Europe Chevron

Iceland Chevron

How Iceland Is Rethinking Tourism for the Long Haul

By Julia Eskins

Iceland has a New Year’s resolution. After a 10-month pause in tourism due to global lockdowns, the country is preparing for a new era of outdoor adventure—one that locals are hoping is more sustainable than before.

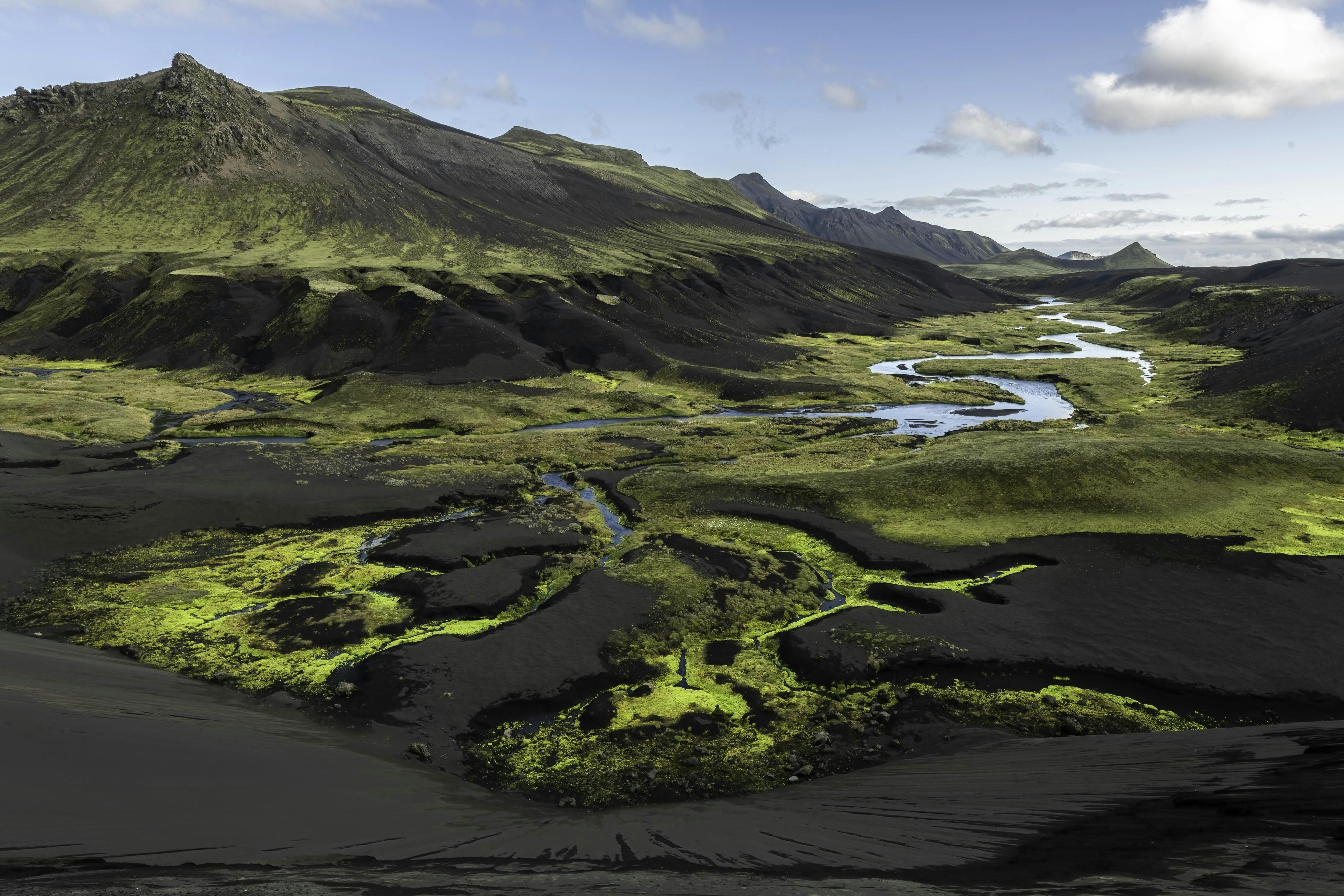

The Nordic island nation’s meteoric rise in popularity remains a controversial topic. Once named the fastest-growing destination in Europe, its economy has become reliant on flashpackers keen to marvel at glaciers, geysers, and green-streaked skies. But environmentalists have raised concerns about the impact of overtourism on delicate ecosystems. Iceland’s answer? Encourage people to stay longer, travel slower , and make use of the country’s greatest asset in a COVID-minded world: space.

Similar to other hot-ticket destinations like Venice and Amsterdam , which celebrated reduced pollution in 2020, Iceland experienced its own silver linings in a year of fewer visitors. Thingvellir National Park director Einar Sæmundsen noticed less litter on trails that were previously trampled by hikers. Meanwhile, locals enjoyed the quietude, with domestic travelers flocking to beloved sites, as well as the Westfjords and Eastfjords—two lesser-explored regions that are finally getting the attention and financial support from the Icelandic government to thrive.

“The growth we saw in the number of visitors up to 2019 was far too rapid and we were getting close to the edge of seriously unsustainable development,” says Tryggvi Felixson, a tour guide and Chair of Landvernd, the Icelandic Environment Association. “We are fortunate that Iceland is a relatively big country. It’s possible to distribute the traffic more evenly than we have done before.”

Iceland's national parks, like Thingvellir, pictured, have seen benefits from less foot traffic during the pandemic.

More funding for infrastructure and conservation

Unlike destinations that tightened budgets in 2020, Iceland increased its spending on tourism by 40 percent. A substantial amount of the $1.73 billion ISK ($13.6 million) budget was used to improve infrastructure at tourist sites. Many of these places, like the basalt column-flanked canyon of Stuðlagil, became famous due to social media. The government is finally playing catch-up to build necessities like restrooms, parking lots, designated trails, and wheelchair-accessible entrances.

“It’s been challenging to stay ahead of social media,” says Skarphéðinn Berg Steinarsson, Director General of the Icelandic Tourist Board. “Visitors like to go around wherever they want and that's how we want to keep it. But we are sometimes unprepared for the sites they're visiting. Many of these places are much more delicate during the winter and spring when the frost is leaving the soil. A lot of traffic can spoil the environment.”

Iceland’s parliament is also now debating a proposal to establish a national park in the Highlands, which will cover and protect about 30 percent of the country, says Felixson.

A push for longer stays, alternative routes, and remote accommodations

Inexpensive flights once made Iceland a magnet for weekend jaunts, but with COVID-19, longer trips that include working remotely are becoming the norm. In November, Iceland announced a new visa for international remote workers. Foreign nationals, including Americans, are now eligible to stay in Iceland for up to six months, as long as they are employed with a company or can verify self-employment. Unlike other visas aimed at digital nomads, Iceland’s program has some important fine print. Your monthly salary must be at least 1 million ISK ($7,360) or about $88,000 per year to qualify.

The quality-over-quantity strategy is simple: attract high-earning professionals that can help stimulate the local economy without leading to overcrowding. The new visa program is just one aspect of Iceland’s shift toward attracting those craving a slower style of exploration.

“Not everyone has to drive the Ring Road,” says Steinarsson. “We’re encouraging people to travel around the country but, preferably, stay longer in each region.”

Offering alternatives to Route 1, which follows the circumference of the island, Iceland opened two new circuits in late 2020. One is the Westfjords Way, a 590-mile journey around the Westfjords peninsula, which was previously closed in the winter due to avalanche risks. The second new route is the Diamond Circle in North Iceland, a 155-mile circuit replete with waterfalls and wildlife.

The Sky Lagoon, one of the biggest tourism projects in Icelandic history, is set to launch in the spring.

Alex Erdekian

CNT Editors

Jesse Ashlock

Charlie Hobbs

But that isn’t to say the capital should be completely overlooked. This spring, new geothermal spa The Sky Lagoon is set to open in Reykjavik . The project is one of the biggest in Icelandic tourism’s history at 4 billion ISK ($31 million). With its 260-foot oceanfront infinity pool and architecture inspired by the region’s traditional turf-houses, it could be an attractive alternative to the famous Blue Lagoon.

For those who want to experience nature away from the crowds, the newly launched Bubble Hotel offers the chance to sleep under the Northern Lights in one of 18 clear dome structures located in two remote forest locations. Meanwhile, close to Europe’s largest glacier in Vatnajökull National Park, the new Six Senses Össurá Valley is set to open in 2022. With 70 rooms and private cottages sprawled across 4,000 acres and built using renewable materials, the property will usher in a new option for sustainable luxury.

Conserving the environment while continuing to grow economically remains a challenge. But perhaps the forced pause has led to more than just a rebirth of quiet and clean trails. This time—with more remote adventures and better infrastructure—the land of ice and fire will be ready.

Recommended

Highland Base Kerlingarfjöll

Silica Hotel

Europe Travel Guide

By signing up you agree to our User Agreement (including the class action waiver and arbitration provisions ), our Privacy Policy & Cookie Statement and to receive marketing and account-related emails from Traveller. You can unsubscribe at any time. This site is protected by reCAPTCHA and the Google Privacy Policy and Terms of Service apply.

Search Arctic Today

After years of over-tourism concerns, iceland now has the opposite problem, while the tourism industry has been hard hit, icelanders aren't overly worried about its future..

COPENHAGEN — Icelanders seem to have found the best way to keep the island free of the coronavirus while welcoming tourists at the same time.

Arrivals reaching Keflavik airport, near Reykjavik, are offered coronavirus tests on landing. Priced at only $64-79, it enables them to avoid having to undergo a 14-day quarantine.

After that’s done with, everything is as it always was before the outbreak — the hotels, the restaurants and car rentals, says Sigridur Dogg Gudmundsdottir, who runs Visit Iceland, a tourism organization.

The great thing is how sparsely populated Iceland is, she says.

“With a population of 360,000 living on an island a third of the size of Germany, it’s emptier than any other country in Europe,” she says.

“It’s the perfect place for social distancing,” she says. “It’s really easy to enjoy being out in the countryside without running into loads of people.”

[ Iceland reports fewer visitors, longer stays in 2019 ]

Nonetheless, the tourism industry is concerned about the fallout of the pandemic and is adapting to attract domestic travellers too.

Before the outbreak of the coronavirus, only one in 10 tourists came from Iceland, but this is set to increase, says Gudmundsdottir.

She now sees that domestic travel is increasing — one of the few positive effects of the coronavirus outbreak.

“We suddenly travel our own country in greater numbers than before, and at the same time we discover what tourism has brought in terms of both services and infrastructure. It is good that we appreciate our country more.”

Her concern is founded on the sobering comparison that more than 120,000 people came to Iceland in April 2019 — which fell to 924 people the same month in 2020, as the pandemic ravaged Europe.

After years of steep growth, Iceland’s tourism industry has reached almost a standstill, a loss that could run into the billions.

[ Arctic tourism businesses fear they won’t survive the coronavirus crisis ]

But Icelanders are optimistic, even if most in Reykjavik realize that it will take a while to rebuild the numbers from the last few years.

The growth all started with Eyjafjallajokull erupting in 2010, putting the country on the map. By 2018, the country was welcoming 2.3 million visitors from abroad, up from an average of 500,000.

Icelanders were happy with the numbers in 2019 — a solid 2 million that everyone felt would be fine as a standard to ensure tourism to geysers, waterfalls and hot water sources stayed sustainable.

Then came the virus, the cancellations, the restrictions — and the number of passengers landing at Keflavik shrank to almost nil.

The 924 guests in April 2020 was around the same number as arrived in 1961, according to broadcaster RUV. May 2020 saw thin pickings too, with 1,035 travellers reportedly landing at the airport, a 99.2-percent fall compared to the same month a year before.

“Things were looking pretty good for 2020,” Gudmundsdottir says. There’s no way it can look like the previous years now, she adds.

As everywhere else, for those who own restaurants, hotels or tour operators, that has meant difficulties.

Iceland’s government is trying to help, allowing people to defer their taxes and dropping taxes on overnight stays for now.

But the damage is expected to be sizeable: In 2019, tourists from abroad spent some 383 billion krona ($2.8 billion). A year later, some 250 billion to 300 billion krona less is expected.

“We don’t know how many tourists will come to Iceland,” says Iceland’s Tourism Minister Thordis Kolbrun Gylfadottir.

Icelanders used to try and assess how many tourists could go to sights that are particularly popular without overwhelming them completely. “We were concerned about possible over-tourism in certain places. Now we’re more worried about under-tourism,” she says.

There is hope, particularly given that there have barely been any new infections among Icelanders in weeks.

Plus, people are starting to come back.

“This was a shock, but we know that we will be able to get back on our feet,” says Gylfadottir. What matters is that the situation improves elsewhere too, she says, like in the United States.

Iceland welcomes more tourists from the U.S. than any other nation.

Privacy Overview

Skip to content. | Skip to navigation

- Skandinavisk

- siteaction-1

- siteaction-2

- siteaction-3

Subscribe to the latest news from the Nordic Labour Journal by e-mail. The newsletter is issued 9 times a year. Subscription is free of charge.

Print current newsletter

- Iceland’s tourism becomes a hot environmental topic

Tourists drowning at sea. Tourists dying in bus accidents. Tourists driving illegally off road and getting stuck in the middle of an active geothermal area. They do serious damage to nature just to post pictures of themselves and their tyre tracks on social media.

“I did not know,” they say.

These are some of the problems which now face Iceland’s tourism industry. Icelandic nature is under threat, and there might be problems ahead. Tourism has brought new challenges to Iceland.

Rannveig Grétarsdóttir

“When our guests do not respect nature, it’s a negative thing. But it can also be good when other guests see our reactions and realise that bad behaviour will not be tolerated,” says Rannveig Grétarsdóttir, CEO of the whale safari company Elding in Reykjavik.

Iceland’s tourism boom has slowed somewhat since the Icelandic airline WOW’s bankruptcy in the spring. Last year, 2.7 million people visited the island, but that figure is expected to fall this year – partly because of Icelandic currency fluctuations, but mainly because fewer foreign airlines now fly there.

The fall in tourism numbers allows Iceland to think, according to Rannveig Grétarsdóttir. She believes it is important to use this time to develop rules and introduce regulations around visits to Iceland’s many natural attractions.

No future vision

Jón Björnsson, Chief Park Ranger for the Snæfellsjökull national park, says Iceland has lacked the infrastructure needed to accommodate all the guests who have been coming in recent years. He says Iceland’s natural resources have been exploited in an irresponsible way; tourist companies have only been focusing on growth and have failed to think about sustainability and the impact of tourism on the local population.

Jón Björnsson, Chi ef Park Ranger for the Snæfellsjökull national park. Photo: private

“There is still no future vision within the tourism sector. There is still a lack of knowledge, and in certain areas the locals are about to run out of patience,” says Björnsson.

People in general do understand how important tourism is to Iceland’s economy and to individual households, however.

“Tourism is sometimes bad for the quality of life, but at the same time it does bring in money, and the Icelandic people understand this,” he continues.

The Icelandic Association for Search and Rescue, ICE-SAR, believes foreign guests’ behaviour has changed. Project manager Jónas Guðmundsson says the number of accidents involving tourists has fallen, with the exception of 2018. But Iceland must continue to develop its infrastructure in order to control where foreign visitors go.

“Most visitors behave in a nice and rational manner, except for a small number of social media celebrities,” he says.

As part of its drive to teach tourists to be more responsible, the tourism agency Inspired by Iceland has published a video showing how to take selfies. It has already had more than half a million views.

“We have not had good infrastructure up until now, and so it has been very important for tourism operators to warn tourists and to control the traffic to various places,” he says.

Damage compensation

The Icelandic government has been given a wake-up call. A few years ago there were not enough national park wardens, but this has changed. Tourism authorities are working hard to strengthen regulations for how to protect and control traffic to various areas and how to issue fines if rules are broken.

Nature has suffered, but now there is at least a tool available for stopping problems from arising. Police can now demand compensation for damage resulting from illegal environmental activities.

“I expect us to handle illegal environmental activities far more strictly in future. The government has now understood how important this is,” says Jón Björnsson.

Guðmundur Ingi Guðbrandsson, the Minister for the Environment, thinks Iceland is now in control of tourism’s impact on nature. He says Iceland is investing in viewing spots, toilets and ladders in order to control the traffic and the way visitors interact with nature. The country will now make plans for how tourism and nature will coexist without having a negative impact on the environment. Then there will be a debate on whether the number of visitors to certain areas should be limited.

The climate issue is extremely important to Iceland, while air traffic remains important to Iceland’s largest industry – the tourism sector. The Minister for the Environment believes that the number of foreign visitors might fall, but that they will stay for longer periods of time. Many airlines are also offering CO2 compensation schemes.

“Air traffic represents a large proportion of the total tourism CO2 footprint. You cannot take a train to Iceland, so we are in a special situation,” he explains.

Reorganising air traffic

The government has already developed a climate policy. Iceland will always be dependent on planes to link to the rest of the world, but the idea is to make greater use of video conferencing in order to reduce the number of flights for civil servants, until the aircraft industry starts using more environmentally friendly fuels.

“People in general should also think about how necessary it is to travel abroad as often as they do, or whether it might be possible to combine two journeys into one,” says Guðmundur Ingi.

Rannveig at Elding whale safari thinks Icelanders have not been treating nature all that well in the past, but that people are now ready to change the way they think and act. That is why they react so strongly when foreign guests fail to treat nature with respect. She believes that Iceland still has a long list of things that must be done in order to strengthen Iceland as a tourist destination.

“Icelanders are ready to introduce sustainability into the way we treat nature, but we must act faster,” says Rannveig Grétarsdóttir. She proposes to present to the Icelandic population an overview of what the tourism industry entails, to help Icelanders better understand what tourism is all about.

We will be focusing on nature

The tourism boom became a tsunami that engulfed Iceland. There was an uncontrolled flow of tourists, and the population was not prepared for so many guests. Icelanders started feeling the tourists were in their way. Now that tourism is abating, the government and the people can focus on sustainability, waste recycling and making sure the tourism industry uses renewable energy.

Rannveig Grétarsdóttir believes it is necessary to unite the people in the fight to save the environment, while also achieving a balanced understanding of the tourism industry’s needs.

“In the whale safari business, we always look at how we can develop for the future. We still have to use diesel-powered boats, at least for a while longer. In the meantime we can work on other ways of limiting our company’s impact on nature,” explains Rannveig.

“There are so many things we Icelanders can improve on and work with,” she says.

Icelandic tourism authorities are trying to make tourists take the Icelandic Pledge – with this humouristic list:

- Sustainable tourism in Åland – no Coca-Cola or Norwegian salmon

- Åland: many travellers, far fewer overnighters

- Is overtourism a threat to the Nordics, or can the sector become sustainable?

- Closing down the Faroes to attract more tourists

Receive Nordic Labour Journal's newsletter nine times a year. It's free.

Work Research Institute OsloMet – Oslo Metropolitan University, Postboks 4 St. Olavs plass, NO-0130 Oslo

The Nordic Council of Ministers is not responsible for the content

Filed under:

My own private Iceland

Tourism has never been “authentic.”

/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_image/image/65514762/Vox_tourism_iceland_084.0.jpg)

Share this story

- Share this on Facebook

- Share this on Twitter

- Share this on Reddit

- Share All sharing options

Share All sharing options for: My own private Iceland

There’s a place in Iceland where you can see the northern lights any time of year, regardless of the weather. You don’t have to ride a snowmobile into the mountains or rent a glass-roofed igloo. You don’t even need a winter jacket.

Leaning back in my recliner, I gaze upward at the ethereal reds, greens, and blues arcing across the sky, wavering like alien signals, an extraterrestrial message that we don’t know how to decode. I’m struck by their closeness. The bands of color appear right above me, like I could reach out and pass my hand through them.

These northern lights are glowing at 1 p.m. on an 8K resolution screen inside a well-heated IMAX planetarium at Perlan, a natural history museum set on a hill above downtown Reykjavik. Every hour on the hour the planetarium plays Áróra , a 22-minute-long documentary with footage of the lights taken from all over Iceland. The screen’s pixel density is so high that it runs up against the limits of what the human eye can perceive. The digital image might be clearer than reality. It’s definitely more convenient. All you need is a $20 ticket.

Places like Perlan — magnets for visitors and secondary representations of the country’s natural charms — are increasingly a necessity for Iceland, which in recent years has become synonymous with the term “overtourism.” Overtourism is what happens to a place when an avalanche of tourists “changes the quality of life for people who actually live there,” says Andrew Sheivachman, an editor at the travel website Skift, whose 2016 report about Iceland established the term. In other words, Sheivachman says, “a place becomes mainstream.” Iceland has about 300,000 residents, but it received more than 2.3 million overnight visitors last year. Tourists have flooded the island, crashing their camper vans in the wilderness, pooping in the streets of Reykjavik, and eroding the scenic canyon Fjaðrárgljúfur, where Justin Bieber shot a music video in 2015, forcing it to close temporarily. No wonder the museum is safer.

Overtourism also comes with a kind of stigma signified by that word “mainstream.” A reputation for excessive crowds means the tastemaking travel elite actually start avoiding a place, like a too-popular restaurant. “The early-adopter travelers are already onto the next cool, cheap, relatively intact place,” Sheivachman says. Since the Skift article, the term has been widely applied to places like Barcelona, Venice, and Tulum to suggest that no one who’s in the know would want to go there anymore.

:no_upscale()/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/19275950/Vox_tourism_iceland_054.jpg)

Such is the case with Iceland. From 2013 to 2017 the country saw tourist numbers rising more than 20 percent annually, but in 2018 and for projections into the near future, it looks more like 5 percent. There’s a sense that the tourists took all the Instagrams of waterfalls and glaciers they wanted and then left, leaving the Icelandic economy vulnerable. In 2017, 42 percent of the country’s export revenue was tourism, meaning that Iceland’s biggest product, larger than its fishing and aluminum industries, is itself. There are both too many tourists and not enough; Wow Air, one of the major conduits of Icelandic tourism, declared bankruptcy in March after an unsustainable expansion.

While traveling in Iceland this spring to talk to Icelanders about the boom and subsequent slowdown, however, I began to doubt the concept of overtourism itself. The stigma of overtourism is contingent on the sense that a place without as many tourists is more real, more authentic, than it is with them. It poses tourists as foreign entities to a place in the same way that viruses are foreign to the human body. From the visitor’s side, overtourism is also a subjective concern based on a feeling: It’s the point at which your personal narrative of unique experience is broken, the point at which there are too many people — like yourself — who don’t belong in a place.

There are more tourists now than ever before: The World Tourism Organization counted 1.4 billion international tourists in 2018 and predicts 1.8 billion by 2030. In terms of creating new tourists, developing countries are growing the fastest. Even the Icelandic “collapse,” as Bloomberg described it , seems to be more of a pause; Wow Air plans to relaunch late this year. If fully one-fifth of humanity are traveling away from home, then how foreign are tourists, after all? Tourism is not a localized phenomenon that we encounter in crowded piazzas and then leave but an omnipresent condition, like climate change or the internet, that we inhabit all the time. Maybe we need to accept it.

Watching Áróra in Perlan’s theater, I sit in the dark surrounded by empty seats while a disembodied female narrator with an Icelandic accent explains how the various colors of the northern lights come from the vibrations of different atmospheric gases hit by electrons. It strikes me that it doesn’t matter that I’m not seeing the actual northern lights; the season ended just before my arrival anyway. I am here in Iceland — surely that makes it a little more real than seeing it in New York? And besides, I’m not damaging any glaciers or emitting gas fumes. In the era of overtourism, the digital display isn’t just responsible. It’s authentic.

Iceland might be the modern symbol of overtourism, but it was hardly the first or only victim of tourists. The tradition of the Grand Tour started around the 17th century: British nobility would take a spin around the classical sites of the European continent after university, before settling down. Hordes of young men traipsed through Italy, returning with oil portraits of themselves amid castles or ruins to document the journey for their friends back home. In a journal published in 1766 , the Scottish author Tobias Smollett complained of carriages packed with travelers on the Tour route: You “run the risk of being stifled among very indifferent company.” In Rome, Smollett also observed his compatriots acting badly:

“[A] number of raw boys, whom Britain seemed to have poured forth on purpose to bring her national character into contempt: ignorant, petulant, rash, and profligate without any knowledge or experience of their own.”

It’s an 18th-century description of overtourism that’s still applicable today. But now the scale is vast and extreme, a hyperobject of loutishness enabled by cheap flights and social media. Tourists seem to be ruining tourism everywhere. Geographical places have been reduced to disposable trends.

:no_upscale()/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/19275969/Vox_tourism_iceland_107.jpg)

Over the past year, headlines have presented a litany of the absurd ways that we’re wrecking the places we attempt to appreciate. Indonesia’s Komodo Island considered closing because people keep stealing the lizards; Greece’s Santorini posted signs asking visiting Instagrammers to stop trespassing on scenic rooftops; selfie-takers ruined fields of tulips in the Netherlands as well as California’s poppy super bloom ; and Peru instituted timed tickets to Machu Picchu to stop the archaeological site from being trampled into nonexistence.

The crowds can even cause a kind of overtourism rage. Last year, two visitors beat each other up trying to take photos at Rome’s Trevi fountain and local protestors stormed a tourist bus in Barcelona, agitating against the invasion of the city by travelers. Venice, the most tragic victim of overtourism, recently instituted a new entrance tax to compensate for the damage the sinking city suffers; each visitor requires a daily fee of €3 to €10, depending on the expected traffic.

The pace of tourism fads also seems to have accelerated. One year the popular place to go is Berlin, the next it’s Iceland, then Lisbon, Bali, Mexico City, Dubrovnik, or Athens. Suddenly everyone is Instagramming from the same place, reproducing the same cliche images . In part, the speed is because of media, both print and digital. Travel and lifestyle magazines have long sold the dream of the next hot destination, from Conde Nast Traveler and Travel + Leisure to GQ , Vogue , and Monocle . The New York Times’ “ 36 Hours In… ” and “ 52 Places to Go ” series instantly become #goals. Guides published by Eater (also owned by Vox Media), Goop , and the content farm Culture Trip occupy online search results.

These tips expire quickly in the age of overtourism; you have to follow them while the spots are still semi-obscure in order to cash in your cultural capital — before they’re pictured on Tinder profiles above the words “Travel is my life.” Tourism is competitive. “The places where the magazine editors go, they’re quick to turn them into something, then quick to declare them over,” says Colin James Nagy, head of strategy at the agency Fred & Farid and a travel tastemaker himself. “In Tulum, that happened in five years.” New York magazine declared the Mexican beach town “dead” in February 2019. Nagy suggests instead Denmark’s Faroe Islands, Todos Santos in Mexico, and Dakar, Senegal, as up-and-comers. No doubt they’ll be deemed dead soon, too.

The ephemeral trendiness — travel as fast fashion — is part of a structural change in the tourism industry, according to Stanislav Ivanov, professor of tourism economics at Bulgaria’s Varna University of Management. Centuries ago, Grand Tour trips would take up to three years; you could stay in Rome for six to eight weeks alone. In the 20th century, traditional travel agents and tour operators offered pre-packaged trips that encouraged a sense of loyalty to particular places or hospitality brands, which tourists would return to repeatedly. There was less variety and more consistency. But since the 2000s, any traveler can easily use an “online travel agency,” or OTA, like Expedia or Booking.com and visit a new place every holiday. “People are collecting destinations,” Ivanov says. “Loyalty is not toward the hotels or destinations but toward the distributors.”

Plug in your travel dates and an OTA will serve you a long list of possible flights from various carriers, plus bonus car and hotel rentals and activity suggestions. OTAs were once cheaper and considerably smoother than direct booking; many companies have since upgraded their digital services, but the preference for OTAs remains. In the end, the service is less personalized and more automated.

Operating at a massive scale with call centers full of staff who may not know much about a traveler’s destination, OTAs end up serving the same itineraries over and over, according to Skarphéðinn Berg Steinarsson, the director-general of the Icelandic Tourism Board and a vehement critic of the digital platforms. They create what he calls a “top 10” list effect, reducing a country or city to a series of boxes to check off. OTAs “don’t give a damn about what’s really happening” in a place, Steinarsson says. “They are just shoveling out packages.”

:no_upscale()/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/19275988/Vox_tourism_iceland_024.jpg)

The problem is particularly acute in Iceland because so much of its tourism is routed through packaged bus trips; charting your own route with a rental car is both more expensive and more forbidding due to the weather, terrain, and not-insignificant chance of, say, getting stuck in a river . So visitors are most likely to succumb to convenience and take a spin around the Golden Circle, a 190-mile loop through the southern uplands that features the geysers, waterfalls, and rocky cliffs that everyone posts on Instagram or Facebook — the same spots that are sustaining the most damage. “If you go to Iceland, you have to do that list. ‘Go onto our site, it’s on the front screen, just take out your credit card, pay, get it over with, and start enjoying,’” Steinarsson says. “How deep do you have to dig before you start seeing places that would really be something special?”

Where we go and how we get there are increasingly influenced by a series of digital platforms — not just big OTAs, but Airbnb, Yelp, and Instagram — that prioritize engagement over originality. Overtourism is a consequence, not a cause. The more often a particular destination or package proves successful, the more users a site’s algorithm will drive to it, intensifying the problem by pushing travelers to have the same experiences as one another on a single beaten track around the globe, updated and optimized in real time. When one spot gets too crowded and its novelty used up, the next is slotted into its place.

For my trip, I decide to take the path of least resistance, relying on OTAs and recommendation sites to tell me exactly what to do — a tourist experience as well as an experience of tourism. It is indeed frictionless. I book an apartment in downtown Reykjavik through Airbnb and day-trips through Arctic Adventures, a local OTA. I buy tickets for a tour of Game of Thrones shooting locations and a day-long Golden Circle trip that hits all the main spectacles. Every activity seems to be rated 4.5 stars out of 5 or above. Weeks before my Icelandair flight, I’m algorithmically bombarded on YouTube by hypnotic pre-roll ads for the northern lights.

On the plane, I’m forced to watch a three-minute trailer for Iceland before I can even access the entertainment system. The flight map shows me why the country is such a tourism target. The frozen ovoid island is like a period in a chain of ellipses linking North America to the United Kingdom, Europe, and Scandinavia, making it a perfect stopover point. Iceland has no native inhabitants; in a sense, everyone has been a tourist since Norwegian and Swedish Viking sailors started accidentally landing there in the ninth century and settled when they found out the summer wasn’t so bad. Anything that exists on the island is a result of its visitors, making it difficult to determine where the “real” Iceland ends and where tourism begins.

:no_upscale()/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/19276013/Vox_tourism_iceland_090.jpg)

Almost every flight passes through Keflavik airport outside Reykjavik, by far the largest city, which functions like a fire hose, spitting out tourists. Icelandair has been offering free layovers through Keflavik since 1955 but only began marketing them aggressively in 1996 as it added destinations in North America, branding the country as a quick drop-in. The 2000s brought marketing campaigns including one with the euphemistic slogan “ Fancy a dirty weekend in Iceland? ” showing a photo of a couple with geothermal-bath mud on their faces.

In 2008, the financial crisis sunk Iceland’s previously expensive currency, which was terrible for Icelanders but great for tourism — the income from added visitors sped up economic recovery. “People were flocking there because it has a very high standard of living, it’s very beautiful, and now you could get it for one-third of the price,” Michael Raucheisen, Icelandair’s US-based communications manager for North America, tells me. Raucheisen, who flew Icelandair with his German father as a child, has worked at the company for two decades. “Nineteen years ago, people had no idea where Iceland was,” he says. “They thought Icelandair was an air-conditioning company.”

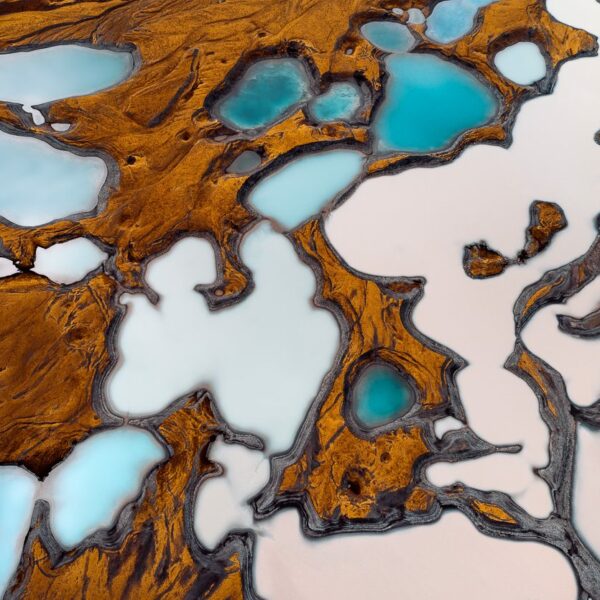

Iceland is also located on the Mid-Atlantic Ridge, the crack between the North American and Eurasian tectonic plates, making it one of the most volcanic spots on earth. Beginning in the early 1900s, Icelanders harnessed this energy as geothermal and hydropower for heat and electricity, making it much more comfortable than in chilly centuries past. Ninety-nine percent of the primary energy use in Iceland now comes from local renewable sources. The countryside is dotted with natural hot springs and futuristic power plants, all gently leaking steam. The place is a planetary Juul. (Reykjavik’s name, given in 874, means “smoke cove.”)

A volcano was in fact the biggest spark for the tourism boom. In April 2010, Eyjafjallajökull erupted, grounding more European flights than at any time since World War II, though in Iceland its impact was limited to the evacuation of a few farms and about 800 people . The eruption put maps and videos of Iceland on primetime TV news around the world, which amounted to free advertising. “Even during the volcano, the rest of Iceland was clean and beautiful. It was like, ‘Oh, it’s there, I didn’t know that,’” says Inga Hlín Pálsdóttir, the cheerful director of the tourism initiative Visit Iceland. The eruption happened, by chance, just as Pálsdóttir was helping to launch the country’s biggest tourism marketing push yet. “It was basically crisis communication,” she says. Several weeks of her life blurred together, but the campaign succeeded.

Iceland became a year-round destination, not just the warm months. Summer had been peak season; now, more tourists come for winter and the “shoulder seasons” between peak and off-peak, thanks in part to marketing campaigns highlighting the northern lights, festivals, and outdoor activities. American tourists gradually surpassed the German and French groups that traditionally came for long hiking trips. Tourists from Asia are now the fastest-growing demographic.

My first stop after Keflavik is the Blue Lagoon, a short, sparsely filled bus ride away. It’s recognizable from photos: a luminous pool of bright-blue water, like an aqueous latte, set amid jagged black volcanic rocks. But rather than the idyllic natural hot spring it resembles on Instagram, it’s actually a kind of giant artificial bathtub filled with wastewater from a nearby geothermal power plant. The Svartsengi power plant opened in 1976 and its superheated liquid and steam bubbled up through the surrounding lava field; one psoriasis patient bathed in it and saw an improvement and thus a business began.

Blue Lagoon built a cement-bottomed pool that spreads out in a faux-organic layout and a clutch of modernist spa buildings. In 2017, the site accommodated 1.2 million visitors who buy timed entrance tickets and pay extra for bathrobes and drinks at the lagoon’s float-up bar. “Can you imagine how many people have sex in it?” the Icelandic politician Birgitta Jonsdottir later asks me. The 240°C water that gets pumped from deep underground is so mineral-heavy, however, that no bacteria can survive, even after it gets cooled down to bathing temperature for visitors to soak in.

I get a wristband for locker access and cash-free payments then make my way through the bustling locker rooms. Guards in all-black uniforms yell at guests for not showering nude and scrubbing down according to Icelandic hygiene, helpfully illustrated by explicit diagrams. The hot water is a fast cure for my jet lag but the lagoon feels like a crowded hot tub. The first thing I notice after I get a plastic goblet of prosecco and smear my face with some local silica — filtered out of seawater by precipitation and served up in a bucket — is just how international the crowd is. An Indian family snaps selfies, holding each other’s drinks. A German man asks me to take a photo of his friend and send it to him, maybe because I had followed the advice of travel blogs and squeezed my phone into a nerdy waterproof bag strung around my neck. I hear as much Chinese as English.

:no_upscale()/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/19276030/Vox_tourism_iceland_025.jpg)

An American man floating by declaims to his friends, “Can you imagine if we built a concept like this in Las Vegas?” And that’s exactly what the Blue Lagoon is: a concept, a playground-Iceland that can be consumed at will, something packaged and branded as representative of the place despite its artificiality. (One Trip Advisor review deems it “ expensive and fake .”)

The rest of the resort follows the same logic. When I begin feeling like a wobbly sous-vide egg I wade out of the water, shower again, and go inside for my reservation at Lava, an upscale restaurant where one wall is polished lava-rock and two others are floor-to-ceiling glass. Guests in the same white robes as mine dot the tables like hospital patients in a waiting room. I order the $50 two-course set menu that features local lamb. It tastes transcendentally gamey and like nowhere else on Earth, literally, because Icelandic sheep were first brought to the island 1,000 years ago and left alone to evolve in uniquely delicious ways.

The condition of overtourism pressures places to become commodities in the global marketplace the same way we warp our lifestyles to attract Instagram “Likes.” “You have to compete as a brand,” Pálsdóttir tells me. Countries and cities must constantly perform their identities in order to maintain the flow of tourists.

Icelandic tourism is a paradox. Visitors might outnumber locals, but the place must take care to preserve the brand of lonely natural grandeur that has become its product, offered up like a dish of roast lamb belly. The maintenance of this image is its own kind of artificiality. Fun fact: If an Icelandic horse ever leaves the island, it isn’t allowed to come back.

My Reykjavik Airbnb was listed on the website as a penthouse, but that’s not hard to achieve when few buildings are more than three stories tall. It’s polished and pleasantly anonymous without lacking personality entirely; above the TV there’s a giant photo print of the Brooklyn Bridge. From the balcony on one side I can see the white specter of Snæfellsjökull, a glacier-capped stratovolcano, across the chilled blue of Faxa Bay. On the other is downtown Reykjavik, like an overgrown ski town, with the skeletons of new hotels and high-rise glassy condos under construction on the outskirts.

Though Airbnb initially helped the growth of Icelandic tourism by housing visitors while development was only in planning, the government instituted a new regulation in January 2017 limiting most short-term rentals to 90 days a year; more than that and the owners need special certification. My place clearly falls into the latter category, since the owner rents out the building’s two penthouse apartments full-time and lives in a unit below them. The apartment is on a quieter stretch of the main shopping strip, Laugavegur, sprinkled with storefronts selling outdoor gear, souvenir puffin dolls, and Viking kitsch. It’s easy to tell tourists apart from the locals because they wear brightly colored Gore-Tex coats despite the relative warmth, and wander aimlessly, unsure of where they’re going. When I go out I try to wear a casual jacket and carry a tote bag instead of a backpack, wanting, illogically, to be disguised.

:no_upscale()/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/19276033/Vox_tourism_iceland_112.jpg)

These days, Reykjavik is full of the kinds of signifiers that mark an “authentic” travel experience, at least according to the influencer set: artisanal coffee shops like Reykjavik Roasters, locavore restaurants like Skál, and shops with names like “Nomad.store” selling minimalist coffee-table books and scented candles. None of these things are bad, necessarily, but they’re also not particularly local to Iceland in the first place. Unlike Paris, for example, where the centuries-old urban culture is what attracts visitors, Reykjavik developed in tandem with tourism.

“I grew up in the city center and I remember the streets used to be empty. It was a small fraction of the cafes and restaurants you have now,” says Karen María Jónsdóttir, at the time the director of Visit Reykjavik, the marketing office for the city. We’re sitting in The Coocoo’s Nest, a homey farm-to-table bar-slash-restaurant in the harbor neighborhood, where old fishermen’s supply sheds are being turned into boutiques and food halls in a familiar flavor of industrial gentrification. We drink two fashionably non-alcoholic lemonade cocktails at the wood bar. Icelanders used to only go out on the weekends and shop at outlet malls outside the city; now things are open all week long. “You need a certain mass of people to [sustain] a selection of good restaurants and services for everybody,” Jónsdóttir says. “We all want the services but then we complain about the people using them.”

Gunnar Jóhannesson, a professor at the University of Iceland who studies tourism, tells me about a recent survey: the closer to the center of Reykjavik, the more positive locals are in their perception of tourists. We need to “re-humanize tourists and tourism,” Johannesson says. “It’s important to stop thinking about tourism as the other and realize that we are also tourists. Tourism is part of our society.” (After all, whenever Icelanders leave their small island, they’re tourists too: According to data sent to me by Visit Iceland, 83 percent of Icelanders traveled abroad for vacation in 2018.) There’s a “standardization” that follows global travel, the professor says, a wave of generically luxurious cafes, hotels, and food halls. “Maybe it’s a bit comforting. It shows that people like the same things.”

Perhaps the problem isn’t the actual tourists but the way that some people — international entrepreneurs and developers in particular — profit from the tourism industry while others don’t. In other words, extractive capitalism is at fault, causing gentrification and displacement. “When tourism grows out of proportion, when it starts to be based on and motivated by international capital but not the community’s values, then we might have a problem,” Johannesson says. “I don’t think it has gotten to that point in Iceland, but it easily can get there.” Of course, it’s easier to say that on an island with plenty of extant empty space than at a Barcelona market so crowded with people Instagramming produce that residents can’t actually shop there.

Whether the balance has already tipped in favor of capital depends on who you ask. One evening I open Yelp and search the city for natural wine bars , which are the latest international hipster shibboleth and the 2010s update to Thomas Friedman’s Golden Arches Theory of peace-via-globalization: Instead of McDonald’s, no two countries with natural wine bars will ever go to war with each other. I head to Port 9, down the alleyway of a residential complex. It’s a faux-industrial space with raw cement walls, hanging pendant lamps, and plush green-velvet banquettes, like every other cool bar . A piece by minimalist composer Steve Reich is playing. Wine connoisseurship is itself a recent import in Iceland; the country had a form of alcohol prohibition from 1915 to 1989, and beer is far more popular.

Sitting at the bar are two young men swirling glasses with the bartender. They are both musicians and graduate students in the whimsical, long-term manner enabled by Nordic socialism. They both recently moved back from Berlin, nostalgic for the Icelandic summer and nature in general. Markus Sigur Bjornsson is wiry and wry, dressed in streetwear, while Thorsteinn Eyfjord is taller, neck-scarved and more formal in manner. We discuss the state of the country over a funky Italian red pulled from under the bar. Bjornsson says he might not have ever left his home if it weren’t for exposure to tourists showing him that an outside world existed (Iceland is 93 percent Icelandic; the second largest demographic is Polish at 3 percent). “The tourism bubble, in 20 years we can look back and think, okay, this did more positive than negative to our society,” he says. In fact, as Elvar Orri Hreinsson, a research analyst at the Bank of Iceland, tells me, Iceland is more financially secure now than it used to be, even with the slowdown: The economy is more diversified, the central bank holds a large currency reserve, and foreign investors are more interested than ever.

Eyfjord is more pessimistic. Like most millennials, he feels a looming generational burden. If the bubble bursts, “we will have to take the blame and build up society again,” he says. But he has a plan. Without tourists, there will be a lot of empty hotels and Airbnbs. “I hope there will come a wave of squatting and the young people and artists will take over.” The spaces could be turned into affordable housing, art studios, and startup offices. “Then at least I can live alone without having to have help from my parents.”

:no_upscale()/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/19276071/Vox_tourism_iceland_039.jpg)

The rise of isolationist nationalism might slow it and climate change, accelerated by every plane flight, will change its targets, but as a global growth industry tourism doesn’t seem likely to stop. We can’t return to a time when overtourism didn’t exist, and the desire to do so is as problematic as the concept of overtourism itself: there’s prejudice at work when wealthy, white Westerners have been tourists, if not colonizers, for centuries, but now that the rest of the world is joining in, it’s cast as excessive. Rather, the task left to us is to imagine a post-overtourism world in which we can all participate in and benefit from the human flow.

I meet Birgitta Jónsdóttir, the 52-year-old former Icelandic Parliamentarian and onetime friend of Julian Assange, in a Fleetwood Mac-soundtracked hostel cafe that she suggests near her apartment in a quieter area east of downtown. Across the street, children bounce on a trampoline. As the former face of Iceland’s Pirate Party, a loose, global coalition of digital freedom activists that was the most popular political party in the country between 2015 and 2016, Jonsdottir is something of a celebrity. Icelandic style is usually sober; she has purple-tinged eyelashes, iridescent nails, dyed-blonde hair, and a set of chunky, biomorphic rings, a contrast to her anonymous black winter jacket.

While in Parliament, she tried to pass a bill that would tax new hotels and direct the funds toward Reykjavik itself but was stymied “because people in the countryside wanted their share of it,” she says. The funding would fight what she calls the “Disneyfication” of Reykjavik as well as help safeguard the area’s natural sites. “A lot of places I hold sacred in nature, places I would go to get some energy, there are so many people, so noisy, so disrespectful to the space they’re in, that I don’t go there anymore. I just get very upset,” she says. “You do not become sympathetic to other people’s cultures just tracking through it like a horde of oxen.”

She thinks we might need a different kind of tourism altogether. Rather than her old favorite spots that are now overrun, these days Jonsdottir prefers exploring her own backyard garden, a choice that’s both quieter and less damaging. She plants potatoes, like her family did in the village where she grew up. “I have a different experience every day because of the weather and the way the plants grow,” she says. “Look at the crisis we’re in with our planet. It’s time that people go on trips in their own area and say goodbye to the diversity that is there.”

There’s a blank-slate quality to Iceland, extending to the freshness of the air itself. The place has spun stories around itself since the Vikings wrote down their Sagas, tales of family lineages and heroic deeds, in the 12th century — some of which went on to inspire a novelist named George R.R. Martin. The landscape has had many things projected upon it. “There are different layers to the fantasy of Iceland,” the Icelandic novelist Andri Magnason tells me over dinner at Snaps, an old-school French bistro beloved by locals down the street from Hallgrímskirkja, the wave-like, expressionist church that is one of Reykjavik’s best-known symbols. “The Sagas are one layer, Game of Thrones is another layer, maybe the economy is another.”

:no_upscale()/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/19276085/Vox_tourism_iceland_003.jpg)

The fantasy can be the attraction. Early one morning I climb onto a coach bus familiar from childhood field trips for an eight-hour tour of Game of Thrones shooting locations. In the front of the bus sits our bearded guide, Theo Hansson, who is wearing a Night’s Watch outfit complete with faux-fur cape, drinking horn on his belt loop (I watch him fill it with coffee), and two actual swords, his long hair tied back with a bandana. Hansson explains that he worked as an extra on the show in various seasons playing a Watchman, an undead wight, and a wildling, braving thin costumes, recalcitrant horses, and very bad weather. Hansson speaks in a deep growl that’s half Hound rumble and half Littlefinger hiss; I assume it’s a put-on until he later speaks on the phone the same way, his voice shot from a day of narration. A Reykjavik native, in Hansson’s off-time he is an academic studying Viking history at the University of Iceland.

“I really, really hate tourists,” Hansson growls with feeling. “But you guys aren’t tourists. You’re Game of Thrones enthusiasts.” The tour happens the day after the finale of the television show, which I had stayed up very late Iceland time to watch, using a proxy to access American HBO. I’m the only one in the group to have done so, and so no one else is massively disappointed yet. I’m jealous.

On the bus are two-dozen other tourists, mostly American, including John and Marsha, an older couple from Buffalo, New York. They booked a free stopover through an OTA when it popped up as an option on their flights back home from Copenhagen, following a long cruise. “We never even thought of Iceland. I couldn’t even spell Reykjavik,” Marsha tells me. But it turned out their neighbor had just visited and loved it, then a woman they met on the Copenhagen flight suggested this specific tour. Marsha says she wishes they had planned to stay for a day longer.

Hansson swears a lot, tells repeated ex-girlfriend jokes, and puns incessantly. He’s had the gig since 2016. “This used to be a normal tour, then it became an R-rated tour,” he says. His humor has offended some groups, especially Germans, but his boss has been on the tour and loved it. In between anecdotes, we make our stops, like Thingvellir, where Vikings established Iceland’s first parliamentary government, the Althing, in the 10th century, in a ravine-ridden field where the earth is actively splitting apart. It’s also where Game of Thrones shot the Bloody Gate, an elaborate tiered guardhouse outside of the Eyrie castle, in season four. Hansson holds up laminated screenshots from the show that he printed out himself so that we can see the precise camera angle and observe that reality conforms to the image, except, of course, for the missing CGI gate. We ooh and aah.

Westeros is not a real place. Even the northern parts of the show were shot between Iceland, Scotland, and Ireland then spliced together as if they were contiguous. But we are tourists of the fiction regardless. Hansson brings us to Þjóðveldisbærinn Stöng, a replica of a Viking-era farm on a hilltop, where the show shot a Wildling raid. Hansson was in the scene; his job was to chase down a 6-year-old child. “I just kept stabbing her again and again and again. It was marvelous,” he says. Then he selects a volunteer from the audience and proceeds to demonstrate the stage-stabbing technique.

I drift away from the group and lean up against the grassy sod that covers the entire structure of the farmhouse to insulate it from the weather and cold. It starts to rain, but the grass shields me just enough so that I can look out into the gray mist over the surreal landscape, which stretches and pitches into hills and valleys like a skate park for giants. I feel briefly connected to some universal sentiment: the authentic dreariness of the Vikings and the Game of Thrones villagers alike.

My Golden Circle tour is more prosaic. I climb aboard another bus, this time filled with a group of quiet Norwegians and a single American family with two rambunctious kids; I’m the only solo traveler. Emil, the tour guide, has an affectless storytelling style, like a podcast of Wikipedia entries, much less appealing than Hansson’s profane patter. Whenever we stop, he seems more interested in talking to our otherwise silent driver, whose name he says is Gummy Bear, than explaining anything. On the itinerary is Thingvellir again, sans CGI; Geysir, the much-photographed clutch of geysers on a hillside; Gullfoss, an iconic waterfall; and the Secret Lagoon, a not-so-secret geothermal spring whose ironic slogan is “We Kept It Unique for You.”

:no_upscale()/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/19276094/Vox_tourism_iceland_005.jpg)

Geysir actually refers to the single Great Geyser, but that one only erupts around earthquakes. The star of the show is Strokkur (Icelandic for “churn”), which explodes every 10 minutes or so, causing a great gasp from the assembled visitors. Rings of tourists face backward and lean over the boiling-hot water in order to take possibly fatal selfies. Footprints mark a trodden path in the muddy hill that winds around each pool.

More than a natural wonder, it’s now something of a highway rest-stop, grandiose in its attempt to cater to tourists. On the other side of the road from the geysers is a sprawling visitor center, featuring a huge store selling clothing from the brand Geysir, one of Iceland’s most recognizable fashion labels, named after the place itself. The food court offers pizza as well as fish and chips readymade under heat lamps. Next door is a newly developed spa hotel, geyser-themed. Compared to the infrastructure, the waterworks themselves seem even smaller and less remarkable. I recall Markus Bjornsson, the student in the wine bar: “If you’ve seen one geyser, you’ve seen them all.”

Gullfoss — Golden Falls — is a mammoth crack in the earth through which runs 140 cubic meters of water per second. The gathered force is like a nuclear bomb but all the time. There were attempts to turn the falls into a hydroelectric power plant, but the story goes that the daughter of one of the farmers who own the land mounted a charismatic protest and saved it. Now there’s a beaten trail with staircases and handrails along the lip of the canyon where we could look down and take photos. Patches of grass that draw even closer to the edge are blocked off with signs. (“If you fall over, it’s impossible to find you, you’re just gone,” Skarphéðinn Berg Steinarsson of the ITB tells me.) We stand with our phones in front of our faces, the surging water too massive to consider as reality, as anything other than a picture that we can save to show friends later, shorn of its existential dread. I think of Don DeLillo’s description of “the most photographed barn in America” in his novel White Noise : “No one sees the barn.”

In the face of overtourism, I want to make an argument for the inauthentic. Not just the spots flooded with tourists but the simulations and the fictions, the ways that the world of tourism supersedes reality and becomes its own space. It is made up of the digital northern lights on an 8K movie screen, the manmade turquoise geothermal baths, and the computer renderings of high-budget television shows overlaid on the earth. I don’t regret any of these activities; in fact, the less authentic an experience was supposed to be in Iceland, the more fun I had and the more aware I was of the consequences of 21st-century travel.

This is not to discount the charm of hiking an empty mountain or the very real damage that tourists cause, disrupting lives and often intensifying local inequality. But maybe by reclaiming these experiences, or destigmatizing them, we can also begin regaining our agency over the rampant commodification of places and people. We can travel to see what exists instead of wishing for some mythical untouched state, the dream of a place prepared perfectly for visitors and yet empty of them. Instead of trying to “ live like a local ,” as Airbnb commands, we can just be tourists. When a destination is deemed dead might be the best time to go there, as the most accurate reflection of our impure world.

:no_upscale()/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/19276102/Vox_tourism_iceland_052.jpg)

Back at my Airbnb, I call Theo Hansson to see what he thought of the end of Game of Thrones . He was, like me, dissatisfied. “I’m very glad I was not a part of the last season. It would have soured everything,” he says. He doesn’t expect his gig to last forever. In 2016, “I was doing groups of 40 or 50 people to 100 people. It’s gotten a lot less,” he tells me in a low, hoarse rumble. “I’m expecting maybe two years more of this. The engine is going to fade.” Game of Thrones will drift away like the other narratives, maybe faster than slower.

Hansson’s other sideline, making use of his academic background, is being a Viking reenactor. He’s in a group of 200 people, not just born-and-bred Icelanders, who train in sword-fighting, archery, and crafts. They camp out for a week at a time, wearing period-correct clothing and sleeping in Viking tents based on archaeological discoveries. They fight, cook food over open fires, and get very drunk.

This is what refreshes him, participating in the illusion of another life, which is the same thing that we’re always seeking when we travel: to get outside of ourselves and imagine new possibilities, however unlikely or unreal they are. Iceland remains ideal for this purpose. “It’s what fantasies are made of,” Hansson says. “This untamed wild, this alien landscape, this vastness.”

Will you support Vox today?

We believe that everyone deserves to understand the world that they live in. That kind of knowledge helps create better citizens, neighbors, friends, parents, and stewards of this planet. Producing deeply researched, explanatory journalism takes resources. You can support this mission by making a financial gift to Vox today. Will you join us?

We accept credit card, Apple Pay, and Google Pay. You can also contribute via

How do I stop living paycheck to paycheck?

Boeing’s problems were as bad as you thought, you could soon get cash for a delayed flight, sign up for the newsletter today, explained, thanks for signing up.

Check your inbox for a welcome email.

Oops. Something went wrong. Please enter a valid email and try again.

- Share full article

What Worries Iceland? A World Without Ice. It Is Preparing.

As rising temperatures drastically reshape Iceland’s landscape, businesses and the government are spending millions for survival and profit.

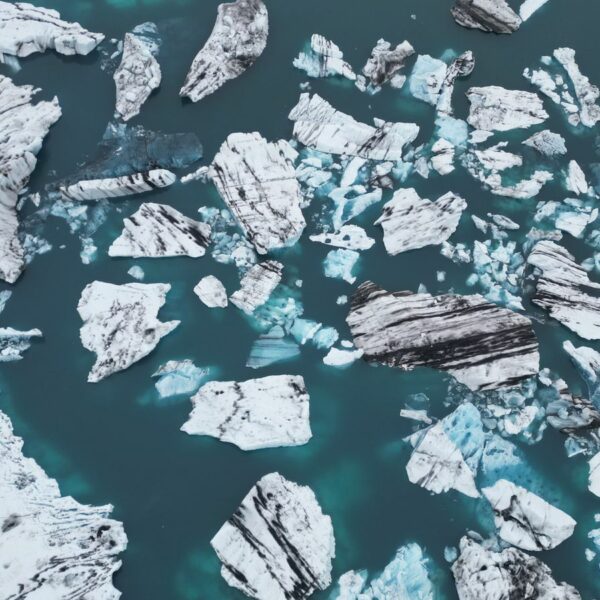

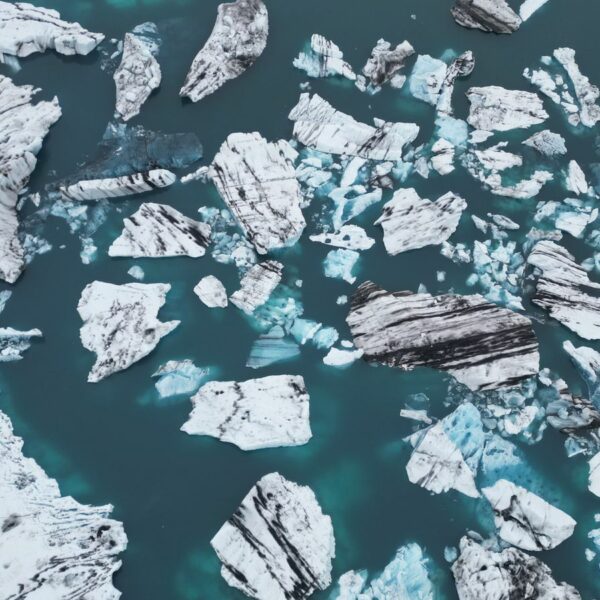

A melting glacier in Iceland. Glaciers occupy over a tenth of this famously frigid island near the Arctic Circle. Credit... Suzie Howell for The New York Times

Supported by

By Liz Alderman

- Aug. 9, 2019

HÖFN, Iceland — From the offices of the fishing operation founded by his family two generations ago, Adalsteinn Ingólfsson has watched the massive Vatnajökull glacier shrink year after year. Rising temperatures have already winnowed the types of fish he can catch. But the wilting ice mass, Iceland’s largest, is a strange new challenge to business.

“The glacier is melting so much that the land is rising from the sea,” said Mr. Ingólfsson, the chief executive of Skinney-Thinganes , one of Iceland’s biggest fishing companies. “It’s harder to get our biggest trawlers in and out of the harbor. And if something goes wrong with the weather, the port is closed off completely.”

A warmer climate isn’t affecting just Höfn, where the waning weight of Vatnajökull on the earth’s crust is draining fjords and shifting underground sediment, twisting the town’s sewer pipes. As temperatures rise across the Arctic nearly faster than any place on the planet, all of Iceland is grappling with the prospect of a future with no ice.

[In Scandinavia, climate change is leading entrepreneurs to invest in wineries.]

Energy producers are upgrading hydroelectric power plants and experimenting with burying carbon dioxide in rock , to keep it out of the atmosphere. Proposals are being floated for a new port in Finnafjord , now a barren landscape in the east, to capitalize on potential cargo traffic as shipping companies in China, Russia and Arctic nations vie to open routes through the melting ice. The fishing industry is slashing fossil fuel use with energy-efficient ships.

Glaciers occupy over a tenth of this famously frigid island near the Arctic Circle. Every single one is melting . So are the massive, centuries-old ice sheets of Greenland and the polar regions. Where other countries face rising seas, Iceland is confronting a rise in land in its southernmost regions, and considers the changing landscape and climate a matter of national urgency.

When Europe suffered record-breaking heat in July, Iceland’s capital, Reykjavik, clocked its highest temperatures ever. Iceland’s economy is on the cusp of a recession , partly because an important export, the capelin fish, vanished this year in search of colder waters. This week, the United Nations warned that the world’s land and water resources are being exploited at an unprecedented rate.

“Climate change is no longer something to be joked about in Iceland or anywhere,” Gudni Jóhannesson, Iceland’s president, said in an interview, adding that most Icelanders believe human activity plays a role. “We realize the harmful effects of global warming,” he said. “We are taking responsibility to seek practical solutions. But we can do better.”

The country elected an environmentalist, Katrín Jakobsdóttir, as prime minister in 2017 on a platform of tackling climate change. Her government is budgeting $55 million over five years for reforestation, land conservation and carbon-free transport projects to slash greenhouse gas emissions . More will be spent by 2040, when Iceland expects businesses, organizations and individuals to be removing as much carbon dioxide from the atmosphere as they put in.

Environmental activists say that still isn’t enough to make Iceland, a wealthy nation of just 350,000 people, a model. Despite generating clean geothermal energy and hydropower, major industries including aluminum and ferrosilicon production also produce a third of Iceland’s carbon dioxide. Tourism, now the engine of growth after a banking collapse in 2008, has flourished with warmer weather but added to Iceland’s climate woes as planes packing millions of visitors push per capita carbon dioxide emissions above that of every country i n Europe.

Bigger nations like Norway and Finland have cut emissions more, and over 190 other countries except the United States have pledged to combat climate change under the Paris agreement. But with the impact in Iceland more visible than in other nations, it is doing what it can — while trying to turn the warming climate into an economic advantage.

“Let’s look at practical solutions instead of being filled with despair,” Mr. Jóhannesson said.

Ólafur Eggertsson, a farmer, has been anticipating how to tame the wilds of his new environment. On a sunny day, he pointed to a sparkling glacier sprawled thinly atop the nearby Eyjafjallajökull volcano on Iceland’s southern rim. Eyjafjallajökull erupted spectacularly in 2010, snarling European air traffic and raining ash over the Thorvaldseyri farm run by his family since 1906. But even before that, the glacier had been visibly retreating, and far faster than when his father and grandfather worked the land.

That alarms him, he said, because glaciers keep volcanoes cool. Scientists predict more eruptions in the coming century as the glaciers melt. Mr. Eggertsson is working to make the farm carbon neutral to prevent more warming, by transforming it from a mainly dairy operation to an 160-acre estate with barley and rapeseed fields — crops that couldn’t grow in the cold climate 50 years ago.

He is converting the rapeseed to biofuel. And Mr. Eggertsson, who plans to ramp up his 364,000-euro investment in the crop business in coming years, is hoping that Iceland’s farmers will one day grow enough barley to avoid importing it on polluting ships and planes.

“Sometimes what I’m doing feels like a drop in the ocean,” Mr. Eggertsson said, pulling handfuls of barley from the soil. “But humans are contributing to warming. I have no choice but to act.”

Others are finding deals in the demand from companies and people eager to offset their carbon footprint. Near Mr. Eggertsson’s farm, Reynir Kristinsson this year planted 200,000 native birch trees on 700 acres of volcanic flatland that his nongovernmental organization, Kolvidur , leases from the state.

More than a million trees have been purchased by Icelandic companies and foreign ones like Ikea since 2010. Mr. Kristinsson is negotiating with Isavia, Iceland’s airport operator, in hopes of crafting a deal to plant trees for every tourist and Icelander who flies in and out of the island, and is bidding to lease 12,000 more acres, forecasting “exponential growth.”

Some companies are just trying “to green wash” their image, Mr. Kristinsson acknowledged. But as consumers demand transparency, businesses are more serious about protecting the environment and know they have to spend substantial money toward battling the changes. “If they don’t show they’re acting responsibly, they will lose clients,” he said.

Yet most of Iceland’s volcanic terrain is deforested , and it will take decades for newly planted trees to absorb carbon at a large scale. Trees are certainly not a fast fix for Iceland’s glaciers, which scientists say now can no longer recover the ice they are losing.

That includes Vatnajökull, which once stretched over more than a tenth of Iceland and now covers 8 percent of this 40,000-square mile island. Named a Unesco World Heritage site in June, it is shrinking by a length of nearly three football fields a year in some places.

In Höfn, Mr. Ingólfsson’s business has been thwarted by the change. While the land here has risen nearly 20 inches since the 1930s, in the last decade alone, it has floated four inches above sea level. It is forecast to rise as much as six feet in the coming century, according to the Icelandic Meteorological Office.

That new land is preventing Mr. Ingólfsson from acquiring bigger-capacity trawlers that his competitors use. HB Grandi, a Reykjavik-based rival that is one of Iceland’s largest fishing companies, has invested in enormous super-trawlers that use less fossil fuel and allow for a larger catch. This year, cold water capelin can’t be found. But mackerel are now swimming in the warmer currents around Iceland, and the value of the catch has risen noticeably.

Such investment — which also translates into smaller fleets — is running through Iceland’s fishing industry, and fits a national strategy to reduce carbon emissions that contribute to ocean acidification and harm fish. The transformation is important and strategic: Fish account for 39 percent of Iceland’s exports .

Mr. Ingólfsson’s trawlers can now move in and out only at high tide, and his business suffers for that. Last winter, two were stuck outside the harbor when a storm hit, he said, forcing the catch to be offloaded at another factory on the east coast, leaving scores of workers at his Höfn plant idle.

“Unless we find a solution,” he said, “things will just get worse.”

Glacial melting is also expected to oversaturate watersheds in the next century, and scientists predict that they then will dry up, forcing energy producers to adapt. Landsvirkjun , the state-run energy company, which generates three-quarters of Iceland’s power, is building room for additional water turbines at its dams. It is also building new capacity for wind turbines to operate when the glaciers die.

“From a design perspective, we’re taking into account what will happen in the next 50 to 100 years,” said Óli Grétar Blondal Sveinsson, the executive vice president for research and development. “There will be no glaciers,” he said flatly.

That prospect has jolted Icelanders — and some visitors — to a realization that they are witnessing a treasure vanish. Steinthór Arnarson, 36, quit his job as a lawyer three years ago to open a tour business at the Fjallsárlón lagoon, employing 20. He takes visitors on inflatable boats around iceberg-studded waters that barely existed two decades ago.

A native of the area, he recalled the lake’s being a fraction of its current size when he was a teenager. When he returned in 2012, the Vatnajökull outlet here had melted so much that the lagoon had grown a mile wide, and thundering rivers nearby had shifted course.

Many of the 200 tourists who visit daily want to see Vatnajökull before it disappears, Mr. Arnarson said.

“People are stunned by the glacier’s beauty and feel like me,” he said, gazing at the 130-foot-high wall of blue ice soaring from the water.

“It’s nice to see a piece of it break off,” he said. “But it’s really sad.”

Egill Bjarnason contributed reporting.

Explore Our Business Coverage

Dive deeper into the people, issues and trends shaping the world of business..

A Lead in Green Energy: A subsidiary of ThyssenKrupp, Germany’s venerable steel producer, is landing major deals for a device that makes hydrogen, a clean-burning gas, from water.

A Wealth Shift: Assets held by baby boomers are changing hands, but that doesn’t mean their millennial heirs will be set for life.

Daniel Ek’s Next Act: The Spotify chief has co-founded a new start-up, Neko Health, that aims to make head-to-toe health scans part of the annual health checkup routine.

Handling Finances: People who suddenly lose a spouse while young can feel unprepared for what their future looks like. Here’s how to be prepared .

What Would Jesus Do?: The “Yes in God’s Backyard” movement to build affordable housing on faith organizations’ properties is gaining steam in California and elsewhere.

What Is a ‘Decent Wage’?: Michelin, the French tire maker, vowed to ensure that none of its workers in France would struggle to make ends meet.

Advertisement

Iceland and the Trials of 21st Century Tourism

Once, iceland’s top industry was fishing. then, heavy industry took over. now, tourism drives economic growth in iceland. what are the challenges that increased tourism creates for a unique nation like iceland.

Foreword: The Coming Perils of Overtourism

As Skift enters its fifth year , we are going wider with our coverage of the global travel industry and its effect on the world. The original promise of Skift — the first line in the first-ever business deck we created — was “Travel intersects with every sector in the world from local, national, state, and foreign policy to design, branding, marketing and more.”

As part of that promise, we are starting a series of deep dives into destinations, as a mirror to the larger changes that are happening around the world due to the democratization of global travel over the last two decades.

We are coining a new term, “ Overtourism ”, as a new construct to look at potential hazards to popular destinations worldwide, as the dynamic forces that power tourism often inflict unavoidable negative consequences if not managed well. In some countries, this can lead to a decline in tourism as a sustainable framework is never put into place for coping with the economic, environmental, and sociocultural effects of tourism. The impact on local residents cannot be understated either.

As the world moves towards two billion travelers worldwide in the next few years, are countries and their infrastructure ready for the deluge? Are the people and their cultures resilient enough to withstand the flood of overtourism?

When Skift took the team to Iceland in early summer of 2014, we wrote a story after about how “Iceland is the perfect crucible of a lot of global travel trends we cover on a daily basis on Skift, converging in the tiny country in so many ways over the last few years.”

And converging they are in a big way.

Iceland’s recovery from the depths of the 2008 financial crisis has been remarkable, and is built on the back of an explosive growth in tourism. From 2009 onwards, its tourist growth has been a hockey curve, and now a population of 350,000 residents will welcome about 1.6 million tourists this year.

In 2016, we wanted to look at Iceland as a mirror to the larger changes that happen in a destination when the democratization of global travel meets the willingness of destinations to make tourism as the growth engine of their region.

The Skift investigation explores the problems: beginning with gateway problems at its primary airport, to hotel infrastructure, to Airbnb running rampant, to too many tourists with too little understanding of the ecological fragility of the country, to climate change and tourism’s effect on it, to too few trained tourism professionals in the country, to tour operators feeling the burden, to pressure on understaffed local police, to hollowing out of Reykjavik's downtown, to early signs of locals resenting tourists, and more.

If a first-world country like Iceland is having trouble with figuring out the solutions, what hope do countries like Cuba or Burma have?

That’s the lens we are putting on this long deep dive below, with lessons for everyone in the travel and tourism industry, city and regional planners, and the larger support ecosystem.

— Rafat Ali, Founder & CEO, Skift

Introduction

In Norse culture, there is a saying: Sjaldan er ein báran stök. There is seldom a single wave.

The island nation of Iceland, which is roughly the size of Portugal and located about 1,100 miles northwest of London, is a flashpoint for the encroaching forces of tourism and globalization.

When the global financial meltdown hit Iceland in 2008, it unleashed a series of devastating consequences: an unprecedented banking crisis, a housing market collapse, and increased unemployment. Iceland’s currency plummeted in value and thousands in export-heavy jobs were put out of work.

Iceland’s natural beauty, and the character of its people, had always been attractive to travelers. Now, both bargain-seeking adventurers and wealthy vacationers looking to cross Iceland off their bucket list can visit.

Tourism in Iceland increased from 18.8 percent of the country’s foreign exchange earnings in 2010 to 31 percent in 2015. Those are some staggering hot-startup-like growth rates. Especially for a country.

Over the same period, tourism surpassed both fishing and aluminum production to become Iceland’s top industry.

In many respects, tourism has saved Iceland from economic hardship and provided the country a solid platform to regrow its economy. The influx of tourists, however, represents something ominous to some native Icelanders.

Iceland’s infrastructure, particularly the network of roads that cut across the island’s mountainous terrain, is in dire need of renovation as an increasing number of tour buses hit the roads each day.

The country’s most popular natural landmarks are under threat from the environmental impact of more tourists visiting during the winter months.

The economic focus on catering to tourists has taken a cultural toll on the country, as well.

While global travel trends have converged in Iceland, travel has also brought the country its share of unprecedented troubles.

In June, Skift went to Iceland for a week-long reporting trip and spoke to more than a dozen leaders and players in tourism, from the man who runs Iceland’s most popular tourist destination to Airbnb superhosts building businesses due to the lack of available hotel rooms in Reykjavik.

Here is our deep dive.

Before You Go