Savvy Travel Advice

Thomas Cook History: The Tale of the Father of Modern Tourism

Last updated: March 21, 2021 - Written by Jessica Norah 42 Comments

Do you know who Thomas Cook was and what contribution he made to the history of travel? Perhaps you have heard the name, seen it on the travel agencies that still carry his name, or maybe you’ve even taken a Thomas Cook tour. But my guess is that, like me, you don’t know too much about the man or how he fits into the history of travel.

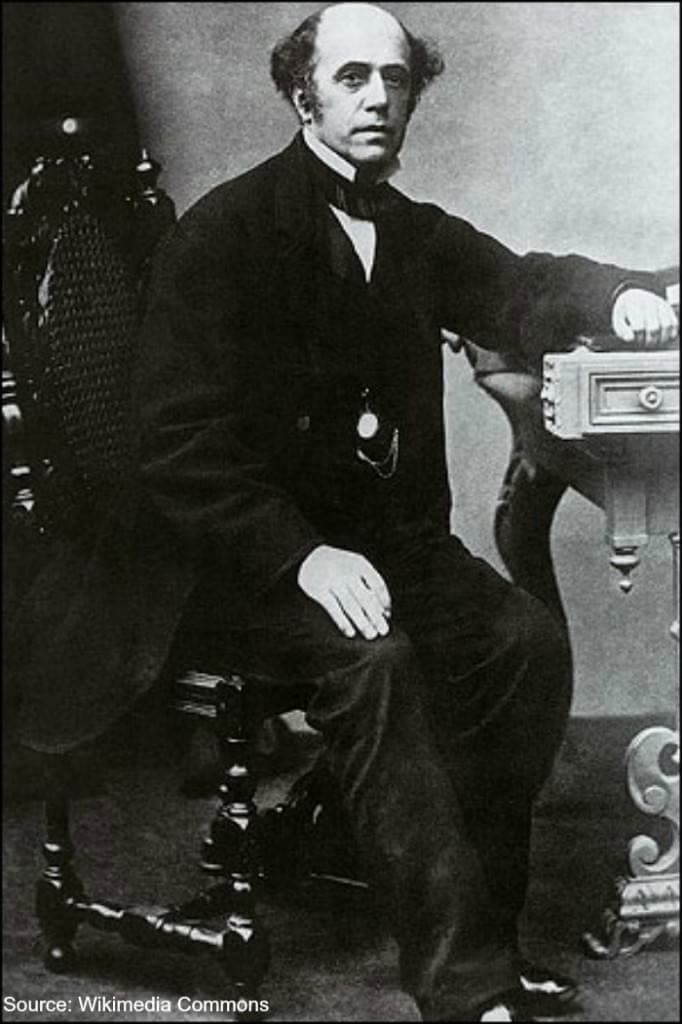

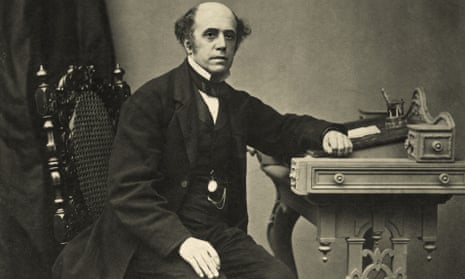

Thomas Cook was a passionate man who was born into a world where most working class people worked long 6-day weeks and never traveled more than 20 miles from their home towns. Thomas would begin work at age 10, laboring in a vegetable garden for 1 penny per day; but with a lot of determination and hard work, this working class man would eventually build one of the largest travel companies in the world.

This post is dedicated to the memory of Thomas Cook and his role in history and will give you a good overview of Thomas the man, Thomas the travel pioneer, and a glimpse of what it was like to travel in the Victorian age.

Table of Contents:

Who was Thomas Cook?

Thomas Cook was born in 1808 in the small town of Melbourne, England but would be best known for his time living in Leicester. He would finish his schooling at age 10 to begin working, often for only a penny a day, to help support his family.

Throughout his life, Thomas Cook would work as a Baptist preacher, carpenter, furniture maker, printer, publisher, political advocate, and travel organizer. As a Baptist preacher, he would walk thousands of miles and earned so little that he often worked in the dark to conserve candles and oil.

After seeing the effects of drunkenness at an early age, Cook believed that alcohol abuse was one of the major roots of the many social problems in the Victoria era and would spend much of his time and talents supporting the Temperance movement in England for the rest of his life. In fact, Cook’s beginnings as a travel organizer would come about because of his temperance beliefs.

In 1841, he would arrange for a special train to take over 500 people from Leicester to Loughborough to attend a temperance meeting. For 1 shilling, passengers got round trip train travel, band entertainment, afternoon tea, and food. Not a bad deal!

T he Birth of Thomas Cook & Son

Then in 1845, he would organize his first railway excursion for profit, and the following year he would begin offering trips outside England to Scotland, a country that captivated Cook and would remain one of his favorite destinations. For many of his early passengers, this was their first time aboard a train and the furthest distance they’d ever traveled from their home.

His trips kept getting bigger and in 1851, Thomas got the chance to organize railway travel and travel accommodations for people from the provinces to travel to London to attend the Great Exhibition orchestrated by Prince Albert. Thomas would transport over 150,000 people to London during the 6 months of the exhibition. This was one of the largest events in England and one of the largest movements of people within Britain!

Up until this point in time, most people in the provinces would be unlikely to travel to a town 20 miles away, let alone to the city of London. It must have been quite a shock for many people, who likely had never attended an event bigger than a county agricultural fair, to witness the Great Exhibition, where many of the greatest industrial inventions of the time were on display, in the bustling capital city of London.

His early tours would be marketed towards the working class, but later his company would go on to escort more middle class passengers and even organize travel for royalty, the military, and other important figures given his increasing reputation for being able to efficiently organize travel.

Interestingly, a large percentage of Cook’s travelers would be single or unescorted women who likely would not have been able to travel on their own (remember these are the days of Gone with the Wind ), but being part of an escorted tour provided them with both protection and independence.

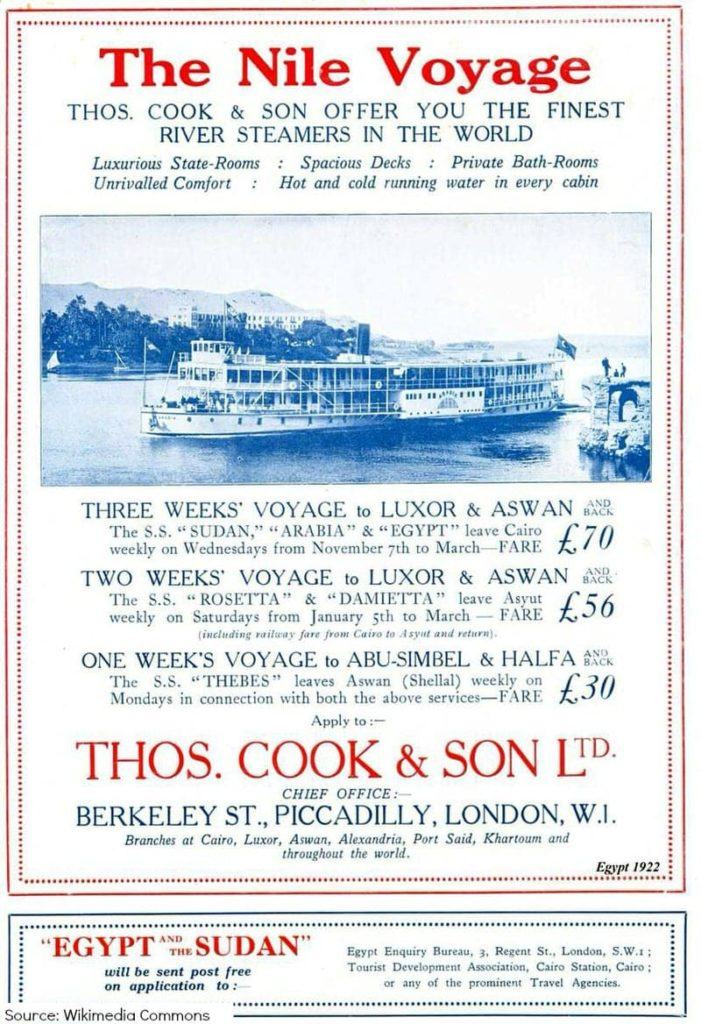

Cook would rapidly expand operations, escorting tours throughout Europe, North America, and even led the first commercial tour around the world. But perhaps no destination was more sacred to Thomas than his tours to Egypt and the Middle East. Here Thomas could witness firsthand the Biblical lands he had read and preached about all his life, and spending time in the Holy Land was truly a realization of many of his dreams as a young man.

A Man with Many Personal Obstacles and Struggles

Although Thomas Cook & Son would thrive and go on to become one of the largest travel agencies in the world, things did not work out as well for Cook in his personal life. Thomas’ father died when he was very young as did his stepfather, and young Thomas was left to be raised by his widowed mother.

As an adult, he would suffer the tragic sudden death of his only daughter Annie—a young woman on the cusp of marriage—who shared a close relationship with her parents. Thomas’ wife would suffer a long period of ill health following her daughter’s death, eventually dying and leaving Thomas alone with his own failing health that left him almost blind.

In his later years, he had a very strained relationship with his only son and business partner John Mason Cook. Thomas felt that he was being pushed aside in his own company and eventually John Mason Cook would take over all operations from his father. The father and son never truly reconciled and spent very little time together towards the end of his life.

While Thomas’ poor health and eyesight made it increasingly difficult, he continued to be active in travel and temperance activities until near the end of his life. His son would continue to expand the travel business.

What was it like to Travel During the Victorian Era?

Thomas lived during the reign of Queen Victoria—the Victorian era—and while romantic imaginings of spending time aboard the famous Oriental Express, sailing on luxury White Star Line steamships, and staying in grand palatial hotels may have been partially true of the wealthiest of travelers, these are far from the accommodations you could expect as a working class or middle class traveler.

Before widespread railway transport, the stagecoach reigned as the quickest way to get around and only the wealthy could afford such conveniences. So poorer people often walked, hitched rides on the back of wagons and carts, or, if lucky, rode a horse or donkey. In the early days of railway travel, third class train accommodations were open wagons, some without seats, where passengers would have to worry about the wind, sun, dust, locomotive smoke, and glowing hot embers.

During Cook’s travels—particularly his early trips—you would need to worry about germs and disease as very little was understood about germs at the time and the lack of widespread refrigeration and hot water heightened the chances of disease. Restaurants, flush toilets, and even running water were not staples in Great Britain, let alone the rest of the world. Communication was slow and done primarily by postal mail, sometimes taking weeks to confirm reservations or transmit a message back home.

However, things were not all bad. During Thomas’s life so much would change that would make travel faster, cheaper, and more comfortable than ever before. Improvements in the postal service, use of the steam engine, opening of the Suez canal, and the great expansion of the railways would make it possible for Thomas Cook to accomplish things that would not have been possible a generation before him.

Thomas Cook’s tours, with their discounted organized group rates, made it possible for a lot of working and middle class people to travel for the first time. Cook believed that travel could help educate and enlighten people who, like him, often did not have a proper school education, eliminate prejudices and bigotry, and be a healthy leisure alternative to visiting pubs, gambling halls, and whorehouses.

However, these new travel opportunities for the lower classes was not something that was widely appreciated by many of those in the upper classes of society. Until the nineteenth century, popular tourist destinations were almost exclusively the playground of the wealthy who could afford the time away and expensive cost of travel. The upper classes did not want to mix with the lower classes when traveling.

As Thomas Cook and others began to offer affordable excursion tours to popular destinations such as English country homes (e.g., Chatsworth House), the Rhine River valley, the French Riviera, Egyptian pyramids, and the Swiss Alps, wealthy travelers complained about what they saw as a bunch of uncouth, uneducated common people invading their exclusive travel paradises.

They criticized Thomas Cook and the excursion travelers, and this criticism likely wounded Thomas, who although he strongly believed in the right for all people to be able to travel, he also strived to be accepted by the upper echelons of society. Despite his success, he never was accepted by the upper classes as he was not of gentle birth, but was a working man and a Baptist in a country still largely controlled by wealthy Anglicans.

However, despite all the criticism, the demand for discounted organized travel would only continue to increase. The number of travelers from London who crossed the Channel to continental Europe rose from 165,000 in 1850 to 951,000 by 1899. Travel agencies and organized travel were here to stay.

Why Thomas Cook was a Travel Pioneer

Thomas Cook was a travel pioneer who built one of the largest travel businesses in the world, a business that started very humbly as a way to transport travelers to nearby temperance meetings. Thomas was able to “organize travel as it was never organized before” and with the help of the railways and the steam engine, he was able to do it on a scale that would have never before been possible.

Although not the first to come up with most of the ideas, Thomas would make things like travel vouchers, traveler’s cheques, and printed guidebooks common and widespread. Cook would use his talents as a printer to print travel advertisements, bulletins, magazines, guidebooks, and train timetables. In fact, Thomas Cook Continental Timetables would be published from 1873 to 2013 (last edition was published in August 2013) and were for many decades considered the bible for European train travelers.

His religious fervor would make him seek out exotic locations such as the Middle East and his determination would lead to Thomas Cook & Son opening offices around the world. Perhaps his greatest legacy is that he helped make it possible for a new group of people to engage in leisure travel. Cook understood well the drudgery of hard work and trying to support oneself on a meager income, and his tours provided working and lower middle class people the opportunity to explore a world they could have only have read about otherwise.

The Thomas Cook & Son name continued to exist as a travel company, offering travel tours until 2019. The company traded for 178 years. But it had not been a family-run business by the Cook family since the 1920’s when Thomas Cook’s grandsons, Frank and Ernest, sold the company to the Belgian Compagnie Internationale des Wagons-Lits et des Grands Express Européens, operators of most of Europe’s luxury sleeping cars, including the Orient Express .

In the 1940’s it would become state-owned by the British Transport Holding Company. It would continue to change hands over the years. In 2001, it would become owned solely by C&N Touristic AG, one of Germany’s largest travel groups, who renamed the company, Thomas Cook AG.

Thomas Cook became one of the world’s largest travel agencies and the oldest in the UK. Its famous slogan developed by advertising expert Michael Hennessy: “Don’t just book it….Thomas Cook it” became well-known around the world.

The Bankruptcy and Closure of the Thomas Cook Travel Agency in 2019

Sadly, the travel agency and airline that carried the Thomas Cook named declared bankruptcy in September 2019, leaving about 150,000 British travelers “stranded” all over the world (as well as a number of other nationalities). Perhaps the most devastating effect has been the immediate loss of thousands of jobs for people in the UK and abroad.

The travel agency, however, was properly insured and protected and most of those who booked a trip can apply for a refund, and those left “stranded” on trips were repatriated by the UK. It was the largest repatriation effort since World War 2.

In October 2019, it was announced that all the Thomas Cook travel agency offices in UK will be taken over by Hays Travel and rebranded under their name. Most of the reopened offices are being staffed by former Thomas Cook employees. Hays Travel is now the largest independent travel agency in the UK, and you can read more about them here .

In 2020, the COVID-19 pandemic wreaked havoc on all sectors of the global travel industry and Hays Travel was forced to close its travel offices in the UK for a large part of the year. Many of the former UK Thomas Cook offices have now been permanently shuttered and many of the employees who had been rehired were sadly made redundant. You can read more about that here .

Although the future of the Thomas Cook name in travel may be uncertain, I would be very surprised if the name does not continue to be associated in some way with a travel agency.

In fact, although all the UK based companies have stopped trading, some Thomas Cook owned resorted, like Cook’s Club are still operating. Some of its subsidiaries in some other countries are still trading as normal but are also in danger of closure.

What I Learned from Reading about Thomas Cook

Thomas Cook was a quite extraordinary self-made man. He had so many occupations and business ventures and so many setback and failures, even declaring bankruptcy at one point, but he was so persistent and never gave up. He was a passionate man who fought for his Baptist faith, beliefs in equality for all people, and for temperance.

In addition to being impressed by the determination and innovativeness of Thomas Cook himself, I was also quite intrigued in the ways that travel has changed and the ways it has not. We have come a long way since Thomas Cook escorted his first tour as we can travel so much lighter, faster, and more conveniently than would have seemed possible to Victorian age travelers who would accept unheated train cars, month-long ocean crossings, and hotels without hot water.

Cook, a teetotaler until his death, would likely be shocked by the tourism industry’s promotion of sun, sea and sex and the partying and drinking associated with many travel destinations. Indeed, many of these locations are the most popular destinations for British travelers on package holidays.

However, some things have not changed very much. Criticisms of organized travel remain with the notion that independent travel is better and people love to make the subjective “traveler” versus “tourist” distinction. There are also still locations that remain primarily the playgrounds of the wealthy although never like during the Victorian age. Travel remains class segregated as those who can afford to do so can fly in first class seats, dine in the finest restaurants aboard ships, and sleep in the best cabins with little need to spend much time with other class passengers.

One of the things that I found perhaps the most interesting was the destinations promoted by Thomas Cook still remain, with few exceptions, major tourist destinations today. The country house of Chatsworth House is one of the most notable country houses in England today and people are still flocking to the Scottish highlands, Paris, Rhine River Valley, Swiss Alps, Egypt, the ancient city of Petra, Australia, and most of the other destinations promoted by Thomas Cook in the 1800’s.

While things have changed in some ways beyond recognition, many of the world’s wonders and great destinations continue to awe visitors as they must have awed those first pioneer tourists led by Thomas Cook.

Want to Learn More about Thomas Cook and Victorian Age Travel?

Resources about Thomas Cook (I used these in writing this article) :

-Hamilton, Jill. (2005). Thomas Cook: The Holiday Maker . The History Press.

-Piers Brendon. (1991). Thomas Cook – 150 Years of Popular Tourism . Martin Secker & Warburg Ltd.

-Withey, Lynne. (1997). Grand Tours and Cook’s Tours – A History of Leisure Travel, 1750 to 1915 . William Morrow & Co. [This book focuses on a broader view of the history of travel including a lot of attention to Thomas Cook tours and their impact on tourism]

-A great Wikipedia link to some of Thomas Cook’s Traveler Handbooks: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Cook%27s_Travellers_Handbooks

Another book related to Thomas Cook on my to-read list:

-Swinglehurst, Edmund. (1974). The Romantic Journey – The Story of Thomas Cook and Victorian Travel . Pica Editions.

So what do you think about Thomas Cook and the Victorian Age of Travel? If you are interested in another article on travel during the Victorian age, check out our post on t wo American women who race around the world in less than 80 days .

Share this Post!

There are 42 comments on this post.

Please scroll to the end to leave a comment

Baskin Post author

February 28, 2024 at 3:26 am

Wow, so fascinating to read about the history of Thomas Cook, the visionary behind modern tourism. I definitely learned a lot from this about how His legacy continues to shape travel and hospitality industries, very educational post!

Jessica & Laurence Norah Post author

February 28, 2024 at 10:20 am

Thanks for taking the time to comment and glad to hear you enjoyed our article on Thomas Cook. And yes his contributions to the travel industry can definitely still be seend today!

Best, Jessica

Chandra Gurung Post author

May 9, 2023 at 4:15 am

Very interesting post, thanks for the great travel History !!

May 13, 2023 at 8:06 am

Hi Chandra,

Glad you enjoyed our post on Thomas Cook, thanks for taking the time to comment!

Karim Post author

October 29, 2022 at 3:01 pm

Thanks for your blog post on Thomas Cook, very helpful, nice to read.

October 31, 2022 at 10:04 am

Thanks for taking the time to comment, glad you enjoyed our post on Thomas Cook and a bit of the history of the man and his company 😉

Jeanne Gisi Post author

May 24, 2022 at 1:06 pm

While cleaning out some boxes filled with mementos of my travels over the years, I came upon an Itinerary prepared by Thos. Cook & Son for a 6 week European trip in 1965 for my parents & I (I was 13)! It was so fascinating to see the level of detail for each stop, which included England, France, Italy, Spain & Germany; and the beautiful cover & fancy paper used to produce the itinerary. I went looking on the internet to see if they were still in existence & found your blog, which I found so informative about the founder & the many iterations the company had gone through. Probably the most amazing detail in this itinerary was discovering that for hotels in 4 different cities, train rides, rental car & private transport for the entire trip was shown at $328 per person! Astounding! Appreciated reading your historical information about this venerable company.

May 25, 2022 at 5:10 am

So glad you enjoyed our article on the history of Thomas Cook.

Oh, wow, that must be wonderful finding old treasures from your family travels. I love things like that. And yes a 6 week trip for $328 per person (about $3,000 per person in today’s money) would still be a good value today for all that was included for a 6-week trip. And it would have taken longer to put together an itinerary then as the travel agent would have needed to call or mail for inquiries and reservations rather than clicking buttons on a computer.

Yes, Thomas Cook has gone through a lot in recent years. Hays Travel purchased most of the Thomas Cook offices/stores and hired back a lot of the staff in 2019. But then of course the COVID-19 pandemic came soon after, and many of the stores have since re-closed and a number of people had to be let go. For example, our local travel store (in Bath, England) went from a Thomas Cook to a Hays Travel to being empty again in about a year’s time. It will be interesting to see what will happen with traditional travel agencies like this as international travel goes back to 2019 levels and if they will continue to flourish in the face of online competitors.

Ruth Deeks Post author

March 21, 2021 at 8:39 am

Very interesting. My parents who were Baptist missionaries in India had told me that Thomas Cook was a Baptist and gave a special rate to missionaries travelling by boat to and from India, the journey taking 5 weeks approx. I am talking about the 1930s to 1950s. What a shame the The Thomas Cook co. was sold out of the family and went bankrupt.

March 21, 2021 at 9:05 am

Glad you enjoyed our article on Thomas Cook and the history of his travel business. He is an interesting man combining his religion with travel.

Yes, it is sad that the Thomas Cook business went bankrupt. Sadly, the UK travel company which took over most of the Thomas Cook offices in the UK, Hays Travel, has now had to close many of these offices in 2020 due to the coronavirus. This has also sadly left many of the former Thomas Cook employees, many of which were then re-hired by Hays Travel, without a job again. It’s been a very tough couple of years for UK travel agents. Hopefully, 2021 will be a better year for them.

Uwingabire Faustine Post author

November 28, 2020 at 1:03 pm

Hello I was inspired by the theory of Thomas Cook, but wanted to know above all that why was he important in tourism industry?

November 29, 2020 at 7:05 am

Glad you enjoyed our post on Thomas Cook and learning about his life. Hopefully you found your answer about why Thomas Cook was important in the tourism industry from the article. But if not, I’d go back and read the “Why Thomas Cook was a Travel Pioneer” section as that covers a good summary of his achievements related to travel and his importance in the tourism industry.

If you have any further questions, please let me know!

Seba Campos Post author

July 30, 2020 at 6:49 pm

Hi! I am a tourism student from Argentina, I really liked your article and it was extremely revealing for me. I’m working on the Thomas Cook story.

Do you have any information about his family? Why did they decide to sell the company? Why did your son remove him from the company? Thank you so much!

August 1, 2020 at 5:28 am

Glad that you are finding my article helpful in writing your paper on Thomas Cook.

If you are looking for additional information, I’d recommend checking out one of the books about Thomas Cook such as this one by Jill Hamilton published in 2005. The books will give you more details and context than you’ll find online. You should be able to buy it online through Amazon or ebay.

The Thomas Cook company website used to have some good historical information but that information has all been removed since Thomas Cook closed in the UK.

Hope that helps, Jessica

Colin Post author

October 6, 2019 at 5:41 am

Hi Jessica, I was just searching about Thomas Cook after the recent bankruptcy as I was one of the people affected. Luckily for us, we were not on the tour and it was booked several months away, so it seems all will be well in terms of getting our money back. We also have plenty of time to rebook our holiday, so we are luckier than most.

What a great post and what a detailed history of Thomas Cook and his travel company. I have used Thomas Cook to book holidays for years and never knew anything about Thomas Cook, the man or his background. This was a very interesting read!

October 6, 2019 at 6:09 am

Sorry to hear that you were one of the people affected by the Thomas Cook bankruptcy and closure. But I am happy to hear that it sounds like you will receive a full refund for your booked trip and will have plenty of time to rebook your holiday.

So glad you enjoyed our post. Yes, the history of Thomas Cook as a person is very interesting and he was definitely a pioneer in the field of tourism. I am sure the Cook name will continue to be associated with a travel company in one way or another in the future since it is so well recognized worldwide.

Happy travels, Jessica

Eran Post author

December 26, 2018 at 10:21 pm

Hi, Great post! Towards the end of it you mention that a lot of things haven’t changed in travel. However, I think in recent years, with the rise of low-cost flights, now tourism is more reachable to all segments than ever before…

December 27, 2018 at 3:37 am

Hi Eran, Yes, it is amazing how much hasn’t changed and in other ways how much things have changed since the time of Thomas Cook!

I do think that low cost travel has enabled more people to travel, but in more recent times it is probably more due to better economic conditions in countries than things like budget airlines, as we are seeing huge increases in the number of travelers from places like India, China, and Latin America. Travel for leisure is commonplace in many countries, but still remains something for those with money as much of the world’s population can not often afford to travel internationally for leisure. According to Hans Rosling, it is estimated that only the richest 1 billion people in the world live where they can easily afford airplane tickets, and 2 billion people spend less than $2 a day.

Interesting to look at travel from a global perspective as it can be easy for Western people to take it for granted.

Alok kumar mandal Post author

August 17, 2018 at 8:15 am

very interesting and useful facts about Mr. Cook…

August 17, 2018 at 11:32 am

Hi Alok, Yes, Thomas Cook was an interesting man and we the see the effects of his legacy on modern travel all over the place, especially since we are now living in the UK. Best, Jessica

Bryant Kerr Post author

November 4, 2017 at 10:08 pm

I have a old traveling trunk that have the names Colonel Thomas Cook and Sons the other name is Lieutenant Colonel Rodger Young military number 03443 79 New Delhi does anyone know anything about this trunk

November 7, 2017 at 8:29 am

Hi Bryant, I don’t know anything about the trunk, but there is a fairly well-known American from Ohio that was in the military named Rodger Wilton Young although not sure if he was ever in New Delhi. There was also a Thomas Cook who served at the Addiscombe Military Seminary in 1837. But the Thomas Cook & Sons are probably just the ones that arranged the travel so you’ll probably have better luck tracking down Young. Best of luck!! ~ Jessica

Taranath Bohara Post author

January 31, 2017 at 5:09 am

I love this guy Thomas Cook, who helped bring affordable tourism to the world. Many people are involved and have followed his principles. He was a great who taught the lesson of tour and travel. Great blog post!

January 31, 2017 at 6:20 am

Hi Taranath, Thanks for taking the time to comment. Yes, I really love the story of Thomas Cook and I don’t think a lot of people know the influence he had on the modern tourism industry but at least his name is still carried on in the company he founded. Glad you enjoyed our article! Best, Jessica

LOUIS GEEN Post author

January 31, 2017 at 9:11 am

Could this be the same man? I am a Freemason and a member of the Port Natal Masonic Lodge in Durban, South Africa. The Lodge is almost 160 years old, having been consecrated on 12th August 1858. According to our records Thomas Cook was Master of the Lodge during the Masonic year 1883 – 1884. The Lodge is in possession of a beautiful oil painting of Thomas Cook that was donated by him to the Lodge. Until I discovered Thomas Cook’s name in the Port Natal Lodge’s records, I was not aware that the Father of Modern Tourism resided in South Africa. Could our Thomas Cook be the same man that turned tourism into the industry it has become?

January 31, 2017 at 10:22 am

Hi Louis, How interesting and thanks for commenting again on this post! It is possible of course as Thomas Cook lived from 1808-1892, but I don’t think that Thomas Cook was a freemason and I don’t remember reading about him spending time in South Africa. Thomas Cook is a fairly common name. However, I am no expert, and to find out for sure, I’d contact the Thomas Cook Group and they should be able to easily verify if the painting is of the same Thomas Cook of the travel agency. Let me know if you have any difficulty contacting them and I’d love to hear what you find out even if it turns out to be another Thomas Cook! Best Jessica

Tim Post author

June 7, 2016 at 7:22 am

Thanks for all this information on Thomas Cook! I am looking to for copy of one of the recommended books on Amazon!

travelcats Post author

June 13, 2016 at 7:30 am

Hi Tim, You are very welcome for the information on Thomas Cook. Amazing story and an important person in modern travel history and the current state of tourism. Good luck finding the book! ~ Jessica

Kerstin Post author

May 24, 2016 at 6:43 am

Meanwhile, Diccon Bewes has written a book on Cook’s Grand Tour of Switzerland, which I highly recommend to anybody interested in Victorian era travel: Slow Train to Switzerland , ISBN 9781857886092.

May 24, 2016 at 7:27 am

Hi Kerstin, Thanks for that book recommendation. I have not read it but it does have good reviews and I think it would be great for those readers interested in Thomas Cook tours to Switzerland or early mass tourism to the Alps! Best, Jessica

Louis Geen Post author

November 12, 2014 at 1:26 am

Thomas Cook was certainly an interesting character. Another interesting fact about this amazing man is that he was a Freemason and that he was Master of the Port Natal Lodge in Durban, South Africa, from 1883/1884. The Lodge now 156 years old, still exists and has in its possession a beautiful oil painting of Thomas Cook in its original gilded frame, which he donated to the Lodge.

November 15, 2014 at 9:28 am

Hi Louis, I did not know this. I don’t recall any reference to the freemasons or even South Africa during my readings and research on Thomas Cook. Do you have a reference for this for those interested in reading more about this? I couldn’t find any info about the lodge online.

Nic Post author

November 7, 2013 at 9:03 am

The quotes from Thomas Cook are great.

November 7, 2013 at 10:14 am

Agreed:) I really like the one in the green box.

Meghan Post author

November 6, 2013 at 6:24 pm

This is so interesting! I’m always so fascinated by stories about travel in the past. I recently learned that it wasn’t until the last few centuries that people began traveling for pleasure. I’ve even read that in some parts of the world, people think it is a little strange for a person to travel just because, and not for some business or personal errand. But all this information I never knew. I’ve never even heard of Thomas Cook until now. Thanks for sharing!

November 7, 2013 at 10:12 am

I know, it is so interesting to read about travels in prior centuries. That’s interesting about how some people see travel as strange today but I imagine in places where people have very little money, leisure travel is not much of a possibility.

bevchen Post author

November 5, 2013 at 11:51 pm

I knew only some of this. It’s very interesting!

November 6, 2013 at 7:20 am

Yes, it is a fascinating history.

Meredith Post author

November 5, 2013 at 9:52 pm

Wow, I had no idea! I’d heard the name but didn’t fully realize the history behind it. I feel like I owe him a big thank you! Even now there are some places in the world that would’ve been difficult for me to see without a tour group. Fascinating!

November 6, 2013 at 7:19 am

Yes, there are definitely several places in the world that make more sense with organized travel or travel guides than on your own. Thomas Cook’s company actually also helped people book unecorted independent travel and just made all the travel arrangements, allowing people to do it on their own. BTW, did you see how he was also captivated by Scotland (made me think of you).

Kate Post author

November 5, 2013 at 5:19 pm

Not only am I amazed I didn’t know any of this, but I am fascinated as to how much history there really is behind Thomas Cook!

November 5, 2013 at 7:21 pm

Yes, it really is an interesting history. The British, like Thomas Cook, were really the pioneers that started the modern tourism industry. It didn’t hurt that the British Empire stretched across the world:)

Leave a Reply Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Notify me of replies to my comment (just replies to your comment, no other e-mails, we promise!)

Subscribe to our monthly Newsletter where we share our latest travel news and tips

We only ask for your e-mail so we can verify you are human and if requested notify you of a reply. To do this, we store the data as outlined in our privacy policy . Your e-mail will not be published or used for any other reason other than those outlined above.

- International edition

- Australia edition

- Europe edition

Thomas Cook's great expedition of 1861 – archive

24 May 1961: One hundred years ago, many people from the working classes had never ventured beyond their native town or village

Mr Thomas Cook’s working men’s excursion to Paris at Whitsuntide, 1861, was one of the earliest examples of a tour to a foreign country arranged primarily for the artisan classes.

In the previous 20 years Cook had become the pioneer travel agent; after his success in organising excursions to London for the Great Exhibition of 1851, he arranged a 31s return trip from Leicester to Calais for the benefit of visitors to the Paris Exhibition of 1855, and the following year he advertised “a grand circular tour on the Continent.”

The middle classes were already interested in the formation of travel clubs and agencies and Cook had also aroused the interest of some of the working-class population in taking a holiday – albeit a short one. Hitherto many had never ventured beyond their native town or village, and the exceptions had ventured only on short-distance excursions.

The idea of the working men’s excursion to Paris replaced an earlier proposal for a visit by a party of Rifle Volunteers – a suggestion which met with much criticism since it was feared that the purpose of such a visit might be misunderstood in France.

On December 17, 1860, it was announced that British subjects would be admitted to France without passports from January 1861, and this announcement coincided almost exactly with the arrival of a delegation in Paris for the purpose of organising an excursion by British working men during the following Easter or Whitsuntide holidays. A committee was formed in London under the chairmanship of Sir Joseph Paxton, and it decided to approach Thomas Cook. His co-operation was readily forthcoming since his enthusiasm for organising travel sprang from his faith in its educational benefits.

Undertaking to make arrangements at his own risk, Cook advertised the proposed trip principally in the Midlands and the North of England and 1,673 reservations were made. While the abolition of the French passport system simplified matters for him, negotiations with the two railway companies which operated the Folkestone-Boulogne route to Paris were difficult. The companies were not accustomed to agreeing to low fares on this route, and the Northern Railway of France in particular frowned upon providing cheap facilities – especially at Whitsuntide when it might prove especially annoying to other passengers.

The companies insisted on a guaranteed minimum of 500 passengers on the first train, and it was eventually agreed to limit the number on each train to 550, with each passenger restricted to 28lb. of baggage. A registration fee of 1s was charged and the fares were fixed at 20s return from London to Paris in covered third-class carriages, or 26s in second-class carriages.

The party did not consist exclusively of working men, but there were about two hundred employees from Titus Salts Cottonworks at Bradford and a large number of mechanics, the majority from the North. There were few from London. Married men were accompanied by their wives.

On Friday, May 17 the first party left London Bridge for the seven-day visit to Paris and on arrival at Boulogne it was greeted enthusiastically by a large crowd assembled on the quayside where a triumphal arch with the inscription “WELCOME TO BOULOGNE” had been erected.

There was a short break for refreshment, and great difficulties were experienced with the bread which was handed about “in immense poles at least two yards long.” Most of the tourists made their acquaintance with “vin ordinaire” before travelling through the night to Paris by the Northern Railway of France in order to arrive in the French capital “with the broad daylight.” There was one further stop for refreshment at Amiens.

Read article in full here

- Thomas Cook

- From the Guardian archive

- Travel & leisure

- Paris holidays

- Rail travel

- France holidays

Thomson and First Choice owner to scrap holiday brochures

A break with tradition: the end of the Thomson holiday brochure

Jetting off: Brits shun staycations for foreign holidays

Travellers fall victim to fake Airbnb site

EU referendum – when to buy your holiday money

French tax authorities seek €356m from Booking.com

Packed beaches and gridlock loom large as tourists swap terrorism hotspots for Spain

British Airways considers ditching free food in economy class

Miracle in Athens as Greek tourism numbers keep growing

Comments (…), most viewed.

Name: First Iron Rails

Region: Valleys of the Susquehanna

County: Montour

Marker Location: US 11 in Danville at Mahoning Creek

Dedication Date: May 12, 1947

, The Romance of Steel (New York: Books For Libraries Press), 1971.

D. H. B. Browser , Danvill, Montour County, Pennsylvania: A Collection of Historical and Biographical Sketches (Pittsburgh, PA: Lane S. Hart), 1881 (Reprinted 1976, Unigraphic, Evansville, IN).

Frank W. Diehl , A History of Montour County, PA (Berwick, PA: Keystone Publishing Co.), 1969.

Douglas Allen Fisher , Epic of Steel (New York: Harper and Row), 1963.

Arthur Toye Foulke , My Danville, Where the Bright Waters Meet (North Quincy, MA: The Christopher Publishing House), 1969.

The 1846 plan for India's first Railway line

By Kalakriti Archives

Dr. Alex Johnson

India's first railway opened in 1853, a 32 km line between Bombay and Thane. However, there was an earlier plan to build a line from Calcutta to Delhi, and this rare map from 1846, which helped hail the rise of Modern India, was prepared for the East India Railway Company's initial survey.

Map of the East Indian Railway (1846) by George Stephenson Kalakriti Archives

The construction of the railway system across India during the second half of the 19th Century utterly transformed the subcontinent’s society, communications and economy. Disparate regions that were separated by journeys that could last weeks could now take a few days, if not hours.

Peoples and cultures that historically had little contact with one another could now easily interact. Products in rural India that languished far from market could now be brought swiftly to cities and ports.

Map of the East Indian Railway, Showing the Line proposed to be constructed to connect Culcutta with the North West Provinces and the intermediate Civil & Military Stations, to accompany the report of the Managing Director of the East Indian Railway, 1849 by Unknown Kalakriti Archives

From a political perspective, it also allowed the British colonial regime to quickly move troops and civil servants around the country, solidifying its control over India.

The first railway completed in India was a 21 mile-long line of track running between Bombay and Thane, which opened in 1853. While seemingly a modest breakthrough, everyone knew that it was the prelude to a revolution – a pan-Indian Railway network.

In 1845, the East Indian Railway Company was formed with the objective of building a line from Calcutta to Delhi. Such a railway would connect the Company Raj’s capital with the ancient Mughal capital and would serve to unite India’s most populous regions.

The Gangetic Plain was India’s breadbasket and many cities such as Kanpur and Allahabad were increasingly important industrial centres.

The railway promised that, for the first time, products and peoples could be easily transported down through the plains and even to the seaport of Calcutta. The potential was enormous, and, if the railway were realized, it would dramatically transform Northern and Northeastern India.

The East Indian Railway Company was officially floated on 1 June 1845 with £4 million in investment capital – an enormous sum for the time.

Rowland Macdonald Stephenson (1808-95), an experienced railway engineer, was chosen as the Company’s first managing director. Stephenson and three surveyors immediately headed to Calcutta, arriving in July 1845.

George Huddleston, a later Director General of the Railway noted, Stephenson proceeded “with diligence and discretion which cannot be too lightly recommended, to survey the line from Calcutta to Delhi, through Mirzapore [Mirzapur], and so great and persevering were the exertions of himself and Staff that, in April, 1846, the surveys of the whole line were completed; important statistical information obtained and an elaborate report transmitted to your Directors in London.”

Copies of Stephenson’s manuscript surveys were given to the firm of the J. & C. Walker, the official mapmakers to the British East India Company (EIC). The Walker firm grafted Stephenson’s plotted proposed route of the railway onto one of its own existing general topographical maps depicting Central and Northern India, and printed the present bespoke map. Copies of the map were then supplied to the Directors to accompany Stephenson’s report.

The map is extremely rare as only a very small number of examples were ever issued. Nevertheless, it would have then served a very important role as the only authoritative graphic representation of the railway.

The East India Company, once an ambitious and hyperactive organization, by this time was beset by institutional fatigue and a lack of funds. While it recognized the value of the railways to India’s future, it proved too tired to provide any leadership and ended up presenting only bureaucratic obstacles to the railway builders. It was no surprise that following the Uprising of 1857 that Queen Victoria would put the “Honourable Company” out of its misery and replace it with Crown rule over India.

After three years of delays, in 1849, the EIC finally allowed the East Indian Railway Company to build an “experimental line” from Calcutta to Rajmahal (Jharkhand), a length of 100 miles.

In 1850, Stephenson appointed George Turnbull (1809-89), a highly experienced Scottish railway engineer, to lead the construction efforts. Turnbull would later gain great acclaim as the “First Railway Engineer of India”. Turnbull proceeded to survey the exact line of the new route and to design the Howrah Terminus, across the Hooghly from Calcutta, which, with 23 platforms, would soon become the largest rail station in Asia. Construction commenced in 1851 and proceeded slowly due to supply problems and the continued lack of cooperation from the EIC. The first stretch of line from Howrah to Hooghly, only 23 miles long, was opened for traffic in 1854. The construction then continued in the direction of Rajmahal.

Progress was further retarded by the Uprising of 1857, during which many supplies and pieces of track were stolen. A cholera epidemic in 1859 killed over 4,000 railway workers. Yet, the project still moved forward. The biggest technical obstacle that lay ahead was building a bridge over the 1-mile wide breadth of the Son River, the Ganges' largest southern tributary. This bridge (today’s Koillar or Abdul Bari Bridge) would turn out to be a great feat of engineering, being the longest bridge in India built before 1900. Commenced in 1856, it was not finished until 1862.

The line running all the way from Howrah to Benares was opened in 1862.

Another section of the line was being built separately along the Ganges Valley, with a line connecting Kanpur to Allahabad being completed in 1860, while Benares and Allahabad were connected in 1863. By 1866, all gaps between Howrah and Delhi were filled in and direct service along the entire line commenced.

Meanwhile, the pioneering, yet tiny, Bombay-Thane line had grown into the Great Indian Peninsula Railway. By 1870, it ran from Bombay to Allahabad, connecting the two great railways and making it was possible to traverse India in only a few days.

While the rail system had the effect of tightening the British Raj’s grip over India, over time, by allowing Indians from different parts of the country to easily interact with each other, it contributed towards fostering a coherent sense of national identity. In this way, it was a critical precondition to rise of the Indian Independence movement. Today, the custodian of the integrated national railway system, Indian Railways, employs over 1.3 million people, runs 151,000 km of track, and operates over 7,000 stations.

Author: Dr. Alex Johnson References 1. Cf. George Huddleston, George (1906), History of the East Indian Railway , (Calcutta, 1906) 2. Hena Mukherjee (1995), The Early History of the East Indian Railway 1845–1879 , (Calcutta, 1995) 3. M.A. Rao, Indian Railways , (New Delhi, 1988)

Qutb Shahi Heritage

Kalakriti archives, cosmology to cartography - sacred maps from the indian subcontinent, his highness the nizam's army, space-time and place: the culture of indian maps, cosmology to cartography - maps of the southern india region, cosmology to cartography - conflict of european players in the indian subcontinent, cosmology to cartography, cosmology to cartography - the maps depicting the early encounter with indian subcontinent, cosmology to cartography - maps depicting one india, cosmology to cartography - early players in the indian subcontinent.

Jump to Content

List of Contents

Diary of Lester Hulin: He crossed the plains in 1847 arriving in Oregon over the Applegate Trail. Mr. Hulin was an educated man and illustrated his diary with pencil sketches which are reproduced. There is a 4x5 mat print of Mr. Hulin. (Reprinted)

Autobiography of James Addison Bushnell

Narrative of John Corydon Bushnell

Diary of John J. Callison: The Callison family came from Scotland to America, living in Virginia, Kentucky and Hancock County, Illinois. This diary contains 10 pages, with a large print of the first page of the diary. John Callison died of cholera Aug. 23, 1852 and his family continued on to the Willamette Valley. Included is a geneaology of the Callison family.

Narrative of Basil N. Longsworth

Journal of Andrew S. McClure (2 versions)

Narrative of Benjamin Franklin Owen

Diary of Charlotte Emily Stearns: She was the wife of Bynon J. Pengra. Came to Oregon in 1853. Descended from Isaac Stearns who came to New England with the Winthrop Fleet in 1630. Fine 4x5 print of Mrs. Pengra as a young woman. Geneaology of her family. (Reprinted)

Diary of Agnes Stewart and Elizabeth Stewart

"Biographa" of Adam Zumwalt

Organizational Journal of an Emigrant Train of 1845 Captained by Solomon Tetherow: It also contains an account of the trail trip and family genealogy. A picture of Solomon Tetherow and family genealogy is included. (Reprinted)

Journal of George Belshaw: This journal describes the wagon train trip from Indiana to Oregon during the months of March thru September. Contains a picture and short family history. 56 pages. (Reprinted)

Diaries of Henry Clay Huston: Rare 1856 Rogue River Indian War Journal; also a diary kept on Huston's trip back to Indiana via the Isthmus and return to Oregon 1859-60. Author was an exceptionally well educated observer and writer. Huston's family history and author's picture included.

Civil War Period in Oregon - Elijah Lafayette Bristow Letters: Reproduction of a most unusual set of letters from Mr. Bristow's copy book, discussing with relatives and friends such things as politics, business in early Oregon and freighting to the Idaho mines.

Helen Stewart Diary: A recently discovered account by a young girl of travel from Pennsylvania to Oregon in 1853. Includes a genealogy of the Stewart family. This is a companion diary to the stories by her sisters, Agnes and Elizabeth Stewart, published as No. 9 by this Society.

Letters of Joseph and Esther Brakeman Lyman: Rare description of 1853 experiences on trip to Oregon in the Lost Wagon Train. Pictures of writers and genealogy of Brakeman and Wadsworth families.

Reuben Ellmaker (Oelmacher) Letters, 1854-1860: Written from Iowa to his brother Enos Ellmaker, who emigrated to Oregon Territory in 1853. Bound therewith is a genealogy of the Oelmachers beginning in 1652 and a short one of the Fisher family of Kentucky and Missouri. In addition is a most interesting "Autobiography" of Enos Ellmaker, edited by his son, Amos. Pictures of Reuben Ellmaker, writer of the Letters and of Enos and wife Elizabeth Fisher Ellmaker are included.

Samuel Handsaker: Autobiography, Diary, Reminiscences, 1853. Includes autobiographical sketch published in Pioneer Life, 1908; diary, 1853, from the Alton (Ill.) Telegraph; Reminiscences of Rogue River War; Pioneers of Umpqua ... An anecdote.

McClure, John Hamilton: How We Came To Oregon - Narrative Poem. (Includes History of the Bruce Family, written by Major William Bruce.)

Journal of Catherine Amanda Stansbury Washburn - Iowa to Oregon in 1853.

Eakin, Stewart Bates, Jr. A Short Sketch of a Trip Across the Plains by S. B. Eakin and Family 1866.

Goltra, Elizabeth J. Journal of Her Travels Across the Plains in the Year 1853.

Woodworth, James. Across the Plains to California in 1853.

- Collection Overview

- Collection Summary

- Information for Researchers

- Scope and Content

Masks required in Abakanowicz Research Center; optional for rest of Museum MORE

- Join & Give

The Pioneer: The Little Locomotive That Could

In October 1848, a small group of Chicagoans witnessed the Pioneer locomotive’s inaugural run as it pulled from the city’s first railway station. CHM director of exhibitions Paul Durica writes about the winding journey it took to find its way to the Chicago History Museum.

The Pioneer locomotive endures as the historical artifact that could. Despite often being overshadowed by larger and more dynamic objects, it has managed to appear (with some modifications to its appearance over the years) at every significant Chicago fair and festival from the 1880s through the 1940s, including both the 1893 World’s Columbian Exposition and the 1933–34 A Century of Progress International Exposition, before finding its forever home at the Chicago History Museum.

As the first locomotive to operate within the city, the Pioneer has long remained, in the words of one commentator, the “historic symbol of the coming of the railroads” to Chicago and the nation, transforming both in challenging and enduring ways. A small group of Chicagoans witnessed the Pioneer on its inaugural run as it pulled from the city’s first railway station, near the intersection of present-day Canal and Kinzie Streets, 175 years ago this October. Whether they regarded what they witnessed with optimism, skepticism, or some mix of the two was not recorded.

That first ride on the rails of the still-under-construction Galena and Chicago Union Railroad stretched as far as Des Plaines, Illinois, transporting a group of prominent citizens one way and the same group along with some grain, back to Chicago. Bought second-hand (though with no bill of sale, the origin of the Pioneer remains unknown; it was likely manufactured c. 1840 for an eastern railroad company), the Pioneer was replaced within a decade by bigger, faster, more powerful locomotives as first the Galena and Chicago Union and then other railroad lines expanded throughout the 1850s. As the Chicago Tribune described that first run a century later, this “little event in October 1848. . . was the forerunner of a mighty development that ultimately made Chicago the greatest railroad center in the world.”

In 1883 Chicago celebrated being the “center” of the railroad industry by hosting the National Exposition of Railway Appliances. One of the featured exhibits was the Pioneer , which had from about 1858 to 1874 been used solely for company and construction work and was now deteriorating in a train yard. Given a fresh coat of paint, its significance supported by the memories of retired engineers, the Pioneer had pride of place at the Exposition, but this was a prelude to the exposure it soon received at one of the most significant events in Chicago history.

This year marks the 130th anniversary of the World’s Columbian Exposition, the first Chicago world’s fair, an event invested in celebrating the past even as it looked toward the coming twentieth century. At the fair, in the Transportation Building designed by Louis Sullivan, the only one among the fourteen main structures not inspired by the classical past, stood that relic of Chicago, the Pioneer , “a funny-looking contrivance as compared with the great locomotives now in use,” according to the Tribune . There to tell its story was John Ebbert, who claimed to be its first engineer as well as an eyewitness to its arrival via the Great Lakes on the brig Buffalo . Ebbert’s stories of the early days of rail entertained visitors from around the world and established the Pioneer as an important symbol of this history. Today a variation of this experience at the World’s Columbian Exposition survives in an interactive display in the Museum’s Chicago: Crossroads of America exhibition.

From the World’s Columbian Exposition, the Pioneer embarked on a long, winding journey that would take it, among other places, to the Columbian Museum (today’s Field Museum), the 1904 Louisiana Purchase Exposition in St. Louis, A Century of Progress world’s fair, the Museum of Science and Industry, and the 1948 Chicago Railroad Fair.

It wouldn’t arrive at the Chicago Historical Society until 1972 and would, along with the 1892 L Car, become one of two large artifacts in Chicago: Crossroads of America when it opened in 2006.

There’s one small problem with this whole long story: the Pioneer visitors know may not have pioneered anything. The Pioneer isn’t named in any documents until 1856, when it appears in a Galena and Chicago Union inventory, and there were other locomotives in the company’s stock that fit the description of the one that first left the station in October 1848 (the exact date of which is somewhat disputed by historians). The Pioneer ’s history rests solely upon the reminisces of old railroad workers, first taken down in the 1880s and 1890s. “A bill of sale, a contemporary newspaper story, an old diary entry, any scrap dating back to October 1848 might settle the question,” writes John H. White in his survey of the documentary evidence surrounding the Pioneer from 1976. “Perhaps some industrious scholar will one day find the missing information.”

But perhaps having witnessed so much of the city’s history in the last 175 years, where this humble locomotive began its journey and whether it was the first really doesn’t matter anymore?

- “All Are of Interest: Exhibits to Be Seen in the Transportation Building,” Chicago Daily Tribune , April 30, 1893.

- Paul Angle, “Chicago’s First Railroad,” Chicago History , vol. 1, no. 12 (Summer 1948).

- Philip Hampson, “Chicago Railroad Fair Opens Today,” Chicago Daily Tribune , July 20, 1948.

- Patrick McLear, “The Galena and Chicago Union Railroad: A Symbol of Chicago’s Economic Maturity,” J ournal of the Illinois State Historical Society , vol. 73, no. 1 (Spring 1980).

- John H. White Jr., The Pioneer: Chicago’s First Locomotive (Chicago: Chicago Historical Society, 1976).

This is Paper 42 from the Smithsonian Institution United States National Museum Bulletin 240, comprising Papers 34-44, which will also be available as a complete e-book.

The front material, introduction and relevant index entries from the Bulletin are included in each single-paper e-book.

Underlined Figure numbers link to high resolution copies of selected images.

Corrections to typographical errors are underlined like this . Mouse over to view the original text.

SMITHSONIAN INSTITUTION UNITED STATES NATIONAL MUSEUM BULLETIN 240

SMITHSONIAN PRESS

MUSEUM OF HISTORY AND TECHNOLOGY

Contributions From the Museum of History and Technology

Papers 34-44 On Science and Technology

SMITHSONIAN INSTITUTION · WASHINGTON, D.C. 1966

Publications of the United States National Museum

The scholarly and scientific publications of the United States National Museum include two series, Proceedings of the United States National Museum and United States National Museum Bulletin .

In these series, the Museum publishes original articles and monographs dealing with the collections and work of its constituent museums—The Museum of Natural History and the Museum of History and Technology—setting forth newly acquired facts in the fields of anthropology, biology, history, geology, and technology. Copies of each publication are distributed to libraries, to cultural and scientific organizations, and to specialists and others interested in the different subjects.

The Proceedings , begun in 1878, are intended for the publication, in separate form, of shorter papers from the Museum of Natural History. These are gathered in volumes, octavo in size, with the publication date of each paper recorded in the table of contents of the volume.

In the Bulletin series, the first of which was issued in 1875, appear longer, separate publications consisting of monographs (occasionally in several parts) and volumes in which are collected works on related subjects. Bulletins are either octavo or quarto in size, depending on the needs of the presentation. Since 1902 papers relating to the botanical collections of the Museum of Natural History have been published in the Bulletin series under the heading Contributions from the United States National Herbarium , and since 1959, in Bulletins titled “Contributions from the Museum of History and Technology,” have been gathered shorter papers relating to the collections and research of that Museum.

The present collection of Contributions, Papers 34-44, comprises Bulletin 240. Each of these papers has been previously published in separate form. The year of publication is shown on the last page of each paper.

Frank A. Taylor Director, United States National Museum

Contributions from The Museum of History and Technology : Paper 42 The “ Pioneer ”: Light Passenger Locomotive of 1851 In the Museum of History and Technology

John H. White

THE CUMBERLAND VALLEY RAILROAD 244

SERVICE HISTORY OF THE “PIONEER” 249

MECHANICAL DESCRIPTION OF THE “PIONEER” 251

Figure 1.— The “ Pioneer ,” built in 1851 , shown here as renovated and exhibited in the Museum of History and Technology, 1964. In 1960 the locomotive was given to the Smithsonian Institution by the Pennsylvania Railroad through John S. Fair, Jr. (Smithsonian photo 63344B.)

[Pg 243] John H. White

The “PIONEER”: LIGHT PASSENGER LOCOMOTIVE of 1851 In the Museum of History and Technology

In the mid-nineteenth century there was a renewed interest in the light, single-axle locomotives which were proving so very successful for passenger traffic. These engines were built in limited number by nearly every well-known maker, and among the few remaining is the 6-wheel “Pioneer,” on display in the Museum of History and Technology, Smithsonian Institution. This locomotive is a true representation of a light passenger locomotive of 1851 and a historic relic of the mid-nineteenth century.

The Author : John H. White is associate curator of transportation in the Smithsonian Institution’s Museum of History and Technology.

The “Pioneer” is an unusual locomotive and on first inspection would seem to be imperfect for service on an American railroad of the 1850’s. This locomotive has only one pair of driving wheels and no truck, an arrangement which marks it as very different from the highly successful standard 8-wheel engine of this period. All six wheels of the Pioneer are rigidly attached to the frame. It is only half the size of an 8-wheel engine of 1851 and about the same size of the 4—2—0 so common in this country some 20 years earlier. Its general arrangement is that of the rigid English locomotive which had, years earlier, proven unsuitable for use on U.S. railroads.

These objections are more apparent than real, for the Pioneer , and other engines of the same design, proved eminently successful when used in the service for which they were built, that of light passenger traffic. The Pioneer’s rigid wheelbase is no problem, for when it is compared to that of an 8-wheel engine it is found to be about four feet less; and its small size is no problem when we realize it was not intended for heavy service. Figure 2, a diagram, is a comparison of the Pioneer and a standard 8-wheel locomotive.

Since the service life of the Pioneer was spent on the Cumberland Valley Railroad, a brief account of that line is necessary to an understanding of the service history of this locomotive.

Exhibits of the “Pioneer”

The Pioneer has been a historic relic since 1901. In the fall of that year minor repairs were made to the locomotive so that it might be used in the sesquicentennial celebration at Carlisle, Pennsylvania. On October 22, 1901, the engine was ready for service, but as it neared Carlisle a copper flue burst. The fire was extinguished and the Pioneer was pushed into town by another engine. In the twentieth century, the Pioneer was displayed at the Louisiana Purchase Exposition, St. Louis, Missouri, in 1904, and at the Wheeling, West Virginia, semicentennial in 1913. In 1927 it joined many other historic locomotives at the Baltimore and Ohio Railroad’s “Fair of the Iron Horse” which commemorated the first one hundred years of that company. From about 1913 to 1925 the Pioneer also appeared a number of times at the Apple-blossom Festival at Winchester, Virginia. In 1933-1934 it was displayed at the World’s Fair in Chicago, and in 1948 at the Railroad Fair in the same city. Between 1934 and March 1947 it was exhibited at the Franklin Institute, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania.

The Cumberland Valley Railroad

The Cumberland Valley Railroad (C.V.R.R.) was chartered on April 2, 1831, to connect the Susquehanna and Potomac Rivers by a railroad through the Cumberland Valley in south-central Pennsylvania. The Cumberland Valley, with its rich farmland and iron-ore deposits, was a natural north-south route long used as a portage between these two rivers. Construction began in 1836, and because of the level valley some 52 miles of line was completed between Harrisburg and Chambersburg by November 16, 1837. In 1860, by way of the Franklin Railroad, the line extended to Hagerstown, Maryland. It was not until 1871 that the Cumberland Valley Railroad reached its projected southern terminus, the Potomac River, by extending to Powells Bend, Maryland. Winchester, Virginia, was entered in 1890 giving the Cumberland Valley Railroad about 165 miles of line. The railroad which had become associated with the Pennsylvania Railroad in 1859, was merged with that company in 1919.

By 1849 the Cumberland Valley Railroad was in poor condition; the strap-rail track was worn out and new locomotives were needed. Captain Daniel Tyler was hired to supervise rebuilding the line with T-rail, and easy grades and curves. Tyler recommended that a young friend of his, Alba F. Smith, be put in charge of modernizing and acquiring new equipment. Smith recommended to the railroad’s Board of Managers on June 25, 1851, that “much lighter engines than those now in use may be substituted for the passenger transportation and thereby effect a great saving both in point of fuel and road repairs....” [1] Smith may well have gone on to explain that the road was operating 3- and 4-car passenger trains with a locomotive weighing about 20 tons; the total weight was about 75 tons, equalling the uneconomical deadweight of 1200 pounds per passenger. Since speed was not an important consideration (30 mph being a good average), the use of lighter engines would improve the deadweight-to-passenger ratio and would not result in a slower schedule.

The Board of Managers agreed with Smith’s recommendations and instructed him “... to examine the two locomotives lately built by Mr. Wilmarth and now in the [protection?] of Captain Tyler at Norwich and if in his judgment they are adequate to our wants ... have them forwarded to the road.” [2] Smith inspected the locomotives not long after this resolution was passed, for they were on the road by the time he made the following report [3] to the Board on September 24, 1851:

In accordance with a resolution passed at the last meeting of your body relative to the small engines built by Mr. Wilmarth I proceeded to Norwich to make trial of their capacity—fitness or suitability to the Passenger transportation of our Road—and after as thorough a trial as circumstances would admit (being on another Road than our own) I became satisfied that with some necessary improvements which would not be expensive (and are now being made at our shop) [Pg 245] the engines would do the business of our Road not only in a manner satisfactory in point of speed and certainty but with greater ultimate economy in Expenses than has before been practised in this Country.

Figure 2. — Diagram comparing the Pioneer (shaded drawing) with the Columbia , a standard 8-wheel engine of 1851. (Drawing by J. H. White.)

After making the above trial of the Engines—I stated to your Hon. President the result of the trial—with my opinion of their Capacity to carry our passenger trains at the speed required which was decidedly in favor of the ability of the Engines. He accordingly agreed that the Engines should at once be forwarded to the Road in compliance with the Resolution of your Board. I immediately ordered the Engines shipped at the most favorable rates. They came to our Road safely in the Condition in which they were shipped. One of the Engines has been placed on the Road and I believe performed in such a manner as to convince all who are able to judge of this ability to perform—although the maximum duty of the Engines was not performed on account of some original defects which are now being remedied as I before stated.

Within ten days the Engine will be able to run regularly with a train on the Road where in shall be enabled to judge correctly of their merits.

An accident occurred during the trial of the Small Engine at Norwich which caused a damage of about $300 in which condition the Engine came here and is now being repaired—the cost of which will be presented to your Board hereafter. As to the fault or blame of parties connected with the accident as also the question of responsibility for Repairs are questions for your disposal. I therefore leave the matter until further called upon.

The Expenses necessarily incurred by the trial of the Engines and also the Expenses of transporting the same are not included in the Statement herewith presented, the whole amount of which will not probably exceed $400.00.

These two locomotives became the Cumberland Valley Railroad’s Pioneer (number 13) and Jenny Lind (number 14). While Smith notes that one of the engines was damaged during the inspection trials, Joseph Winters, an employee of the Cumberland Valley who claimed he was accompanying the engine enroute to Chambersburg at the time of their delivery, later recalled that both engines were damaged in transit. [4] According to Winters a train ran into the rear of the Jenny Lind , damaging both it and the Pioneer , the accident occurring near Middletown, Pennsylvania. The Jenny Lind was repaired at Harrisburg but the Pioneer , less seriously damaged, was taken for repairs to the main shops of the Cumberland Valley road at Chambersburg.

Figure 3.—“ Pioneer ,” about 1901 , showing the sandbox and large headlamp. Note the lamp on the cab roof, now used as the headlight. (Smithsonian photo 49272.)

While there seems little question that these locomotives were not built as a direct order for the Cumberland Valley Railroad, an article [5] appearing in the Railroad Advocate in 1855 credits their design to Smith. The article speaks of a 2—2—4 built for the Macon and Western Railroad and says in part:

This engine is designed and built very generally upon the ideas, embodied in some small tank engines designed by A. F. Smith, Esq., for the Cumberland Valley road. Mr. Smith is a strong advocate of light engines, and his novel style and proportions of engines, as built for him a few years since, by Seth Wilmarth, at Boston, are known to some of our readers. Without knowing all the circumstances under which these engines are worked on the Cumberland Valley road, we should not venture to repeat all that we have heard of their performances, it is enough to say that they are said to do more, in proportion to their weight, than any other engines now in use.

The author believes that the Railroad Advocate’s claim of Smith’s design of the Pioneer has been confused with his design of the Utility (figs. 6, 7). Smith designed this compensating-lever engine to haul trains over the C.V.R.R. bridge at Harrisburg. It was built by Wilmarth in 1854.

Figure 4. — Map of the Cumberland Valley Railroad as it appeared in 1919.

Figure 5.— An early broadside of the Cumberland Valley Railroad.

According to statements of Smith and the Board of Managers quoted on page 244, the Pioneer and the Jenny Lind were not new when purchased from their maker, Seth Wilmarth. Although of recent manufacture, previous to June 1851, they were apparently doing service on a road in Norwich, Connecticut. It [Pg 247] should be mentioned that both Smith and Tyler were formerly associated with the Norwich and Worcester Railroad and they probably learned of these two engines through this former association. It is possible that the engines were purchased from Wilmarth by the Cumberland Valley road, which had bought several other locomotives from Wilmarth in previous years. It was the practice of at least one other New England engine builder, the Taunton Locomotive Works, to manufacture engines on the speculation that a buyer would be found; if no immediate buyers appeared the engine was leased to a local road until a sale was made. [6]

Regarding the Jenny Lind and Pioneer , Smith reported [7] to the Board of Managers at their meeting of March 17, 1852:

The small tank engines which were purchased last year ... and which I spoke in a former report as undergoing at that time some necessary improvements have since that time been fairly tested as to their capacity to run our passenger trains and proved to be equal to the duty.

The improvements proposed to be made have been completed only on one engine [ Jenny Lind ] which is now running regularly with passenger trains—the cost of repairs and improvements on this engine (this being the one accidentally broken on the trial) amounted to $476.51. The other engine is now in the shop, not yet ready for service but will be at an early day.

Figure 6.— The “ Utility ” as rebuilt to an 8-wheel engine , about 1863 or 1864. It was purchased by the Carlisle Manufacturing Co. in 1882 and was last used in 1896. (Smithsonian photo 36716F.)

Figure 7.— The “ Utility ,” designed by Smith A. F. and constructed by Seth Wilmarth in 1854, was built to haul trains across the bridge at Harrisburg, Pa.

Figure 8.— The earliest known illustration of the Pioneer , drawn by A. S. Hull, master mechanic of the Cumberland Valley Railroad in 1876. It depicts the engine as it appeared in 1871. ( Courtesy of Paul Westhaeffer. )

The Pioneer and Jenny Lind achieved such success in action that the president of the road, Frederick Watts, commented on their performance in the annual report of the Cumberland Valley Railroad for 1851. Watts stated that since their passenger trains were rarely more than a baggage car and two coaches, the light locomotives “... have been found to be admirably adapted to our business.” The Cumberland Valley Railroad, therefore, added two more locomotives of similar design in the next few years. These engines were the Boston and the Enterprise , also built by Wilmarth in 1854-1855.

Watts reported the Pioneer and Jenny Lind cost $7,642. A standard 8-wheel engine cost about $6,500 to $8,000 each during this period. In recent years, the Pennsylvania Railroad has stated the Pioneer cost $6,200 in gold, but is unable to give the source for this information. The author can discount this statement for it does not seem reasonable that a light, cheap engine of the pattern of the Pioneer could cost as much as a machine nearly twice its size.

Figure 9.— Annual pass of the Cumberland Valley Railroad issued in 1863.

Figure 10. — Timetable of the Cumberland Valley Railroad for 1878.

Service History of the Pioneer

After being put in service, the Pioneer continued to perform well and was credited as able to move a 4-car passenger train along smartly at 40 mph. [8] This tranquility was shattered in October 1862 by a raiding party led by Confederate General J. E. B. Stuart which [Pg 251] burned the Chambersburg shops of the Cumberland Valley Railroad. The Pioneer , Jenny Lind , and Utility were partially destroyed. The Cumberland Valley Railroad in its report for 1862 stated:

The Wood-shop, Machine-shop, Black-smith-shop, Engine-house, Wood-sheds, and Passenger Depot were totally consumed, and with the Engine-house three second-class Engines were much injured by the fire, but not so destroyed but that they may be restored to usefulness.

However, no record can be found of the extent or exact nature of the damage. The shops and a number of cars were burned so it is reasonable to assume that the cab and other wooden parts of the locomotive were damaged. One unverified report in the files of the Pennsylvania Railroad states that part of the roof and brick wall fell on the Pioneer during the fire causing considerable damage. In June 1864 the Chambersburg shops were again burned by the Confederates, but on this occasion the railroad managed to remove all its locomotives before the raid. During the Civil War, the Cumberland Valley Railroad was obliged to operate longer passenger trains to satisfy the enlarged traffic. The Pioneer and its sister single-axle engines were found too light for these trains and were used only on work and special trains. Reference to table 1 will show that the mileage of the Pioneer fell off sharply for the years 1860-1865.

Table 1.—Yearly Mileage of the Pioneer (From Annual Reports of the Cumberland Valley Railroad)

[a] Mileage 1852 for January to September (no record of mileage recorded in Annual Reports previous to 1852).

[b] 15,000 to 20,000 miles per year was considered very high mileage for a locomotive of the 1850’s.

[c] No mileage reported for any engines due to fire.

[d] Not listed on roster.

[e] The Pennsylvania Railroad claims a total mileage of 255,675. This may be accounted for by records of mileages for 1862, 1870, and 1879.

In 1871 the Pioneer was remodeled by A. S. Hull, master mechanic of the railroad. The exact nature of the alterations cannot be determined, as no drawings or photographs of the engine previous to this time are known to exist. In fact, the drawing (fig. 8) prepared by Hull in 1876 to show the engine as remodeled in 1871 is the oldest known illustration of the Pioneer . Paul Westhaeffer, a lifelong student of Cumberland Valley R. R. history, states that according to an interview with one of Hull’s descendants the only alteration made to the Pioneer during the 1871 “remodeling” was the addition of a handbrake. The road’s annual report of 1853 describes the Pioneer as a six-wheel tank engine. The report of 1854 mentions that the Pioneer used link motion. These statements are enough to give substance to the idea that the basic arrangement has survived unaltered and that it has not been extensively rebuilt, as was the Jenny Lind in 1878.

By the 1870’s, the Pioneer was too light for the heavier cars then in use and by 1880 it had reached the end of its usefulness for regular service. After nearly thirty years on the road it had run 255,675 miles. Two new passenger locomotives were purchased in 1880 to handle the heavier trains. In 1881 the Pioneer was dropped from the roster, but was used until about 1890 for work trains. After this time it was stored in a shed at Falling Spring, Pennsylvania, near the Chambersburg yards of the C.V.R.R.

Mechanical Description of the Pioneer

Figure 11.—“ Pioneer ,” about 1901 , scene unknown. ( Photo courtesy of Thomas Norrell. )

After the early 1840’s the single-axle locomotive, having one pair of driving wheels, was largely [Pg 252] superseded by the 8-wheel engine. The desire to operate longer trains and the need for engines of greater traction to overcome the steep grades of American roads called for coupled driving wheels and machines of greater weight than the 4—2—0. After the introduction of the 4—4—0, the single-axle engine received little attention in this country except for light service or such special tasks as inspection or dummy engines.