The Most Essential Arabic Travel Phrases

Isn’t it exciting to imagine?

The crashing surf of a Moroccan beach or the tall and rugged mountains of Jordan . The streetside bazaars in Cairo or the resorts in Dubai .

And you’re there. Speaking in Arabic.

Or rather, that’s the plan, right?

You’re still working on it. And that’s okay. Arabic is a long, long journey for anybody.

Speaking of journeys, there are a couple of Arabic travel phrases that tourists need to learn in the local language, no matter where they go. In this article, I’ll outline some of the most useful travel phrases in Arabic for any traveler, tourist, or expat in an Arabic-speaking country. Let’s get started.

Table of Contents

- Using Modern Standard Arabic vs. Using Dialects

- The Most Essential Arabic Vocabulary and Phrases for Your Travel Needs

- Conclusion: ArabicPod101 is Your Guide to Arabic Mastery

1. Using Modern Standard Arabic vs. Using Dialects

Before you learn Arabic travel phrases, we need to go over the topic of MSA vs. dialects.

When it comes to Arabic words and phrases for travellers, this is a perpetual debate among Arabic learners.

Is it better to start with MSA or with a dialect? What if you’re planning to visit more than one country? What if you’re hanging out in a cafe in Egypt, and suddenly your friend from Iraq and his roommate from Morocco come in? What do you speak?

The position of this article is: Start with MSA . In terms of Arabic travel phrases for beginners, this is the best place to begin.

Most people in the Arab world won’t be able to speak MSA to you. They’ll do their best, but they may end up switching to another international language or just trying to make their local language sound as close to MSA as possible.

But you’ll be understood wherever you go, and when traveling, that’s what matters most. With a basic or intermediate ability in MSA, you can easily express your travel needs—not to mention read what’s written around you everywhere!

Once you’re able to express yourself in MSA, read up on the local language of wherever you’re planning to go, and listen to learning materials or native content as much as you can to get prepared for the answers you hear.

2. The Most Essential Arabic Vocabulary and Phrases for Your Travel Needs

Now, without further ado, here are Arabic travel phrases for your trip that you need to know!

1- Basic Expressions

What types of things do tourists usually say?

Pretty much the same things over and over, it turns out. Being able to speak a language “at a tourist level,” to me, means that you can handle the situations that are likely to come up, without necessarily being able to hold a real conversation.

That means, for instance, that you can order, pay for, and maybe even compliment a meal pretty smoothly in Arabic, but if the cook asks if you have that kind of food in your own country , you might find yourself grasping for words.

But hey, you’ve got to start somewhere, right?

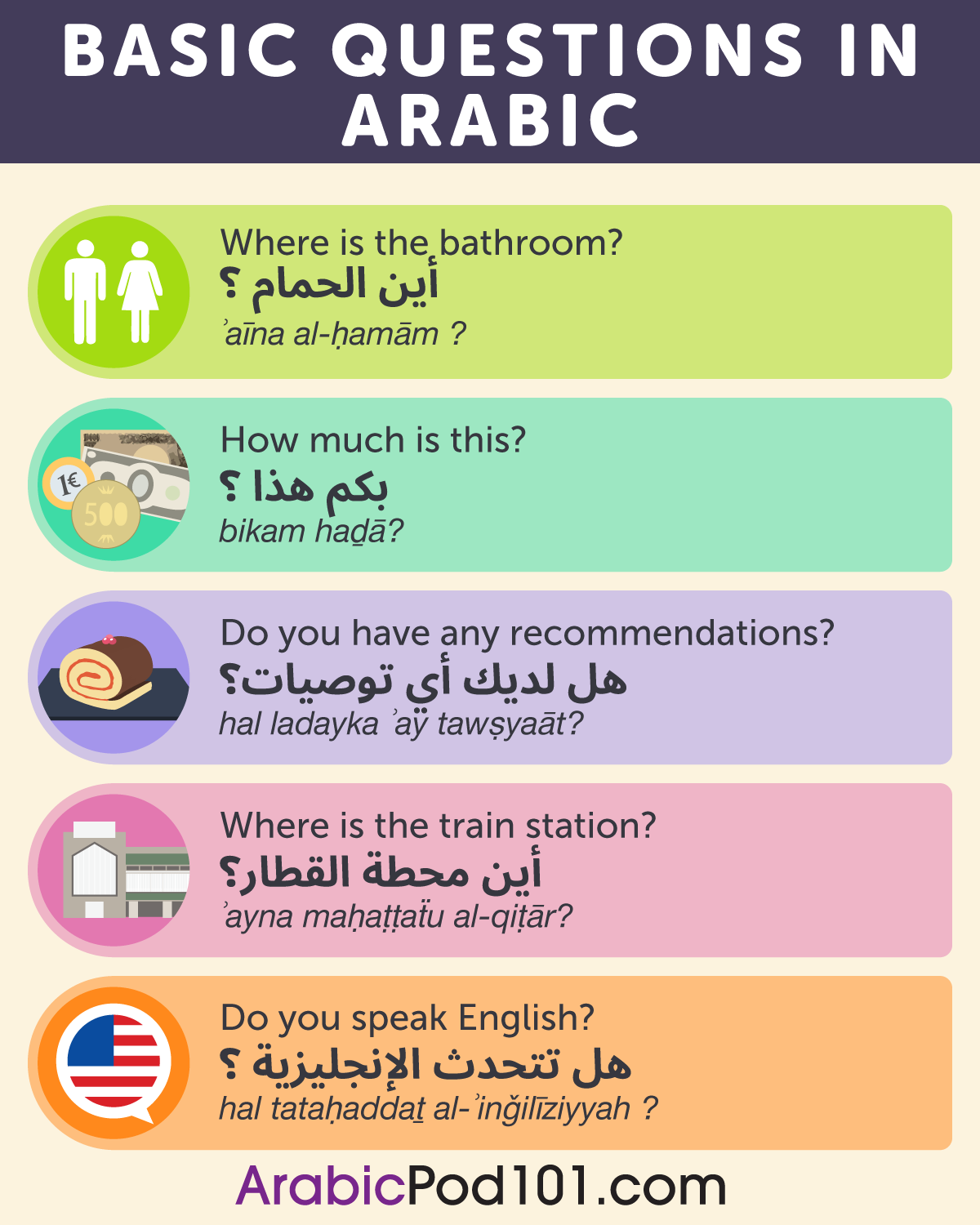

If you only look at one guide to tourist Arabic, it should be the next three paragraphs. Here, I go over the most important Arabic travel phrases, the one you shouldn’t be traveling without.

2- Greetings and Goodbyes

We’ll start with the first words out of anybody’s mouth: Hello.

- “Hello!” Ahlan! أَهلاً

In Arabic, there are appropriate hellos for the morning, evening, and night.

- “Good morning!” ṣabāḥu al-ḫayr صَباحُ الخَيْر

- “Good evening!” masāʾu al-ḫayr مَساءُ الخَيْر

- “Good night!” laylah saʿīdah لَيْلَة سَعيدَة

Now let’s have a look at how to properly address people that you need to talk to . How should you get their attention?

- “Excuse me. Could you tell me…” raǧāʾ, hal yumkinuka ʾiḫbārī… رَجاء, هَل يُمكِنُكَ إخباري…

And when you’ve finished what you need to do, it’s time to take your leave.

- “ Goodbye! ” ʾilā al-liqāʾ إلى اللِقاء

Although you can point and grunt your way through a language barrier, it’s simply good manners to be able to use a couple of nice words when the time comes .

- “This one, please.” haḏihi min faḍlik. .هَذِهِ مِن فَضلِك

Suppose you’re on the bus and an elderly man gets on. The polite thing to do is offer your seat with the phrase:

- “Go ahead.” tafaḍḍal. .تَفَضَّل

I personally always like to learn “thank you” in as many languages as I can, just in case. If there’s one phrase you remember after reading this article, make it this one.

- “Thank you!” šukran! !شُكراً

- “Thank you very much!” šukran ǧazīlan! !شُكراً جَزيلاً

Of course, guests aren’t the only ones doing the thanking. An exchange of “thank you” is likely to occur several times any time that money is exchanged for goods or services.

This means you’ll have to be ready with the “It’s nothing” and “Sure thing!” equivalent in Arabic.

- “No problem!” lā muškilah لا مُشكِلَة

4- Compliments

It’s amazing how far you can get in a foreign language by pointing, smiling, and saying “Good!” People simply love to hear that! And it’s one of the simplest Arabic-language travel phrases.

The word for “good” in Arabic is جَيِّد ( ǧayyid ). But you can do a little bit better .

- “I really like this!” yuʿǧibunī haḏā kaṯīran! يُعجِبُني هَذا كَثيراً!

For referring to food you just had:

- “It was excellent!” kān rāʾiʿan! !كان رائِعاً

For looking at a view from a room or complimenting something aesthetic:

- “This is so beautiful!” haḏā ǧamīlun ǧiddan! !هَذا جَميلٌ جِدّاً

5- Transportation

One pretty scary challenge in a foreign language is making a phone call. And if your language skills make the difference between arriving at the airport on time or arriving at the bus station two hours late, the pressure starts to get pretty high.

When you order a taxi in a foreign language, it’s a good idea to speak loudly and slowly, and probably repeat yourself a couple of times to make sure they understand.

The thing is, though, taxi companies are used to hearing the same sort of formula said over and over with a variety of different accents, so as long as you’ve got all the right words in there, you’re probably good to go.

- “I want to order a taxi to the airport for tomorrow morning.” ʾurīdu sayyāraẗa ʾuǧrah ʾilā al-maṭār ġadan ṣabāḥan. .أُريدُ سَيّارَةَ أُجرَة إلى المَطار غَداً صَباحاً

It never hurts to double-check:

- “Did you understand all that?” hal fahimt? هَل فَهِمت؟

Shuttle buses and minibuses are very popular in many Middle Eastern countries. Here are some vital phrases for dealing with those:

- “Does this bus go to…?” hal taḏhabu haḏihi al-ḥāfilah ʾilā…? هَل تَذهَبُ هَذِهِ الحافِلَة إلى…؟

- “Where can I buy a ticket?” ʾayn yumkinunī širāʾ taḏkarah? أَيْن يُمكِنُني شِراء تَذكَرَة؟

- “I want two tickets to … please.” ʾurīdu taḏkarataīn ʾilā… min faḍlik. أُريدُ تَذكَرَتَين إلى… مِن فَضلِك.

6- Shopping

When most people imagine shopping in Arabic , the first thing that comes to mind is that stereotypical image of a crowded street market.

You know the one: goats, toothless old men selling rugs, maybe a snake charmer in the corner. Something out of Indiana Jones .

Those definitely still exist (or at least street markets do), but don’t forget that big cities in the Arab world are pretty much like big cities anywhere else.

You’ll find just as many big air-conditioned malls with local and international brands. Need some Nikes or Levi’s? No problem.

And guess what? You’ll need Arabic there, too! Just because a brand is international doesn’t mean all the shop staff will be amazingly multilingual. That’s particularly the case if you go out of the touristed city centers and head to the other malls further out of the way.

- “Do you have a bigger size? / Do you have a smaller size?” hal ladaykum ḥaǧmun ʾakbar? / hal ladaykum ḥaǧm ʾaṣġar? هَل لَدَيْكُم حَجمٌ أَكبَر؟ / هَل لَدَيْكُم حَجم أَصغَر؟

- “I’m looking for jeans size 32/34.” ʾabḥaṯ ʿan sarāūīl ǧīnz min maqās ʾiṯnān wa ṯalāṯūn ʿalā ʾarbaʿah wa ṯalāṯūn. أَبحَث عَن سَراويل جينز مِن مَقاس إثنان و ثَلاثون عَلى أَربَعَة و ثَلاثون.

- “Can you make it any cheaper?” hal min taḫfīḍ? هَل مِن تَخفيض؟

- “Okay, I’ll take it!” ǧayyid, saʾāḫuḏuh جَيِّد, سَآخُذُه

Part of bargaining effectively is knowing when to quit, or perhaps when to fake quitting so that you can get a better deal. Whether or not you’re serious about walking away, it’s polite to say something like this as you go:

- “Maybe next time.” rubbamā fī al-marrah al-qādimah. رُبَّما في المَرَّة القادِمَة.

7- Restaurants

- “How do you say this?” kayfa yunṭaqu haḏā? كَيْفَ يُنطَقُ هَذا؟

It’s very likely that you’ll find things on the menu that you’re not able to pronounce. Depending on your study motivation, you might still have trouble with the Arabic alphabet when you arrive.

So you can ask somebody nearby to read out the name of the food. Maybe you’ve heard of something similar at another restaurant, or maybe it even has a loanword in its name that you’re familiar with.

- “What exactly is…?” mā … bilḍabṭ? ما … بِالضَبط؟

You may not understand the answer in its entirety—food words are notoriously specific and vary based on location. But the important thing is to keep your ears tuned for loanwords you may recognize, as well as the body language of the person you’re talking to. If they look like they’re holding back a smile or silently guessing that you won’t like it, better order something else.

Travelers with allergies can have a rough time of it in foreign countries. Many expats don’t speak the language of the country of residency except the words for things they can’t eat. It’s imperative to know those words well.

- “I’m allergic to …” laday ḥasāsiyyah min… لَدَيْ حَساسِيَّة مِن…

Here, you simply say the phrase, tacking on the name of the food you can’t eat. For a list of common food names, check out this vocabulary list on ArabicPod101.com. (It includes common allergens like peanuts and soybeans!)

Once you’ve enjoyed your meal and are ready to leave, you’d best know this phrase:

- “Can I have the bill, please?” hal yumkinunī ʾaḫḏ al-fātūrah laū samaḥt? هَل يُمكِنُني أَخذ الفاتورَة لَو سَمَحت؟

8- Directions

Directions are relatively complicated, and they’re not made any easier the way they get taught in a lot of coursebooks.

Have you ever noticed how in textbooks, people are always giving each other complicated directions in order to fit in as many vocabulary words as possible?

- “Where is …?” ʾayna…? أَيْنَ…؟

- “I’m looking for the…” ʾabḥaṯu ʿan… أَبحَث عَن…

- “It’s over there.” ʾinnahā hunāk. إنَّها هُناك.

- “Go straight down this road.” iāḏahab mubāšaraẗan ʿalā haḏā al-ṭarīq. .ِاذَهَب مُباشَرَةً عَلى هَذا الطَريق

- “You need to take the number 10 bus.” ʿalayka ʾan taʾḫuḏ al-ḥāfilah raqm 10. عَلَيْكَ أَن تَأخُذ الحافِلَة رَقم 10.

- “Is it far?” hal hiya baʿīdah? هَل هِيَ بَعيدَة؟

- “Can I walk there?” hal yumkinunī al-mašī hunāk? هَل يُمكِنُني المَشي هُناك؟

Really, these basic Arabic travel phrases are enough to get you from A to B in most cases. But it’s always good to have more complex direction phrases in your Arabic arsenal, just in case.

9- Emergencies

- “Do you have a bathroom?” hal ladaykum ḥammām? هَل لَدَيْكُم حَمّام؟

- “I lost my passport.” faqadtu ǧawaza safarī. فَقَدتُ جَوَازَ سَفَري.

- “I need to go to a hospital.” ʾanā biḥāǧah lilḏahāb ʾilā mustašfā. أَنا بِحاجَة لِلذَهاب إلى مُستَشفى.

- “May I please borrow your phone? It’s an emergency.” hal yumkinunī istiʿāraẗu hātifik? ladayya ḥal-ah ṭāriʾah هَل يُمكِنُني اِستِعارَةُ هاتِفِك؟ لَدَيَّ حالَة طارِئَة

- “My phone was stolen.” laqad tammat sariqaẗu hātifī. لَقَد تَمَّت سَرِقَةُ هاتِفي.

If you’ve lost something in a public space, you may be in luck if an honest stranger turned it in to the information desk. In that case, you can ask:

- “Did anyone find a laptop here?” hal waǧad ʾaḥaduhum ḥāsūban hunā? هَل وَجَد أَحَدُهُم حاسوباً هُنا؟

10- Language Troubles and Triumphs

Speaking Arabic when you’re out and about isn’t going to be all smooth sailing, no matter how easy it may seem when you’re flipping through a phrasebook.

There’s a helpful set of phrases that can really go a long way toward smoothing things over when your vocabulary or grammar fails you.

- “How do you say…?” kayfa taqūl…? كَيْفَ تَقول…؟

- “Does anyone here speak English? French?” hal yatakallamu ʾaḥaduhum al-ʾinǧlīziyyah ʾaw al-firinsiyyah hunā? هَل يَتَكَلَّمُ أَحَدُهُم الإنجليزِيَّة أَوْ الفِرِنسِيَّة هُنا؟

- “I don’t know that word.” lā ʾaʿrifu haḏihi al-kalimah. لا أَعرِفُ هَذِهِ الكَلِمَة.

- “Thank you! I’ve been learning for one year.” šukran. ʾanā ʾataʿallam min sanah. شُكراً. أَنا أَتَعَلَّم مِن سَنَة.

- “Sorry, my Arabic isn’t very good.” ʾāsif, luġatī al-ʿarabiyyah laysat ǧayyidah آسِف، لُغَتي العَرَبِيَّة لَيْسَت جَيِّدَة

- “Sorry, I can’t read Arabic very well.” ʾāsif , lā ʾastaṭīʿ qirāʾaẗa al-ʿarabiyyaẗa ǧayyidan آسِف ، لا أَستَطيع قِراءَةَ العَرَبِيَّةَ جَيِّداً

- “You just said ___. What does that mean?” laqad qult al-ʾān… māḏā yaʿnī ḏalik? لَقَد قُلت الآن… ماذا يَعني ذَلِك؟

3. Conclusion: ArabicPod101 is Your Guide to Arabic Mastery

Now that you’re packed with the most useful Arabic travel phrases, you’re all set for your next adventure. Want to learn even more Arabic? Check out ArabicPod101.com and get access to more than a thousand Arabic learning audio and video lessons that will take your Arabic to the next level.

Until next time, let us know how comfortable you feel with Arabic travel phrases. Is there anything you’re still struggling with? Drop us a comment and tell us about it!

Author: Yassir Sahnoun is a HubSpot certified content strategist, copywriter and polyglot who works with language learning companies. He helps companies attract sales using content strategy, copywriting, blogging, email marketing & more.

Or sign up using Facebook

Got an account? Sign in here

How To Say ‘Thank you’ in Arabic

Saying Hello in Arabic: What You Need to Know

How to Say I Love You in Arabic – Romantic Word List

Arabic Podcasts: The 5 Go-To Podcasts for Language Learners

Learn the Most Important Intermediate Arabic Words

The Names of Animals in Arabic (with Romanizations)

How to celebrate april fools’ day in arabic.

- Arabic Holidays

- Arabic Language

- Arabic Translation

- Scheduled Maintenance

- Guest Bloggers

- Islamic Holidays

- Advanced Arabic

- Arabic Alphabet

- Arabic Grammar

- Arabic Lessons

- Arabic Online

- Arabic Phrases

- Arabic Podcasts

- Arabic Words

- Tips & Techniques

- Media Coverage

- Feature Spotlight

- Success Stories

- Teaching Site

- Team SitePod101

- Uncategorized

- Word of the Day

- Immigration, Visas

Copyright © 2024 Innovative Language Learning. All rights reserved. ArabicPod101.com Privacy Policy | Terms of Use . This site is protected by reCAPTCHA and the Google Privacy Policy and Terms of Service apply.

Writing the Rihla: 1355

Ibn Battuta was commanded to "dictate an account of the cities which he had seen in his travel, and of the interesting events which had clung to his memory, and that he should speak of those whom he had met of the rulers of countries, of their distinguished men of learning, and of their pious saints." [From the introduction to The Rihla , transcribed by Ibn Juzayy, 1354.]

Working with Ibn Juzayy on The Rihla in Fez, Morocco

After Ibn Battuta returned to Fez in 1354, the Sultan of Morocco listened to his report on Mali. He also listened to Ibn Battuta's other adventures, and ordered him to stay in Fez. He wanted to have these stories written down for the amusement of his family and others. Travel writing, especially accounts of the Hajj, were a popular form of writing at the time. So Ibn Battuta was commanded to

"dictate an account of the cities which he had seen in his travel, and of the interesting events which had clung to his memory, and that he should speak of those whom he had met of the rulers of countries, of their distinguished men of learning, and of their pious saints." [From the introduction to The Rihla , transcribed by Ibn Juzayy, 1354.]

The Sultan hired a young writer - Ibn Juzayy - the young man Ibn Battuta had met in Granada three years earlier. Ibn Juzayy must have been excited about such a task! He had been fascinated by Ibn Battuta's stories earlier, and as a young writer, this job was one that could earn him respect. He was to put the stories into the proper form of a travel book, called a "rihla." Rihla means "voyage" in Arabic and it was a genre (type) of Arab literature that combined a description of travel (travelogue) with commentary on the people and practices of Islam throughout the Muslim world. Ibn Juzayy's account of Ibn Battuta's trip follows typical conventions for the genre, including sometimes borrowing descriptive language about various locations from similar, earlier travel accounts.

And so began the retelling of his adventures that had begun twenty-nine years before. Ibn Battuta wove his observations and hearsay, history and odds and ends into his story. Ibn Juzayy added poetry here and there, but generally he kept to Ibn Battuta's telling. To fill in gaps in Ibn Battuta's descriptions, Ibn Juzayy borrowed descriptions of Mecca, Medina and Damascus from a twelfth century traveler named Ibn Jubayr, and perhaps descriptions of other places from other travelers, too. This makes it hard to know exactly which parts of the account actually reflect Ibn Battuta's personal experiences, but it was common practice at the time. His book, like many travel accounts, melded his own experience with that of earlier travelers and his own experiences with hearsay from people he met on the road.

Maybe Ibn Battuta exaggerated his own importance to people he met. After all, he was just a traveler with little formal education. In telling the story, perhaps he couldn't get all the details in order and perhaps his memory failed him on some details. One famous biographer of the time had met Ibn Battuta in Granada and said that he was, "purely and simply a liar." But Ibn Battuta had his supporters, too. One advisor to the Sultan in al-Andalus said, "Be careful not to reject such information about the condition of dynasties, because you have not seen such things yourself." And another scholar in Tunisia said, "I know of no person who has journeyed through so many lands as [he did] on his travels, and he was withal generous and welldoing." [Dunn, p. 316.]

When it was finished, The Rihla had little impact upon the Muslim world. However, it was copied by hand and the whole book or shortened versions could be found in some libraries, or carried around by travelers who followed on parts of his trips. It was not until the 19th century that European scholars found some of the Arabic books and translated them into French, German, and then English. Once it was translated the book began to receive the widespread attention it deserves as a record of history.

This is an important sidenote: historical research depends on multi-lingual people who can read texts in one language and translate them into others, thus making information from the past available to wider audiences. Consider all the documents you have ever read from early English history, Greek or Roman history, Chinese or Indian or Aztec history, etc. Every time you encounter an English version of a text in a book or on the internet, it is the result of a diligent multi-lingual scholar who translated it from its original language (possibly an ancient, dead language) into English.

And what happened to Ibn Battuta after he told his story in the palace of the Sultan? He probably got a job as a qadi (judge), but we don't know where. Little is known about this period of his life. Perhaps he married again and fathered more children. Perhaps he entertained scholars and students with his stories, as he had entertained kings, commoners, and holy men on three continents.

Ibn Battuta died in 1368 or 1369. Tour guides in Tangier take tourists to see an unmarked grave that they claim to be his, but no one can confirm it as his final resting place.

This building, in Tangiers, may be Ibn Battuta's tomb. The photograph comes from the blog of a modern traveller - the current version of the type of rihla that Ibn Battuta produced in the 14th century.

This image of the inside of Ibn Battuta's tomb, comes from a different traveller's blog. This person decided to make a trip specifically in the footsteps of Ibn Battuta. Click on the image to read about his experiences.

Today Ibn Battuta is somewhat famous. A crater on the moon is named after him, as is an Internet online matchmaking service for Arab singles! As you see from the image above on the right, his journey has inspired modern people to travel and see the world. Perhaps most appropriately, the airport of Tangier was named for Ibn Battuta - carrying young Moroccan travelers as they begin their own adventures.

Source: Dans - Own work , CC BY-SA 3.0

ARAB 402: Travel Literature in Arabic: Travel Literature

- Introduction

- Arabic Literature

- Travel Literature

- Cartography, geography and space

- Finding Journal Articles

- Citing Sources

- Some Starting Points

- Discussion #1

- Discussion #2

- Discussion #3

- Discussion #4

How is Travel Literature or Travel Writing defined in library catalog?

When organizing collections, libraries have to describe the sources. How a source is described and what classification terms are assigned will determine how search engines find materials and where the sources are located in libraries.

Scope notes of relevant Library of Congress Subject Headings:

- Travel Writing applies to books about writings of travelers. It covers works on the authorship of writings by travelers that are often presented in narrative form or as memoirs

- Travelers' writings covers collections of works written by travelers from several countries

- Travelers' writing + nationality of the travelers covers Collections of works written by travelers from a specific country

- Name of place + Description and Travel covers works on travel to a specific place

- Travel journalism covers works on journalism that focuses on travel and the tourism industry

Some suggested Subject Headings to find travel literature

You may use these LCSH to search the Williams Libraries catalog and Worldcat:

- Arabs -- Travel

- Muslim pilgrims and pilgrimages

- Travelers--[Name of Country]

- Travelers' writings

- Traveler's writings, Arabic

- Visitors, Foreign—[Name of Country]

- Voyages and travels

- Voyages and travels -- [Name of Country]

- [Name of country or state]—Description and travel

More information from the Library of Congress on locating Travel Accounts.

What about working with keywords?

When conducting research, you need to combine search strategies based on keywords and search strategies based on LC Subject Headings.

Keywords: When we think of travel writing terms such as "travel accounts ", " travelogs ", " travel diaries" may come to mind. These terms can be used a search keywords, they will retrieve materials that use these specific terms. But, these keyword searches will not retrieve materials that are thematically related but use a different terminology.

As you read relevant materials and start researching, pay attention to:

- the terminology used by scholars (different disciplines use different terminology)

- all the aspects of a topic. For examples, in reading Daniel Newman Arabic Travel Writing, you learn about the reasons that Arabs have travelled throughout history. One reason is religion. Knowing that, you can then craft keyword based searches combining travel and Islam. This search brings up sources related to the Arabic travel writing.

Subject Headings : Are assigned to materials by librarians with the goal of transcending keywords and creating clusters of related sources. Using LCSH enables you to perform a more comprehensive searches.

Where are sources located in the library?

Travel writing is classed in a variety of location in the LC Classification System. You may find sources in:

- the general range for Special voyages and travel: G368.2-503

- the place the author traveled to

- some aspect of the author's identity (e.g. Wonderlands : good gay travel writing , is classed in the gender studies class: HQ)

- some aspect of the journey itself (e.g. , V isiting the Shakers, 1850-1899 is classed in the Religion section: BX)

- << Previous: Arabic Literature

- Next: Cartography, geography and space >>

- Last Updated: Mar 22, 2024 12:00 PM

- URL: https://libguides.williams.edu/ARAB402

- NONFICTION BOOKS

- BEST NONFICTION 2023

- BEST NONFICTION 2024

- Historical Biographies

- The Best Memoirs and Autobiographies

- Philosophical Biographies

- World War 2

- World History

- American History

- British History

- Chinese History

- Russian History

- Ancient History (up to 500)

- Medieval History (500-1400)

- Military History

- Art History

- Travel Books

- Ancient Philosophy

- Contemporary Philosophy

- Ethics & Moral Philosophy

- Great Philosophers

- Social & Political Philosophy

- Classical Studies

- New Science Books

- Maths & Statistics

- Popular Science

- Physics Books

- Climate Change Books

- How to Write

- English Grammar & Usage

- Books for Learning Languages

- Linguistics

- Political Ideologies

- Foreign Policy & International Relations

- American Politics

- British Politics

- Religious History Books

- Mental Health

- Neuroscience

- Child Psychology

- Film & Cinema

- Opera & Classical Music

- Behavioural Economics

- Development Economics

- Economic History

- Financial Crisis

- World Economies

- Investing Books

- Artificial Intelligence/AI Books

- Data Science Books

- Sex & Sexuality

- Death & Dying

- Food & Cooking

- Sports, Games & Hobbies

- FICTION BOOKS

- BEST NOVELS 2024

- BEST FICTION 2023

- New Literary Fiction

- World Literature

- Literary Criticism

- Literary Figures

- Classic English Literature

- American Literature

- Comics & Graphic Novels

- Fairy Tales & Mythology

- Historical Fiction

- Crime Novels

- Science Fiction

- Short Stories

- South Africa

- United States

- Arctic & Antarctica

- Afghanistan

- Myanmar (Formerly Burma)

- Netherlands

- Kids Recommend Books for Kids

- High School Teachers Recommendations

- Prizewinning Kids' Books

- Popular Series Books for Kids

- BEST BOOKS FOR KIDS (ALL AGES)

- Ages Baby-2

- Books for Teens and Young Adults

- THE BEST SCIENCE BOOKS FOR KIDS

- BEST KIDS' BOOKS OF 2023

- BEST BOOKS FOR TEENS OF 2023

- Best Audiobooks for Kids

- Environment

- Best Books for Teens of 2023

- Best Kids' Books of 2023

- Political Novels

- New History Books

- New Historical Fiction

- New Biography

- New Memoirs

- New World Literature

- New Economics Books

- New Climate Books

- New Math Books

- New Philosophy Books

- New Psychology Books

- New Physics Books

- THE BEST AUDIOBOOKS

- Actors Read Great Books

- Books Narrated by Their Authors

- Best Audiobook Thrillers

- Best History Audiobooks

- Nobel Literature Prize

- Booker Prize (fiction)

- Baillie Gifford Prize (nonfiction)

- Financial Times (nonfiction)

- Wolfson Prize (history)

- Royal Society (science)

- Pushkin House Prize (Russia)

- Walter Scott Prize (historical fiction)

- Arthur C Clarke Prize (sci fi)

- The Hugos (sci fi & fantasy)

- Audie Awards (audiobooks)

Make Your Own List

Nonfiction Books » Travel

Books about travelling in the muslim world, recommended by tim mackintosh-smith.

Arabs: A 3,000 Year History of Peoples, Tribes and Empires by Tim Mackintosh-Smith

Author and Arabist Tim Mackintosh-Smith tells us about the rich tradition in Islam of travelling to gain knowledge, and directs us towards some of those, both Western and Arab, who’ve inspired with their tales of life on the road.

The Travels of Ibn Battutah by Ibn Battutah (edited by Tim Mackintosh-Smith)

The Road to Oxiana by Robert Byron

A Year Amongst the Persians by Edward G Browne

The Sindbad Voyage by Tim Severin

Night and Horses and the Desert by Robert Irwin (editor)

1 The Travels of Ibn Battutah by Ibn Battutah (edited by Tim Mackintosh-Smith)

2 the road to oxiana by robert byron, 3 a year amongst the persians by edward g browne, 4 the sindbad voyage by tim severin, 5 night and horses and the desert by robert irwin (editor).

What makes a great travel writer?

Should travel writing – excluding travel guides – be taken literally, or should readers accept a degree of exaggeration and embellishment in order for a good story to be told? I’m thinking in particular of Bruce Chatwin, who made up significant bits of The Songlines to make the story “real”. Is that acceptable?

I definitely don’t think you should tell fibs and make stuff up. But readers almost expect that you will tell lies. I can give you an example. In my Yemen book , I write about meeting this little boy in the street who’s kicking a football and he’s wearing my prep school blazer. People would say: “Was that really true or did you make it up?” It was absolutely true. In fact, I wrote about it quite carefully so that I didn’t actually say it was my very own prep school blazer. But people automatically read it as saying that it was my very own blazer, which couldn’t possibly be true. That’s the kind of expectation people have of travel writing.

Probably the best simile for what you have to do is like when you make a TV programme – you play around with the colours afterwards, you heighten some and dull others down to make it look better. You don’t end up telling fibs or anything, but you do heighten the colours. Another example, which I owned up to, is in my India book [ The Hall of a Thousand Columns ] where there’s a chapter on [the town of] Aligarh. It comes across as if I made a single, discrete visit, when in fact I went there five or six times over two years, but I connected them together. If you say everything that happens to you and in exactly the order it happened, nobody would want to read you. You do have to edit, to cut and splice, to do the montage. It’s a bit like film editing.

Travel for Muslims is a religious duty, as believers are expected to go to Mecca for the hajj at least once in their lifetime. Do you think there is a richer tradition of travel writing amongst Muslims?

Absolutely. Very much so among Arabs in particular. There is a word in Arabic “ rihlah” – it’s both a journey and also a book about a journey. You can go back a long way, to the time of the Abbasid caliphs around the ninth century, and you get people writing accounts of their journeys. A bit later you had people like Ibn Jubayr, who was 12th century. He was the paragon of Arabic travel writing. The Quran encourages people to travel and gain knowledge. Travel for knowledge is a very big thing in Islam. There’s a famous saying of the prophet Mohammed: “Seek knowledge even if you have to go to China.”

Today, we live in a world of instant and easy communication. Has it become harder for travel writers to capture the attention and the imagination of their audience?

I talked a bit about this in my last book apropos [Moroccan 14th century traveller] Ibn Battutah going to China and getting stuff completely wrong. For example, he said that the emperor had been killed and there was a funeral. That was nonsense as he lived for another 25 years. Then I thought, he didn’t have Google to check things on; he didn’t have guidebooks – he would have been in China in a complete blizzard of not knowing anything. But his main job was to impart information. Now we can get our information from so many different sources and so easily that that side of travel writing isn’t there so much. I try to differentiate information and knowledge. I think what you can impart as a travel writer is knowledge. You can impart insights and a narrative which you can’t get on the Internet or in a guidebook.

Just before we move on to your books, I would like to touch on the fact that you live in Yemen , a country which the British Foreign Office recommends all its nationals leave immediately. I trust you won’t be coming home soon, but I wonder if you would tell us about why you live there and whether the current wave of instability in the country can be given a broader historical context?

I live in Yemen because I love it. I really do love it. I have lots of good friends here – some very special friends who are like family. In fact, I have just done an interview on [local] TV in which I was effectively saying that despite all the crises and all the problems, I still do love the place and I always will. The country is not just the leader who happens to be in power at the time, messing things up as like as not. It’s the whole cultural past and the future as well. This is what I like. You must look before and in front of the moment that you are in. Inshallah [God willing], it has a great future somewhere along the line.

We’ve broken all our rules by allowing you to include in your list a book that you have contributed to, but it is the most readily available edition. Can you tell us more about Ibn Battutah and his extraordinary travels?

I couldn’t not include him. His editor Ibn Juzayy says towards the end of the book that Ibn Battutah is “the traveller of the Arabs and if anyone says he is a traveller of this ummah [Islamic community], he would not be wrong”. That actually stands today. In a sense he hasn’t been bettered since that time [the 14th century]. The complete diversity of the Muslim world was put on the axis of a book by Ibn Battutah. Nobody afterwards could really do better. He is the traveller of the Islamic world.

He was born in 1304. In 1325, when he was 21, he sets out on a pilgrimage to Mecca. He starts from Tangiers in Morocco, so it’s a long way from there to Mecca. It’s almost as far as you can go in the Arab world. Like other people doing that pilgrimage from his background, which was an educated background of judges and scholars, he would have hoped to do some studies along the way, probably in Cairo or Damascus, which is indeed what he did. But unlike most of these other people, he really got the travel bug. I think there are a number of reasons for this. One is that he realised that he could make money and get jobs in the Islamic world, especially in areas that were newly Islamised or its leaders were newly Islamised, like the ruler of India. Ibn Battutah thought, “I can get a job there,” being a card-carrying Arab Muslim scholar. So he went further than the pilgrimage, partly to get jobs to make money and to hobnob with sultans, and partly because he had this total fascination with the world of Islamic mysticism – Sufis, and particularly Sufi holy men. So he was really trying to collect sultans to make money from them, and he was trying to collect Sufi holy men, both dead and alive, as you could visit a tomb and be deemed to have visited that person, and collect their barakah [blessing]. So, he travelled for these different reasons and he kind of went on and on and on.

If you read this book, it seems quite chaotic, but there is an underlying structure to it. I think there are two elements to this structure. When he is in Egypt he has this dream, which is interpreted by a holy man who says: “You will go to these different countries.” Another holy man he meets predicts he will meet his spiritual brothers in India and China. So part of the structure is fulfilling his fate, which has already been predicted. Another part of the structure is he talks quite early on about the seven great kings of the known world and they are obviously his ruler in Morocco, because he’s got to say nice things about him, and the Mamluk Sultan of Egypt and Syria, the Sultan of Delhi and then the four Mongol cousins – the Khan of the Golden Horde, the ruler of Iran and Iraq, the ruler of central Asia and the Chinese Emperor. All of those were Muslims, except for the Emperor of China. I think possibly what happened, and this is speculation, is that he sort of realised he didn’t actually get to see the Emperor of China so he added on a seventh great king who was a Muslim, and he was the Emperor of Mali, which was this great West African empire. And so he collected these seven great kings and uses them as a hook and that I think is the deep structure of his book.

At some point he realised he was surfing this huge wave of Islam and that he could actually be the one who wrote about the Islamic world – his rihlah could be the rihlah to end all rihlahs. I think he probably realised that consciously at some point.

Could you tell us where he got to and how long his journey lasted?

He spent 29 years travelling overall. I’ll tell you the outer limits of his journey. He started in Morocco and he covered most of the known world between the middle of the River Volga to the north, down to almost what is now the border of Mozambique in the south; east as far as Guangzhou in China, and west, we don’t know quite how far, but probably not quite as far as Senegal but getting that way. If you think of the known world of his day, it almost sits within those outer limits. It is extraordinary.

His account of his journey was never that popular in the 14th century, compared with, say, the writing of Ibn Jubayr. Why was that?

In his introduction to your next book, Road to Oxiana , Bruce Chatwin describes it as a “sacred text, beyond criticism”. Would you agree?

I recently wrote about this book and hooked what I wrote on what Chatwin said about it – that it was a sacred text – and what Wilfred Thesiger said, which was that it was a lot of nonsense. I think you can reconcile these views. It’s actually why I like the book. It’s sacred nonsense, or Robert Byron is a holy fool, if that makes sense. It’s nonsense because he sort of explodes the usual narrative of the travel book – the narrative itinerary where you go from A to B, B to C and so on. Byron is all over the shop. I think if you read his contents page, it tells you he goes to Tehran seven times and he goes to Persia and then Afghanistan and then back to Persia and then Afghanistan and Persia again and he ends up in India and then he’s back in Wiltshire [in the UK]. So it really is all over the place. So it is nonsensical in that way. But the reason that somebody like Chatwin thought it was sacred was above all because of his looking. This is what Byron does and he’s absolutely brilliant at it.

He’s looking at buildings isn’t he, searching for the roots of Islamic architecture?

Yes, he’s looking at Islamic architecture. The reason I chose it as one of my five Muslim world travel books, even though he isn’t an Islamicist or Arabist or anything, is because he once said that to travel in the Islamic world is to look at a close cousin. Travelling to India and Tibet he said was to discover a new and wholly unconnected world. So, it’s really the way that he’s looking at Islamic architecture and Islamic rationalism. He is drawing subtle parallels between the place he starts with, which is Venice – he goes to the Veneto and looks at Palladio’s Villa “La Malcontenta”, the masterpiece of Palladian rationalism – and places like Isfahan and the great tomb tower in Iran, and he is covertly making his point that Islam and the West are sharers in this rationalism. And that’s really why I am so inspired by him as someone who travels in the Islamic world and looks at Islamic buildings. It’s why Chatwin called him sacred, I think. He’s sacred, not in a secular sense, but a humanist sense. He’s trying to tease out what makes humans reasonable, rational and capable of producing great works of art. He teases this out beautifully and he draws the parallel that what we have in Europe and what we care about and love so much you can find in the Islamic world also. It’s a tremendously important point.

In Britain, Byron was very much a “Brideshead” character – a camp aesthete, gossipy and belligerent. He becomes almost a better person when he travelled.

Your third book, A Year Amongst the Persians , was written at the end of the 19th century by Edward Granville Browne, a British Arabic professor at Cambridge. Why did you choose it?

It’s a good book to segue on to after Byron as they both visit Persia. But Byron is most of all into looking and Browne is most of all into ideas. He considers ideas in a huge way. It’s a book that’s very much an anthology of ideas.

Browne studies Persian at Cambridge and goes off to Persia for a year and flits around from place to place and observes the ruling Qajar dynasty of the time. He talks interestingly about the tensions between the Qajars – who were Turkic – and the Aryans, in Persian history. The bit that I love the most is when he is in Kerman where he gets into this world of ideas. He gets in with these dervishes, who are these quite extreme Sufis. He talks about being intoxicated by opium smoke and mysticism. He has this weird experience. He gets ophthalmia when he’s in Kerman and somebody says the best way to counteract the pain is by smoking opium. So he gets into this complete reliance on opium – he calls it the “poppy wizard”. It turns into this trippy, hippy experience. Remember we’re back in the 1880s, not in the 1960s, when it’s all about mysticism and opium smoke.

He was very sympathetic towards Persia and its people. It could be said to be a bit of a departure from much of the Orientalist literature being written at the time.

He, like Byron, was a supremely civilised man. I think, if I remember right, somebody advised him that if he had private means, the best way you can indulge a penchant for civilisation is by going off and indulging in Oriental studies. He was one of these supremely civilised Orientalists, quite a rare breed. There is a sheer intoxication not just with mysticism, opium smoke and metaphysics but also with words. In a sense his book doubles as an anthology of Persian poetry. This is what he went on to be most famous for, the literary history of Persia. He was a professor of Arabic at Cambridge but I think only because there wasn’t a professorship of Persian at the time. He really was a Persianist before he was an Arabist.

I wouldn’t want to put readers off who are not into the mysticism, metaphysics, opium and Persian poetry because it’s also in places, like Byron’s, a deeply funny book. He says one thing about the Persians is that they share with us a sense of the ludicrous. A lovely example of this, which chimes so much with my sense of humour, is where he recalls a joke which is told about Isfahanis, who are supposed to be very miserly. He says they say the Isfahanis are so miserly they put their cheese in a glass bottle and rub their bread on the outside of the bottle. He goes on and says one day a merchant in Isfahan caught his apprentice looking hungrily at the cheese in the glass bottle and said “Isn’t dried bread good enough for you?” Something like that rings a humorous bell with us and that’s part of what makes his book so lovely.

Tim Severin is famous for retracing legendary journeys of historical characters. What can you tell us about his book The Sindbad Voyage ?

I chose it because it’s got boys’ stuff in it and I’m quite into boys’ stuff. It’s about how you put things together, how you build things. It’s about this journey from Muscat [in Oman] to Guangzhou or Canton in China. A substantial part of the book is about his research of how you make a sewn boat or ship, which is what his boat was. Not that the boat was made of cloth, but the planks, rather than being nailed together, have holes put in them and big cross stitches are used to pull them together. There are various reasons why people say these sewn boats were used in the Indian Ocean for thousands of years. Perhaps they withstand collisions against reefs better or perhaps people didn’t have access to nails. But whatever the reason, people used this technique of sewing boats which had been completely forgotten in Oman, but is still used in Kerala in southwest India. And so Severin goes off to India and researches how you actually make these boats, picks up a load of guys and brings them back to Muscat to make this boat using methods from a thousand years ago.

I’m into how to make things and how to restore things and I found the story of how they researched and made the boat absolutely fascinating. On top of that you have the voyage and all the adventures and derring-do – the mast breaks, they sail through storms and so on. It’s really like reading the stories of Sinbad or the stories of Al-Ramhurmuzi, an Arabian sea captain from the 10th century. It’s fascinating from the point of view of the building and the journey and it’s like travelling back in time and that’s why I love it.

Night and Horses and the Desert by Robert Irwin – what does this anthology of Arabic literature tell us about travel?

It’s been said before by others, but I think reading is travel and travel is reading. As a travel writer I’m very conscious that they are twins or different sides of the same coin. In Arabic, the word for travelling is safar and from the same Arabic root you get the word sifr , meaning an old-fashioned volume of a book or a scroll. The reason they come from the same root is because when you travel, you are unrolling the world beneath your feet. And when you are unrolling a scroll you are unrolling a scroll beneath your gaze. So there is a very close relationship between reading and travelling.

Irwin does have quite a lot of travelling in the book. His title itself comes from one of the great lines of Arabic poetry by the great poet Al-Mutanabbi. I am very into Arabic verse and the meters of Arabic verse are supposed by some to have come from the different paces of camels.

It’s loosely based on a journey through the desert, isn’t it?

The classical Arabic ode really describes a journey. The meters themselves in Arabic poetry are supposed by some to have come from the trotting, galloping, walking and ambling of camels and horses. Arabic literature and particularly poetry are absolutely suffused with motion and travel. You could say that if a piece of literature moves you in a metaphorical sense it can move you almost physically. It can move you to different places and move you to different times. I talked before about time travel, but I think reading a book like this is the closest you can get to time travel. I think you can learn a lot more about the Arab and Islamic world from a book like this than you can from reading political narrative history.

Can you give us a little more on the contents of the book?

It’s classical Arabic literature and he takes us from pre-Islamic poetry in the sixth century to the 16th century. He doesn’t encroach on later times. He’s really looking at the great period of classical Arabic. He divides his book into the pre-Islamic period, then the courtly times of the Abbasid caliphs, and then there is a long chapter on the wandering scholars, which shows the connection between travel and literature. The last chapter is about the Mamluk period and the Turkic people taking over, and the Arabic literature this period generated. I think he says in the book that, “You may think I have got a lot of poetry, but I haven’t got enough.” Poetry is the life and soul of Arabic literature. But he’s got a good mix of poetry and prose. His commentary that joins it together is superbly balanced. There is no better anthology of Arabic literature. It’s a book that I wish I had compiled myself.

February 13, 2012

Five Books aims to keep its book recommendations and interviews up to date. If you are the interviewee and would like to update your choice of books (or even just what you say about them) please email us at [email protected]

Support Five Books

Five Books interviews are expensive to produce. If you've enjoyed this interview, please support us by donating a small amount .

Tim Mackintosh-Smith

Tim Mackintosh-Smith is an Arabist, traveller, writer and lecturer. He studied at Oxford University and lives in San'a, the Yemeni capital. He is one of the foremost scholars of 14th-century Moroccan traveller, Ibn Battutah, and in 2011 was named by Newsweek as one of the finest twelve travel writers of the last hundred years.

We ask experts to recommend the five best books in their subject and explain their selection in an interview.

This site has an archive of more than one thousand seven hundred interviews, or eight thousand book recommendations. We publish at least two new interviews per week.

Five Books participates in the Amazon Associate program and earns money from qualifying purchases.

© Five Books 2024

Library of Arabic Literature

- NYU Abu Dhabi

- NYUAD Institute

- Book Supplements

- Arabic PDFs

Reading Two Arabic Travel Books : A Guide for Beginner Students of Arabic

In this blog post, Adam Bremer-McCollum describes his experience teaching an Arabic reading course at the University of Notre Dame, for which students read selections from Two Arabic Travel Books by Abū Zayd al-Sīrāfī and Ibn Faḍlān. He explains his approach to teaching (and learning) pre-modern Arabic and offers some tips and advice for beginning students.

“Arabic Script” by Nidhi Ranganath. CC BY-SA 4.0 via Wikimedia Commons.

We live in a vast and overwhelming world, and one experience that can feel especially overwhelming is trying to learn a new language. In his book The Doors of Perception , the English writer and philosopher Aldous Huxley famously used the image of a reducing valve to explain how the human brain copes with overwhelming sensory input by selectively ignoring some things. Language learners can also use this concept of a “reducing valve” to help them approach new texts. There’s so much possibility in a written text — how to say it, how parts are connected, what individual and joined words may mean — that readers will benefit from tools to help focus the incoming flood of words, forms, and meanings. For Arabic, aids like thorough vocalization and a glossary reduce the noise of additional possibilities and guide readers to the correct pronunciations and meanings as they read a text.

In my experience, both as a learner and a teacher, thorough and generous grammatical and lexical guidance lays a solid foundation for a future of reading: once you have read and re-read several guided readings, you know ins and outs of real texts, vocabulary in context rather than just from lists, and at least something of the more common grammar-marking vocalic patterns. You can get to know Arabic by reading Arabic, with quick references as necessary to a short, focused glossary when needed, rather than spending your time at this early stage combing through big dictionaries: you’ll be doing plenty of that later with your own texts!

Example of Judeo-Arabic: Fragment from the Cairo Genizah. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons .

I recently taught an Arabic reading course for students relatively new to Arabic. The students in the course had all studied other pre-modern literary languages (e.g. Latin, Greek, Syriac, Coptic, Ottoman Turkish), some with me. In the previous semester, they had taken an introductory Arabic grammar course, including not only examples from conventional classical Arabic but also non-standard varieties like Judeo-Arabic, Arabic in Greek script, Garšūnī (Arabic in Syriac script), and Arabic in Coptic script. The point here was both to de-center any idea of a monolithic “classical” Arabic with its accompanying notions of gatekeeping, and to see — in terms of phonology, grammar, script, literature, and more — how rich and diverse Arabic is and has long been.

For the reading course, I chose a few texts that were both entertaining and not especially difficult in terms of style or vocabulary. The texts we read included excerpts from each of the two works included in Two Arabic Travel Books: Abū Zayd al-Sīrāfī, Accounts of China and India, and Ibn Faḍlān , Mission to the Volga , edited by Tim Mackintosh-Smith and James E. Montgomery: descriptions of a king’s death by suicide (§2.8.1), how men pee in China (§2.9.6), and on pearls (§2.17.1-2) in the former; and sections on cold weather in al-Ǧurǧānīya (§10-12), entering the lands of the Turks (§15-16), and the Ġuzzīya tribe (§18-19) in the latter. Over the course of the semester, we also read chapters from an Arabic version of the book of Jonah , Burzoy’s voyage (François de Blois, Burzōy’s Voyage to India ) , excerpts from al-Maqrīzī’s Ḫiṭaṭ on cannabis (from de Sacy’s Chrestomathie arabe ), and twelve short verse selections on cannabis culled from al-Badrī and others. All of these were chosen because they were entertaining or humorous in some way, or because they might touch on things we talk about today (e.g. comparing cannabis and alcohol). In addition, these texts are just a few of many possible choices that show how wide a range of topics Arabic literature can cover.

For each of the selections, I re-typed and thoroughly vocalized them. Editions of Arabic texts are generally not vocalized — usually the case, too, with Hebrew and Aramaic texts. However viable or not this situation is for people well acquainted with Arabic grammar and lexicon, it leaves learners in the lurch. It’s not ideal for learning when students ignore vowel patterns because they’re not always written, nor is it an efficient use of time for beginning students to shoulder the full burden of figuring them out. Amply vocalized texts are valuable and time-saving reading material for learners because they highlight the actual, fully specified forms in the text at hand, rather than forcing students to take into full consideration every other root-and-pattern possibility.

As an example of the documents I prepared for the class, here is the PDF with selections from Accounts of China and India and Mission to the Volga and glossary . You’ll notice that the glossary is almost twice as long as the text itself.

In my class, the regular method was for students to prepare the assigned texts beforehand, with attention to the vocalized forms and related grammar, and relying heavily on the glossary. We would then go through all or most of the text together in class. We also did occasional cold readings of unprepared (but still vocalized) texts in class. Since students had to devote less time to checking vowel patterns, thinking through the related aspects of grammar or lexicon, and flipping through dictionaries, which can be a deflating reality for less experienced students when they come to “real” texts, we could focus on the actual texts in front of us and discuss them together on the same terms, with a lot less grammatical and lexical uncertainty thanks to the supplied text and glossary. These lexical and vocalic aids allow more time for discussion of the text’s content, on the one hand, and on the other, for discussing how to read and study Arabic texts when you won’t have a ready-made glossary and vocalized text, i.e. most of the time!

Is it possible to learn to read Arabic (or some other language) without the help of vocalization and a glossary? Of course. But what’s the point of early-stage language students having a teacher if the teacher is just throwing bare texts to students and laying the initial burden of reading and understanding on them? “Sink-or-swim” as a model for learning to read texts in other languages may work for some students, but even then a method with a liberal dose of extra help won’t hurt, and they may even learn more. Expertise on the part of the teacher is great, of course, but it’s much better when side-by-side with generosity.

Reader’s texts like the ones presented here can focus the flood of linguistic possibility into a manageable stream. This approach acknowledges that a newer student to Arabic doesn’t automatically know or rightly infer the vowels in a regular unvocalized text, nor are they going to get through a page of Arabic without frequent recourse to the dictionary. Some of this — looking up and re-remembering patterns, grammar, meanings — is just part of language-learning, of course, but the more teachers can offer students opportunities to read a variety of texts supported by robust grammatical and lexical helps, the more Arabic they can read, appreciate, and get to know in their own ways.

Adam Bremer-McCollum is a translator, teacher/tutor, language consultant, and writer. He has taught languages and literatures of late antiquity, including Syriac, Arabic, Armenian, Coptic, and Hebrew, at the University of Notre Dame.

Essential Arabic Phrases For Travel – Speak Freely While Traveling

Some of the best experiences in life are had when one travels abroad. Indeed, when you travel to another country and immerse yourself in its culture, it can be fun and exciting. However, speaking that country’s language, even if it’s just a few words, can offer you an even richer experience. For instance, while poring over those brochures of Petra, did you ever think about learning Arabic phrases for travel to make your trip to Jordan even more rewarding?

Listen to the locals

After all, isn’t it the locals who can tell you the best places to eat, sleep, and sightsee? Certainly, learning more than just how to say “hello” in Dubai offers tourists opportunities they’d never find in a guidebook. What’s more, when you travel in Arabic speaking countries , you’ll find most locals are friendly and happy to help.

This is especially true when some knows what to say in Arabic when someone is traveling. This is because Arabs really admire someone who attempts to speak their language. You see, they, too, realize that Arabic isn’t the easiest language to learn. Nevertheless, they’ll respect your effort. Besides that, when you speak to a native speaker of Arabic, you’ll be improving your Arabic language skills as well. Thus, you’ll be ensuring a richer and more rewarding experience no matter which Arabic speaking country you decide to travel to.

Essential Arabic phrases for travel

The Arabic word for travel is السفر / alsafar . Now that you’ve learn your first travel-related word in Arabic, let’s get you started on the rest of your journey.

Here’s a list of Arabic words related to travel to get you started:

In conclusion.

Ready to learn more? Well, what if we told you that you can learn Arabic anytime, anywhere before you even step on a plane? It’s true! With the Kaleela Arabic learning app, you’ll learn real Arabic dialects in courses designed by native Arabic speakers. Our app takes you step-by-step from learning the Arabic alphabet to using real-world phrases in conversations all at your own pace! Students and travelers alike highly recommended the Kaleela Arabic learning app! Best of all! Download it now and start speaking Arabic today, only from Kaleela.

Kaleela – Learn Arabic the Right Way!

- Meaningful Arabic Quotes That’ll Get You Through Your Day

- Love Is In The Air – Express Your Love With These Sweet Arabic Words

- The Arabic Alphabet – Tips On How To Pronounce The Difficult Letters

- Arab Times – Telling The Time In Arabic

- Basic Words in Arabic – The Most Commonly Used

- Syrian Dishes – 10 Of Syria’s Most Delicious Main Dishes

- Animals In Arabic Language – Names And Special Meanings

- Arabic Prepositions – Commonly Used In Everyday Conversation

- Days In Arabic – Learn To Say The Days Of The Week

- A Look At Capital Cities Of Arab Countries – A Complete List

Get updates & special offers from kaleela

Voice speed

Text translation, source text, translation results, document translation, drag and drop.

Website translation

Enter a URL

Image translation

Introduction

Arabic phrases for giving directions, arabic phrases for transportation, arabic phrases for accommodations, miscellaneous arabic words and phrases, scenario 1: exploring the city, scenario 2: at the hotel, scenario 3: at the restaurant, scenario 4: at the tourist information center.

Help us share the article:

Traveling To an Arab Country? Here are 25 Excellent Arabic Phrases to Guide You

by Dania Ghraoui

24 Jul, 2023 . 6 mins read

Learning Tips

Hello, my dear Arabic language learners. The first thing that you might think about when traveling to an Arab country or countries that speak Arabic is the ability to communicate with the locals. This is vital, as it ensures safety and comfort during the trip. What’s more, the ability to articulate some essential phrases in the local language grants us the confidence to move around our temporary residence and remain highly functional. Whether the trip is for work, leisure, or studying, conversing in the local language can significantly enhance our overall experience.

And because Arabic is a language rich with history, culture, and diversity, your journey could be even more rewarding. As you’re exploring the historical sites of Egypt, the luxurious cityscape of Dubai, or the cultural wonders of Morocco, you’ll find that a basic understanding of Arabic is immensely helpful. From asking for directions, and haggling at a local market, to ordering food at a restaurant, your attempts to communicate in Arabic can open doors, bring smiles, and foster mutual respect.

In this post, we will introduce you to 25 Arabic phrases to use when you travel to an Arab country. These phrases have been carefully selected to cover various situations, including directions, transportation, accommodations, dining, etc. By learning and using these Arabic words and phrases, you will not only be able to navigate the Arabic-speaking world more easily but also enrich your cultural experience and make lasting memories.

In addition to providing you with essential Arabic phrases, this blog also includes real-life scenarios to help you apply what you’ve learned and see them in context. These scenarios, set in common travel situations, are designed to offer practical demonstrations of how and when to use the phrases. Whether you’re trying to find your way in a bustling city, ordering a meal in a restaurant, or checking into a hotel, these scenarios will give you a realistic insight into navigating the Arabic-speaking world. The aim is to ensure that you’re not only memorizing these phrases but also understanding their context, thereby enhancing your confidence to communicate effectively during your travels.

So, are you ready? Let’s start by looking at 25 essential Arabic words and phrases for travel , including vocabulary for directions, transportation, accommodations, and more.

When you’re in a new place, it’s important to be able to ask for directions. Here are some Arabic phrases that can help you navigate your way around:

Getting around in an Arabic-speaking country can be an adventure in itself. Here are some Arabic words and phrases related to transportation:

Whether you’re staying in a hotel, hostel, or guesthouse, here are some Arabic words and phrases related to accommodations:

Here are some additional Arabic words and phrases that can be useful for travelers:

In the following two scenarios, we’ll explore some common situations a traveler may encounter while visiting an Arabic-speaking country. In Scenario 1 , our tourist interacts with a local resident to get information about public transportation and the city’s layout. In Scenario 2 , the tourist checks into a hotel, inquiring about room availability and payment options. In Scenario 3 , our tourist is dining at a restaurant. They discuss dietary preferences and ask about the menu with a waiter, and in Scenario 4 , our traveler visits a tourist information center. They ask for a city map and inquire about a specific location.

These scenarios demonstrate the practical use of the essential Arabic phrases and vocabulary we learned for travelers in real-life situations .

Real-Life Arabic

Tourist: مرحبا!ً كم تبعد المدينة من هنا؟

(Hello! How far is the city from here?)

Local: تبعد المدينة حوالي خَمسَةَ كيلومترات من هنا. هل ترغب في السّير على الأقدام أو استخدام وسائل النّقل العامّ؟

(The city is about 5 kilometers from here. Do you prefer to walk or use public transportation?)

Tourist: أفضل استخدام وسائل النّقل العامّ. مِن أين يمكنني شراء تذاكر الحافلة؟

(I prefer to use public transportation. Where can I buy bus tickets?)

Local: يمكنك شراء تذاكر الحافلة من أجهزة البيع الآلي في محطة الحافلات أو داخل الحافلة نفسها.

(You can buy bus tickets from vending machines at the bus station or inside the bus itself.)

Tourist: شكراً! هل يمكنني الحصول على خريطة المدينة؟

(Thank you! Can I get a map of the city?)

Local: بالطّبع! يمكنك الحصول على خريطة مجّانية من مكتب السّياحة أو تنزيل تطبيق على هاتفك الذكي.

(Of course! You can get a free map from the tourism office or download an app on your smartphone).

Tourist: مرحباً! أريد غرفة فندقيّة لمدة ثلاثة أيام. هل لديكم غرف متاحة؟

(Hello! I want a hotel room for three days. Do you have available rooms?)

Receptionist: نعم، لدينا غرف متاحة. هل تفضّل غرفةً مزدوجةً أم مفردةً؟

(Yes, we have available rooms. Do you prefer a double or a single room?)

Tourist: أريد غرفة مزدوجةً من فضلك. هل يمكنني استخدام بطاقة الائتمان هنا؟

(I want a double room, please. Can I use my credit card here?)

Receptionist: بالطّبع! يمكنك استخدام بطاقة الائتمان للدّفع.

(Of course! You can use your credit card for payment.)

Tourist: ما هو رقم الهاتف الخاصّ بالفندق؟

(What is the hotel’s phone number?)

Receptionist: رقم الهاتف الخاصّ بالفندق هو 123-456-7890. إذا كنت بحاجة إلى أي مساعدة أخرى، لا تتردد في الاتصال بنا.

(The hotel’s phone number is 123-456-7890. If you need any further assistance, please don’t hesitate to contact us.)

Tourist: شكراً لمساعدتك!

(Thank you for your help!)

Receptionist: وداعاً ! استمتع بإقامتك!

(Goodbye! Enjoy your stay! )

Tourist: مرحبا! أنا نباتي. هل لديكم خيارات نباتية؟

(Hello! I’m a vegetarian. Do you have vegetarian options?)

Waiter: نعم، لدينا العديد من الخيارات النباتية. يمكنك الاطلاع على القائمة هنا.

(Yes, we have many vegetarian options. You can check the menu here.)

Tourist: هل هذا الطبق حار؟

(Is this dish spicy?)

Waiter: لا، هذا الطبق ليس حارًا.

(No, this dish is not spicy.)

Tourist: رائع! أود طاولة لشخصين، من فضلك.

(Great! I’d like a table for two, please.)

Waiter: بالطبع، تفضل.

(Of course, right this way.)

Tourist: مرحبا! هل يمكنني الحصول على خريطة المدينة؟

(Hello! Can I get a map of the city?)

Information Officer: بالطبع! ها هي خريطة المدينة. هل تحتاج إلى مساعدة في تحديد المواقع؟

(Of course! Here is the city map. Do you need help identifying the locations?)

Tourist: نعم، من فضلك. أين المتحف الوطني؟

(Yes, please. Where is the National Museum?)

Information Officer: إنه في الجزء الشرقي من المدينة، يمكنك استخدام الخريطة للوصول إليه.

(It’s in the eastern part of the city. You can use the map to get there.)

We hope this excellent collection of Arabic travel words and phrases has been helpful. We’re wrapping up for today, dear learners, and I truly hope you’ve found our journey through these Arabic travel phrases and real-life scenarios valuable. You know, these words and phrases are more than just tools for communication – they’re your keys to connecting with the people and culture of the Arabic-speaking world.

Speaking even a little bit of the local language can make your travel experiences richer and more memorable. And trust me, locals always appreciate it when visitors try to speak their language, even if it’s just a few words or phrases.

So, keep practicing these phrases – they’re your first steps into the beautiful world of the Arabic language. And remember, there’s so much more to discover beyond these basics.

As you set off on your travels, remember to stay curious, enjoy every moment, and embrace the joy of learning a new language. And above all, have a wonderful journey. Wishing you all safe travels, or as we say in Arabic, رحلة سعيدة – ‘Happy Journey’!

Now, to assist you further in your Arabic language journey, I’m excited to share with you a comprehensive planner we’ve created. It has a 30-page worksheet complemented by over 200 exercises and activities designed to enhance your grasp of the Arabic language. This resource is an excellent companion to your studies and will provide you with structured practice to help you retain and apply what you’ve learned.

https://www.alifbee.app/planner

Why Learn Arabic? 8 Benefits to Increasing Your Knowledge of Arabic Language

20 Jul, 2023 . 6 mins read

Arabic Greetings: 10 Easy Ways to Ask "How Are You?" in Arabic

31 Jul, 2023 . 6 mins read

Want to learn Arabic?

Achieve incredible

results with our platform

24 Jul, 2023 . 5 mins read

24 Jul, 2023 . 4 mins read

More from AlifBee Blog

Uncategorized

Learn Arabic Faster: 10 Top Tips from Polyglots

Learning a new language can seem a difficult task especially when you start. Some languages are more difficult to acquire […]

6 Essential Practices in Eid Al-Fitr

Eid Al-Fitr Day First, let me start by wishing you a very happy Eid Al-Fitr. Second, let me tell you […]

Celebrate Eid Al-Fitr with 6 Arabic Phrases

We wish our dear readers, Arabic language learners, and the Muslim community a Happy Eid. Do you want to learn […]

Five Essential Occasions in Islam

Celebrated Occasions in Islam Five main occasions are celebrated by Muslims around the world every year. Each holds a unique […]

- Search Menu

- Browse content in Arts and Humanities

- Browse content in Archaeology

- Anglo-Saxon and Medieval Archaeology

- Archaeological Methodology and Techniques

- Archaeology by Region

- Archaeology of Religion

- Archaeology of Trade and Exchange

- Biblical Archaeology

- Contemporary and Public Archaeology

- Environmental Archaeology

- Historical Archaeology

- History and Theory of Archaeology

- Industrial Archaeology

- Landscape Archaeology

- Mortuary Archaeology

- Prehistoric Archaeology

- Underwater Archaeology

- Urban Archaeology

- Zooarchaeology

- Browse content in Architecture

- Architectural Structure and Design

- History of Architecture

- Residential and Domestic Buildings

- Theory of Architecture

- Browse content in Art

- Art Subjects and Themes

- History of Art

- Industrial and Commercial Art

- Theory of Art

- Biographical Studies

- Byzantine Studies

- Browse content in Classical Studies

- Classical History

- Classical Philosophy

- Classical Mythology

- Classical Literature

- Classical Reception

- Classical Art and Architecture

- Classical Oratory and Rhetoric

- Greek and Roman Epigraphy

- Greek and Roman Law

- Greek and Roman Papyrology

- Greek and Roman Archaeology

- Late Antiquity

- Religion in the Ancient World

- Digital Humanities

- Browse content in History

- Colonialism and Imperialism

- Diplomatic History

- Environmental History

- Genealogy, Heraldry, Names, and Honours

- Genocide and Ethnic Cleansing

- Historical Geography

- History by Period

- History of Emotions

- History of Agriculture

- History of Education

- History of Gender and Sexuality

- Industrial History

- Intellectual History

- International History

- Labour History

- Legal and Constitutional History

- Local and Family History

- Maritime History

- Military History

- National Liberation and Post-Colonialism

- Oral History

- Political History

- Public History

- Regional and National History

- Revolutions and Rebellions

- Slavery and Abolition of Slavery

- Social and Cultural History

- Theory, Methods, and Historiography

- Urban History

- World History

- Browse content in Language Teaching and Learning

- Language Learning (Specific Skills)

- Language Teaching Theory and Methods

- Browse content in Linguistics

- Applied Linguistics

- Cognitive Linguistics

- Computational Linguistics

- Forensic Linguistics

- Grammar, Syntax and Morphology

- Historical and Diachronic Linguistics

- History of English

- Language Acquisition

- Language Evolution

- Language Reference

- Language Variation

- Language Families

- Lexicography

- Linguistic Anthropology

- Linguistic Theories

- Linguistic Typology

- Phonetics and Phonology

- Psycholinguistics

- Sociolinguistics

- Translation and Interpretation

- Writing Systems

- Browse content in Literature

- Bibliography

- Children's Literature Studies

- Literary Studies (Asian)

- Literary Studies (European)

- Literary Studies (Eco-criticism)

- Literary Studies (Romanticism)

- Literary Studies (American)

- Literary Studies (Modernism)

- Literary Studies - World

- Literary Studies (1500 to 1800)

- Literary Studies (19th Century)

- Literary Studies (20th Century onwards)

- Literary Studies (African American Literature)

- Literary Studies (British and Irish)

- Literary Studies (Early and Medieval)

- Literary Studies (Fiction, Novelists, and Prose Writers)

- Literary Studies (Gender Studies)

- Literary Studies (Graphic Novels)

- Literary Studies (History of the Book)

- Literary Studies (Plays and Playwrights)

- Literary Studies (Poetry and Poets)

- Literary Studies (Postcolonial Literature)

- Literary Studies (Queer Studies)

- Literary Studies (Science Fiction)

- Literary Studies (Travel Literature)

- Literary Studies (War Literature)

- Literary Studies (Women's Writing)

- Literary Theory and Cultural Studies

- Mythology and Folklore

- Shakespeare Studies and Criticism

- Browse content in Media Studies

- Browse content in Music

- Applied Music

- Dance and Music

- Ethics in Music

- Ethnomusicology

- Gender and Sexuality in Music

- Medicine and Music

- Music Cultures

- Music and Religion

- Music and Media

- Music and Culture

- Music Education and Pedagogy

- Music Theory and Analysis

- Musical Scores, Lyrics, and Libretti

- Musical Structures, Styles, and Techniques

- Musicology and Music History

- Performance Practice and Studies

- Race and Ethnicity in Music

- Sound Studies

- Browse content in Performing Arts

- Browse content in Philosophy

- Aesthetics and Philosophy of Art

- Epistemology

- Feminist Philosophy

- History of Western Philosophy

- Metaphysics

- Moral Philosophy

- Non-Western Philosophy

- Philosophy of Science

- Philosophy of Language

- Philosophy of Mind

- Philosophy of Perception

- Philosophy of Action

- Philosophy of Law

- Philosophy of Religion

- Philosophy of Mathematics and Logic

- Practical Ethics

- Social and Political Philosophy

- Browse content in Religion

- Biblical Studies

- Christianity

- East Asian Religions

- History of Religion

- Judaism and Jewish Studies

- Qumran Studies

- Religion and Education

- Religion and Health

- Religion and Politics

- Religion and Science

- Religion and Law

- Religion and Art, Literature, and Music

- Religious Studies

- Browse content in Society and Culture

- Cookery, Food, and Drink

- Cultural Studies

- Customs and Traditions

- Ethical Issues and Debates

- Hobbies, Games, Arts and Crafts

- Lifestyle, Home, and Garden

- Natural world, Country Life, and Pets

- Popular Beliefs and Controversial Knowledge

- Sports and Outdoor Recreation

- Technology and Society

- Travel and Holiday

- Visual Culture

- Browse content in Law

- Arbitration

- Browse content in Company and Commercial Law

- Commercial Law

- Company Law

- Browse content in Comparative Law

- Systems of Law

- Competition Law

- Browse content in Constitutional and Administrative Law

- Government Powers

- Judicial Review

- Local Government Law

- Military and Defence Law

- Parliamentary and Legislative Practice

- Construction Law

- Contract Law

- Browse content in Criminal Law

- Criminal Procedure

- Criminal Evidence Law

- Sentencing and Punishment

- Employment and Labour Law

- Environment and Energy Law

- Browse content in Financial Law

- Banking Law

- Insolvency Law

- History of Law

- Human Rights and Immigration

- Intellectual Property Law

- Browse content in International Law

- Private International Law and Conflict of Laws

- Public International Law

- IT and Communications Law

- Jurisprudence and Philosophy of Law

- Law and Politics

- Law and Society

- Browse content in Legal System and Practice

- Courts and Procedure

- Legal Skills and Practice

- Primary Sources of Law

- Regulation of Legal Profession

- Medical and Healthcare Law