1986 Tour de France

73rd edition: july 4 - july 27, 1986, results, stages with running gc, map, video, photos and history.

1985 Tour | 1987 Tour | Tour de France Database | 1986 Tour Quick Facts | 1986 Tour de France Final GC | Stage results with running GC | The Story of the 1986 Tour de France by Bill & Carol McGann | The 1986 Tour by Owen Mulholland | Video

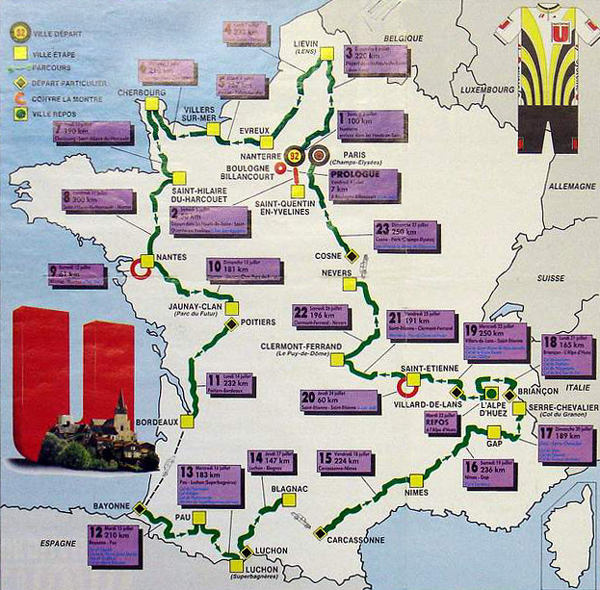

Map of the 1986 Tour de France route

Plato's Crito is available as an audiobook here .

1986 Tour de France quick facts:

210 riders started the 4,083 kilometer race, 132 finished.

The 23 stages were ridden at an average speed of 37.020 km/hr.

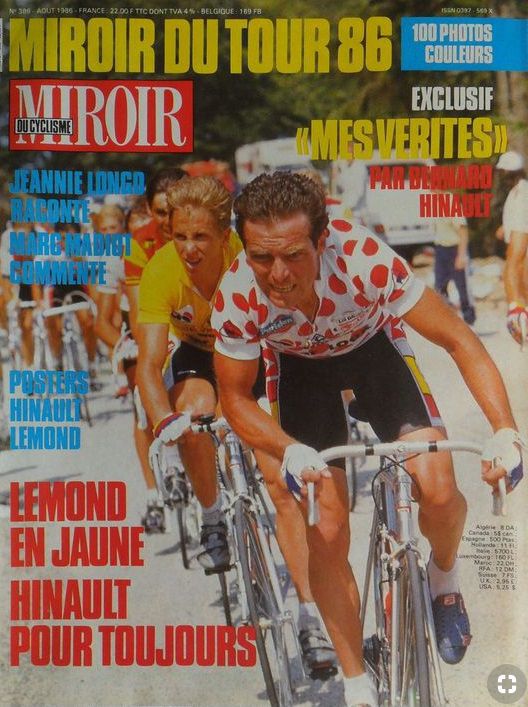

Greg LeMond's 1986 Tour de France victory was the first by an American and the first of three Tour wins by LeMond.

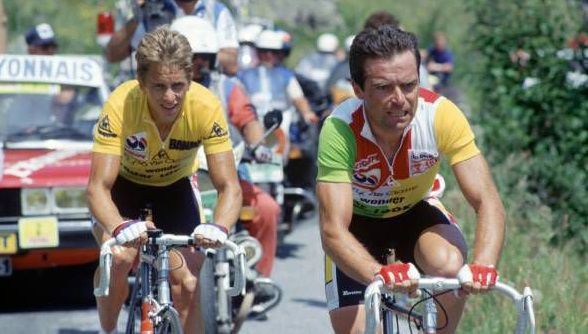

At the end of the 1985 Tour Bernard Hinault had promised to help LeMond win the Tour in 1986.

Hinault reneged on the promise and constantly attacked LeMond.

To this day Hinault insists he was helping LeMond win the Tour.

Complete Final 1986 Tour de France General Classification:

- Bernard Hinault (La Vie Claire) @ 3min 10sec

- Urs Zimmermann (Carrera) @ 10min 54sec

- Andrew Hampsten (La Vie Claire) @ 18min 44sec

- Claude Criquielion (Hitachi) @ 24min 36sec

- Ronan Pensec (Peugeot) @ 25min 59sec

- Niki Rutimann (La Vie Claire) @ 30min 52sec

- Alvaro Pino (ZOR) @ 33min

- Steven Rooks (PDM) @ 33min 22sec

- Yvon Madiot (Système U) @ 33min 27sec

- Samuel Cabrera (Reynolds) @ 35min 28sec

- Jean-François Bernard (La Vie Vlaire) @ 35min 45sec

- Pascal Simon (Peugeot) @ 37min 44sec

- Eduardo Chozas (Teka) @ 38min 48sec

- Reynel Montoya (Postobon) @ 45min 36sec

- Charly Mottet (Système U) @ 45min 58sec

- Thierry Claveyrolat (RMO) @ 46min 0sec

- Marino Lejaretta (Seat-Orbea) @ 49min 9sec

- Jean-Claude Bagot (Fagor) @ 51min 38sec

- Eric Caritoux (Fagor) @ 52min 39sec

- José Patrocinio Jiménez (Cafe de Colombia) @ 55min 42sec

- Luis Alberto Herrera (Cafe de Colombia) @ 56min 0sec

- Steve Bauer (La Vie Claire) @ 56min 2sec

- Joop Zoetemelk (Kwantum Hallen) @ 57min 4sec

- Jesus Blanco (Teka) @ 1hr 3min 16sec

- Jean-René Bernaudeau (Fagor) @ 1hr 3min 56sec

- Alfonso Florez (Cafe de Colombia) @ 1hr 5min 54sec

- Bernard Gavillet (Système U) @ 1hr 8min 17sec

- Peter Stevenhaagen (PDM) @ 1hr 10min 40sec

- Jokin Mujika (Seat-Orbea) @ 1hr 11min 1sec

- Anselmo Fuerte (Zor-BH) @ 1hr 12min 13sec

- Primoz Cerin (Malvor-Bottecchia) @ 1hr 14min 40sec

- José Anselmo Agudelo (Teka) @ 1hr 15min 13sec

- Dag Otto Lauritzen (Peugeot) @ 1hr 15min 47sec

- Robert Forest (Peugeot) @ 1hr 16min 19sec

- Pello Ruiz (Seat-Orbea) @ 1hr 16min 22sec

- Eddy Schepers (Carrera) @ 1hr 18min 20sec

- Federico Echave (Teka) @ 1hr 18min 53sec

- Phil Anderson (Panasonic) @ 1hr 19min 41sec

- Jesús Rodríguez (Zor-BH) @ 1hr 20min 9sec

- Silvano Contini (Gis Gelati) @ 1hr 22min 18sec

- Martin Alonso Ramirez (Fagor) @ 1hr 22min 26sec

- Hendrik Devos (Hitachi-Marc) @ 1hr 24min 43sec

- Charly Berard (La Vie Claire) @ 1hr 29min 2sec

- Dominique Garde (KAS) @ 1hr 29min 11sec

- Martin Earley (Fagor) @ 1hr 30min 30sec

- Gilles Mas (RMO) @ 1hr 31min 56sec

- Stephen Roche (Carrera) @ 1hr 32min 30sec

- Erich Mächler (Carrera) @ 1hr 32min 45sec

- Heriberto Uran (Postobon) @ 1hr 36min 35sec

- Jan Nevens (Joker) @ 1hr 37min 15sec

- Johan van der Velde (Panasonic) @ 1hr 37min 55sec

- Carlos Hernández (Reynolds) @ 1hr 38min 13sec

- Guy Nulens (Panasonic) @ 1hr 39min 8sec

- Carlos Jamrillo (Postobon) @ 1hr 39min 48sec

- Jean-Claude Leclercq (KAS) @ 1hr 40min 43sec

- Jean-Claude Garde (KAS) @ 1hr 40min 57sec

- Jean-Philippe Vandenbrande (Hitachi-Marc) @ 1hr 41min 23sec

- Juan Carlos Rozas (Zor-BH) @ qhr 41min 51sec

- Enrique Aja (Teka) @ 1hr 42min 32sec

- Gerard Veldscholten (PDM) @ 1hr 42min 57sec

- Bernard Vallet (RMO) @ 1hr 43min 12sec

- Bob Roll (7-Eleven) @ 1hr 43min 26sec

- Dirk De Wolf (Hitachi-Marc) @ 1hr 44min 17sec

- Twan Poels (Kwantum Hallen) @ 1hr 44min 17sec

- Ennio Vanotti (Gis Gelati) @ 1hr 45min 20sec

- Paul Haghedooren (Joker) @ 1hr 47min 59sec

- François Lemarchand (Fagor) @ 1hr 49min 5sec

- Ludo Peeters (Kwantum Hallen) @ 1hr 49min 11sec

- Nico Emonds (Kwantum Hallen) @ 1hr 49min 19sec

- Manuel Cardenas (Teka) @ 1hr 50min 11sec

- Guido Van Calster (Zor-BH) @ 1hr 50min 42sec

- Bruno Leali (Carrera) @ 1hr 51min 49sec

- Beat Breu (Carrera) @ 1hr 51min 54sec

- Iñaki Gaston (KAS) @ 1hr 52min 35sec

- Dominique Arnaud (Reynolds) @ 1hr 53min 54sec

- Jørgen V. Pedersen (Carrera) @ 1hr 54min 32sec

- Jos Haex (Hitachi-Marc) @ 1hr 54min 38sec

- Julian Gorospe (Reynolds) @ 1hr 56min 11sec

- Jeff Pierce (7-Eleven) @ 1hr 56min 57sec

- Maarten Ducrot (Kwantum Hallen) @ 1hr 56min 2sec

- Acácio da Silva (Malvor-Bottecchia) @ 1hr 58min 5sec

- Nestor Oswaldo Mora (Postobon) @ 1hr 58 26sec

- Gerrie Knetemann (PDM) @ 1hr 58min 28sec

- Dominique Gaigne (Système U) @ 1hr 59min 27sec

- Marco Antonio Leon (Cafe de Colombia) @ 2hr 0min 49sec

- Vicente-Juan Ridaura (Seat-Orbea) @ 2hr 0min 59sec

- Christophe Lavainne (Système U) @ 2hr 1min 0sec

- Eric van Lancker (Panasonic) @ 2hr 1min 53sec

- Jan van Wijk (PDM) @ 2hr 2min 35sec

- Alessandro Ponzzi (Gis Gelati) @ 2hr 3min 39sec

- Guido Bontempi (Carrera) @ 2hr 3min 39sec

- Régis Simon (RMO) @ 2hr 5min 6sec

- Francisco-José Antequera (Zor-BH) @ 2hr 5min 8sec

- Alain Vigneron (La Vie Claire) @ 2hr 5min 8sec

- Ron Kiefel (7-Eleven) @ 2hr 6min 38sec

- Philippe Leleu (La Vie Claire) @ 2hr 7min 3sec

- Eric Boyer (Systéme U) @ 2hr 7min 27sec

- Jörg Müller (KAS) @ 2hr 7min 46sec

- Frédéric Vichot (KAS) @ 2hr 8min 15sec

- Gerrit Solleveld (Kwantum Hallen) @ 2hr 9min 0sec

- Willem van Eynde (Joker) @ 2hr 10min 46sec

- Luc Roosen (Kwantum Hallen) @ 2hr 10min 46sec

- Rudy Rogiers (Hitachi-Marc) @ 2hr 11min 9sec

- Jan Wynants (Hitachi-Marc) @ 2hr 11min 14sec

- Israel Corredor (Postobon) @ 2hr 12min 4sec

- Frédéric Brun (Peugeot) @ 2hr 13min 11sec

- Thierry Marie (Système U) @ 2hr 13min 24sec

- Francesco Rossignoli (Carrera) @ 2hr 13min 56sec

- Adrie van der Poel (Kwantum Hallen) @ 2hr 14min 20sec

- Eric Louvel (Peugeot) @ 2hr 14min 41sec

- Sean Yates (Peugeot) @ 2hr 15min 20sec

- Michael Dernies (Joker) @ 2hr 15min 29sec

- Raúl Alcalá (&-Eleven) @ 2hr 15min 53sec

- Jaime Vilamajo (Seat-Orbea) @ 2hr 16min 41sec

- Frank Hoste (Fagor) @ 2hr 17min 6sec

- Jesús Hernández (Reynolds) @ 2hr 17min 26sec

- André Chappuis (RMO) @ 2hr 17min 36sec

- Jean-Luc Vandenbroucke (KAS) @ 2hr 17min 58sec

- Alex Stieda (&-Eleven) @ 2hr 19min 47sec

- José Luis Laguia (Reynolds) @ 2hr 19min 49sec

- Rudy Dhaenens (Hitachi-Marc) @ 2hr 19min 58sec

- Marc Gomez (Reynolds) @ 2hr 21min 13sec

- Alain Bondue (Systéme U) @ 2hr 22min 3sec

- Eric Vanderaerden (Panasonic) @ 2hr 22min 30sec

- Antonio Esparza (Seat-Orbea) @ 2hr 22min 45sec

- Guido Winterberg (La Vie Claire) @ 2hr 27min 26sec

- Pierangelo Bincoletto (Malvor-Bottecchia) @ 2hr 27min 28sec

- Jozef Lieckens (Joker) @ 2hr 29min 21sec

- Francis Castaing (RMO) @ 2hr 41min 56sec

- Paul kimmage (RMO) @ 2hr 44min 6sec

- Ennio Salvador (Gis Gelati) @ 2hr 55min 51sec

Climbers' Competition:

- Luis Herrera (Cafe de Colombia): 270

- Greg LeMond (La Vie Claire): 265

- Urs Zimmermann (Carrera): 191

- Eduardo Chozas (Teka): 172

- Samuel Cabrera (Reynolds): 162

- Ronan Pensec (Peugeot): 139

- Andrew Hampsten (La Vie Claire): 133

- Claude Criquielion (Hitachi-Marc): 123

- Jean-François Bernard (La Vie Claire)

Points Competition:

- Jozef Lieckens (Joker): 232

- Bernard Hinault (La Vie Claire): 210

- Greg LeMond (La Vie Claire): 210

- Guido Bontempi (Carrera): 166

Team Classification :

- La Vie Claire: 331hr 35min 48sec

- Peugeot @ 1hr 51min 50sec

- Système U @ 2hr 0min 50sec

- PDM @ 2hr 23min 50sec

- Carrera @ 2hr 26min 36sec

- Fagor @ 2hr 28min 52sec

- Teka @ 2hr 43min 36sec

- Zor-BH @ 2hr 43min 36sec

- Cafe de Colombia @ 2hr 55min 45sec

Team Points:

- Panasonic: 1,523 points

- La Vie Claire: 1,674

Best New Rider:

- Andrew Hampsten (La Vie Claire): 110hr 54min 3sec

- Ronan Pensec (Peugeot) @ 7min 15sec

- Jean-François Bernard @ 17min 1sec

- Jesus Blanco (Teka) @ 44min 32sec

- Peter Stevenhaagen (PDM) @ 51min 56sec

Content continues below the ads

Individual stage results with principal climbs and running GC

Prologue: Friday, July 4, Boulogne-Billancourt, 4.6 km. GC and stage times are the same.

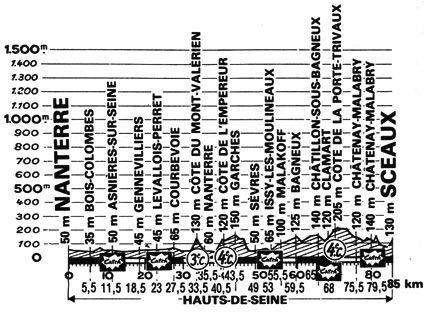

Stage 1: Saturday, July 5, Nanterre - Sceaux, 85 km

GC after Stage 1:

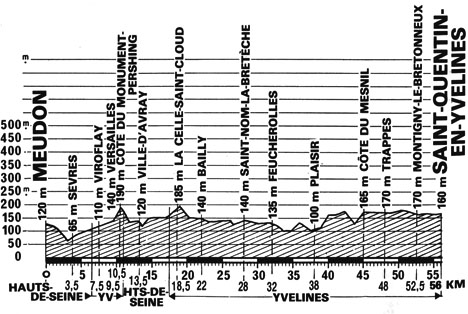

Stage 2: Saturday, July 5, Meudon - St. Quentin en Yveline 56 km Team Time Trial

GC after Stage 2:

Stage 3: Sunday, July 6, Levallois Perret - Liévin, 214 km

GC after Stage 3:

S tage 4: Monday, July 7, Liévin - Evreux, 243 km

GC after Stage 4:

Stage 5: Tuesday, July 8, Evreux - Villers sur Mer, 124.5 km

GC after Stage 5:

Stage 6: Wednesday, July 9, Villers sur Mer - Cherbourg, 200 km

GC after Stage 6:

Stage 7: Thursday, July 7, Cherbourg - St. Hilaire du Harcouët, 201 klm

GC after Stage 7:

Stage 8: Friday, July 11, St Hilaire du Harcouët - Nantes, 204 km

GC after Stage 8:

Stage 9: Saturday, July 12, Nantes 61.5 km Individual Time Trial

GC after Stage 9:

Stage 10: Sunday, July 13, Nantes - Futuroscope, 183 km

GC after Stage 10:

Stage 11: Monday, July 14, Poitiers - Bordeaux, 258.3 km

GC after Stage 11:

Stage 12: Tuesday, July 15, Bayonne - Pau, 217.5 km

GC after Stage 12:

Stage 13: Wednesday, July 16, Pau-Superbagnères 186 km

GC after Stage 13:

Stage 14: Thursday, July 17, Luchon - Blagnac, 154 km

GC after Stage 14:

Stage 15: Friday, July 18, Carcassonne - Nîmes, 225.5 km

GC after Stage 15:

Stage 16: Saturday, July 19, Nîmes - Gap, 246.5 km

GC after Stage 16:

Stage 17: Sunday, July 20, Gap - Serre Chevalier, 190 km

GC after Stage 17:

Stage 18: Monday, July 21, Briançon - L'Alpe d'Huez , 162.5 km

GC after stage 18:

Stage 19: Wednesday, July 23, Villard de Lans - St. Etienne, 179.5 km

GC after Stage 19:

Stage 20: Thursday, July 24, St. Etienne 58 km Individual Time Trial

GC after Stage 20:

Stage 21: Friday, July 25, St. Etienne - Puy de Dôme, 190 km

GC after Stage 21:

Stage 22: Saturday, July 26, Clermont Ferrand - Nevers, 194 km

GC after Stage 22:

23rd and Final Stage : Sunday, July 27, Cosne sur Loire - Paris (Champs Elysées) 255 km

Complete Final GC after Stage 23

The Story of the 1986 Tour de France

This excerpt is from "The Story of the Tour de France", Volume 2 If you enjoy it we hope you will consider purchasing the book, either print, eBook or audiobook. The Amazon link here will make the purchase easy.

Hinault had said to LeMond, "In '86 the Tour will be for you. I'll be there to help you." So easy to say in the heat of a moment when a teammate had made the sacrifice of a lifetime to let him win the 1985 Tour. Now, would Hinault have the character to fulfill his promise when he can taste immortality with six Tour wins?

This year saw not only the entry of American Greg LeMond with his ace climbing friend Andy Hampsten and Canadian Steve Bauer but also the entry of the first American team. 7-Eleven-Hoonved was entered with Bob Roll, 1984 Olympic gold medalist Alexei Grewal, Chris Carmichael, Eric Heiden, Alex Stieda, Jeff Pierce, Raul Alcala, Davis Phinney, Doug Shapiro (who had ridden on Joop Zoetemelk's Kwantum-Decosol Tour team in 1985) and Ron Kieffel. After the riders on La Vie Claire, they were the cream of the North American crop. I'll spoil one bit of the story right here. Bob Roll, who does analysis of bike racing on the Versus television network, was the highest placed 7-Eleven rider in Paris, despite getting sick mid-way though the 1986 Tour. Bob Roll was a very good rider.

If the politics and complicated jockeying amidst the tension of the La Vie Claire intra-team rivalry were tough in 1985, 1986 was even more difficult.

LeMond's spring had been good, but not spectacular:

LeMond's La Vie Claire teammate Andy Hampsten established his bona fides as a racer of the first rank when he won the Tour of Switzerland only a few short weeks before the start of the Tour. Hinault used that win as fodder for his psychological war against LeMond when he announced that Hampsten's Swiss victory made Hampsten, not LeMond, his real heir. How charming.

Hinault's spring was rather quiet with no top placings in important races.

Laurent Fignon, riding the colors of his team's new sponsor Systeme U, was working on his comeback after surgery on his Achilles tendon. He must have found some rather good form because he won the Flèche Wallonne in the spring.

Thierry Marie began the first of his 3 Prologue victories at the kickoff of the 1986 Tour. Hinault was third at 2 seconds, LeMond and Fignon were seventh and eighth at 4 seconds.

Stage 1, a short 85-kilometer race run in the outskirts of Paris saw 7-Eleven rider Alex Stieda take off at the 40-kilometer mark. He was eventually joined by 5 other riders, but not until Stieda had collected the intermediate sprint bonuses. The group of 6 managed to stay away from the charging field by only meters when they crossed the line. With the time bonuses Stieda had collected on his early solo effort, he was now the shock owner of the Yellow Jersey.

That same Saturday afternoon the teams lined up for a 56-kilometer team time trial. The 7-Eleven team was game to try to keep the Yellow Jersey but its efforts came apart when Eric Heiden crashed. Several other 7-Eleven riders scraped the curb to avoid following Heiden to the ground. That weakened the casings of their tires, causing several flat tires. Stieda, exhausted from his morning effort, ran out of gas. Carmichael and Pierce had to drop back and bring Stieda home making sure they got him there in time to avoid having him eliminated by missing the time cutoff. Stieda made it to the finish in time, but his tenure in Yellow was over.

Fignon's Systeme U squad won the stage. La Vie Claire had a bad day, losing almost 2 minutes. Thierry Marie, being a Systeme U rider, was back in Yellow with his teammates occupying the top 7 places in the General Classification.

Stage 3, in the northern roads of France, ended near the Belgian border. And there the freshman 7-Eleven team had another major success. Davis Phinney won the sprint by inches even after having been in a break for a lot of that day. As far as the real General Classification contenders were concerned, this was just another day to stay out of trouble.

It stayed that way until stage 9, a 61.5-kilometer individual time trial at Nantes. Now the Tour de France started in earnest. The stage results:

LeMond's performance was far better than his time showed. He flatted and it is estimated he lost almost a minute. It was clear that Fignon hadn't found his 1985 form yet.

General Classification:

Stage 12 was the first day in the Pyrenees with four highly rated climbs. The final climb was the first category Col de Marie-Blanque, followed by 45 kilometers of descent and flat before the finish at Pau.

The first major climb was the first category Burdincurutcheta at kilometer 80. Several groups of riders detached themselves. Notably, Hinault with Luis Herrera and Claude Criquielion were moving up from the second group to the leaders. Over the second climb, the Bargargui, Eduardo Chozas broke away on the descent. Hinault with teammates LeMond, Hampsten and Jean-François Bernard along with several other riders gave chase. After Chozas was caught, Hinault and Bernard attacked and got away. Pedro Delgado bridged up to them. They eventually spit out Chozas as the now 3 riders worked hard to put real distance on the racers behind them. LeMond was stuck. He could not chase his 2 teammates (Hinault and Bernard) up the road. Hinault and Delgado tore up the road, gaining scads of time on him as LeMond sat in the chasing group. Finally LeMond was able to extricate himself, taking along only Herrera. Hinault let Delgado have the stage, he had enough booty when LeMond came in 4 minutes, 37 seconds later. This was helping LeMond win the Tour? Hinault knew that if he were on the attack and in the lead, he would neutralize LeMond.

The General Classification at this point:

The stage was so tough and the pace so hot, 17 riders abandoned. The next morning 2 more quit, including Fignon.

Stage 13 only got harder with 4 major climbs: the Tourmalet, the Aspin, the Peyresourde and the final Hors Category climb to Superbagnères. On the descent of the Tourmalet Hinault attacked and got away. At the bottom he had a lead of 1 minute, 43 seconds. Again LeMond was stuck, unable to race. He had to let the others do the chasing. By the bottom of the Aspin, the gap between Hinault and about 30 chasers was 2 minutes, 54 seconds.

On the Peyresourde, Hinault started to show signs of fatigue. A much reduced chase group of Zimmermann, LeMond, Hampsten, Millar and Herrera had cut the lead to 25 seconds. On the descent of the Peyresourde, Hinault was caught.

The final climb to the ski station of Superbagnères is 16 kilometers of Hors Category work. Hinault rode with the group that had caught him, totaling 9 riders. On the climb he attacked again and got away. Now it was just Hampsten, LeMond, Zimmermann, Millar and Herrera chasing and with 10 kilometers to go, Hinault was caught.

With 7 kilometers to go Hampsten attacked and took LeMond with him. Hampsten pounded up the mountain for all he was worth, while LeMond still hesitated, sitting on Hampsten's wheel. Then, as Hampsten could no longer keep up the infernal pace, he yelled at LeMond to take off and win the stage. LeMond finally shed his hesitancy and raced up the mountain for a great stage win as Hinault was being passed by rider after rider further down the mountain. LeMond's gain on Hinault that day was 4 minutes, 39 seconds, almost the same amount of time he lost the day before. Hinault was in Yellow but LeMond had shown that he had the ability to win the Tour, sitting only 40 seconds behind the fading leader.

The stages after the Pyrenees that went across southern France heading towards the Alps changed nothing in the General Classification.

Stage 17, the first Alpine stage, was the scene of the denouement of this story, with crossings of the Col de Vars, Col d'Izoard and a hilltop finish at the top of the Col de Granon. The first climb was rated first category and the final 2 were Hors Category.

Various groups attacked and riders were scattered all over the mountains. The story that matters to us is on the descent of the Izoard. Zimmermann, sitting in third place in the General Classification, got a gap. LeMond, acting as an attentive domestique , latched onto his wheel. Hinault was about 90 seconds behind them. On the Granon, LeMond, ever dutiful, sat on Zimmermann as the Swiss rider poured on the gas. Hinault, now aware of the situation attacked hard but Zimmermann with LeMond in tow was gaining time with every pedal stroke. Eduardo Chozas, never in contention for the overall, had been off the front and won the stage, but that didn't matter to LeMond. He was in Yellow.

The next day was no easier with the Galibier and its little brother the Télégraphe, followed by the Croix de Fer and a hilltop finish at L'Alpe d'Huez.

On the descent of the Galibier Hinault attacked with Bauer on his wheel. LeMond, Zimmermann and Pello Ruiz-Cabestany caught him as they continued the descent. On the short ascent up the Télégraphe Hinault made another attempt to get away, this time making it stick for 15 kilometers. LeMond, Bauer and Ruiz-Cabestany managed to hook up with Hinault without bringing Zimmermann, who was sitting ahead of Hinault in the General Classification. The quartet put down their collective heads and started to work. The pace was too hot for Bauer and Ruiz-Cabestany and on the first category Croix de Fer it was just Hinault and LeMond.

This was the day Zimmermann saw his chances for winning the Tour disappear. 7 kilometers from the top of the Croix de Fer Zimmermann was in a group that included Hampsten, Pascal Simon and Joop Zoetemelk. They were 3 minutes, 10 seconds behind LeMond and Hinault. Zimmerman dug deep and attacked, trying to get up to the duo. He closed the gap a little, being 2 minutes, 50 seconds behind at the top.

On the descent Hinault and LeMond flew. Both were superb bike handlers. Years ago former 7-Eleven rider Jeff Pierce and I were talking about this stage and I remember the one thing Pierce wanted to make sure that I understood: LeMond could descend and descend extremely fast. At the beginning of the Alpe, in Bourg d'Oisans, LeMond and Hinault were 4 minutes, 50 seconds ahead of Zimmermann. LeMond and Hinault continued to throw high heat on the mountain until Hinault conceded and asked LeMond to back off, his words being, "Stay with me". Generously LeMond joined hands with his tormentor and pushed Hinault ahead a bit so that he could take the stage victory. LeMond had survived another test from his little French helper. Hinault had buried Zimmermann and had claimed second place in the General Classification. The gift of the stage win was nice of LeMond, but I'd have completely dropped Hinault and left him for dead as far down the mountain as possible to make sure he couldn't try something later. Hinault never gave up, and would take any advantage that opportunity or his own talents presented. To prove my point, in a post-stage interview Hinault said, "The race isn't over." You can imagine LeMond's dismay.

The General Classification after L'Alpe d'Huez:

Owen Mulholland, who was the first American journalist to ride in the Tour's press caravan, sent me these comments regarding stage 17: "As you note, Hinault attacked on the short 2-kilometer climb out of Valloire that serves as the southern slope of the Col de Télégraphe. I'm not sure why Greg was caught napping so often by these surprise attacks. It's impossible to imagine, say, Merckx, missing such moves time after time. Anyway, once again Hinault was gone and Greg was stuck. However the descent of the Télégraphe is extremely sinuous and was made for Greg's fabulous descending skills. I remember his talking (laughing) to Hinault later about how he'd gotten rid of Zimmermann on that descent. It seems Zimmermann skidded across a corner trying to hang onto Greg's wheel and that's the last anyone up front ever saw of the poor Swiss that day! I believe (but am not absolutely certain) Bauer was already away, but in any event he was in the front, so when Greg and Bernard hooked up with him and a few others in the flat valley of the Maurienne, Steve lowered his head and motored to the foot of the Croix de Fer. Poor Zimmermann never stood a chance."

Stage 20 was the next real test, a 58-kilometer individual time trial at St. Etienne. LeMond's normal luck continued when he crashed at kilometer 37. He remounted and found his brake rubbing the rim. He had to change bikes, costing him still more time. Hinault rode his time trial perfectly and won the stage, beating the crash-starred LeMond by 25 seconds. Zimmermann was unable to present any challenge and finished almost 3 minutes behind Hinault. While the race tightened a little, there was no real change in the overall standings.

There was 1 last day in the mountains of this really tough Tour. Stage 21 went into the Massif Central with several highly rated climbs culminating in a hilltop finish at the famous Puy de Dôme. The contenders had more or less accepted their positions while riders seeking individual glory in the closing days of the race sought their day in the sun. The only real action that could affect things was on the final ascent. LeMond pulled away from Zimmermann who distanced himself slightly from Hinault. LeMond was now 3 minutes, 10 seconds ahead of Hinault and had only 2 more stages to negotiate.

LeMond's luck stuck to him like a bad rumor. Shortly before entering Paris on the final day's stage, LeMond crashed badly enough to need a new bike. Hinault and his La Vie Claire teammates waited for him and motored him safely back into the field. Hinault, ever the tough competitor joined the final field sprint on the Champs Elysées and nailed fourth place. Big Guido Bontempi was the winner.

Paul Kimmage, who rode for the RMO squad, wrote about the final stage in this Tour in his book Rough Ride . Many of the riders were on their last legs by the time the final day in Paris arrived. In 1986, of the 210 riders who started, only 131 finished. The veterans told Kimmage about the blistering speeds of the final kilometers on the Champs Elysées. Fearful of getting dropped while the whole world watched, more than a few took amphetamines to get them over the Tour's final cobblestones. Kimmage asked the others if they weren't afraid of getting caught in the dope controls. No, he was told, only the winner and top finishers are tested after the final stage. They knew they were free to stick the needles in their arms.

The race was finally over and Greg LeMond had fulfilled his promise. When he was 17 he had written down his goal of winning the Tour de France.

Here's the final 1986 Tour de France General Classification:

Hinault won the Polka-Dot climber's jersey and Hampsten earned the white Young Rider's jersey. In addition, La Vie Claire won the team General Classification. This was a dominating performance in a Tour in which the only real question was which of the La Vie Claire riders would actually win.

Over the years the debate about this Tour has grown ever more heated.

Hinault has defended his actions repeatedly, saying that he was really helping LeMond by challenging him and forcing him to earn the Tour. Hinault's answer to his critics, "I'd given my word to Greg LeMond that I'd help him win and that's what I did. A promise is a promise. I tried to wear out rivals to help him but I never attacked him personally…It wasn't my fault that he didn't understand this. When I think of some of the things he has said since the race ended, I wonder whether I was right not to attack him…I've worked for colleagues all my life without having the problems I had with Greg LeMond."

Here's Owen Mulholland's view from his Uphill Battle , discussing Hinault's repeated attacks in the Pyrenees:

"[Hinault] once told me he liked to 'play' with cycling, and doing something this outrageous two days in a row may have been his idea of play. No one will ever know because when he explained himself, Hinault played with words. And when credibility disappears so does reliability. Was this a gamble to win in a super-dominant manner? Was he trying to tire out the opposition so LeMond could go easily into the lead? Was this a bold gesture for the hell of it, a 'playful' gesture? Who can tell because Hinault's actions could be interpreted in myriad ways, and his words, intentionally deceptive, meant nothing. On such a 'solid' basis LeMond had to make decisions."

Of course, Hinault reneged on his promise. His words, that he was trying to toughen LeMond or get him to earn his Tour, are obvious nonsense. Hinault should be as ashamed of uttering such silliness as he should be of failing to honor his promise in a clear-cut, transparent way. Life really isn't all that complicated.

Video of the 1986 Tour de France. A couple of people have posted the CBS coverage of the Tour on YouTube. This one, part 1 of 10, is pretty clean

© McGann Publishing

- Race Previews

- Race Reports

- Race Photos

- Tips & Reviews

Fem van Empel To Start 2024 Road Season At Dwars Door Vlaanderen After Missing Gent-Wevelgem

Mastering long-distance cycling: endurance training strategies, tips and common mistakes, riders to look out for at dwars door vlaanderen men in 2024, lorena wiebes secures hard-fought victory at gent-wevelgem women’s race, mads pedersen edges out mathieu van der poel in epic gent-wevelgem duel.

Email: [email protected]

Puy de Dôme: the climb that punched Merckx from his throne

Mathew Mitchell

- Published on July 5, 2023

- in Men's Cycling

The Puy de Dôme has always been more than just a climb in the Tour de France. Over the years, this volcanic peak in the Massif Central of France has been a battleground for some of the most legendary cyclists in history, the location of iconic moments, dramatic wins, and heartbreaking losses. From its first inclusion in 1952 until its last appearance in 1988, Puy de Dôme has been the silent observer of numerous tales that have shaped the mythos of the Tour de France.

Table of Contents

The History of Puy de Dôme in the Tour de France

The inclusion of the Puy de Dôme in the Tour de France began with an unforgettable climb in 1952. The legendary Italian cyclist, Fausto Coppi, took the lead, breaking away 6 kilometres from the finish line to claim the first-ever victory atop the Puy de Dôme. His dominant performance cemented his legacy and marked the beginning of the climb’s legendary status.

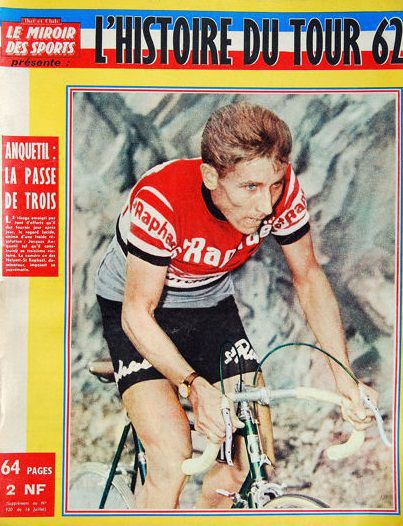

The Puy de Dôme’s steep and twisting slopes have been the scene of many epic battles. In 1964, the mountain was witness to the historic duel between two titans of French cycling: Jacques Anquetil and Raymond Poulidor. It was an arm-wrestling match on two wheels, with Poulidor attacking on the lower slopes and Anquetil clinging on desperately. Poulidor triumphed that day on the Puy de Dôme, but Anquetil ultimately won the war, taking his fifth Tour title.

1975: Merckx gets punched by a spectator

In 1975, Eddy Merckx , often hailed as the greatest cyclist of all time, was on his way to possibly securing his sixth Tour de France victory, which would have broken the record he then shared with Jacques Anquetil. As the reigning champion, all eyes were on him when the peloton reached the base of the Puy de Dôme.

The infamous incident occurred on the climb of the Puy de Dôme during stage 14. Merckx, wearing the leader’s yellow jersey, was making his way through the throng of spectators lining the narrow roads when an individual emerged from the crowd and punched him in the abdomen. The shock and the pain caused him to falter, slowing him down significantly.

What should have been another triumph for Merckx turned into a nightmare. He struggled to regain his rhythm after the assault, and the ensuing physical strain took its toll. Despite his best efforts, Merckx was unable to make up for the lost time and energy. The attack undeniably affected the remainder of his race.

It was Frenchman Bernard Thévenet who capitalized on Merckx’s misfortune. Sensing an opportunity, he powered ahead to claim the stage victory and, eventually, his first Tour de France win. The shocking incident on the Puy de Dôme did not just mark a stage win or a Tour victory. It symbolized the end of Merckx’s reign over the Tour de France and the beginning of a new era.

Despite this dramatic setback, Merckx showed incredible resilience, finishing the Tour in second place overall. His performance post-incident spoke volumes of his character and his place among the pantheon of cycling greats. However, the 1975 Tour de France will forever be remembered for the shocking incident on the Puy de Dôme, a poignant example of the unpredictability and high drama of the world’s greatest cycling race.

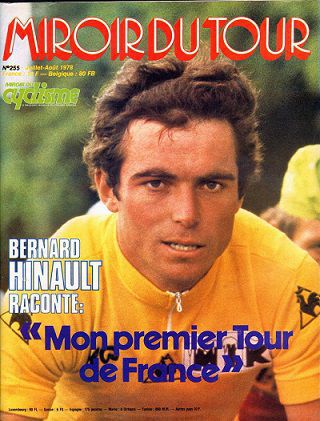

1978: Hinault in trouble

The 1978 Tour de France was another notable chapter in the history of the Puy de Dôme. This year, the legendary climb served as the setting along the way for Bernard Hinault’s impressive overall victory.

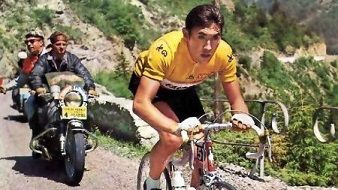

Bernard Hinault , also known as “Le Blaireau” (The Badger), was in his prime during the late 1970s. Known for his fierce determination and aggressive style, Hinault had earned a reputation as a formidable contender. He would secure his first Tour de France victory in 1978 but was sitting in 2nd place as the riders reached the Puy de Dôme on Stage 14.

The Puy de Dôme was the final climb of a brutal 32km ITT stage that day. A stage that ended with an individual ascent of the Puy de Dôme with all of the eyes of the fans on the contenders.

Despite going on to win that year’s Tour de France, Hinault was put in serious trouble that day by Joop Zoetemelk who would win the stage. 3rd in GC before the start of the stage, he was 53″ behind Inault in 2nd, who was 65″ behind the yellow jersey Joseph Bruyère. Hinault and Zoetemelk would effectively swap positions and time gaps as Hinault could only finish 4th on the Puy de Dôme a full 1’40” behind Zoetemelk and 45″ behind Bruyère.

Bernard Hinault’s dogged determination for the rest of that Tour de France to claw back time is what gifted it legendary status. A stage win the next day into Saint-Étienne was followed by a storming rider on Alpe d’Huez that saw Zoetemelk take over the yellow jersey but with a lead of only 14″ on Hinault. The TT on Stage 20 saw Hinault storm past Zoetemelk and effectively secure his first Tour de France win.

1986: The Badger and the L’Americain

The 1986 edition of the Tour de France remains one of the most dramatic and controversial in the history of the race, with the iconic Puy de Dôme climb playing a significant role. The narrative of this edition was centred around the intense rivalry and power struggle within the La Vie Claire team, between the defending champion, Bernard Hinault, and his teammate, the rising American star, Greg LeMond .

Throughout the 1986 Tour, Hinault and LeMond were engaged in a fierce internal duel. Despite Hinault’s public promise to support LeMond after the American had helped him secure his victory in the previous year’s Tour, Hinault appeared to have different plans as the race unfolded.

The tension within the team reached a climax during the mountainous Stage 21, which culminated with the climb of the Puy de Dôme. Greg Lemond finished 17th as the break other climbers not close in the GC finished ahead but importantly the American finished 52″ ahead of teammate Hinault and finally put paid to the Frenchman’s hopes of another Tour win. With no major tests to come, the now extended gap of 3’10” was too much to close.

Erich Maechler of Carrera Jeans-Vagabond was the rider who actually won on the Puy de Dôme in the 1986 Tour de France, finishing 34″ ahead of Ludo Peeters.

The 1986 Tour de France concluded with Greg LeMond in the yellow jersey, the first American to ever win the Tour. His victory, however, was marred by the controversy and the intra-team rivalry with Hinault. The dramatic battle on the Puy de Dôme became a symbol of this tension and remains one of the most significant moments of LeMond’s career.

In retrospect, the 1986 edition of the Tour de France signalled a shift in power, with the torch being passed from the dominant Hinault to a new generation of riders represented by LeMond. The Puy de Dôme climb once again played a pivotal role in shaping the narrative of the race and the evolution of professional cycling.

The end of an era

After 1988, the Puy de Dôme disappeared from the Tour de France. The reason lies in logistical issues and the mounting concerns over the safety of the riders and spectators alike. The narrow, winding roads leading to the peak were simply not built to accommodate the modern, increasingly large Tour de France caravan.

In 2006, local authorities built a train line, the Panoramique des Dômes , to ferry tourists up the mountain, and later on would prohibit cycling on the ascent to protect the natural environment and ensure the safety of visitors. Thus, cycling up the Puy de Dôme is now a forbidden pleasure, reserved for the few events each year where it is allowed.

The legacy of Puy de Dôme

The 2023 Tour de France sees the race return to the Puy de Dôme, which retains its iconic status in the world of cycling. The mountain’s steep, serpentine roads and panoramic views at the summit capture the romantic essence of the sport, where man, machine, and nature meet in a dramatic contest of physical and mental endurance. It’s a symbol, a witness to the evolution of the Tour de France, and a shrine to the legends of the sport. Its slopes tell the stories of heroes and villains, triumphs and losses, battles and alliances, all woven into the rich tapestry of the Tour’s history.

Its absence from the Tour hasn’t stopped the Puy de Dôme from being alive in the heart of the Tour de France and cycling enthusiasts around the world. Despite its long 35 years of absence from the race, the Puy de Dôme remains an emblem of the Tour de France, symbolising the drama, the passion, and the enduring allure of the world’s most famous cycling race.

Related Posts

Tour de France 1986 : classement de l'étape St Etienne - Puy de Dôme (189kms)

Les étapes du Tour de France 1986

© Miroir du Cyclisme

73 ème Tour de France

4 au 27 juillet 1986.

clm : Contre-la-montre clme : Contre-la-montre par équipes

© ledicodutour.com

Tour de France 1986

© Le Parisien L'Equipe

© Photo : Courtesy Patricio Saldivia Saldivia Noack www.dewielersite.net

Le Tour de France 1986

Le tour de france depuis 1947.

Retrouvez les archives vidéo du Tour de France avec l'INA (Institut national de l'Audiovisuel)

Vous devez installer Adobe Flash Player pour lire les vidéos

Tour de France 1986 Etape 9

Contre-la-montre à Nantes

Résumé - 12/07/1986 - 02'47"

9 ème étape du Tour de France 1986, un contre-la-montre individuel de 61 km à Nantes. Arrivée de Bernard HINAULT, qui réalise le meilleur temps et remporte l'étape devant son coéquipier Greg LEMOND. Production, producteur ou co-producteur : Antenne 2 Générique : Commentateurs : Robert Chapatte, Jacques Anquetil Tour de France 1986 Etape 13 Pau - Luchon Superbagnères Résumé - 16/07/1986 - 06'28"

Arrivée de la 13 ème étape du Tour de France 1986, une étape de montagne entre Pau et Superbagnères. L'Américain Greg LEMOND arrive détaché à Superbagnères et remporte sa première étape de montagne dans le Tour de France. Le Suisse Urs ZIMMERMANN et l'Ecossais Robert MILLAR arrivent à plus de une minute, suivis du Colombien Luis HERRERA, de l'Américain Andrew HAMSPTEN. Le maillot jaune Bernard HINAULT termine à plus de quatre minutes et conserve son maillot jaune avec moins d'une minute d'avance sur son coéquipier Greg LEMOND.

Production, producteur ou co-producteur : Antenne 2 Générique : Réalisateur : Pierre Badel Commentateurs : Robert Chapatte, Jacques Anquetil, Jean-Paul Ollivier

Tour de France 1986 Etape 16

Nîmes - Gap

Résumé - 19/07/1986 - 03'57"

Arrivée de la 16ème étape du Tour de France 1986, une étape de moyenne montagne de 246 km entre Nîmes et Gap. Le Jeune français Jean-François BERNARD arrive en solitaire à Gap et remporte sa première victoire d'étape dans le Tour de France. Production, producteur ou co-producteur : Antenne 2 Générique : Réalisateur : Pierre Badel Commentateurs : Robert Chapatte, Jacques Anquetil, Jean-Paul Ollivier

Tour de France 1986 Etape 18

Briançon - L'Alpe d'Huez

Résumé - 21/07/1986 - 01'53"

18 ème étape du Tour de France 1986, une étape de montagne de 182 km entre Briançon et l'Alpe-d'Huez. Ecrasante domination du maillot jaune Greg LEMOND et de son coéquipier Bernard HINAULT qui entament les dix derniers kilomètres d'ascension de l'Alpe-d'Huez avec plus de cinq minutes d'avance sur leur premier poursuivant, le Suisse Urs ZIMMERMANN.

Production, producteur ou co-producteur : Antenne 2 Générique : Réalisateurs : Pierre Badel, Jean-René Vivet Commentateurs : Robert Chapatte, Jacques Anquetil, Jean-Paul Ollivier

Résumé - 21/07/1986 - 03'50"

Arrivée de la 18 ème étape du Tour de France 1986, une étape de montagne entre Briançon et l'Alpe-d'Huez. Le maillot jaune Greg LEMOND et son coéquipier de l'équipe "La Vie Claire" Bernard HINAULT arrivent détachés au sommet de l'Alpe-d'Huez, avec plus de cinq minutes d'avance sur leurs poursuivants. Ils franchissent la ligne d'arrivée main dans la main. Bernard HINAULT remporte l'étape et Greg LEMOND consolide son maillot jaune.

Tour de France 1986 Etape 20

Contre-la-montre à Saint-Etienne

Le Journal du Tour - 24/07/1986 - 08'26"

Résumé de la 20 ème étape du Tour de France 1986, un contre-la-montre individuel de 58 km couru à Saint-Etienne et remporté par Bernard HINAULT devant son coéquipier Greg LEMOND, qui conserve son maillot jaune. Greg LEMOND au départ / Bernard Hinault - Caravane publicitaire / les derniers préparatifs du contre-la-montre. Coureurs interviewés rapidement sur le duel HINAULT-LEMOND. Coureurs en course : Julian GOROSPE, Jean Luc VANDENBROUCKE, Urs ZIMMERMANN - Chute de Stevens ROOKS dans un virage. Vélo aérodynamique de Bernard HINAULT équipé d'une roue spéciale / Alain DECROIX, mécanicien de Bernard Hinault - HINAULT enfourche son vélo / au départ - Greg LEMOND enfourche son vélo / au départ. HINAULT en plein effort / Lemond en plein effort - Chute de LEMOND dans un virage / il repart mais doit changer de vélo un peu plus loin. L'arrivée de Greg LEMOND - interview de Bernard HINAULT:"...le Tour est fini ; on ne s'attaque plus".

Production, producteur ou co-producteur : Antenne 2 Générique : journaliste : Alain Vernon

Tour de France 1986 Etape 21

Saint-Etienne - Puy-de-Dôme

Le Journal du Tour - 25/07/1986 - 07'40"

Résumé de la 21 ème étape du Tour de France 1986 courue entre Saint-Etienne et le sommet du Puy-de-Dôme avec la participation de Valery GISCARD D'ESTAING et Michel ROCARD, et interviews de ces derniers ainsi que de quelques coureurs et de leurs directeurs sportifs. L'étape est remportée par le suisse Erich MAECHLER.

Production, producteur ou co-producteur : Antenne 2

© Société du Tour de France

© ledicodutour.com

© Le Miroir des Sports

© AFP / Lionel Bonaventure

© Miroir du Cyclisme

© Courtesy Graziano Nardini www.dewielersite.net

© www.ledicodutour.com

© Miroir Sprint

Moment of truth – The Puy de Dôme and the Tour de France’s greatest duel

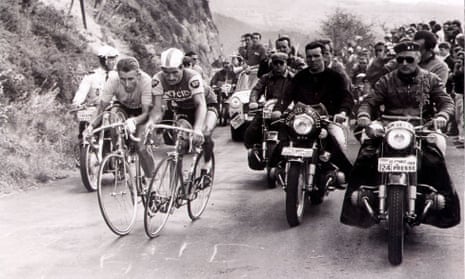

Jacques Anquetil and Raymond Poulidor go elbow to elbow in 1964

In Paris in the summer of 2001, the Luxembourg Gardens served as the site of an exhibition showcasing the greatest sports photographs of the 20th century. 100 images were displayed along its green railings, from fencing to football, from Alain Prost to Zinedine Zidane, but one picture drew more footfall than any other: Jacques Anquetil and Raymond Poulidor, elbow to elbow on the Puy de Dôme, locked in combat for the 1964 Tour de France.

Each evening, the pavement around the perimeter of the gardens was blocked by the masses who found themselves inexorably drawn to the image, pausing to gaze at the two figures in hushed silence as though contemplating a religious icon. In some ways, perhaps they were.

The photograph has a prose counterpart in the oft-cited words of race director Jacques Goddet after he had observed the contest at close quarters: “Their breath, their sweat, and the wool of their jerseys mixed.”

Much in like epic poetry, hand-to-hand combat has provided much of the most enduring passages from Tour history, and Anquetil and Poulidor’s contest outshone all others, reaching its apotheosis in the most striking way imaginable, on the extinct volcano of the Puy de Dôme just two days from Paris.

Over the years, it became an article of faith that Anquetil versus Poulidor was the Tour’s perfect duel and 1964 the race’s greatest edition. In 2004, a panel led by former Tour director Xavier Louy deemed it to be just that, and no other edition of the race has inspired quite the same mountain of prose as Anquetil’s fifth overall victory (or, depending on your point of view, as Poulidor’s most famous defeat). Barely a summer goes by without a new addition to an already extensive library. For so many French authors, writing of Anquetil and Poulidor mirrors how their counterparts across the Atlantic tackle Ali or DiMaggio. They are rarely writing about sportsmen so much as about a country and a place in time.

In 1964, France was a whole divided in two parts, one of which was occupied by anquetilistes and the other by poulidoristes . Their divergence in style and reputation of their two idols was mirrored in the clash between their nicknames. In one corner, the hauteur of ‘Maître Jacques.’ In the other, the more everyman charms of ‘Poupou.’

Get The Leadout Newsletter

The latest race content, interviews, features, reviews and expert buying guides, direct to your inbox!

Both were of farming stock, but it was the differences between them that always stood out: Anquetil was slender, blonde and reserved, Poulidor robust, dark-haired and affable. Anquetil’s Saint-Raphael team was managed by the era’s innovator, Raphael Geminiani. Poulidor served under the more traditionalist Antonin Magne at Mercier. Anquetil was a serial winner, winning the first of nine Grand Prix des Nations at 19 and landing his first Tour as a 23-year-old debutant in 1957. Poulidor would retire as ‘The Eternal Second’ after placing on the Tour podium no fewer than eight times.

Inevitably, the two rivals came to serve as symbols of their times. “Politically, and without it being necessarily rational, Anquetil was the incarnation of the realist and triumphant right,” the Jacques Augendre wrote in Anquetil-Poulidor, Un Divorce Français. “Poulidor reflected the left, more popular but less successful.”

Almost six decades on, Anquetil and Poulidor’s respective legacies are long since set in stone, frozen in time like the image atop this page. In the summer of 1964, however, Poulidor, two years Anquetil’s junior, was riding only his third Tour de France , and the cement on his reputation as the great nearly man of cycling hadn’t even begun to harden into fact.

Although Poulidor had taken a sound beating at Anquetil’s hand in the 1962 Tour, most notably he was caught and passed in the Lyon time trial, his star was still on the rise when he arrived in Rennes for the Grand Départ two years later. That spring, after all, he had taken victory at the Vuelta a España.

Anquetil, on the other hand, had already won a record four Tours, and in June 1964, he had claimed his second Giro d’Italia. Now he was seeking to emulate Fausto Coppi by becoming only the second man to pull of the Giro-Tour double, but his exertions in Italy had left him in a rather more vulnerable state that he would care to admit in July.

In hindsight, the 1964 Tour would mark something of a turning point in the history of the race, arriving at the very tail-end of the sepia-tinted ‘golden age’ of the post-war years. In that era, news of the action was relayed primarily by newspapermen and radio commentators. Even though limited live television coverage had been rolled out by 1964, for most of France, the Tour was still an event more imagined than witnessed.

Therein, perhaps, lies some of the enduring appeal of the 1964 Tour. The defining duel was already compelling, and the margins were remarkably tight, but the epic dimensions of the race were still permitted to take root in the mind rather than find themselves cut down to size by the tyranny of hours upon hours of television coverage.

Poulidor’s existence as the sine qua non of star-crossed Tour contenders began in earnest on stage 9 to Monaco where he made the error of sprinting for victory a lap too early, only for Anquetil on the final circuit of the track to claim the stage win and, with it, a one-minute time bonus.

Anquetil, the epitome of consistency, proceeded to win the time trial two days later, while reputation as a bon vivant and penchant for superstition came to the fore when the race broke for its rest day in Andorra. At the suggestion of Geminiani, Anquetil eschewed a rest day ride and attended a méchoui organised by Radio Andorra, posing for a photograph with an enormous leg of lamb and a glass of wine.

That decision looked to come back to haunt Anquetil when he was distanced on the opening climb of the Envalira the following morning, while popular legend insists that his initial reticence on the descent was triggered by the prediction of a ‘seer’ named Belline that he would die in a fall on the stage. Aided by some choice words from Geminiani, however, Anquetil spluttered back into action on the descent, swooping down the other side to save his Tour challenge.

By day’s end, Anquetil would even have gained 2:36 on Poulidor, who suffered a disaster in two acts in the finale of the stage, first by breaking a spoke and then crashing immediately after changing the wheel. Still, a solo victory at Luchon the next day brought him back to within just nine seconds of Anquetil, but there was still more misfortune to follow. In the Bayonne time trial on stage 17, Poulidor suffered a puncture and then endured a comedy of errors during his bike change.

And yet Poulidor still did more than enough to keep himself in the hunt. Even with the mishaps, he somehow limited his losses on the stage to a mere 37 seconds leaving him just 56 seconds behind an apparently flagging Anquetil in the overall standings. Despite his spate of misfortune, Poulidor increasingly gave the impression of being the stronger man and, two days from Paris, he had a shot at victory on what effectively amounted to home ground – the Puy de Dôme.

Stage 20 of the 1964 Tour was some 237km in length, but in reality, the day was mainly a long preamble towards the moment of truth awaiting the two protagonists atop the dormant volcano brooding over Clermont-Ferrand. The wait for the duel to commence only heightened the anticipation.

The Puy de Dôme is a short climb, just 6km in length , but the sheer relentless of its gradients means that time seems to slow down on that narrow and wickedly steep road. “The last kilometres seem to last as long as the whole stage,” Goddet wrote afterwards.

Time was of the essence for both men, with another time trial to come in Paris on the final day, and most observers reckoned that Poulidor needed at least half a minute or so over Anquetil ahead of that 27km test. In reality, maybe there was no need to overthink it: the jersey was the thing. If Poulidor managed to wrest the maillot jaune from Anquetil by any margin, the Tour was his to lose.

Such were the stakes when the climb began, with Anquetil and Poulidor immediately to the fore in a front group that also featured Julio Jimenez and Federico Bahamontes. The rest of the group began to melt away once Jimenez and Bahamontes began trading accelerations on the lower ramps of the ascent, and the Spanish duo would eventually forge clear. 3.5km from the summit, Anquetil and Poulidor were finally alone together.

Rather than defend himself by sitting on Poulidor’s wheel, as one would expect in modern cycling, Anquetil opted to place himself to his rival’s right-hand side. He was following the advice of Geminiani, who maintained that the psychological ploy was of greater benefit to Anquetil than the shelter of Poulidor’s wheel, and they would remain locked in those positions for more than two kilometres, pedalling side by side as they battled grimly against the gradient.

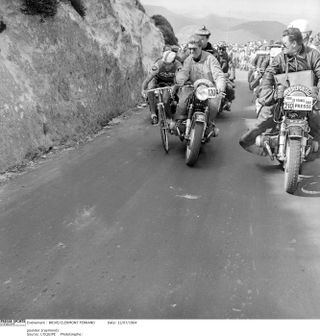

The crowds grew deeper as the climb drew on, while a flotilla of press motorbikes stalked them all the way, but each man seemed oblivious to everything but the ten metres of road in front of him and the rival at his elbow. 1,500m from the top, those elbows briefly came into contact, but still Anquetil and Poulidor stared ahead, as though each man believed acknowledging the other’s presence to be tantamount to a concession of defeat.

Shortly afterwards, however, Anquetil began to betray his first obvious signs of discomfort, as they approached the final kilometre, Poulidor began to ready himself for the attack. Poulidor’s acceleration finally came 900m from the top, and Anquetil could resist only for 50m or so before sitting heavily into his saddle and letting his rival go.

Anquetil’s pedalling slowed as he slumped over his handlebars during a final kilometre that seemed to last an eternity. Poulidor inched his way out of view, roared on by the multitudes who lined the upper reaches of the mountain. Anquetil, slowing further, was caught and passed by Vittorio Adorni. Poulidor crossed the line third on the stage, and then waited for the verdict of the mountain.

Some 42 seconds passed by the time Anquetil all but slumped across the line, his haunted eyes betraying the fact that he didn’t yet know his fate. When Geminani told Anquetil he had saved his maillot jaune by 14 seconds, his answer was succinct: “That’s 13 more than I needed.” The jersey was the thing.

The Tour was won. Even if the tightness of the margins and the extent of Anquetil’s collapse in the final 900m of Puy de Dôme gave some poulidoristes reason for hope in the final time trial, the man himself knew his chance had passed him by. “The Tour is over,” Poulidor said at the finish.

He was right. Anquetil, inevitably, sealed his fifth overall title in the concluding Bastille Day time trial, but the race of truth at this Tour had already taken place on Puy de Dôme. The tone of the post-mortem was set in the moments after Poulidor had finished, when three-time Tour winner Louison Bobet issued a gentle word of admonishment: “You went too late.”

Poulidor agreed, but only to a point. His attack came too late to win the Tour, true, but only because he wasn’t able to accelerate any sooner. “If I only dropped him 900m before the finish, it’s because I wasn’t able to do it before then,” he said later. “It’s easy to say I should have attacked earlier, but you don’t drop Anquetil just like that.”

That view was corroborated by Anquetil, who pointed out that both men were, by the time they reached Puy de Dôme, rinsed of all energy after a tumbling, spin cycle of a race where they had each flirted with disaster along the way. “The truth is that at Puy de Dôme, we didn’t see a great Poulidor or a great Anquetil,” he said. “The race had been very testing, physically and mentally. We were both tired.”

And yet, the idea took hold in the popular imagination that Poulidor had ultimately frittered away his chance of winning the Tour, spooked by Anquetil’s half-wheeling bluff. Poulidor, so that line of thinking went, had the legs to claim the yellow jersey that afternoon, only for Anquetil’s sangfroid to win the day.

Over the years, that notion has only heightened the mystique of that sweltering afternoon on the Puy de Dôme. It’s what draws people back again and again to look deep into that image for all the threads that made up the Tour’s greatest duel. Man against man. Man against mountain. Man against his own doubts. No wonder we can never look away.

What’s in a Cyclingnews subscription? We use our subscription fees to be able to keep producing all our usual great content as well as more premium pieces like this one. Find out more here

Barry Ryan is Head of Features at Cyclingnews. He has covered professional cycling since 2010, reporting from the Tour de France, Giro d’Italia and events from Argentina to Japan. His writing has appeared in The Independent, Procycling and Cycling Plus. He is the author of The Ascent: Sean Kelly, Stephen Roche and the Rise of Irish Cycling’s Golden Generation , published by Gill Books.

Cancellara’s Classics column: Attack might be Mathieu van der Poel’s best form of defence in chaotic Tour of Flanders

High stakes all around: Why the 2024 Itzulia Basque Country matters to Vingegaard, Roglic and Evenepoel

‘I don’t care’ – Julian Alaphilippe downplays impact of Patrick Lefevere criticism

Most Popular

By Kirsten Frattini March 25, 2024

By Fabian Cancellara March 25, 2024

By Barry Ryan March 23, 2024

By Fabian Cancellara March 23, 2024

By Kirsten Frattini March 23, 2024

By Alasdair Fotheringham March 23, 2024

By Paul Norman March 22, 2024

By Josh Ross March 21, 2024

By Barry Ryan, Alasdair Fotheringham March 20, 2024

By Barry Ryan March 19, 2024

By Dan Challis March 18, 2024

- off.road.cc

- Dealclincher

- Fantasy Cycling

Support road.cc

Like this site? Help us to make it better.

- Sportive and endurance bikes

- Gravel and adventure bikes

- Urban and hybrid bikes

- Touring bikes

- Cyclocross bikes

- Electric bikes

- Folding bikes

- Fixed & singlespeed bikes

- Children's bikes

- Time trial bikes

- Accessories - misc

- Computer mounts

- Bike bags & cases

- Bottle cages

- Child seats

- Lights - front

- Lights - rear

- Lights - sets

- Pumps & CO2 inflators

- Puncture kits

- Reflectives

- Smart watches

- Stands and racks

- Arm & leg warmers

- Base layers

- Gloves - full finger

- Gloves - mitts

- Jerseys - casual

- Jerseys - long sleeve

- Jerseys - short sleeve

- Shorts & 3/4s

- Tights & longs

- Bar tape & grips

- Bottom brackets

- Brake & gear cables

- Brake & STI levers

- Brake pads & spares

- Cassettes & freewheels

- Chainsets & chainrings

- Derailleurs - front

- Derailleurs - rear

- Gear levers & shifters

- Handlebars & extensions

- Inner tubes

- Quick releases & skewers

- Energy & recovery bars

- Energy & recovery drinks

- Energy & recovery gels

- Heart rate monitors

- Hydration products

- Hydration systems

- Indoor trainers

- Power measurement

- Skincare & embrocation

- Training - misc

- Cleaning products

- Lubrication

- Tools - multitools

- Tools - Portable

- Tools - workshop

- Books, Maps & DVDs

- Camping and outdoor equipment

- Gifts & misc

Tour de France legends: The iconic Puy de Dôme returns to the Tour after 35 years

One of cycling’s dormant legends, the Puy de Dôme, will explode back into life on stage nine of the 2023 Tour de France. But why does this mythical dome-shaped volcanic plug in the Massif Central hold such an important place in the Tour’s history, despite not being used for 35 years? And what does its return say about the race itself, and its constant and complex fascination with modernity and tradition, innovation and nostalgia?

Ask any pro cycling fan to name the most romantic, emblematic Tour de France climb, and you’ll get a dozen or so different answers and opinions. Most of which will be wrong.

It’s not Alpe d’Huez, the ‘Wembley of cycling’, a climb so gainfully employed by the Tour since the 1970s that it became almost too familiar, to the extent that race organisers ASO have reduced it to a freelance role in recent years. What about the doyennes of the Alps and Pyrenees, the Galibier and the Tourmalet? Nah. Mont Ventoux is certainly in with a shout, its occasional use and aura allowing it to retain an inherent sense of mystique and drama.

But for anyone in their 30s or younger, the Puy de Dôme – an asymmetric green lava dome that towers over Clermont Ferrand and the Auvergne in central France – represents a mothballed snapshot of a bygone era of professional cycling and the Tour de France, a romanticised moment (imagined or otherwise) of the sport captured in time, before EPO, Lance, and the Sky train.

(A.S.O./Morgan Bove)

The Puy is an atmospheric, evocative climb, unlike any other used by the Tour. Unlike the hairpin bends of the Alps, its road, which only replaced the original railway in 1926, spirals like a corkscrew around the mountain in one relentlessly steep gradient to the summit. There you’ll find the mountain’s emblematic observatory tower, a second-century temple, and stunning views of Clermont Ferrand and the Chaîne des Puys, a chain of cinder cones and lava domes stretching for 25 miles across the Massif Central.

Thanks to its central location and ability to shake up a race due to its fearsome gradients, the Puy de Dôme became a regular feature on the Tour route following its first inclusion in 1952. By the time of its until-now final appearance in 1988, it held the joint record – along with Alpe d’Huez – as the most often used summit finish in the Tour’s history, featuring 13 times.

Myth Making

During that period, it played host to some of the race’s most symbolic, transcendental events, from Fausto Coppi’s win on the climb’s debut in 1952 to Bernard Hinault’s first authoritative stamp on the Tour in 1978 (and, incidentally, the Badger’s final concession to teammate and heir apparent Greg LeMond in 1986).

The Puy was also the scene of the beginning of the end of one of cycling’s defining eras. In 1975, Eddy Merckx, aiming for his sixth Tour win and momentarily succeeding in keeping Lucien Van Impe and home favourite Bernard Thévenet within arm’s reach on the summit finish, was punched in the kidneys by spectator Nello Breton. Injured from the impact of Breton’s ‘accidental’ intervention, the Cannibal’s reign at the top of his sport would end in Pra-Loup two days later.

However, there is one day, and two racers, that encapsulate the Puy de Dôme’s lofty standing in the Tour’s mythology more than any others.

In 1964 Maître Jacques Anquetil was four Tours to the good, an imperious, undroppable, but not extremely popular presence at his home race. Meanwhile, the younger Raymond Poulidor, who finished third overall two years previously, had emerged as his closest rival for the yellow jersey, and the true owner of the French public’s affections.

By the final mountain stage of the 1964 race, to the summit of the Puy, the two Frenchman – representing to fans the polar extremes of a cyclist’s character: one a relentless winning machine, the other a charismatic underdog – were separated by only 56 seconds on the GC.

While Julio Jiménez and Federico Bahamontès tore off up the ever-steepening road to the top of the volcano, the stage win and mountain points in mind, Poulidor and Anquetil remained locked together behind, literally shoulder to shoulder, matching each other pedal stroke for pedal stroke.

Was Anquetil bluffing, riding alongside his rival in an attempt to conceal his discomfort and to dissuade the overly cautious Poulidor from attacking? We’ll never know, but when Poulidor finally unleashed his killer blow – within sight of the summit – he put 42 seconds into the battling, for once ragged Anquetil in under a kilometre.

Despite the pyrotechnics, it was all too little, too late: the defending champion remained in yellow – by 14 seconds. “That’s 13 more than I need,” he said at the finish. As Maître Jacques slumped exhausted onto the bonnet of his team manager’s car at the top of the volcano, the myth of Anquetil and Poulidor’s rivalry – and of the Puy de Dôme – was born.

However, all good things must come to an end, and for three and a half decades anyway, the relentless march of modernity, and practical necessity, superseded the Tour’s penchant for unabashed nostalgia.

By the late 1980s, the continued expansion of the Tour into a global behemoth, with its cavalcade of vehicles and infrastructure, had made hosting the race on the Puy de Dôme’s cramped summit a logistical nightmare, a difficulty only enhanced by the construction of a funicular railway to the summit in 2012, further shrinking the already narrow road and reducing its status as a cyclo-tourist destination to one predetermined day a year.

While it was still used by adventure races such as the Transcontinental, where it hosted the 2017 edition’s first checkpoints, the Puy’s days as a Tour summit finish were thought to be long gone.

Past and Present

View from the top (A.S.O./Morgan Bove)

However, as the volcano’s mythical status grew in the years since its last appearance in 1988, so too did the clamour for its return. According to Tour director Christian Prudhomme, bringing the Tour back to the Puy de Dôme was the first objective he set himself when he joined ASO back in 2004.

Successful experiments at smaller-scale summit finish operations, such as those on the Galibier and Tourmalet, as well as the Super Planche des Belles Filles, showed Prudhomme that his goal was at least possible, and whispers of a return to the Puy duly intensified by the early 2020s. Those rumours were finally confirmed last October, when the Tour director confirmed that, after 35 long years, the Puy de Dôme would host the summit finish of stage nine of the 2023 Tour.

While it’s all well and good waxing lyrical about mythical battles of a bygone era – a facet of the Tour’s identity at which Prudhomme has certainly excelled as director – what should we expect when it comes to the racing in 2023?

UAE Team Emirates tackle the Puy de Dôme during a pre-Tour recce (A.S.O./Morgan Bove)

Well, first of all, don’t be expecting Mathieu van der Poel to emulate his grandfather – whose hometown of Saint-Léonard- de-Noblat will incidentally host the stage start – on the volcano’s fearsome slopes (though you never know with the mercurial Alpecin-Deceuninck star).

Because the Puy de Dôme is a relentless monster of a climb.

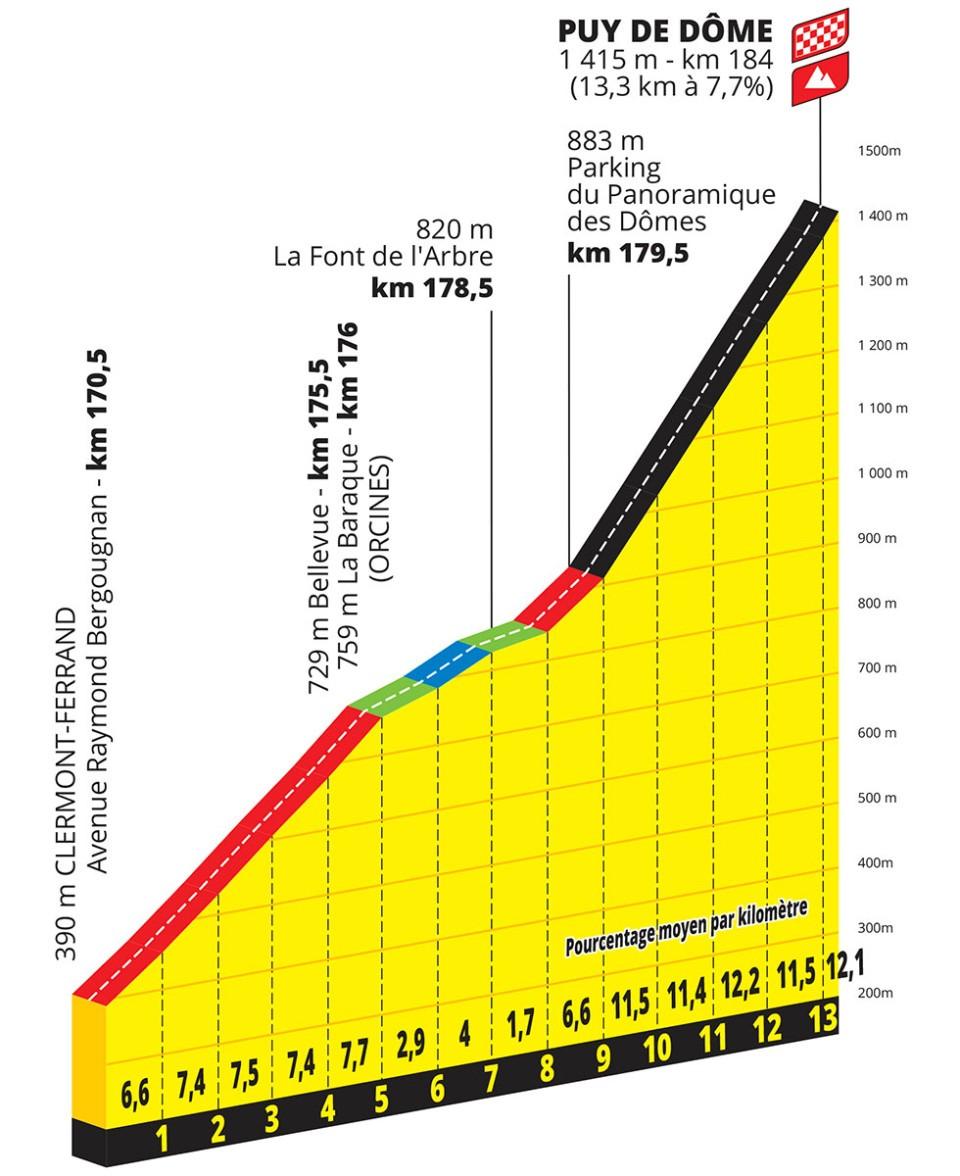

Rising sharply out of Clermont-Ferrand, the road then eases off for three kilometres of relative false flat before stage nine’s defining moment on the dome, where a still sizeable group could be spat out onto the extremely narrow and steep road to the summit – three riders wide, tops – and left to fend for themselves.

The final four kilometres are, it’s safe to say, savage. According to VeloViewer, the unrelenting gradient never dips below 11.5 percent, and touches 18 percent in the final 200m, with not a bend or hairpin in sight to ease the suffering.

Due to the narrowness of the road, and the mountain’s status as a UNESCO World Heritage Site, with its focus on preserving the local flora and fauna, no spectators will be allowed in the final four kilometres. The lack of fans (300,000 were estimated to be on the Puy to watch a time trial at the 1983 Tour) will do little to dampen the spectacle, however.

Egan Bernal tests his legs on the Puy earlier this year (A.S.O./Morgan Bove)

It may not be the longest climb, but it will certainly do some damage, and will likely favour a climber capable of withstanding steep gradients while retaining some sort of kick at the end. It seems tailor-made for Tadej Pogačar then, though perhaps local boy Romain Bardet could spring a surprise and take a popular home victory?

If Bardet, from nearby Brioude, is to triumph on the Puy, he’ll have to channel the spirit of the ancient Averni, who defeated the Roman Republican army led by Julius Caesar at the Battle of Gergovia, held in the shadow of the Puy de Dôme, in 52BC.

Despite the Averni’s victory – forged on the basis of an intelligent counterattack (take note Romain) – the Romans’ overwhelming strength ensured that they ultimately prevailed in the region, a fate that may await any GC contender foolish enough to attempt to unsettle the might of Jumbo-Visma and UAE Team Emirates on the Puy.

“It’s a different climb to those we usually tackle,” Bardet said before the Tour. “The road surface is perfect and winds around the mountain at a steep but steady gradient. I won’t be at all surprised to see the future Tour de France winner prevail at the top of the Puy de Dôme.”

Will 2022 Tour winner Jonas Vingegaard still be up for sampling the view after stage nine? (A.S.O./Morgan Bove)

In any case, whoever makes it to the top first may be inclined to offer up a prayer at the Temple of Mercury, a second-century place of worship which lay undiscovered for centuries, until it was unearthed during the construction of the mountain’s first observatory in the 1870s.

Just like that nineteenth-century discovery, the unearthing of the Puy de Dôme as an iconic Tour de France venue on Sunday will once again underline both the mountain and the race’s ever-evolving, ever-complex relationship with tradition and innovation, and its storied past and exciting present.

And the peloton of 2023 will finally – after 35 long years – be able to add another layer to the story of the Puy de Dôme.

Help us to fund our site

We’ve noticed you’re using an ad blocker. If you like road.cc, but you don’t like ads, please consider subscribing to the site to support us directly. As a subscriber you can read road.cc ad-free, from as little as £1.99.

If you don’t want to subscribe, please turn your ad blocker off. The revenue from adverts helps to fund our site.

Help us to bring you the best cycling content

If you’ve enjoyed this article, then please consider subscribing to road.cc from as little as £1.99. Our mission is to bring you all the news that’s relevant to you as a cyclist, independent reviews, impartial buying advice and more. Your subscription will help us to do more.

Ryan joined road.cc in December 2021 and since then has kept the site’s readers and listeners informed and enthralled (well at least occasionally) on news, the live blog, and the road.cc Podcast. After boarding a wrong bus at the world championships and ruining a good pair of jeans at the cyclocross, he now serves as road.cc’s senior news writer. Before his foray into cycling journalism, he wallowed in the equally pitiless world of academia, where he wrote a book about Victorian politics and droned on about cycling and bikes to classes of bored students (while taking every chance he could get to talk about cycling in print or on the radio). He can be found riding his bike very slowly around the narrow, scenic country lanes of Co. Down.

Add new comment

- Log in or register to post comments

Latest Comments

What fresh hell is this invading my Facebook feed? Where do those wires lead back to?

Carpet pedals? You're two days early. DId you think it was April 1st already?

For me one of the benefits of SRAM AXS is no cables, I wouldn't want to add them back in to charge the batteries. I haven't had a problem with a...

Although not necessarily children, it still amazes me how many competitive riders are surprised when commissaires refuse to let them start races...

Grig Wrong.

I have dozens of black friends and not one of them has ever experienced racism, it's just made up by people who "wake up every morning determined...

Pictures sent to the Gazette show a grey car has crashed near Silky Traditional Turkish Barbers and Rose Kebab House, in Barrack Street, Colchester...

They are just a troll and I doubt anything they say. They have a history of describing 99% of cyclists as stupid, reckless, having no brains etc...

I dunno about that (and in the Welsh Water case as Rich_cb notes the holding company has no shareholders). But I'm definitely a customer. And if...

Great article. Very informative. Certainly allays almost all of the concerns I had about electronic groupsets, particularly the range/charge status...

- International edition

- Australia edition

- Europe edition

Tour de France returns to storied climb of Le Puy de Dôme after 35 years

There are longer ascents but few that match the gruelling drama or history of the extinct volcano in the Massif Central

I n the pantheon of the Tour de France’s most storied climbs, Sunday’s stage finish at Le Puy de Dôme stands apart for one reason: for 35 years it looked set to remain lost permanently in the mists of Tour history, the climb that would never be repeated.

It became a staple question when interviewing the Tour de France director, Christian Prudhomme: would the race return to the extinct volcano in the Massif Central? Prudhomme would always give a version of the same answer. When he had begun work at the Tour owners, ASO, in 2004, taking the race back to the Puy had been top of the to-do list on his computer, and it would happen when local politics permitted.

Compared with other ascents tackled by the Tour, the Puy de Dôme is not the longest, the highest nor the steepest. It tops out at a relatively modest (for the Tour) 1,415m and the toughest, final section lasts a mere 4km, with a stiffest gradient of about 14%. But the first winner on the summit, Fausto Coppi, said it was “harder than Mont Ventoux” and the man who took the Tour up there for the first time in 1952, Jacques Goddet, described it as “literally a backbreaker”.

What sets the Puy apart is the unremitting nature of the gradient, averaging 12% after the barrier at the foot of the climb with 4.2km to the top, unbroken by a single hairpin as the road spirals round the extinct volcano “like a helter‑skelter in reverse”, according to Geoffrey Nicholson.

Prudhomme, after confirming the climb would return this year, said: “This is what is unique. It’s not just the steepness but the fact the road turns in the same direction. That doesn’t happen anywhere else, it’s what has made this climb mythical.”

Like Ventoux, the almost perfectly conical Pûy can be seen looming threateningly from many miles away, but unlike the Giant of Provence it is covered in lush vegetation and more significantly it is a dead-end road. The Tour was drawn here, Nicholson wrote, because it was a climb of great severity, with a city (Clermont-Ferrand) nearby and a toll gate at its foot. In contrast to every other ascent on the Tour, spectators could be charged for entry.

As ever with the Tour’s great ascents, it’s not just about the toughness, but the history. The climb’s significance is summed up in one image: the two great rivals of the 1960s, Jacques Anquetil and Raymond Poulidor, shoulder to shoulder near the top of the ascent on 12 July 1964, the crowning moment of French bike racing’s defining rivalry.

The memories have now faded, but Poulidor’s enduring popularity could still be seen half a century later at the Tour when he turned up each day to milk the applause; Sunday’s stage starts at his home town of Saint-Léonard-de-Noblat in tribute to him. The duel on the slopes of the mountain that day, in front of a crowd well into six figures, saw Anquetil pushed to the limit before he finally cracked. Poulidor gained enough time to hope for the overall win but, in keeping with a career where hope was usually trumped by reality, not quite enough to take the yellow jersey.

The list of winners on the Pûy includes such illustrious names as Felice Gimondi, Federico Bahamontes, Luis Ocaña and Lucien Van Impe, but it has also created one glorious anticlimax: the finish in 1969, when Eddy Merckx was preceded to the top by the lanterne rouge Pierre Matignon, who took full advantage of a long-distance break. Something similar happened in 1988 when the Danish journeyman Johnny Weltz was the winner.

Merckx has bitter memories of the place, as in 1975 he was punched in the kidneys by one of the crowd 200m from the finish. Merckx crossed the line and rode back to identify his attacker, Nello Breton, whom he took to court for a symbolic one franc in damages.

after newsletter promotion

Since Weltz’s win, a combination of factors have kept the Tour from the mountain. Initially, it was because the Tour caravan had grown to the extent that there was no space at the top of the one-way road to accommodate the many pantechnicons. Under Prudhomme the Tour has learned to adapt to ever-tighter finishes, but then local politics came into play.

The regional president was keen for the top of the extinct volcano to be defined as a Unesco reserve, which meant keeping the Tour out, while the construction of a narrow-gauge railway up the road to the top meant there would be barely enough space for the riders, let alone spectators. Barriers were put up at the start of the steepest section, where even leisure cycling is banned. The top of the climb will be closed to the fans, who will be encouraged to watch the race on the lower slopes where the route climbs out of Clermont-Ferrand.

Fans or no fans, the Tour is back, and 59 years after Anquetil and Poulidor, the 2023 Tour’s first eight days have been marked by another one-on-one duel: Tadej Pogacar and Jonas Vingegaard, who have torn chunks out of each other in the Basque Country, on the Col du Marie Blanque, and the Cauterets climb.

Round four between the Slovenian and the Dane is set for the slopes of a mountain that has at various times been sacred to the Gauls, the Romans – who built a temple of Mercury on the summit – and the Christians, and which is now about to regain its iconic status in cycling at last.

- Tour de France 2023

- The Observer

- Tour de France

Most viewed

- Tour de France

- Giro d'Italia

- La Vuelta ciclista a España

- World Championships

- Amstel Gold Race

- Milano-Sanremo

- Tirreno-Adriatico

- Liège-Bastogne-Liège

- Il Lombardia

- La Flèche Wallonne

- Paris - Nice

- Paris-Roubaix

- Volta Ciclista a Catalunya

- Critérium du Dauphiné

- Tour des Flandres

- Gent-Wevelgem in Flanders Fields

- Clásica Ciclista San Sebastián

- INEOS Grenadiers

- Groupama - FDJ

- EF Education-EasyPost

- Decathlon AG2R La Mondiale Team

- BORA - hansgrohe

- Bahrain - Victorious

- Astana Qazaqstan Team

- Intermarché - Wanty

- Lidl - Trek

- Movistar Team

- Soudal - Quick Step

- Team dsm-firmenich PostNL

- Team Jayco AlUla

- Team Visma | Lease a Bike

- UAE Team Emirates

- Arkéa - B&B Hotels

- Alpecin-Deceuninck

- Grand tours

- Countdown to 3 billion pageviews

- Favorite500

- Profile Score

- Stage 23 Results

- Top competitors

- Startlist quality

- All stage profiles

- Hardest stages

- Winners and leaders

- Prizemoney ranking

- Fastest stages

- Statistics - Statistics

- Startlist - Startlist

- More - More

- Teams - Teams

- Nations - Nations

- Route - Route