An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

- Elsevier - PMC COVID-19 Collection

Evolution of international tourist flows from 1995 to 2018: A network analysis perspective

Yuhong shao.

a School of Tourism, Sichuan University, No. 24 South Section 1, Yihuan Road, Chengdu 610065, China

Songshan (Sam) Huang

b School of Business and Law, Edith Cowan University, Joondalup, WA 6027, Australia

Yingying Wang

Mingzhi luo.

Tourist arrivals and tourism revenues have been extensively studied to evaluate international tourist flows, whereas the structure and evolution of these flows have received less attention. Based on international tourist arrival data from 221 countries/regions during the period 1995–2018, this study applies network analysis to explore the structure and evolution of international tourist flows, and the roles and functions of countries/regions in the international tourist flow network. The results of this study reveal that the network density of international tourist flows is increasing. Countries/regions in Europe, East Asia and North America generally occupy a significantly important position within the international tourist flow network, especially Germany and China. Those geographically close countries/regions demonstrate the same or similar roles and positions in international tourism. This study has significant implications for tourist destination management and marketing.

- • We illustrated the necessity of exploring the structure of international tourist flows.

- • We evaluated the structure and evolution of international tourist flows among 221 countries/regions from 1995–2018.

- • We employed Network Analysis to explore the roles and functions of countries/regions.

- • Germany and China acted as the dominating outbound and inbound tourism markets respectively from the perspective of structure.

- • Geographically close countries/regions demonstrated the same or similar roles and positions in international tourism.

1. Introduction

International tourism has become a popular global leisure activity worldwide ( Keum, 2010 ). According to a report released by the World Tourism Organization (UNWTO), the magnitude of international tourist arrivals rose to 1.4 billion in 2018, ahead of the forecast by UNWTO ( UNWTO, 2019 ). Likewise, the revenues of international tourism increased from US $485.178 billion in 1995 to US $1.649 trillion in 2018 ( UNWTO, 2020 ). In this regard, international tourist flows have attracted the attention of both the global tourism industry and academic research ( Zhang, Li, & Wu, 2017 ). Previous research has mainly evaluated international tourist flows from the perspectives of tourist arrivals or tourism revenues (e.g., Balli, Balli, & Louis, 2016 ; Hall, 2010 ; Huang, Han, Gong, & Liu, 2019 ; Yang, Liu, & Li, 2018 ; Zhang et al., 2017 ).

Essentially, international tourism is a place-oriented activity with tourist flows across country borders ( Deng & Hu, 2018 ; Keum, 2010 ). However, few studies have focused on the structures of international tourist flows worldwide, especially the dynamic changes of these flows. According to Yang et al. (2018) , today's world order faces unprecedented backlash, as does the global tourism industry. Understanding the structure and evolution of the international tourist flows is conducive to the implications for the development of infrastructure, product, destination and others, as well as the management of tourism's impacts on society, environment and culture ( Lew & McKercher, 2006 ), which can be helpful for policymakers and tourism firms to improve market competitiveness and destination management.

Network analysis is an approach with a set of methods and tools to map and measure the patterns, flow and strength of relationships between actors ( Casanueva, Gallego, & García-Sánchez, 2014 ), and has been applied in the study of tourist flows within a region or between selected countries ( Zeng, 2018 ). Following previous studies, from a global perspective, this study employs this approach to investigate the roles and functions of countries/regions acting as tourism origins or destinations during the period 1995–2018, further revealing the evolution of the international tourist flow structures. The rest of this paper is structured as follows: The next section provides a brief review on tourist flow. The following section reports the data sources and methodology. Then, the results, discussion and conclusions are presented. The last section provides implications as well as future research and limitations of this paper.

2. Literature review

2.1. tourist flow.

According to Leiper (1979) , tourism system involves five elements, namely tourists, a tourist industry, original regions, transit routes and destination regions. In this regard, tourist flow refers to the movement of tourists from an origin place, through transit regions, to a destination and the stay of tourists in these regions ( Oppermann, 1995 ; Zeng, 2018 ). According to Bowden (2003) , tourist movement encompasses three basic elements: intensity, direction and pattern. Generally, the intensity is analyzed under the fields of “tourist demand” or “tourism forecasting” since it is related to the volume and frequency of tourist flows. Direction and pattern, which reflect the static and the dynamic elements of tourist flows among regions, respectively, are usually discussed under the term “tourist flow” ( Bowden, 2003 ). The dynamic element mainly centres on the flows between origin and destination regions. In contrast, the static element is composed of several factors, such as tourism destinations, overnight stays, accommodation types, and the gateways between origin and destination regions ( Oppermann, 1992 ).

A large amount of research has been conducted on tourist flow at different geographic scales ( Amelung, Nicholls, & Viner, 2007 ). The geographic scale reflects the hierarchy and functional arrangements of spatial issues, which is important for exploring tourist flow ( Bowden, 2003 ). According to Xia, Zeephongsekul, and Arrowsmith (2009) , the geographic scale of tourist flow can be attributed to the macro- and micro-levels based on distance. The macro-level refers to a relatively large distance of hundreds of kilometres ( Xia et al., 2009 ), which is often regarded as inter-destination movement pattern ( Lau & McKercher, 2006 ). In contrast, the micro-level is considered to be a relatively short distance, such as from an attraction to another attraction, which refers to intra-destination movement pattern ( Lau & McKercher, 2006 ). As far as the geographical scale of tourist flow is concerned, this study estimates the tourism flows between 221 countries/regions around the world from the macro-scale or inter-destination movement perspective.

2.2. Measurement of tourist flow patterns

The pattern of tourist flow involves various items of information, which is conducive to designing tourist packages, providing attractive combinations of attractions, proposing tourism guidance policies and marketing management ( Lew & McKercher, 2006 ; Xia et al., 2009 ). A large amount of research has attempted to map tourist flow through various methods ( Leung et al., 2011 ). The traditional techniques for tracking tourist flows mainly depend on observations, interviews or questionnaires ( Zeng, 2018 ). Researchers are asked to track the tourists' movements to develop a map of tourists' distribution within a given destination ( Dumont, Roovers, & Gulinck, 2005 ). In addition, tourists are required to retrace their movements through self-administered questionnaires ( Xia et al., 2009 ). However, limited by time and cost, these techniques usually obtain a limited amount of data and lack the needed accuracy. With the development of technology, new tracking techniques are applied to record the information of tourist flows, such as the Global Positioning System (GPS) and land-based tracking systems, which have proven to be effective tools for estimating the spatial flows of tourists over time ( Shoval & Isaacson, 2007 ).

However, the above two kinds of techniques, namely the traditional techniques and new tracking techniques, are applied to tourist flows at the micro- or meso-level. Regarding the macro-level, the panel data published by organizations are regarded as important sources for researching tourist flows ( Liu, Li, & Parkpian, 2018 ; Lozano & Gutiérrez, 2018 ; Su & Lin, 2014 ). The large amounts of data available, the use of the same statistics definitions, easy accessibility and long-term data availability, are considered as the main advantages of panel data, which contributes to the wide use of panel data in exploring international tourist flows. For example, Li, Meng, and Uysal (2008) explored the tourist flows among the Asia-Pacific countries for the years of 1995 and 2004. Based on panel data from 1990 to 2002, Keum (2010) examined the patterns of international tourist flows between South Korea and its 28 major trading partner countries.

Additionally, scholars have applied several methods, related to data mining methods and statistical methods, to identify the spatio-temporal patterns of tourist flows, including but not limited to the field of international tourist flows. These methods involve the Clustering Method ( Asakura & Iryo, 2007 ), Gross Travel Propensity Index (GTP) ( Li et al., 2008 ), Geographic Information System (GIS) Analysis ( Connell & Page, 2008 ), and Markov Chains ( Xia et al., 2009 ). For example, Asakura and Iryo (2007) applied the Clustering Method to reveal the topological characteristics of the tourist movement in Kobe, which contributes to finding the hidden behaviour of tourists. Connell and Page (2008) employed GIS analysis to map car-based tourist flows in Loch Lomond and Trossachs National Park. Xia et al. (2009) employed Markov chains to estimate the outcomes and trends of events related to the patterns of tourist flows across Phillip Island, Australia.

Recently, scholars have introduced and applied network analysis to reveal a relatively comprehensive picture of international tourist flows (e.g., Leung et al., 2011 ; Zeng, 2018 ). Compared with other statistical methods (e.g., Clustering Method), the tourist flow network based on network analysis can be visualized and is easy to understand ( Leung et al., 2011 ). Accordingly, network analysis reveals the roles, functions and cohesiveness groups of destinations, which provides more implications for destination managers ( Kang, Lee, Kim, & Park, 2018 ; Scott, Cooper, & Baggio, 2008 ).

2.3. Network analysis and international tourist flows

Mainly based on mathematics and graph theory, network analysis is an approach that uses a set of methods and tools to map and measure the patterns, flow and strength of relationships between actors ( Casanueva et al., 2014 ), which makes network analysis different from other analysis methods ( Scott et al., 2008 ). The relationships can be of various types, including but not limited to goods, services, information, and social support; the actors establishing relationships with each other can be individuals, organizations and other linked information/knowledge entities ( Haythornthwaite, 1996 ). Although the network analysis technique was mainly developed in economic sociology, researchers have applied mathematical models to estimate the structures of various relationships, indicating that network analysis was not limited to the social field ( Scott, 1991 ). Moreover, researchers like Granovetter (1973) , Burt (1992) , Watts (1999) and Lin (2001) , have furthered the research on network analysis, making it widely used in various fields.

Currently, scholars have employed network analysis to estimate the flow paths and patterns of international tourists within a destination. In these studies, a destination is regarded as an actor within the tourist flow network, while tourists from one destination to another is viewed as the relationship between destinations ( Zeng, 2018 ). For example, Leung et al. (2011) utilized network analysis to analyze the pattern of overseas tourist flows in the most visited tourist attractions throughout the Olympics in Beijing. Likewise, Zeng (2018) estimated the structure and characteristics of Chinese tourist flows in Japan through itineraries from travel services and trip diaries. Lozano and Gutiérrez (2018) explored the structure and interactions between source and destination markets in the global tourism network in 2013. Wu, Wang, and Pan (2019) combined numerical simulation and network analysis to construct an agent-based network of inbound tourism in China and numerically investigated the responses of the inbound tourist flows in some scenarios of practical significance.

However, these above-mentioned studies, mainly centring on particular regions or selected countries or specific year, hardly contribute to the understanding of the competitiveness of destination countries/regions worldwide. In this regard, the purpose of this study is to estimate the structures and evolution of international tourist flows during the period 1995 to 2018 from a global perspective, which will be further conducive to proposing general tourism development planning for most countries/regions worldwide.

3. Data and methodology

3.1. data source.

The annual data for bilateral tourist flows were collected from the UNWTO, which covers 221 countries/regions from 1995 to 2018. This data set is compiled by destination countries/regions based on the number of inbound tourists. The data for 1995 and 2018 are the earliest and latest data sets that can be obtained, respectively. Although this data set is widely used in the field of international tourism ( Balli et al., 2016 ; Yang et al., 2018 ; Zhang et al., 2017 ), three issues in the data set need to be emphasized. First, different destination countries/regions adopt different definitions in statistics. Among 8 statistics definitions currently adopted by destination countries/regions, the most commonly used statistics are arrivals of non-resident tourists at national borders (by country of residence), arrivals of non-resident tourists at national borders (by nationality), arrivals of non-resident visitors at national borders (by country of residence), and arrivals of non-resident visitors at national borders (by nationality). Following the study of Yang et al. (2018) , when cleaning the data, this study gave preference to the above definitions associated with border; 4 other definitions related to accommodation were considered when the above four border-based statistics were missing. Second, different countries/regions had different tourism statistics systems, and several countries/regions reported data for a subset of origin countries/regions. Third, this study unified the names of countries/regions to avoid the ambiguity caused by different statistical systems, such as unifying “State of Palestine” into “Palestine” and “Congo, Democratic Republic of the” into “Democratic Republic of the Congo”.

3.2. The theoretical-methodological framework of network analysis

Network analysis aims to analyze the structure of relationships (displayed by links) between given entities (displayed by actors) in social or economic phenomena ( Haythornthwaite, 1996 ). It employs a set of techniques to explore the characteristics of a whole network, as well as the roles and positions of these entities within the network ( Shih, 2006 ). In this study, we applied network analysis to explore the structure of international tourist flows, where the countries/regions are treated as “actors”, the tourist routes between origin and destination countries/regions are regarded as “links”. Fig. 1 shows a simple case with five countries/regions (labelled A, B, C, D and E) . Fig. 1 A is a network graph, showing the relationship of international tourism among these five countries/regions. For example, tourists from country/region A visit C, D and E, and do not travel to B; additionally, country/region A only receives tourists from D. According to the graph, an asymmetric matrix can be built (see Fig. 1 B), in which a row represents the destination countries/regions and a column stands for the origin countries/regions.

A simple case with five actors.

This type of matrix above merely describes the presence or absence of the given type of relationship. However, each route between two countries/regions carries a specific number of tourists, which is considered as “weightings”, yielding a valued matrix. To be specific, the ( i , j )th cell (row i , column j ) carries a number that represents the number of outbound tourists from country/region i to country/region j . On this basis, the matrix of 221 countries/regions used in this study is constructed. The rest of this section introduces the indicators of network analysis which are appropriate for this study.

To estimate the structure of international tourist flows, this study applied three indicators of network analysis, namely density, degree centrality and blockmodel. Among them, density is the main indicator for the structure of a whole network ( Casanueva et al., 2014 ), while degree centrality and blockmodel are important indicators to examine the structure of actors within a network ( Borgatti, Everett, & Johnson, 2018 ).

To be specific, density is a measure of cohesion, which means the connectedness of a network. This indicator can be interpreted as the probability of a link between each pair of randomly selected actors ( Borgatti et al., 2018 ). Degree centrality, which is measured by the number and value of links that an actor has, is suitable for analyzing the structural roles and positions of each actor within this network. However, although degree centrality is the primary indicator for the structure of an actor, it cannot contribute to understanding the importance of links between actors ( Asero, Gozzo, & Tomaselli, 2015 ). Thus, we enriched the analysis by employing the blockmodel.

The term “blockmodel” was first proposed by White, Boorman, and Breiger (1976) to explain the social structure in terms of interconnections among actors within a social network. Two actors that occupy the same structural roles or positions in a network are said to be structurally equivalent ( Asero et al., 2015 ), and are grouped into the same block. Thereby, a network is divided into different “blocks”. A “block” is a subnetwork embodied in the overall network, and the actors within a “block” are structurally indistinguishable because they have the same external relationships. This implies that the actor with the same role or position in different links can be interchangeable with one another. According to Borgatti et al. (2018) , the analysis for structural equivalence provides a high-level description of the links within a network. Moreover, structurally equivalent actors share other similarities as well; they show a certain amount of homogeneity ( Borgatti et al., 2018 ). Considering the competition in tourism market and alternative tourist flow routes, it is necessary to analyze structural equivalence when studying tourist flows ( Asero et al., 2015 ).

The formulas of these indicators have been explained by Knoke and Kuklinski (1982) , Scott (1991) , Carrington, Scott, and Wasserman (2005) , Knoke and Yang (2008) , Luo (2012) , Borgatti et al. (2018) , among others. In this regard, we explained the above indicators in the context of international tourist flow ( Table 1 ). The indicators of network analysis used in this study were calculated by UCINET 6.6.

Explanation of indicators used in this study.

Source: Knoke and Kuklinski (1982) , Scott (1991) , Carrington et al. (2005) , Knoke and Yang (2008) , Luo (2012) , Borgatti et al. (2018) .

4.1. Structure of the whole international tourist flow network

Network density indicates the extent to which countries/regions interact with other countries/regions in terms of international tourism. Fig. 2 shows the network density of international tourist flows among 221 countries/regions for each year from 1995 to 2018. On the whole, the international tourist flow network was a sparse network with low density. The network density significantly increased, with the value of 2018 (0.0299) being more than twice that of 1995 (0.0108), which demonstrates the increasing travel connections among countries/regions. As seen from Fig. 2 , the increasing trend in density can be divided into five phases: periods of rapid growth from 1995 to 2000, from 2003 to 2007, and from 2009 to 2018, and periods of fluctuation from 2000 to 2003 and from 2007 to 2009. The period of fluctuation in density coincides with the period of major crisis events, such as the 9/11 terrorist attacks in 2001, the severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS) in 2003 and the financial crisis in 2008. Additionally, the trend of density was essentially consistent with that of international tourist arrivals as listed in Fig. 2 . After 2009, the number of international tourists and the network density of international tourist flows continued to increase significantly.

The number of international tourists and the density of the international tourist flow network from 1995 to 2018.

Moreover, Gephi software was applied to visualize the distribution of international tourist flows. Fig. 3 and Fig. 4 show the international tourist flow networks in 1995 and 2018, respectively. The larger node size indicates that a particular country/region generate more international tourists, while the thicker line between countries/regions represents more outbound tourists. As shown in Fig. 3 , in 1995, the largest cluster for the international tourist flow network was Europe, followed by North America and East Asia, with several countries as the centre, including the United States, Germany, Canada, France, and the United Kingdom. A large number of countries/regions were at the edge of the international tourist network and had only a few travel links with the remaining countries/regions within this network in 1995. While in 2018, we can find that after 24 years, almost all countries/regions have strengthened travel links with other countries/regions, which suggests that the interconnectedness of the international tourist flow network has been largely improved. Although Europe, North America and East Asia were still the most important clusters, the number of countries/regions covered in these clusters had increased significantly.

The global tourist flow network in 1995.

The global tourist flow network in 2018.

4.2. Structure of countries/regions within the international tourist flow network

4.2.1. the roles and functions of countries/regions in outbound tourism.

Out-degree centrality was used to describe the role and function of a country/region in outbound tourism. The results of the out-degree centrality are summarized in Fig. 5 . During the study period, out-degree centrality values of most countries/regions were on the rise, with occasional fluctuations in 2001, 2003 or 2008, and maintained a relatively stable ranking. Thus, Table 2 only reports the values of out-degree centrality and rankings of countries/regions in 2018 because of space limitations.

Result of the out-degree centrality for 221 countries/regions from 1995 to 2018.

The centrality analysis of countries/regions in the international tourist flows in 2018.

Given that countries/regions in the top 30 account for about 80% of the sum of out-degree centrality in the 221 countries/regions, we considered these countries/regions occupied a relatively important role and function in outbound tourism. Over the 24 years, Germany, the United Kingdom, France, Switzerland, Czech Republic, Italy, Belgium, Austria, Spain, the Netherlands, Ukraine, the Russian Federation, the United States, Canada, Mexico, China, Hong Kong SAR, Macao SAR, Taiwan, Japan and Australia were always in the top 30, playing a dominant role in generating international tourists to many destination countries/regions. In particular, among these 21 countries/regions, 12 of them, including Germany and the United Kingdom, belong to Europe; the United States, Canada and Mexico are countries in North America; China, Japan, Hong Kong SAR, Macao SAR, Taiwan are located in East Asia; and Australia belongs to Oceania.

Specifically, during the period 1995–2018, Germany always ranked 1st, with an average out-degree centrality value of 107.444, indicating that Germany plays a leading role in global outbound tourism, taking into account the number of destination countries/regions and outbound tourists. In particular, before 2000, the out-degree centrality values of Germany were far higher than those of the United States, which ranked 2nd. The out-degree centrality values of the United States showed a relatively stable upward trend from 1995 to 2013 and a sharp increase after 2013. During 2002 and 2015, the out-degree centrality values of Hong Kong SAR surpassed those of the United States, ranking 2nd in the international tourist flow network, and maintained a slight upward trend after 2007. France, Canada and Italy maintained a relatively stable ability to interact with other destination countries/regions and showed a steady growth trend throughout this study period.

Regarding the Russian Federation, its out-degree centrality value showed an increasing trend until 2013, after which it began to decrease sharply. This may be related to the sharp decline of oil price, the Ukraine crisis in 2014 and the sanctions imposed by Western countries, which make the economy stagnant in the Russian Federation and further have a negative impact on tourism ( Dreger, Kholodilin, Ulbricht, & Fidrmuc, 2016 ). It is worth noting that the out-degree centrality value of China continued to significantly increase from 1995 (4.836 of out-degree centrality) to 2018 (113.394 of out-degree centrality), with only a slight decrease in 2008 due to the financial crisis; moreover, the ranking of China showed an upward trend from 21st in 1995 to 3rd in 2018. Besides, after the financial crisis in 2008, the growth of out-degree centrality of most countries/regions slowed, while China showed a trend of unprecedented growth to generate outbound tourists to increasing destination countries/regions.

4.2.2. The roles and functions of countries/regions in inbound tourism

In-degree centrality was used to describe the role and function of a country/region in the inbound tourism network. As shown in Fig. 6 , in-degree centrality values significantly varied in 221 countries/regions between 1995 and 2018. As a whole, the in-degree centrality values of most countries/regions fluctuated upward and maintained relatively stable rankings. Similar to out-degree centrality, the fluctuations in the vast majority of countries/regions occurred in 2001, 2003 or 2008. From 1995 to 2018, Poland, Italy, France, the United Kingdom, Spain, Austria, Germany, the Russian Federation, Turkey, Greece, Netherlands, the United States, Mexico, Canada, China, Hong Kong SAR, Macao SAR, Singapore and Thailand remained in the top 30, with a strong aggregation function for international tourist flows around the globe. Generally, countries/regions in Europe, East Asia, Southeast Asia and North America ranked in the top. Besides, Latin America ranked in the middle, and Africa and Oceania, with several exceptions (e.g., South Africa, Egypt, Australia, New Zealand), had low in-degree centrality values out of the 221 countries/regions over 24 years.

Result of the in-degree centrality for 221 countries/regions from 1995 to 2018.

Specifically, the in-degree centrality values of China had extremely significant growth, and China surpassed Poland to become the leading tourist destination in the international tourist flow network in 2000. Moreover, China, which reached 158.449 of in-degree centrality in 2018 ( Table 2 ), maintained or increased most connections with other origin countries/regions and had the strongest ability to attract international tourists compared with the rest of the world. Concerning other leading destination countries/regions, the in-degree centrality values and rankings of Spain, the United States, Italy, France and Poland have remained close to each other since 2001, and ahead of other countries/regions, including the United Kingdom, which has almost always ranked around 7th out of 221 countries/regions since 1997. As the most important inbound tourism destination in the last century, Poland's in-degree centrality values fell sharply between 1999 (89.070 of in-degree centrality) and 2002 (50.691 of in-degree centrality), and between 2007 (66.085 of in-degree centrality) and 2009 (53.597 of in-degree centrality). The United States showed a similar trend to Poland in terms of in-degree centrality, but more smoothly during the study period. It is worth noting that Southeast Asian countries, such as Thailand, Malaysia, Singapore, Vietnam and Indonesia, were at the forefront of the inbound tourist flow network, consistent with the national positioning created by these countries. Moreover, countries/regions with regional conflicts or infectious diseases had low in-degree centrality values, such as Sudan, Chad, Palestine and the Central African Republic. Tourists throughout the world rarely visit these countries/regions considering their safety.

Furthermore, the rankings of out-degree centrality of countries/regions were relatively consistent with those of their in-degree centrality within the international tourist flow network. For example, countries/regions with high out-degree centrality tended to have high in-degree centrality in the international tourist flow network, including but not limited to Germany, the United States, China, the United Kingdom, France, Japan, Canada, Hong Kong SAR, Italy, Spain, Macao SAR and the Russian Federation, which are concentrated in Europe, East Asia and North America. Moreover, the out-degree centrality in countries/regions with small in-degree centrality also tended to be small, such as Sierra Leone, Montserrat, and Seychelles ( Table 2 ). Most of the countries/regions mentioned above are located in Africa or are islands with small populations and territories. However, the majority of countries in Southeast Asia, including Thailand, Indonesia and Malaysia, had higher rankings in in-degree centrality than that of out-degree centrality during the years of the study, revealing that inbound tourism was a significant pillar of the growth strategies of these countries. Besides, except for countries/regions (e.g., French Guiana, Pakistan, Iraq) that did not have statistics on inbound tourist arrivals, the values of out-degree centrality in several countries/regions (e.g., Republic of Moldova, Belarus, Belgium) were higher than those of in-degree centrality, indicating that these countries/regions have a stronger ability to generate international tourists to many countries/regions than to attract tourists.

4.2.3. The substitutability of countries/regions

The above subsections mainly reveal the role and function of a country/region in the international tourist flow network and do not allow for the importance of travel links between countries/regions to be understood. Therefore, following the study of Asero et al. (2015) , this study used the CONCOR algorithm to estimate the structure corresponding to the country/region's role and position in the network. Countries/regions with the same tourist flow routes can be clustered into one block, indicating that countries/regions in the same block are structurally equivalent and can be substituted for each other ( Luo, 2012 ). Also, CONCOR algorithm provides the density of each of the blocks ( Borgatti et al., 2018 ), and allows for identifying the main links from the values of the density matrix ( Asero et al., 2015 ). Since the roles and positions of countries/regions in the international tourist flow network are relatively stable, countries/regions in each block have not changed significantly over the years. Therefore, we took the results of the 2018 CONCOR algorithm as an example ( Table 3 and Table 4 ).

Members of each block for 2018.

Density within and between blocks for 2018.

Block 1 centred on the Russian Federation and Belarus, and mainly included countries/regions distributed around the Caspian Sea (e.g., Turkmenistan, Kazakhstan, Islamic Republic of Iran). The majority of countries/regions within this block had a higher value of out-degree centrality than that of in-degree centrality, especially Belarus and Republic of Moldova. Moreover, as shown in Table 4 , countries/regions in Block 1 were closely linked to each other (Density = 0.179) and interacted with countries/regions in other blocks except for Block 3. This suggests that most countries/regions within Block 1 have a strong ability to generate international tourists to both countries/regions in other blocks and its own block. The majority of countries/regions in Block 2 are concentrated in North and Central Africa (e.g., Algeria, Sudan, Djibouti) and Arabian Peninsula (e.g., Saudi Arabia, Kuwait, Yemen); that is, around the Red Sea. Except for Saudi Arabia, the degree centrality of countries/regions within this block generally ranked in the middle or lower among 221 countries/regions, indicating that these countries/regions have a medium performance in international tourism.

As for Block 3, except for French Guiana and Guadeloupe, which are French overseas regions, other 16 countries, including Burundi and Mozambique, mainly belong to Central or Southern Africa. Most countries/regions in this block had low values of degree centrality and barely had travel links with other countries/regions, suggesting that these countries/regions are at the edge of international tourism flow network. According to Block 4, except for Suriname, 23 countries/regions in this block are around the Central or Western Pacific (e.g., China, Malaysia, Indonesia), and the remaining countries/regions are located around the Gulf of Guinea (e.g., Côte d'Ivoire, Liberia). Asian countries/regions in Block 4 generally ranked higher than those in Africa and Oceania in terms of degree centrality. Besides, the interactions between countries/regions within this block (Density = 0.252) were much higher than those with countries/regions in other blocks.

Countries in Block 5 are located in Europe, such as Greece, the United Kingdom, Ukraine, Belgium, Germany and France. Generally, European countries have small territories, developed economies and high affluence rankings in the world. These countries not only generate international tourists but also have the ability to attract tourists from other countries/regions. Besides, its block density was the highest, reaching 0.328, revealing the close connections between European countries. In Block 6, countries/regions are mainly distributed along the Mediterranean Sea (e.g., Tunisia, Morocco, Egypt, Malta, Spain) and the West or North Indian Ocean (e.g., Seychelles, Madagascar, Maldives, Sri Lanka), while a few countries/regions are concentrated in the Gulf of Guinea (e.g., Togo, Congo). The majority of countries/regions in Block 6 had higher rankings in in-degree centrality than that of out-degree centrality, indicating that these countries/regions have a stronger ability to attract international tourists.

Block 7 was dominated by the United States, Canada, and Mexico. Except for the above three countries, other 35 American countries/regions within this block possessed medium or small degree centrality, such as Cayman Islands, Aruba, Colombia. Other countries/regions in Block 7 are located in Asia (e.g., Qatar, Armenia, Israel, Philippines, Nepal), Africa (e.g., United Republic of Tanzania, Ethiopia), Oceania (e.g., Kiribati, French Polynesia) and Europe (i.e., Iceland). Countries/regions within this block has established travel links with countries/regions in the other seven blocks, especially with European countries in Block 5. Block 8 focused on countries/regions located in South America (e.g., Argentina, Brazil, Venezuela, Bolivia), and islands located in Oceania or Western Pacific, including but not limited to Australia, New Zealand, Japan, Cook Islands, Fiji, and Palau. As shown in Table 4 , countries/regions within Block 8 mainly interacted with other countries/regions in its block as well as Block 7 and Block 5.

From the above analysis, countries/regions within the same block are mostly located on the same continent or are geographically close to each other. Geographic contiguity, language similarity or colonial links between two countries/regions increase the bilateral flow of tourists ( Yang et al., 2018 ). It is worth noting that countries/regions located in a block have the same external tourist flows, and the substitution effect refers to the structurally equivalent relationship between countries/regions. In the real situation, every country/region has uniqueness attributes in nature, culture and other aspects that cannot be replicated by other countries/regions within the same block.

5. Discussion and conclusions

Recent years have seen the rapid development of international tourism. The number of international tourists and the amount of tourism revenues are measures of international tourism from the quantity point of view (e.g., Su & Lin, 2014 ; Balli et al., 2016 ; Liu, Li, and Parkpian, 2018 ); however, the network structure and evolution of international tourist flows lack attention. Essentially, international tourism involves cross-border activities ( Deng & Hu, 2018 ). Given the move toward globalization, the order of international tourism is constantly changing ( Yang et al., 2018 ) and can be revealed by the movement of international tourists. Identifying the structure and evolution of international tourist flows is critical for understanding the changes in the past and for formulating effective strategies for future tourism development ( Lew & McKercher, 2006 ). In this regard, based on network analysis, this study empirically evaluates the evolution of international tourist flows between 221 countries/regions during the period 1995–2018 from the perspective of structure, rather than tourist arrivals or tourism revenues.

Network analysis is an approach used to map and measure the flow paths of resources between actors within a network system ( Zha, Shao, & Li, 2019 ), which is suitable for exploring the movement of international tourists. Currently, scholars have applied this approach to the study of tourist flows ( Zeng, 2018 ). However, studies have been limited to a specific region, such as China ( Leung et al., 2011 ) and Sicily ( Asero et al., 2015 ), and lack a global perspective with few exceptions (e.g., Lozano & Gutiérrez, 2018 ). Moreover, these studies mainly centre on a specific year (e.g., Lozano & Gutiérrez, 2018 ; Zeng, 2018 ). Great changes have taken place and are ongoing in the world order since the last century, which has also had a profound impact on international tourism ( Yang et al., 2018 ). Thus, this study applies network analysis to explore the roles, functions and evolutions of countries/regions over the world in tourism flow networks, thereby enriching the study of tourist flows from a global perspective. Understanding the structure and evolution of international tourist flows can be useful for improving market competitiveness and destination management.

This study constructs the international tourist flow network and attempts to reveal the structure and evolution of this network from two levels: the whole network and actor. As for the whole network, the estimated results of the density indicator show that the international tourist flow network is a sparse network, but its density is on the rise. This is related to globalization ( Keum, 2010 ) and government policies ( Deng & Hu, 2018 ), among other factors. This finding echoes the conclusion in the study of Friedman (2005) that the world is flat. Moreover, according to Var, Schlüter, Ankomah and Lee (1989) and Becken and Carmignani (2016) , globalization promotes international tourism around the world, whereas international tourism contributes to globalization, making tourism a real force for world peace.

Moreover, there are fluctuations in the growth in the network density, especially for years 2000 to 2003 and 2007 to 2009, which can be attributed to crisis events, including the September 11 attacks in 2001 and their aftermath ( Dragouni, Filis, Gavriilidis, & Santamaria, 2016 ), SARS in 2003 ( Ritchie, 2008 ), the financial crisis in 2008 ( Hall, 2010 ), the influenza A (H1N1) epidemic in 2009 ( Lee, Song, Bendle, Kim, & Han, 2012 ), and other factors. It should be noted that the studied period has seen several crisis events, including but not limited to the above-mentioned ones. However, only global crises, especially global public health crises, have an impact on the structure of the international tourist flow network. In this regard, we can forecast that the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19), which continues to spread rapidly across the world, has led to a decline in the network density of international tourism flows.

In terms of the actor, the role and function of a country/region in the international tourist flow network are identified utilizing the degree centrality indicator. The roles and functions of countries/regions within the outbound tourist network are a reflection of a country's economic development ( Li et al., 2008 ), the level of openness ( Liu, Li, & Li, 2018 ), price competitiveness index ( Seetaram, Forsyth, & Dwyer, 2016 ), government policy ( Li, Harrill, Uysal, Burnett, & Zhan, 2010 ) and population ( Li, Shu, Tan, Huang, & Zha, 2019 ), while those of the inbound tourist flow network are related to tourism competitiveness ( Mou et al., 2020 ), tourist attractions ( Su & Lin, 2014 ) and culture ( Yang & Wong, 2012 ), among others.

Specifically, among these 221 countries/regions, Germany, Italy, the United Kingdom, France, Spain, Austria, the Russian Federation, the United States, Canada, Mexico, China, Hong Kong SAR and Macao SAR are among the top tourist-generating and receiving countries/regions from 1995 to 2018 and are regarded as the core actors within the international tourist flow network. This finding is consistent with the study of Lozano and Gutiérrez (2018) . These 13 countries/regions are concentrated in Europe, East Asia and North America, with vast territories (e.g., the Russian Federation, Canada, the United States), developed economies (e.g., Germany, the United States, France), relative political stability (e.g., Germany, China, the United Kingdom) or large populations (e.g., China, Mexico, the United States) on the whole ( Li et al., 2008 ).

Germany, in particular, plays a leading role in the global outbound tourism market from 1995 to 2018, while China has acted as the dominating inbound tourism market since 2000 when considering the number of destination/origin countries/regions and international tourists. The Henley & Partners Visa Restriction Index shows that German passports are among one of the most valuable passports worldwide. For example, German passport holders can visit 176 countries worldwide visa-free in 2017 ( Henley & Partners, 2017 ). According to Wu et al. (2019) , China gave priority to inbound tourism from 1949 to 2008 for both political and economic reasons. Recently, China has developed government policies concerning tourism, such as the Belt and Road Initiative, largely enhancing the inbound tourism market and even changing China's inbound tourism market landscape ( Huang et al., 2019 ). Moreover, other factors, including China's thriving history and culture ( Lim & Pan, 2005 ), cannot be ignored.

Countries/regions that do not perform well within the international tourist flow network over the years are mainly located in Africa or on islands, such as Montserrat and Niue, with performances affected by safety concerns, transportation accessibility or small populations. This finding echoes the study of Li et al. (2008) . Besides, the majority of countries in Southeast Asia (e.g., Thailand and Malaysia) have relatively well-developed inbound tourism compared with outbound tourism due to the availability of abundant tourism resources, government support (e.g., the proposal of the Malaysia Tourism Transformation Plan) ( Liu et al., 2018 ), a vast diversity of tourism products ( Liu et al., 2018 ) and a relatively low exchange rate ( Seetaram et al., 2016 ). Moreover, a small majority of countries/regions, such as the Republic of Moldova, Belarus and Sweden, play relatively more important roles and functions in outbound tourism than inbound tourism over the years.

Regarding the structure corresponding to the country/region's role or position in the network, the CONCOR algorithm estimates the structurally equivalent countries/regions of the international tourist flow network flows in 2018. Most countries/regions with similar or the same external links in terms of international tourism are located on the same continent or are geographically close. This finding is in line with the study of Lozano and Gutiérrez (2018) that the clustered structure is determined by geographical factors. Geographically close countries/regions have similar natural, cultural and political environments, which can affect the tourism industry ( Yang et al., 2018 ). For example, Narayan, Narayan, Prasad, and Prasad (2010) noted that Pacific Island countries, especially Fiji, the Solomon Islands and Papua New Guinea (in Block 8 of this study), have similar natural disasters and political instability, which can influence the choices of international tourists. Given the fierce competition in the international tourism market, countries/regions that are structurally equivalent need to provide different kinds of leisure products to be differentiated to international tourists.

6. Implications, limitations and further research

The policy implications are clear and of great significance. First, policymakers should analyze international tourist flows not only from the perspective of tourist arrivals and tourism revenues but also from the perspective of network structure. Future policies should be proposed, such as establishing partnerships with more countries/regions, to address the problems related to tourism in the increasingly globalized world. Second, policymakers should manage tourism routes, plan tourism facilities and define marketing strategies by identifying the roles and functions of countries/regions within the international tourist flow network. Third, according to the results of this study, countries/regions that are geographically close have similar or the same international tourist flow structures. Thus, differentiated tourism products should be provided to create a unique and competitive tourism image for a country/region.

It is important to note that this study has several limitations. First, the data used in this study is compiled by destination countries/regions, each of which may adopt distinct definitions of tourism and may collect tourist arrival data differently. Currently, there are 8 statistics definitions related to national borders or accommodation establishments, which may affect the accuracy of the data set used in this study. Second, due to the use of different tourism statistics systems, several countries/regions only reported data for a subset of origin countries/regions, leading to missing values in the data set. Third, limited by the research goal, it is difficult to analyze every country/region in the world, which may ignore some important evaluations of individual countries/regions.

Implications for future research involve a more in-depth exploration of the international tourist flow network. According to Welch, Welch, Young, and Wilkinson (1998) , as actors define various elements of the network and interact with the external environment, relationships between actors are constantly shifting. In other words, networks are dynamic, and links between countries/regions are both built and lost. Future research is needed to examine the factors (e.g., visa, air transportation) that affect the structure, and how the structure influences the socio-economic development of a country/region. Second, it is an exciting research endeavour to apply network analysis to establish relationships among different agents related to international tourism (e.g., air carriers, tourism service providers in destination). Third, considering the impact of crises on the tourism system, future research should focus on the impact of global crisis events (e.g., COVID-19) on the structure of international tourism (e.g., redistributing power and other resources in the network), and recovery measures.

Declaration of Competing Interest

Acknowledgements.

This study was supported by a grant from the National Social Science Fund of China (17XGL012).

Biographies

Yuhong Shao is a doctoral candidate in the School of Tourism, Sichuan University, P.R. China. Her research interests include outbound tourism, tourism employment and tourism economics.

Songshan (Sam) Huang is Professor of Tourism and Services Marketing in the School of Business and Law, Edith Cowan University, Australia. His research interests include Chinese tourist behaviours, destination marketing, tour guiding and various aspects of China tourism issues.

Yingying Wang is a master student in the School of Tourism, Sichuan University, P.R. China. Her research interests include outbound tourism, tourism education and hospitality management.

Zhiyong Li is a professor as well as the Dean of School of Tourism, Sichuan University, P.R. China. His research interests center on tourism marketing, outbound tourism and hospitality management.

Mingzhi Luo is a lecturer in the School of Tourism, Sichuan University, P.R. China. His research interest includes tourism economics and tourism policy. He is currently working on tourism recovery affected by natural disasters.

- Amelung B., Nicholls S., Viner D. Implications of global climate change for tourism flows and seasonality. Journal of Travel Research. 2007; 45 (3):285–296. doi: 10.1177/0047287506295937. [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Asakura Y., Iryo T. Analysis of tourist behaviour based on the tracking data collected using a mobile communication instrument. Transportation Research Part A: Policy and Practice. 2007; 41 (7):684–690. doi: 10.1016/j.tra.2006.07.003. [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Asero V., Gozzo S., Tomaselli V. Building tourism networks through tourist mobility. Journal of Travel Research. 2015; 55 (6):751–763. doi: 10.1177/0047287515569777. [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Balli F., Balli H.O., Louis R.J. The impacts of immigrants and institutions on bilateral tourism flows. Tourism Management. 2016; 52 :221–229. doi: 10.1016/j.tourman.2015.06.021. [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Becken S., Carmignani F. Does tourism lead to peace? Annals of Tourism Research. 2016; 61 (11):63–79. doi: 10.1016/j.annals.2016.09.002. [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Borgatti S.P., Everett M.G., Johnson J.C. Sage; London: 2018. Analyzing social networks. [ Google Scholar ]

- Bowden J. A cross-national analysis of international tourist flows in China. Tourism Geographies. 2003; 5 (3):257–279. doi: 10.1080/14616680309711. [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Burt R. Harvard University Press; Cambridge, MA: 1992. Structural holes: The social structure of competition. [ Google Scholar ]

- Carrington P.J., Scott J., Wasserman S. Cambridge University Press; Cambridge: 2005. Models and methods in social network analysis. [ Google Scholar ]

- Casanueva C., Gallego Á., García-Sánchez M.R. Social network analysis in tourism. Current Issues in Tourism. 2014; 19 (12):1190–1209. doi: 10.1080/13683500.2014.990422. [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Connell J., Page S.J. Exploring the spatial patterns of car-based tourist travel in Loch Lomond and Trossachs National Park, Scotland. Tourism Management. 2008; 29 (3):561–580. doi: 10.1016/j.tourman.2007.03.019. [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Deng T.T., Hu Y.K. Modelling China’s outbound tourist flow to the “Silk Road”: A spatial econometric approach. Tourism Economics. 2018; 25 (8):1167–1181. doi: 10.1177/1354816618809763. [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Dragouni M., Filis G., Gavriilidis K., Santamaria D. Sentiment, mood and outbound tourism demand. Annals of Tourism Research. 2016; 60 (9):80–96. doi: 10.1016/j.annals.2016.06.004. [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Dreger C., Kholodilin K.A., Ulbricht D., Fidrmuc J. Between the hammer and the anvil: The impact of economic sanctions and oil prices on Russia’s ruble. Journal of Comparative Economics. 2016; 44 (2):295–308. doi: 10.1016/j.jce.2015.12.010. [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Dumont B., Roovers P., Gulinck H. Estimation of off-track visits in a nature reserve: A case study in Central Belgium. Landscape and Urban Planning. 2005; 71 (2–4):311–321. doi: 10.1016/s0169-2046(04)00084-2. [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Friedman T.L. Farrar, Straus and Giroux; New York: 2005. The world is flat: A brief history of the twenty-first century. [ Google Scholar ]

- Granovetter M.S. The strength of weak ties. American Journal of Sociology. 1973; 78 (6):1360–1380. doi: 10.1086/225469. [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Hall C.M. Crisis events in tourism: Subjects of crisis in tourism. Current Issues in Tourism. 2010; 13 (5):401–417. doi: 10.1080/13683500.2010.491900. [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Haythornthwaite C. An approach and technique for the study of information exchange. Library & Information Science Research Social network analysis. 1996; 18 (4):323–342. doi: 10.1016/s0740-8188(96)90003-1. [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Henley & Partners Henley & Partners Passport Index. 2017. https://www.henleyglobal.com/henley-passport-index/ (Accessed 5 November 2019)

- Huang X., Han Y., Gong X., Liu X. Does the belt and road initiative stimulate China's inbound tourist market? An empirical study using the gravity model with a DID method. Tourism Economics. 2019; 26 (2):299–323. doi: 10.1177/1354816619867577. [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Kang S., Lee G., Kim J., Park D. Identifying the spatial structure of the tourist attraction system in South Korea using GIS and network analysis: An application of anchor-point theory. Journal of Destination Marketing & Management. 2018; 9 :358–370. doi: 10.1016/j.jdmm.2018.04.001. [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Keum K. Tourism flows and trade theory: A panel data analysis with the gravity model. The Annals of Regional Science. 2010; 44 (3):541–557. doi: 10.1007/s00168-008-0275-2. [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Knoke D., Kuklinski J.H. Sage; Beverly Hills: 1982. Network analysis. [ Google Scholar ]

- Knoke D., Yang S. 2nd ed. Sage; Thousand Oaks, CA: 2008. Social network analysis. [ Google Scholar ]

- Lau G., McKercher B. Understanding tourist movement patterns in a destination: A GIS approach. Tourism and Hospitality Research. 2006; 7 (1):39–49. doi: 10.1057/palgrave.thr.6050027. [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Lee C.K., Song H.J., Bendle L.J., Kim M.J., Han H. The impact of non-pharmaceutical interventions for 2009 H1N1 influenza on travel intentions: A model of goal-directed behavior. Tourism Management. 2012; 33 (1):89–99. doi: 10.1016/j.tourman.2011.02.006. [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Leiper N. The framework of tourism. Annals of Tourism Research. 1979; 6 (4):390–407. doi: 10.1016/0160-7383(79)90003-3. [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Leung X.Y., Wang F., Wu B.H., Bai B., Stahura K.A., Xie Z.H. A social network analysis of overseas tourist movement patterns in Beijing: The impact of the Olympic Games. International Journal of Tourism Research. 2011; 14 (5):469–484. doi: 10.1002/jtr876. [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Lew A., McKercher B. Modeling tourist movements. Annals of Tourism Research. 2006; 33 (2):403–423. doi: 10.1016/j.annals.2005.12.002. [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Li X., Harrill R., Uysal M., Burnett T., Zhan X. Estimating the size of the Chinese outbound travel market: A demand-side approach. Tourism Management. 2010; 31 (2):250–259. doi: 10.1016/j.tourman.2009.03.001. [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Li X., Meng F., Uysal M. Spatial pattern of tourist flows among the Asia-Pacific countries: An examination over a decade. Asia Pacific Journal of Tourism Research. 2008; 13 (3):229–243. doi: 10.1080/10941660802280323. [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Li Z., Shu H., Tan T., Huang S., Zha J. Does the demographic structure affect outbound tourism demand? A panel smooth transition regression approach. Journal of Travel Research. 2019; 59 (5):893–908. doi: 10.1177/00472875198671. [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Lim C., Pan G.W. Inbound tourism developments and patterns in China. Mathematics and Computers in Simulation. 2005; 68 (5–6):498–506. doi: 10.1016/j.matcom.2005.02.004. [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Lin N. Cambridge University Press; Cambridge: 2001. Social forces social capital: A theory of social structure and action. [ Google Scholar ]

- Liu Y.P., Li Y.C., Li L. A panel data-based analysis of factors influencing market demand for Chinese outbound tourism. Asia Pacific Journal of Tourism Research. 2018; 23 (7):667–676. doi: 10.1080/10941665.2018.1486863. [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Liu Y.P., Li Y.C., Parkpian P. Inbound tourism in Thailand: Market form and scale differentiation in ASEAN source countries. Tourism Management. 2018; 64 (4):22–36. doi: 10.1016/j.tourman.2017.07.016. [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Lozano S., Gutiérrez E. A complex network analysis of global tourism flows. International Journal of Tourism Research. 2018; 20 :588–604. doi: 10.1002/jtr.2208. [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Luo J.D. 2nd ed. Social Sciences Academic Press; Beijing: 2012. Social network analysis. [ Google Scholar ]

- Mou N.X., Yuan R.Z., Yang T.F., Zhang H.C., Tang J.W., Makkonen T. Exploring spatio-temporal changes of city inbound tourism flow: The case of Shanghai, China. Tourism Management. 2020; 76 (1):1–14. doi: 10.1016/j.tourman.2019.103955. [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Narayan P.K., Narayan S., Prasad A., Prasad B.C. Tourism and economic growth: A panel data analysis for pacific island countries. Tourism Economics. 2010; 16 (1):169–183. doi: 10.5367/000000010790872006. [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Oppermann A model of travel itineraries. Journal of Travel Research. 1995; 34 (4):57–61. doi: 10.1177/004728759503300409. [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Oppermann M. Intranational tourist flows in Malaysia. Annals of Tourism Research. 1992; 19 (3):482–500. doi: 10.1016/0160-7383(92)90132-9. [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Ritchie B. Tourism disaster planning and management: From response and recovery to reduction and readiness. Current Issues in Tourism. 2008; 11 (4):315–348. doi: 10.1080/13683500802140372. [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Scott J. Sage; London: 1991. Social network analysis. A handbook. [ Google Scholar ]

- Scott N., Cooper C., Baggio R. Destination networks. Annals of Tourism Research. 2008; 35 (1):169–188. doi: 10.1016/j.annals.2007.07.004. [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Seetaram N., Forsyth P., Dwyer L. Measuring price elasticities of demand for outbound tourism using competitiveness indices. Annals of Tourism Research. 2016; 56 (1):65–79. doi: 10.1016/j.annals.2015.10.004. [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Shih H.Y. Network characteristics of drive tourism destinations: An application of network analysis in tourism. Tourism Management. 2006; 27 (5):1029–1039. doi: 10.1016/j.tourman.2005.08.002. [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Shoval N., Isaacson M. Tracking tourists in the digital age. Annals of Tourism Research. 2007; 34 (1):141–159. doi: 10.1016/j.annals.2006.07.007. [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Su Y.W., Lin H.L. Analysis of international tourist arrivals worldwide: The role of world heritage sites. Tourism Management. 2014; 40 :46–58. doi: 10.1016/j.tourman.2013.04.005. [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Var T., Schliiter R., Ankomah P., Lee T. Tourism and world peace: The case of Argentina. Annals of Tourism Research. 1989; 16 (3):431–434. doi: 10.1016/0160-7383(89)90055-8. [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Watts D.J. Princeton University Press; Princeton: 1999. Small worlds: The dynamics of networks between order and randomness. [ Google Scholar ]

- Welch D., Welch L., Young L., Wilkinson I. The importance of networks in export promotion: Policy issues. Journal of International Marketing. 1998; 6 (4):66–82. doi: 10.1177/1069031x9800600405. [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- White H.C., Boorman S.A., Breiger R.L. Social structure from multiple networks. I. Blockmodels of roles and positions. American Journal of Sociology. 1976; 81 (4):730–780. doi: 10.1086/226141. [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- World Tourism Organization . 2019. International tourism highlights, 2019 Edition. (Accessed 6 November 2019) [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- World Tourism Organization International tourism, receipts (current US$) 2020. https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/ST.INT.RCPT.CD/ (Accessed 6 August 2020)

- Wu J.F., Wang X.G., Pan B. Agent-based simulations of China inbound tourism network. Scientific Reports. 2019; 9 (1):1–17. doi: 10.1038/s41598-019-48668-2. [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Xia J., Zeephongsekul P., Arrowsmith C. Modelling spatio-temporal movement of tourists using finite Markov chains. Mathematics and Computers in Simulation. 2009; 79 (5):1544–1553. doi: 10.1016/j.matcom.2008.06.007. [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Yang Y., Liu H., Li X. The world is flatter? Examining the relationship between cultural distance and international tourist flows. Journal of Travel Research. 2018; 58 (2):224–240. doi: 10.1177/0047287517748780. [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Yang Y., Wong K.K.F. The influence of cultural distance on China inbound tourism flows: A panel data gravity model approach. Asian Geographer. 2012; 29 (1):21–37. doi: 10.1080/10225706.2012.662314. [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Zeng B. Pattern of Chinese tourist flows in Japan: A social network analysis perspective. Tourism Geographies. 2018; 20 (5):810–832. doi: 10.1080/14616688.2018.1496470. [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Zha J.P., Shao Y.H., Li Z.Y. Linkage analysis of tourism-related sectors in China: An assessment based on network analysis technique. International Journal of Tourism Research. 2019; 21 (4):531–543. doi: 10.1002/jtr.2280. [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Zhang Y., Li X., Wu T. The impacts of cultural values on bilateral international tourist flows: A panel data gravity model. Current Issues in Tourism. 2017; 22 (8):967–981. doi: 10.1080/13683500.2017.134587. [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

Travel, Tourism & Hospitality

Travel and tourism in the U.S. - statistics & facts

What are the most popular travel destinations in the u.s., u.s. travel trends, key insights.

Detailed statistics

Tourism contribution to GDP in the U.S. 2019-2022

Total travel expenditures in the U.S. 2019-2026

Number of domestic leisure and business trips in the U.S. 2019-2026

Editor’s Picks Current statistics on this topic

Current statistics on this topic.

International travel spending in the U.S. 2019-2026

Leading city destinations in the U.S. 2019, by number of international arrivals

Related topics

Recommended.

- National park tourism in the U.S.

- Millennial travel behavior in the U.S.

- Tourism worldwide

- Hotel industry worldwide

- Sustainable tourism worldwide

Recommended statistics

Industry overview.

- Basic Statistic Tourism contribution to GDP in the U.S. 2019-2022

- Premium Statistic Total travel expenditures in the U.S. 2019-2026

- Premium Statistic Direct travel spending in the U.S. 2019-2022, by traveler type

- Basic Statistic Countries that visited the U.S. the most 2019-2022

- Basic Statistic Leading outbound travel markets in the U.S. 2019-2022, country

- Basic Statistic Contribution of travel and tourism to employment in the U.S. 2019-2022

- Premium Statistic Most visited states in the U.S. 2022

Total contribution of travel and tourism to the gross domestic product (GDP) in the United States in 2019 and 2022 (in trillion U.S. dollars)

Total travel spending in the United States from 2019 to 2022, with a forecast until 2026 (in trillion U.S. dollars)

Direct travel spending in the U.S. 2019-2022, by traveler type

Total direct travel spending in the United States from 2019 to 2022, by type of traveler (in billion U.S. dollars)

Countries that visited the U.S. the most 2019-2022

Distribution of international tourist arrivals in the United States in 2019 and 2022, by country

Leading outbound travel markets in the U.S. 2019-2022, country

Distribution of outbound tourist departures in the United States in 2019 and 2022, by country

Contribution of travel and tourism to employment in the U.S. 2019-2022

Contribution of travel and tourism to employment in the United States in 2019 and 2022 (in millions)

Most visited states in the U.S. 2022

Most visited states by adults in the United States as of September 2022

Key players

- Premium Statistic Leading holiday travel provider websites in the U.S. Q2 2023, by share of voice

- Premium Statistic Most downloaded travel apps in the U.S. 2022, by aggregated number of downloads

- Premium Statistic Number of aggregated downloads of leading online travel agency apps in the U.S. 2023

- Basic Statistic American Customer Satisfaction Index for internet travel companies U.S. 2002-2023

- Premium Statistic American Customer Satisfaction Index for hotel companies in the U.S. 2008-2023

Leading holiday travel provider websites in the U.S. Q2 2023, by share of voice

Leading travel brands in the United States in 2nd quarter 2023, by share of voice

Most downloaded travel apps in the U.S. 2022, by aggregated number of downloads

Most downloaded travel apps in the United States in 2022, by aggregated number of downloads (in millions)

Number of aggregated downloads of leading online travel agency apps in the U.S. 2023

Number of aggregated downloads of selected leading online travel agency apps in the United States in 2023 (in millions)

American Customer Satisfaction Index for internet travel companies U.S. 2002-2023

American Customer Satisfaction Index Scores for internet travel companies in the United States from 2002 to 2023

American Customer Satisfaction Index for hotel companies in the U.S. 2008-2023

American Customer Satisfaction Index scores for hotel companies in the United States from 2008 to 2023

- Premium Statistic U.S. hotel and motel industry market size 2012-2022

- Premium Statistic Number of hotel jobs in the U.S. 2019-2022

- Premium Statistic ADR of hotels in the U.S. 2001-2022

- Premium Statistic Occupancy rate of the U.S. hotel industry 2001-2022

- Premium Statistic Revenue per available room of the U.S. hotel industry 2001-2022

- Premium Statistic Change in monthly number of hotel bookings in the U.S. 2020-2023

- Premium Statistic YoY monthly change in number of online hotel searches in the U.S. 2020-2023

U.S. hotel and motel industry market size 2012-2022

Market size of the hotel and motel sector in the United States from 2012 to 2022 (in billion U.S. dollars)

Number of hotel jobs in the U.S. 2019-2022

Number of hotel jobs in the United States from 2019 to 2022, with a forecast for 2023 (in millions)

ADR of hotels in the U.S. 2001-2022

Average daily rate of hotels in the United States from 2001 to 2022 (in U.S. dollars)

Occupancy rate of the U.S. hotel industry 2001-2022

Occupancy rate of the hotel industry in the United States from 2001 to 2022

Revenue per available room of the U.S. hotel industry 2001-2022

Revenue per available room (RevPAR) of hotel industry in the United States from 2001 to 2022 (in U.S. dollars)

Change in monthly number of hotel bookings in the U.S. 2020-2023

Year-over-year monthly change in number of hotel bookings in the United States from 2020 to 2023

YoY monthly change in number of online hotel searches in the U.S. 2020-2023

Year-over-year monthly change in number of online hotel searches in the United States from 2020 to 2023

Attractions

- Premium Statistic Leading museums by highest attendance worldwide 2019-2022

- Basic Statistic Most visited amusement and theme parks worldwide 2019-2022

- Premium Statistic U.S. amusement park industry market size 2011-2022

- Premium Statistic Landmarks most recommended visitors in the U.S. 2022

Leading museums by highest attendance worldwide 2019-2022

Most visited museums worldwide from 2019 to 2022 (in millions)

Most visited amusement and theme parks worldwide 2019-2022

Leading amusement and theme parks worldwide from 2019 to 2022, by attendance (in millions)

U.S. amusement park industry market size 2011-2022

Market size of the amusement park sector in the United States from 2011 to 2022 (in billion U.S. dollars)

Landmarks most recommended visitors in the U.S. 2022

Most recommended landmarks by visitors in the United States as of September 2022

City tourism

- Basic Statistic City destinations with the highest direct travel and tourism GDP worldwide 2022

- Premium Statistic World's highest-priced business travel destinations Q4 2022

- Basic Statistic Selected cities with the highest hotel rates in the U.S. as of September 2023

- Basic Statistic Most affordable cities for backpacking in the U.S. 2023, by daily price

- Premium Statistic Average price per night of Airbnb listings in selected U.S. cities 2024

- Premium Statistic Number of Airbnb listings in selected U.S. cities 2024

City destinations with the highest direct travel and tourism GDP worldwide 2022

Leading city tourism destinations worldwide in 2022, ranked by direct contribution of travel and tourism to GDP (in billion U.S. dollars)

World's highest-priced business travel destinations Q4 2022

Most expensive cities for business tourism worldwide in 4th quarter 2022, by average daily costs (in U.S. dollars)

Selected cities with the highest hotel rates in the U.S. as of September 2023

Selected cities with the most expensive hotel rates in the United States as of September 2023 (in U.S. dollars)

Most affordable cities for backpacking in the U.S. 2023, by daily price

Most affordable cities for backpacking in the United States as of January 2023, by daily price (in U.S. dollars)

Average price per night of Airbnb listings in selected U.S. cities 2024

Average price per night of Airbnb listings in selected cities in the United States as of February 2024 (in U.S. dollars)

Number of Airbnb listings in selected U.S. cities 2024

Number of Airbnb listings in selected cities in the United States as of February 2024

Sustainable tourism

- Premium Statistic Travelers who find sustainable travel important in the U.S. 2022

- Premium Statistic Share of travelers that plan to make sustainable travel choices in the U.S. 2022

- Premium Statistic How much more travelers would pay to make a trip more sustainable in the U.S. 2022

- Premium Statistic U.S. consumers who have paid extra for sustainable travel in the past two years 2022

- Premium Statistic U.S. consumers willing to pay extra for a sustainable travel provider 2022

- Premium Statistic Share of U.S. travelers that feel guilty over non-eco-friendly past travel 2022

- Premium Statistic Reasons travelers were against staying in sustainable hotels in the U.S. 2022

Travelers who find sustainable travel important in the U.S. 2022

Share of travelers that think sustainable travel is important in the United States as of February 2022

Share of travelers that plan to make sustainable travel choices in the U.S. 2022

Share of travelers that intend to make more sustainable travel decisions in the United States as of March 2022

How much more travelers would pay to make a trip more sustainable in the U.S. 2022

Extra cost travelers would be willing to pay to make a trip more carbon friendly in the United States as of March 2022

U.S. consumers who have paid extra for sustainable travel in the past two years 2022

Share of consumers that have paid extra for sustainable travel in the past two years in the United States as of February 2022

U.S. consumers willing to pay extra for a sustainable travel provider 2022

Share of consumers willing to pay extra for a sustainable travel provider in the United States as of February 2022

Share of U.S. travelers that feel guilty over non-eco-friendly past travel 2022

Share of travelers that experience guilt over past trips not being sustainable in the United States as of August 2022

Reasons travelers were against staying in sustainable hotels in the U.S. 2022

Reasons travelers were against staying in a hotel with sustainable practices in the United States as of August 2022

- Premium Statistic Priorities when choosing a leisure travel destination in the U.S. 2023, by generation

- Premium Statistic Leading destinations travelers intend to visit in the next 12 months in the U.S. 2023

- Premium Statistic Trust in travel and hospitality brands in the U.S. 2023, by brand type

- Premium Statistic American Customer Satisfaction Index: travel and tourism industries in the U.S. 2023

Priorities when choosing a leisure travel destination in the U.S. 2023, by generation

Main factors for choosing a leisure travel destination among adults in the United States as of May 2023, by generation

Leading destinations travelers intend to visit in the next 12 months in the U.S. 2023

Leading leisure travel destinations travelers intend to go to in the next 12 months in the United States as of September 2023

Trust in travel and hospitality brands in the U.S. 2023, by brand type

Level of trust in travel and hospitality brands in the United States as of September 2023, by brand type

American Customer Satisfaction Index: travel and tourism industries in the U.S. 2023

American Customer Satisfaction Index for the travel and tourism sector in the United States in 2023, by industry

Further reports Get the best reports to understand your industry

Get the best reports to understand your industry.

Mon - Fri, 9am - 6pm (EST)

Mon - Fri, 9am - 5pm (SGT)

Mon - Fri, 10:00am - 6:00pm (JST)

Mon - Fri, 9:30am - 5pm (GMT)

UN Tourism | Bringing the world closer

The first global dashboard for tourism insights.

- UN Tourism Tourism Dashboard

- Language Services

- Publications

share this content

- Share this article on facebook

- Share this article on twitter

- Share this article on linkedin

UN Tourism Data Dashboard

The UN Tourism Data Dashboard – provides statistics and insights on key indicators for inbound and outbound tourism at the global, regional and national levels. Data covers tourist arrivals, tourism share of exports and contribution to GDP, source markets, seasonality and accommodation (data on number of rooms, guest and nights)

Two special modules present data on the impact of COVID 19 on tourism as well as a Policy Tracker on Measures to Support Tourism

The UN Tourism/IATA Destination Tracker

Un tourism tourism recovery tracker.

UN Tourism Tourism Data Dashboard

- International tourist arrivals and receipts and export revenues

- International tourism expenditure and departures

- Seasonality

- Tourism Flows

- Accommodation

- Tourism GDP and Employment

- Domestic Tourism

International Tourism and COVID-19

- The pandemic generated a loss of 2.6 billion international arrivals in 2020, 2021 and 2022 combined

- Export revenues from international tourism dropped 62% in 2020 and 59% in 2021, versus 2019 (real terms) and then rebounded in 2022, remaining 34% below pre-pandemic levels.

- The total loss in export revenues from tourism amounts to USD 2.6 trillion for that three-year period.

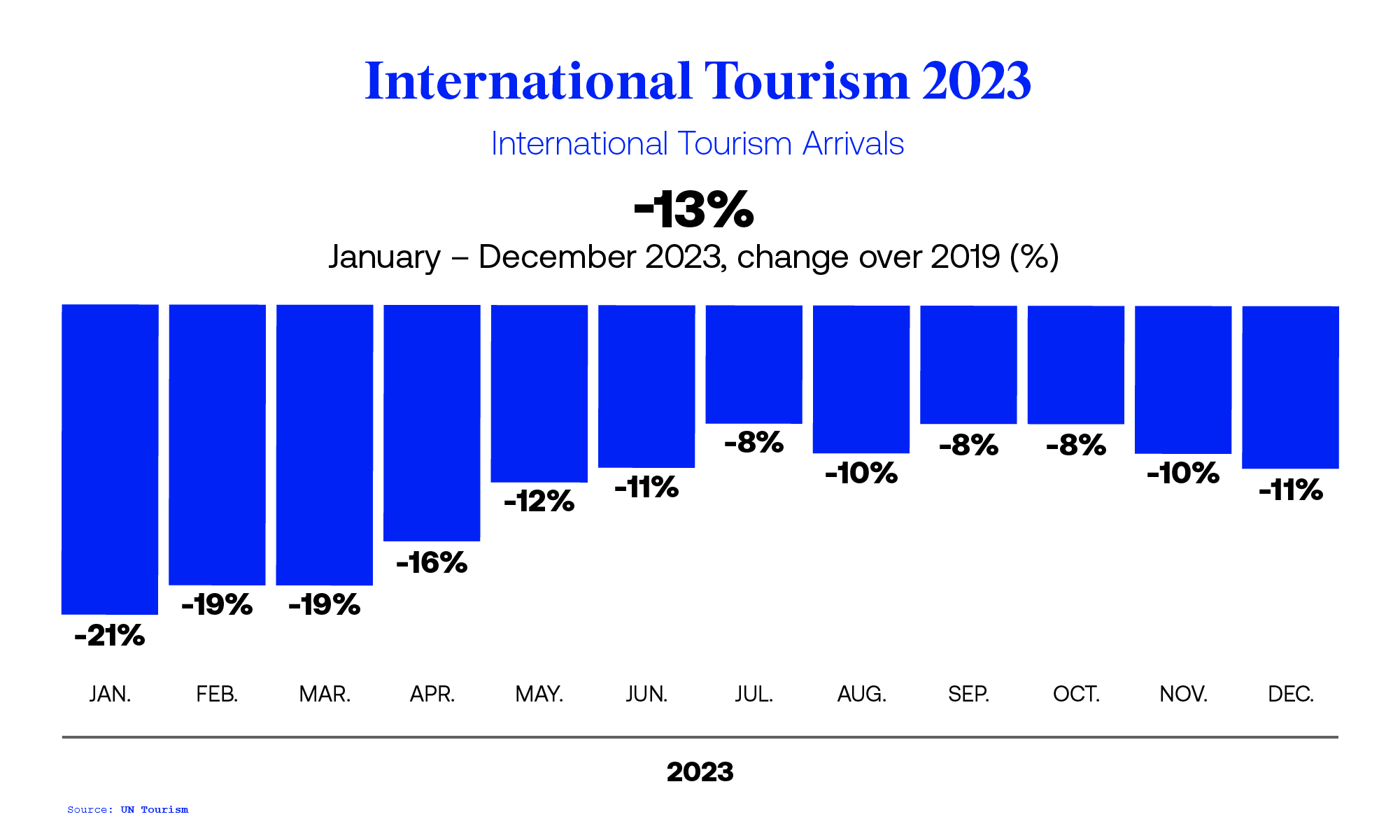

- International tourist arrivals reached 88% of pre-pandemic levels in January-December 2023

COVID-19: Measures to Support Travel and Tourism

- Hotels & Accommodation

- Travel Agencies & Travel Booking Websites

- Car rental & Parking

- Bus, train and transfer

- Experiences & activities

- Sunglasses, glasses & lenses

- Entertainment (Books, games, fun etc.)

- Car & motorcycle

- Sport & adventure

- Business & studies

- Health & beauty

- Clothing & fashion

- Baby & children

- For the holiday property

- Equipment, travel gadgets and other

- Exclusive travel discounts

30+ Denmark Tourism Statistics, Numbers and Trends (2022)

Updated on November 6, 2023 by Axel Hernborg

Before 2020, Denmark’s tourism industry had a string of record years, and it’s now on its way back to where it was before the corona pandemic. Every year, up to 12.8 million foreign tourists visit Denmark, with the capital Copenhagen seeing an 88 percent growth in overnight visitors in the last decade. As a result, Copenhagen is at the forefront of a very favourable trend in Denmark’s tourism sector, and one of the most frequently visited cities in Northern Europe, according to tourism statistics.