene. The Lushan virtual tourism subsystem was developed into a display platform integrating sound, text, images, 3D models, maps, and various human–computer interaction technologies.

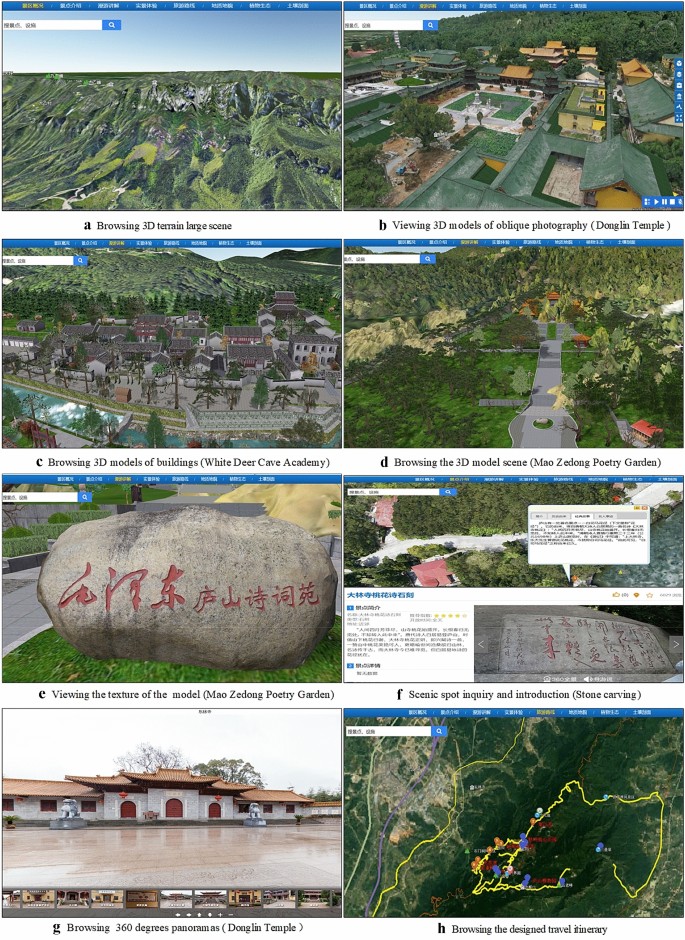

This subsystem has the following functions of 3D scene browsing:

Generation of a 3D terrain scene: the high-resolution DEM data of about 350 km 2 superimposes with the multi-temporal DOM to generate a 3D terrain scene of Mount Lushan. The "majestic, peculiar and beautiful" natural landscape features of the cultural heritage site can clearly be seen in Fig. 5 a.

Browsing the virtual scene of the virtual tourism subsystem

Generation of 3D architectural scenes: the original files of the oblique photography model data included many fragmented files, and the amount of data was enormous. We used SuperMap to process oblique photography models, including generating configuration files, compressing textures, simplifying models and type conversion, meeting the needs of viewing oblique photography models on web pages, and achieving a smooth browsing experience. We located and integrated the processed 3D model of Donglin Temple into the scene (Fig. 5 b). For the 3D model generated by laser scanning, we imported the constructed model data into the data engine provided by SuperMap and integrated it into the scene (Fig. 5 c).

Integration of different types of 3D models: the oblique photographic and geometric modeling data were imported into the terrain scene and accurately matched. By controlling the visibility of layers under different viewing angles, seamless switching between terrain scenes and 3D model data was realized. When users viewing the model from a distance, the subsystem can display the DSM; when viewing it at a close distance, the oblique photographic model is displayed on the periphery, and the internal core building is loaded with an intricately detailed 3D model (see Fig. 5 d). Users can also continue to zoom in to view the fine texture formed by the laser scan data (Fig. 5 e). The subsystem also sets the number of objects and layers in the scene under different viewing angles to reduce the memory and video memory usage of the system to ensure the fluency and stability of the subsystem and speed up the browsing speed of the scene.

Assisted by GIS, the subsystem has the functions of query, recommendation, and popular science. When the user opens the subsystem interface and enters the query keyword through the interactive interface, the result is displayed on the left sidebar and in the 3D scene. The query results will be introduced in pictures and texts (for example, Fig. 5 f, which shows a picture of a stone carving, and its poem). Based on the collected geological geomorphology and vegetation ecological data (Fig. 4 i), we set up the query and positioning function of geological relics, vegetation, and other attribute information in the subsystem, providing 3D elements, pictures, text, and other display elements, which is helpful to popularize the natural background knowledge of the heritage site to tourists. The subsystem provides an automatic roaming function for famous scenic spots and designed several common roaming routes. When performing automatic roaming, it will be supplemented by voice introduction. A "virtual tour guide" is implemented, and the user can control the broadcast process of the route at any time. Figure 5 b shows a roaming scene, and the roaming operation symbol can be seen in the lower right corner. The subsystem can also simultaneously integrate panoramas. By clicking on the panoramic location in the scene, the 360 degrees panoramas of the current position is displayed as a pop-up (see Fig. 5 g). Using the scenic spot location data displayed in Fig. 4 h, we set up multiple travel planning routes in the subsystem (Fig. 5 h). When the user clicks on a specific route, the subsystem will display the route direction and scenic spots on the map to provide convenience for tourists with travel intentions.

The subsystem can provide a unique virtual experience through rich visual content. It can interact with users through query, tourism recommendations, science popularization, and other functions. It can allow to know Mount Lushan in advance, making it an effective marketing tool.

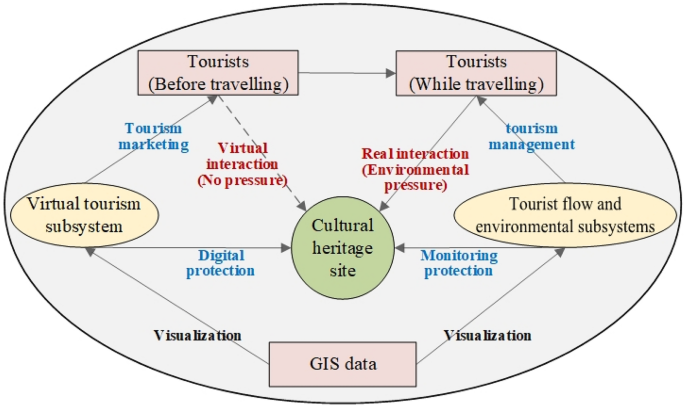

Monitoring and management of tourist flow and environment

When tourists enter a heritage site, they induce environmental pressure. Using our system, tourists can interact virtually before travelling without exerting direct pressure on the cultural heritage site. The virtual tourism subsystem can also help managers improve the protection of the heritage site and carry out tourism marketing. This system can provide better monitoring of tourist flow and the environment of the site, which can greatly assist managers with tourism management and heritage protection. The three subsystems share GIS data to provide a strong data-based foundation for visualization services. These processes are shown schematically in Fig. 6 .

Interaction of the three subsystems that improve the management of tourist flow and environmental monitoring of the cultural heritage site

Monitoring and regulation of tourist flow

We used video surveillance technology and electronic ticket checking technology to collect tourist information, built a tourist database, and integrated it with geographic information data (including the location and entrance of the scenic spots and major tour paths). The database is used to record and manage data and to calculate the number of people entering and leaving the scenic spot and the number of people staying in the scenic spot in real-time. We then developed s tourist flow subsystem, which mainly provides services for managers.

Managers can use the subsystem to monitor and manage the tourist flow of the cultural heritage site visually and provide travel services. When visitors buy tickets, their ID number and name will be associated with the identity of the e-ticket. The scope of their travel will be identified in the scenic area. When visitors enter the video surveillance area, face recognition information will be collected by the monitoring equipment, so the general location of the travelers can be identified through the ticket information and video information, and missing tourists can be quickly located to ensure safety.

The determination of tourist capacity thresholds can be vital to the scientific regulation and management of tourist flows within the cultural heritage site. We selected the main scenic spots and routes of Mount Lushan for analysis, and the parameters and results are shown in Tables 1 and 2 . The capacity of general scenic spots should be 100–400 square meters per person (based on the "Standards for the Master Planning of Scenic Spots" issued by the Ministry of Housing and Urban–Rural Development of China [ 36 ]). Guling is a tourist destination, but it is also a town with permanent residents, so we here assume that its reasonable per capita area is 100 m 2 /person. For other spots, we assume that the reasonable per capita living area is 400 m 2 /person. Using these assumptions, the tourist capacity of these scenic spots in Mount Lushan is 46,472 persons/d (Table 1 ). Since the Guling scenic spot has 21,400 permanent residents, the remaining capacity for visitors is thus 25,072 persons/d. The per capita area of tour routes calculated by the linear capacity calculation method is 5–10 m 2 /person. We choose a value in the middle of this range, 8 m 2 /person for our further analyses. The total tourist capacity of the three paths is 4734 persons/d according to this approach (Table 2 ).

The tourist flow subsystem integrates the number of tourists and GIS data and displays the number of people in each scenic spot by way of map visualization. Similarly, the tourist capacity threshold data of each scenic spot is displayed in the subsystem, and managers can compare the tourist flow real-time data with the tourist capacity threshold data. When the number of tourists in each route and scenic spot exceeds the tourist capacity threshold, the cultural heritage site manager can temporarily restrict ticket sales for overcrowded attractions and guide visitors to other areas. The tourist capacity threshold subsystem thus provides a strong data-based foundation for heritage protection and tourist flow pressure.

Monitoring and evaluation of the environment

We used IoT technology, wireless sensors, and GIS technology to monitor the environment. We first determined the geographic location of the monitoring site and installed the sensor to obtain atmospheric and environmental data through General Packet Radio Service (GPRS) data transmission equipment. Then we established an environmental database to integrate and manage various data resources to develop an environment subsystem that can analyze and express data and realize serving managers.

The subsystem provides a real-time visual management platform for managers that provides a visual map. Managers can use this map to monitor and understand the environment and weather conditions of each scenic spot in real-time to address any possible emergency environmental events in a timely manner.

This tool can also assist with longer-term management. The environmental database stores monthly or longer-period monitoring data and social and economic data. The subsystem can then integrate socio-economic data and annual monitoring data into the PSR model. Table 3 shows the original data of the PSR model, and the analysis results calculated by Eq. ( 4 ). As compared with 2017, the comprehensive index of environmental health in 2018 was higher (0.64) because the comprehensive index of response in 2018 was higher than in 2017. However, the pressure index in 2018 was lower than that in 2017. This is attributed to an increase in the number of permanent residents and tourists in 2018, as well as an increase in sulfur dioxide emissions; the combination of both factors has put more pressure on the environment. Future adjustment of the population capacity and better control of the discharge of pollutants could likely improve the comprehensive environmental index.

The analysis results of the PSR model (environmental health index) can be visualized in detail by the environmental subsystem for managers. The comprehensive evaluation results of the environment can play an important role in feedback and early warning. It encourages managers to carry out annual environmental assessments and take corresponding measures, which is conducive to the long-term environmental protection of the heritage site.

Construction of a comprehensive platform

Concept and method of construction.

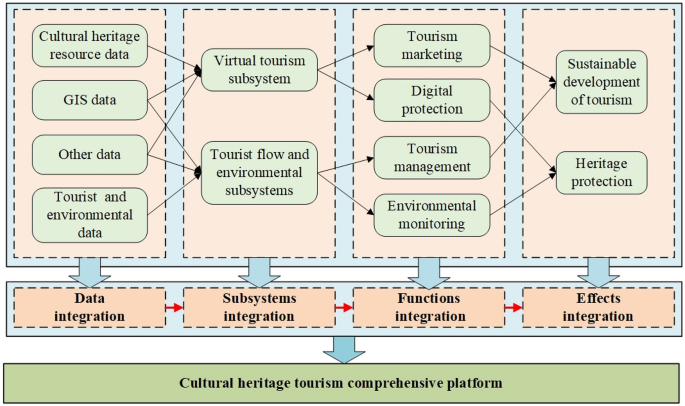

The relationship between heritage and tourism is problematic and intricate, and considering these factors separately is insufficient [ 37 ]. Synergies should be developed between tourism and heritage protection [ 38 ]. Our integrated system that considered virtual tourism, tourist flow, and environment subsystems is constructed by the integration of different data sources, which have the functions of tourism marketing, digital protection, and information service, and environment management. The interactivity of these different functions improve the overall tourism development and heritage protection. The effective integration of all subsystems allows the construction of a complete platform, detailed in Fig. 7 , which displays the path of "data integration-subsystems integration-functions integration-effects integration", thus our system integrates discrete data and subsystems to yield a comprehensive platform for cultural heritage tourism.

Path of the comprehensive platform construction

Products and a new mode

Our first step was to build a comprehensive database. We classified and selected multi-source data, set up a cultural heritage resource database, a GIS database, a tourist and environment database, and a tourism management database to realize the unified storage and management of the data in the cultural heritage tourism comprehensive database. This provided a seamless data interface which includes different types of essential service data for the construction of a comprehensive platform.

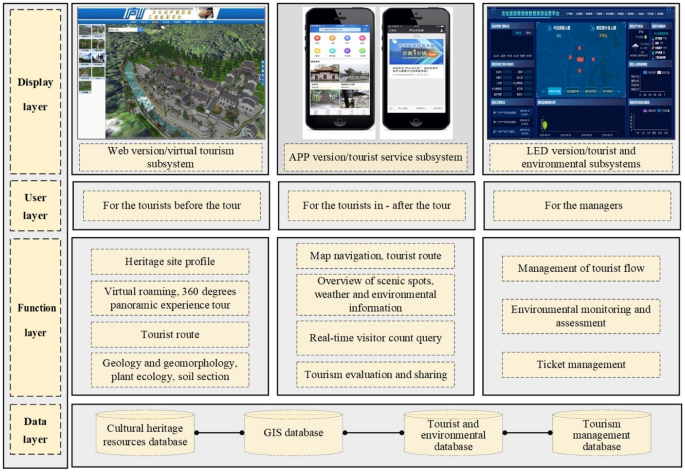

The comprehensive platform for Mount Lushan cultural heritage tourism using this complete database is displayed in Fig. 8 . It uses multiple display media (e.g., personal computer, smartphones, LED displays), multiple content presentation forms (3D models, maps, charts, text, audio), and multi-subsystem and multi-functional integration forms (virtual tourism subsystem, tourist flow, environment monitoring subsystem, tourist service subsystem, and corresponding functions), providing comprehensive cultural heritage services for tourists and management.

Information of each version

The functions displayed by different media terminals can meet the individual needs of users at different times and places. The Web version is intended for tourists to use before traveling, functioning as a virtual tourism subsystem. It can introduce the cultural heritage site, and can "educate" users to have a more responsible and respectful relationship with the cultural heritage site. It can help to attract potential tourists, as they can “virtually experience” the site before traveling. The LED version of the product is intended for managers, integrating the tourist flow subsystem and the environment subsystem. Managers can monitor tourists and the environment through the LED screen and can visually operate and manage the tourist capacity and environmental health based on the results of the tourist capacity model and PSR model. The smartphone-based application product is intended for tourists during and after travel. It integrates components of the functionality of both the Web-based and LED products to facilitate tourists in obtaining and sharing heritage site information. Tourists can get an overview of the heritage site, navigate the site via the maps and receive tourist recommendation services. They can also find information on the total number of tourists and environmental and weather information of heritage sites. Tourists can then arrange effective plans for their visit based on these functions. It also provides post-tour services such as evaluation of tourist attractions. These functions enrich the experience and satisfaction of tourists.

The comprehensive cultural heritage tourism platform and its corresponding products demonstrate a new paradigm of cultural heritage tourism. Our model can coordinate and integrate multiple key elements to improve the sustainable development of cultural heritage tourism through the combination of in-person and virtual tourism, the combination of service and management to meet the needs of different users, and the combination of heritage protection and tourism.

Results and discussion

The digitization of cultural heritage is becoming more critical, including intangible heritage [ 39 ], historical sites [ 40 ], archaeological sites [ 41 ]. We here developed and described a cultural heritage tourism subsystem, which applies a variety of technologies and methods (such as computer technology, IoT, photogrammetry, geographic information technology, VR technology, and environment assessment methods). We obtained a series of digital results and developed several digital products for tourism marketing and heritage protection.

We also integrated environmental assessment models to provide real-time and long-term assessment and management plans. We accounted for cultural heritage protection, tourism marketing, and management, and the development of cultural heritage tourism digital products. These products show the geographical characteristics of the heritage area, which is conducive to improved heritage protection and the sustainable development of tourism.

The salient point of our research is "integration", which is manifested by integrating multiple subsystems, and connecting themes of different perspectives (including cultural heritage protection, tourism marketing, management, and services) to provide a holistic system. Our important results and finding are now summarized.

(1) Through the use of comprehensive and diverse digital technologies, we obtained a wealth of digital results, including 3D large-scale terrain scenes, 3D cultural relic images, 360-degree panoramas, and pictures. This information was used to create a virtual tourism subsystem to display the regional characteristics of cultural landscape heritage sites through 3D scenes, popular science, and tourism recommendations to improve tourism marketing.

(2) IoT technology was combined with a tourist carrying capacity model and a PSR model to construct tourist flow and environmental subsystems. The tourist flow subsystem allows managers to monitor and manage the tourist flow using capacity models. The environmental subsystem allows the monitoring and management of the environment in real-time and non-real-time using an integrated PSR model.